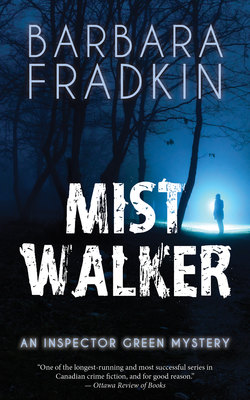

Читать книгу Mist Walker - Barbara Fradkin - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Two

ОглавлениеEven before Green set foot in his hot, airless kitchen, he extended a silver gift bag through the archway and slipped it onto the kitchen table. Sharon was on her hands and knees beneath the high chair, rescuing Tony’s hamburger, and she peered up at him through damp locks of black hair. Her gaze was frosty. Propped in his high chair, the toddler wiggled with delight at the sight of his father and shouted to be picked up. Sharon’s frown dissolved into a smile as she pulled the gift bag towards her.

“Offerings to the gods, Green?” She peeked inside, then extracted a tub of Ben and Jerry’s New York Super Fudge Chunk ice cream. Her smile widened. She rose, slipped her arms around his neck and kissed him. “The gods are pleased.”

He lingered over the kiss, savouring the pressure of her soft, petite body against his. “Sorry I’m late.”

She extricated herself to put the ice cream away while he scooped his son into his arms. “So what was Mary Sullivan’s latest catastrophe like, anyway?” she asked.

He hesitated. How to describe the house he’d just seen, with its broad veranda, steeply pitched roof and trademark Ottawa red brick? How to capture its promise and keep Sharon’s mind open? Tony was squirming, Sharon was frazzled, and with the air conditioner on the blink, their new house was a sweltering 28˚C. Such a description was best left until after Tony’s bedtime, when Sharon had her feet up and a glass of wine in her hand.

“Oh...interesting,” he replied as he set Tony down and cracked open an ice cold coke from the fridge.

“Interesting good or interesting bad?”

“Both. But we can talk about it later.”

Tony had pulled open a bottom cupboard and was happily banging pots together. Ignoring the racket, Sharon snatched Green’s coke to take a long swig. “Both. That sounds ominous.”

Green took another coke from the fridge and rolled the cold can across his brow. The sodden summer heat hung in the air, and although Sharon had opened the windows as far as she could, in the treeless pasture where they lived, the sun beat down all day, and the air barely stirred. He thought of the house he’d just seen in Highland Park, so overgrown with brush that it barely saw the light of day. What a welcome thought.

“Not ominous. It just...needs work.”

“Uh-oh.” She eyed him warily. “I sense slanting floors and a ventilated roof. Green, I’m not moving into a place with kerosene lamps and an outhouse.”

“Oh, I think there’s electricity. Maybe a few other surprises—”

“Green!” she protested, obviously too hot for humour. She dove to rescue a glass bowl from her son’s grasp. He began to shout, and barely missing a beat, she gave him a pot and wooden spoon. “God, Mary’s having a field day with you!”

He laughed. “Speaking of surprises, someone who knows you came to my office today. Another reason I was late. A woman named Janice Tanner, a patient at Rideau Psychiatric.”

Sharon looked blank, so he supplied another clue. “She’s in an agoraphobic therapy group.”

“Oh, that’s Outpatients. But the name’s familiar.” Sharon took a deep swig of cola and closed her eyes gratefully. “Janice Tanner. About forty? Tall, thin, nervous-looking? Short, greying hair and glasses?”

He shook his head and raised his voice over the banging spoon. “Tall and thin, yes, but she has red hair and no glasses.”

“Then she’s fixed herself up somewhat since I knew her. I think she was an inpatient on my ward a couple of years ago, admitted because she was too terrified to leave her apartment, and she was slowly starving to death.”

“Could be her.”

“I’d say she’s come a long way if she made it all the way to your office on her own. Either that or she’s desperate.”

“A bit of both, I think. She was certainly persistent. Insisted one of the other phobic patients had met with some serious harm. Was she the type to overreact?”

“A phobic overreact? Unheard of.” She sobered as she watched Tony, tiring of his spoon, run out into the hallway. “You put the gate up, eh? No, Janice was a shut-in, and she’d had very little contact with people for years. I remember nobody ever came to visit her in hospital. But she did have a good heart, and after she’d settled in, she took a couple of our more fragile schizs under her wing.”

Not necessarily a good sign, Green thought, and voiced his misgivings. “Did she have a preference for fragile schizs? I mean, was she drawn to weirdos?”

“Not weird for weird’s sake, but I think she felt more comfortable with people who needed her. Why? Who was the patient she’s worried about? Maybe I know her.”

“Him. Matt Fraser.”

Sharon’s eyebrows shot up. “A ‘him’? My, Janice really has made progress. I don’t know him, though.”

“Who would know him at the hospital?”

“The therapist who runs that group, and I have no idea who that is. And his treating psychiatrist.” She smiled slowly. “Mike, you didn’t promise her you’d look into it.”

“No, I didn’t. You’d be proud of me, I didn’t promise a thing. Well... maybe that I’d check with the officer on the missing persons file. But the case has a curious feel. I don’t know what it is.”

“The fabled Inspector Green intuition?”

“Something like that. Could you maybe, subtly, ask around about this guy? Find out if he’s missed any appointments or left word about his plans?”

She paused with her coke can to her lips. “Subtly?”

“Okay, forget subtle. Find out who his therapist is. Find out what kind of guy this Matt Fraser is.”

She raised one eyebrow slowly in silent rebuke that he would ask her to violate patient confidentiality. He raised his palms in a classic Yiddish shrug which said it was the furthest thing from his mind. Both of them dealt with confidential material all the time, and he knew no further words were necessary. She would make casual inquiries about Matt Fraser at the hospital, and if, in her judgment, anything suspicious or worrisome emerged, she would quietly pass it on to him.

In the meantime, because curiosity had always been one of his greatest failings as well as his greatest asset, he decided that when he got bored in the morning, he would pull the police file on Matt Fraser and see what he could learn.

* * *

The file on Fraser’s old case proved to be voluminous, suggesting that although the man had only had one criminal charge, it had been a complicated one. It was all on microfiche in the records department, and over the phone, the records clerk implied that Green shouldn’t hold his breath waiting for her to print it out.

After he’d hung up, Green eyed the clutter on his desk and the list of unread emails stacked up in his electronic inbox. A rooming house fire in Vanier during the night had claimed at least one life and drawn a team of Ident officers and Major Crimes detectives out to the scene, including Brian Sullivan. The Staff Sergeant in Youth wanted a meeting to discuss the rise of swarmings in Ottawa’s south end, and Superintendent Adam Jules had asked him to review the agenda for yet another meeting. The last thing Green needed was fifty pounds of microfiche print-outs dumped on his desk as well.

He drummed his fingers on his desk as he considered other approaches. Barbara Devine had been the lead investigator on the Fraser case. Plain Detective Devine back then, Inspector now. After her stint in sex crimes, she’d made the rounds through the departments on her way up the ladder and was now ensconced in an office one floor closer to the gods than his, pushing paper and keeping company with the senior brass. Backroom gossip held that she’d once been an idealistic, hardhitting detective who’d soured on the nobility and purpose of what she was doing and turned her attentions instead to the cause of her own advancement. Although he’d never worked directly with her, she was a contemporary of Green’s with a string of relationship disasters that eclipsed his own. Currently, having burned her way through three husbands, she’d set her sights on Superintendent Adam Jules, the austere and resolutely celibate chief of CID . The thought made Green’s lips twitch irrepressibly.

Counting on the lure of an old case to draw her into his quest, he grabbed his notebook and headed up the stairs to her office. Devine owned an array of power suits from Holt Renfrew, and today she had packaged herself in dark red with fingernails and lips to match. The door to her spotless office was ajar, and he could see her typing furiously away at her computer. She scowled at him dubiously as he strode in. Probably afraid I’ll want her to do some actual police work, he thought and cut off any incipient protest by dropping into a chair and tossing his notebook on her desk.

“Barbara, I need to pick your considerable brain. Remember Matthew Fraser?”

She sat back, her fingers still poised over the keyboard and her eyes slitting warily. “Certainly. One of the most frustrating and disappointing cases I’ve ever worked. Why do you ask?”

“His name’s come up. Tell me about the case.”

“What’s he done? Offended again?”

“No, he’s been reported missing.”

“In that case, good riddance,” she said, brushing nonexistent dust from her desk and straightening a stack of reports. “I wouldn’t waste too much energy on it.”

He grinned and propped his feet on the edge of her pristine desk. “That’s why I’m here. The file is going to be several truck loads, so I’m looking for an executive summary before I put any manpower on it.”

She eyed his feet in silence for a moment, her red nails tapping the desktop, and he could almost see her weighing how much to cooperate. “You must remember the case, Mike,” she said eventually. “Two of our officers quit the force after the trial. They had little children themselves, and they couldn’t stomach working for a system that gives the villains all the breaks.”

Finally the penny dropped. Matthew Fraser had been an elementary school teacher accused and ultimately acquitted of sexual abuse, and Green could still recall the bitter divisions the case had engendered not only within the school and community but within CID itself.

“Did you think he was guilty?” he asked.

Her eyes flashed and her mouth grew hard, but she restrained herself. “I’d never have brought the case forward if I’d doubted that. I was the one who took the girl’s initial statement. I watched her face that first time in the station, I heard her crying and saying ‘I just want him to stop.’ She was very credible before the lawyers and the Children’s Aid got into the act, and the whole courtroom circus froze her up.”

“So she recanted on the witness stand?”

Devine shook her head vigorously. “If I had dropped all the cases where the abuse victims had second thoughts, I’d have had precious little work to do. But Rebecca Whelan didn’t really recant. She just got confused, the defence chipped away at her recollections, and the judge was ‘See no evil, hear no evil’ Maloney, who wouldn’t recognize sexual abuse if it was—” She pressed her lips together as if to prevent further indiscretions from escaping.

“Shoved up his ass?” Green said. “Was there any other evidence? Any other complainants?”

“You’re not the only one on the force who knows how to build a case, Mike. We had plenty of circumstantial evidence. I had doctors and abuse experts who swore she had all the classic signs, I had other little girls who alleged touching or grooming types of activity, but it was either too vague or the parents wouldn’t let them testify. So in the end, what it boiled down to was this six-year-old all alone in the courtroom, sitting on a telephone book so she could see over the witness box, with the judge staring down at her and the high-priced lawyer from the teacher’s union hammering away at her every word. She crumbled.”

Green made a face, inwardly grateful that he had resisted the pressure to do his turn in sex crimes. Adults killing each other were bad enough. “What was Matthew Fraser like?”

“He was one sick bastard,” she replied, her discretion lost in the heat of her recollections. Her lips formed a harsh red slash of emotion across her carefully made up face. “One of those quiet, unreadable types. You know, the type who plots murder without ever changing his expression. He acted so concerned for the little girl, but he put her through six weeks of active trial while he paraded all his teacher friends across the stand one after another to say what a great guy he was. Of course, I hear they all dropped him like a hot potato afterwards. For the cameras it was union solidarity rah, rah, and all that, but out of the public view, that was another story.”

“He apparently told a friend he was being followed recently. Any threats on his life after he was acquitted? I imagine there were people in the girl’s family who would have liked to see him suffer.”

“And half a dozen guys on the force eager to do the job for them,” she countered. “But it’s been ten years, Mike. That’s not exactly heat of the moment.”

Ten years is nothing in the life sentence of the victim’s family, he thought. Or of the little girl herself, who would be almost seventeen by now. “Do you know what happened to the girl?”

Devine’s face darkened abruptly, further marring her studied Holt Renfrew finish. “That man put her through hell. The doctor said the abuse had happened repeatedly, but the bastard pleaded not guilty, virtually accused the girl of lying, and then dragged the case through the system for over two years. Two years of motions and postponements on every technicality in the book, two years that little girl had to hang in limbo, with everybody whispering about her. She had to change schools and move to a new neighbourhood, so she lost all her old friends. I did my best, but...” She threw up her hands. “Damn, it still gets to me!”

Her passion and moral outrage surprised him—even attracted him—and she moved up a few notches in his esteem. “Yeah, you do this job long enough, and there are always a few that stick with you. But think of it this way, Barbara, if it still gets your blood boiling after ten years, how does the family feel?”

Her anger cleared as she weighed his question. “They hate him. That will always be there. But I think you should be looking for more recent victims. Believe me, men like Fraser don’t stop once they get a taste.”

He shrugged easily. “I’m just exploring ideas here, Barbara, not putting anyone on trial. What was the family like?”

She played with her left earring as she considered his question. “Her family was right in the thick of things, but they were basically good people. Mother, father, stepfather. Even her grandparents showed up for the verdict.”

“Any worrisome signs?”

“Nothing you wouldn’t expect. I mean, a lot of people despised the man. Even some of the other parents, who were afraid he might have abused their children too. Fraser had a classic pedophile profile, Mike. Soft-spoken, shy, liked to hang around with children, and he had this gentle manner that hooked them right in. Children couldn’t see the manipulation behind his overtures, so I couldn’t get anything more solid than a twisted feeling in my gut. Who knows, maybe if I had, the guy would have been put away where he belongs, instead of out roaming the streets, where he’s probably raped three dozen other little girls in the time since.”

* * *

That unsettling thought stayed with Green after he returned to his office. It lent a greater urgency to the mysterious disappearance than did a ten-year-old settling of accounts. Perhaps there was a more recent score to settle, or a more recent danger to flee. Shortly after eleven, telling himself he’d earned a decent lunch break after weeks of car seat dining, he headed out.

For a man who lived in fear, Matt Fraser had chosen to reside in an unsavoury part of town. Built upon the vacant lumber yards of J.R.Booth’s old empire, Carlington had once been a modest, house-proud working-class neighbourhood first settled by World War II vets returning to civilian life. It was now a hodge-podge of post-war shanties, welfare townhouses and massive high-rises, a neighbourhood where new refugee families were sandwiched in with drug dealers, blue collar retirees and the working poor. Petty crime flourished, and bands of youth prowled the streets with restless contempt. Green suspected that poverty, not preference, had dictated Fraser’s choice.

Fraser’s apartment was on the third floor of a squat brick low-rise, surrounded by decrepit parking lots. Weeds sprouted through the broken asphalt, and against one wall were the rusted shells of two cars. The apartment’s security was a paranoid’s nightmare—a row of buzzers just inside the front door, which had been propped open with a stick to encourage some flow of muggy air. Inside, the odour of onions mingled with a stench of rot in the fetid air. After much knocking, Green roused the building super from his midday siesta in his basement apartment. The TV was blaring, and the man opened the door wearing nothing but a scowl and rumpled boxers hitched high over his sagging gut. But one flash of Green’s badge sent him shuffling back inside for a pair of overalls and a set of keys to Matt Fraser’s apartment.

“Nice guy,” the super observed two minutes later as he laboured up the narrow staircase. “Wish all the tenants were as good as him.”

Green peered at him through the gloom. New light bulbs were evidently not part of the landlord’s budget. “What do you mean?”

“No noise, no late-night visitors, fixes everything hisself. Won’t even let me in to do the repairs. Even the dog’s quiet. Big bugger, and quite a few people are scared of it, but it wouldn’t hurt a flea.”

“Does he get many visitors?”

“None that I seen. Sticks to hisself. Why, what’s he done?”

“He’s missing. When did you last see him?”

The man grunted at each step with the effort of lifting his bulk. “Not in a few days. But he’s usually out really early walking his dog, then again late at night. You think something’s happened to him?”

“I’ve no idea. Did you notice anything or anyone unusual—say, in the last six days?”

“Unusual? Well, yesterday, yeah—” The super broke off as he reached the third floor, and he groped for the wall, chest heaving. “Fuck, it stinks up here. What the hell? Is he dead?”

“No, I believe the apartment’s empty.”

The super tried the door with obvious trepidation, and it swung open, unlocked. Both men stepped back as the stench hit them.

“Fuck!” The super hustled over, snapped up the blind and tried to open the tiny window, which was crisscrossed with spider webs. “Fuck! He’s nailed it shut. Must drive him crazy in this heat.” He turned, and his pig-like eyes rounded in shock as he noticed the mess for the first time. Books and newspapers were scattered everywhere, flung haphazardly over the floor as if by a rampage. “Fuck! Who is this guy?”

Green slipped on nitrile gloves and moved rapidly through the rooms checking for intruders and obvious signs of trouble. Twenty years of police work had inured him to most human oddities, but even he found the crammed bookshelves unnerving. Any possibility that Fraser had simply been a nice, normal guy wrongly accused of child abuse vanished from his thoughts. Barbara Devine was right. This was one sick bastard. Not the shy, vulnerable man Janice thought she was drawing out of his shell, but a man whose whole life had but a single focus—the subject of the hundreds of books and newspapers which were catalogued along every wall.

“I’m going back downstairs for a hammer to get those nails out,” the super muttered, tripping over himself in his haste to get out the door. Left alone, Green continued his search. All the windows were nailed shut, but in the bedroom he found a small air conditioner, which he turned on gratefully. It would take several hours to cool the place adequately, but at least it might soon be tolerable.

In the kitchen, he noted that Janice hadn’t even attempted to clean up but had left a note for Fraser on the kitchen table to explain that Modo was safe with her. Apart from the halfeaten food and open newspaper on the kitchen table, Matt Fraser kept a fastidiously tidy kitchen. His fridge gleamed white inside and out, full of food in neatly labelled rows of Tupperware containers. Sliced carrots, diced peppers, chopped lettuce, boiled rice and single-serving portions of left-overs. A health nut too, to top it off. Not a processed cheese slice or frozen dinner in sight. The cupboards were the same. No empty potato chip bags or lidless ketchup bottles, no duplicate boxes of Cheerios to give Green a sense of kinship. The man was seeming less human by the moment.

Yet he clearly had left the scene without bothering to clean up. Without even bothering to finish his food. This suggested two things. First, something very urgent and compelling had taken him away, and secondly, whatever it was, it had occurred at a meal time.

Had he gone on his own, or had someone forced him?

Green’s eyes fell on the dog dishes on the kitchen floor. A big bugger, the super had said, surely capable of making any intruder think twice about breaking in, and capable of making enough racket to rouse the dead if he did.

When the super came huffing back into the room with his toolbox under his arm, Green turned to him. “Have you heard the dog barking any time in the past few days?”

The super wheezed as he bent over to paw through his toolbox. He seemed to be thinking, and Green gave him time. Finally the man shook his head.

“But I’m way down in the basement. I don’t hear much that goes on up here.”

Especially with your television on full blast, Green added silently. “How long has Mr. Fraser lived here?”

The man found a hammer and straightened up, his face dangerously red from the exertion. Sweat poured down his temples and disappeared into the folds of his chins. He squinted as if that would help him muster his thoughts.

“Three, four years?”

“What does he do for a living?”

On this the super was no help. He knew nothing of the man’s private life beyond that he rarely went out except to shop or walk the dog, and he had no visitors.

“None at all?”

The super started to shake his head, then paused, sweat flying. “Recently, yeah. There was a lady come yesterday—I seen her hanging around before. Outside, like. And I think someone else came last week. I didn’t see much, just heard them go up to the third floor, and they didn’t go to Crystal’s place. Crystal probably seen them, though.”

“Crystal?”

The super fidgeted, his pig-eyes squinting almost shut. “The woman next door. She’s the only other tenant on the third floor.”

Green made a note to get to her later. Since she lived next door, she might have some useful information about Fraser’s habits or recent visitors.

The super swept away the cobwebs and pried all the windows open, billowing humid air into the already stifling room. Looking eager to get away, he asked Green if he were still needed. When Green declined, the super handed over the key with relief.

“Lock up when you’re done,” he tossed over his shoulder as he hustled out the door.

Green stood in the living room, trying to soak up Fraser’s presence. From what he could see, the man lived an existence entirely without comforts. No television, no CD player, not even a comfortable arm chair. Just a computer, a desk with utilitarian chair, and a hard vinyl couch whose main purpose seemed to be for spreading out papers. There were endless shelves of articles and text books on law and psychology, but not an action thriller or hobby book among the lot. Nothing that might engender joy.

As if the man were doing penance. Perhaps he was.

Once Green’s eyes grew accustomed to the bizarre character of the room, he realized the incongruity between the various rooms. The kitchen and the bedroom, apart from the rotting food and the dog mess, seemed meticulously ordered, indicating that the man kept a neat house. Even the organization and labelling of each shelf attested to a fastidious mind. Yet in the living room everything had been turned upside down; books and papers had been pulled out and impatiently cast aside.

Janice Tanner had made much of the rotting food and the abandoned dog, but had not mentioned a ransacked living room. Surely this would not have escaped her notice. Could someone have been here since yesterday? Fraser? In Green’s house, it was not uncommon for him to turn the place upside down for something he’d misplaced, but Fraser seemed as if he’d know where every slip of paper was. Had someone else been here? Whoever they were, whatever they were looking for, they’d been in a hell of a hurry. Or a hell of a temper.

Intrigued, Green examined the books that lay on the floor. The Child and Family Services Act, which detailed the law governing child abuse, as well as its predecessor. There was a heavy tome called Child Witnesses, and another with the lurid title of Breaking the Silence. The latter looked well thumbed, with pages dog-eared and passages underlined. Green began to read.

“Fuck! What stinks!” The querulous shriek came from the hallway, and Green glanced up just as a young woman stumbled into Fraser’s doorway, shielding her eyes from the daylight and clutching a man’s extra large cotton shirt over her scrawny frame. She recoiled slightly at the sight of Green, and glanced down as if to ensure the shirt covered her crotch.

“What the fuck is that stink?” she repeated.

Green took a guess. “Crystal?”

Her eyes slitted warily. “Who the fuck are you?”

Extensive vocabulary, Green thought. Matches the super’s. He introduced himself and steeled himself for hostility. She looked like the type whose encounters with police might have been less than amicable. When the hostility came, however, it was not directed at him.

“What’s he done? What’s the pervert done?”

“Disappeared,” Green replied. “When did you last see him?”

“He gives me the creeps. Always sneaking around with that freaky dog of his, locking himself in with six locks like he’s got the crown jewels in there. Won’t even say hi, but I know who he is anyway and don’t want him anywheres near my daughter, so I stay away from him.”

Green shifted gears quickly. “Has he ever acted suspiciously around your daughter?”

Crystal held her hand under her nose with a grimace. “What the fuck stinks? I thought I smelled something weird, but I figured it was just lazy Laslo not bothering to throw out the garbage. Smells like shit.”

With a sigh, Green decided he might never get a straight answer to his questions. Her mind was as jumpy as a spooked cat, and she looked as if she were in dire need of her next dose. He steered her back into the hall and shut the door on the offending odours.

“When did you last see Mr. Fraser?”

She chewed at her fingernails. “What day is it? Monday?”

“Tuesday.”

“Tuesday.” She frowned, as if with the effort of rallying her wits. “I don’t think I seen him since last week. Wednesday, maybe? He was going out, all dressed up.”

“You mean—”

“For the office. Grey suit, tie, briefcase.”

“He didn’t usually dress that way?”

She snorted. “He wore the baggiest, ugliest pants and sweatshirts you could find. Even the Sally Ann has nicer clothes. He couldn’t look dumber if he tried! I mean, he wouldn’t be a bad-looking guy. He’s got wide shoulders and a nice tight—” she paused and twisted her thin lips into a smirk, “butt on him, still got all his hair, even if he wears it like a dork. Way long in the back.”

“What time did you see him leave in the suit?”

“I don’t know. Lunchtime? Yeah, “Young and Restless” was on.”

“Did he seem in a hurry? Did he act strange in any way?”

“Yeah, he was walking fast. Usually he kind of slinks along, never looks at you, you know? This time it was like he knew where he was going. Plus he didn’t have that ugly dog with him.”

“Did you see him return?”

She shook her head. “But he did. I heard him later. Six locks make a lot of noise, and that time he wasn’t quiet about it.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean he slammed the door and banged all the locks real quick.”

“What time was this?”

“I don’t know,” she whined, wiping her nose. “All these fucking questions. Six, maybe? “Much MegaHits” was on, so what time was that?”

Unfortunately, the hectic pace of both Sharon’s and his lives left little room for television, but the music channel’s broadcast schedule would be easy enough to check, and if the show aired at six, the timing was interesting indeed. Six o’clock was close to dinner time. “Did you see or hear anyone else come just before or after him?”

“Well, I don’t spy on him, you know. My TV was on, and my daughter was talking to me.”

“Did you hear the dog bark?”

Her pinched face cleared. “Fuck, yeah. A few minutes after the guy got home. Just about shook the walls down. Then it didn’t shut up for days!”

And you didn’t bother to check why? Green thought but knew better than to ask. In Crystal’s world, it didn’t pay to be too curious. He held her gaze in an effort to keep her focussed. “Did you see anyone else hanging around outside or in the hallway?”

She was edging back toward her own door, which she’d left open. “Look, that’s all I know. I mind my own business, take care of my daughter, and I figure what other people do—”

“Are you talking about Matt Fraser or someone else you saw?”

She scowled and stepped backwards through her doorway. “I didn’t see anyone. Not then.”

He thought of the time span between Janice’s visit and his own, during which someone had apparently ransacked the place. “Some other time? Last night or this morning maybe?”

“I was half asleep. I can’t swear to anything.”

He pressed his advantage. “But you did see someone. A glimpse at least.”

“A glimpse is no good in court, I know, and I don’t need the aggravation. I gotta go. That’s all I can say. Maybe someone else saw more.” She swung her door shut and left him standing on her doorstep, staring at the peeling paint. But there was no sound of footsteps from within, and he sensed that she was watching him through the peephole. Merely curious, or something more?

He jotted down the interview, making a note to catch her again when she was more mellow. Crystal’s “glimpse” might be the only solid lead he found. When he returned to Matt Fraser’s apartment, it smelled none the sweeter for the fifteen minutes of fresh air. Now he began to snoop in earnest. In the bedroom he found a sparsely filled closet of bulky, styleless clothes, among them a navy suit and a handful of skinny polyester neckties, but no grey suit. The dresser contained rows of jockey shorts and neatly rolled black socks, as well as stacks of the shapeless sweatshirts and T -shirts Crystal had described. On his bedside table was an empty glass and a tape recorder but no sign of bedtime reading.

With his pen tip, Green pressed the play button and heard the soothing strains of harp music and a hypnotic voice inviting the listener to close their eyes. Recognizing it as a relaxation tape not unlike the one Sharon sometimes used after a hard day, he turned it off.

In the bathroom, the man’s compulsive neatness astounded him. One toothbrush, not the half dozen elderly ones sprouting from the glass that he and Sharon shared in the bathroom. One tube of toothpaste rolled from the bottom, folded towels and a shelf of the latest herbal remedies like ginseng and Vitamin K, plus a half full prescription bottle labelled Zoloft. Green tipped one of the pills into a small evidence bag from his pocket and jotted down the prescribing doctor’s name.

In the kitchen, the fridge door was pristinely clear, and the wall calendar was blank except for weekly appointments on Tuesdays. Presumably that was his therapy group. But in a drawer, Green finally found something out of place. Or at least oddly placed. He was searching the drawers hoping to find the man’s stash of personal papers—letters, bills, bank statements or even a wallet or day book. He found linens, cooking utensils, tools and then unexpectedly, a small black book, curled and grimy with age. It was peeking out from under the tray in the cutlery drawer as if it had been hidden deliberately. Green pulled it out and flipped through its pages, which were filled with names and addresses in a small, neat hand. He slipped it into another evidence bag, put it in his pocket and continued his search.

The man had to have some personal papers. There was no sign of a filing cabinet anywhere, but surely a man as paranoid as Janice described would hoard everything and probably squirrel it away in some secret hiding place. To search the whole living room would be a mammoth task. Papers could be hidden in plain sight, mixed among the newspapers, or hidden behind some volumes in a dusty, unlit corner. It would take a search team hours to comb this place, and that for a case that was not even his. In fact, not really a case at all.

He flicked on the computer and waited as it hummed and clicked slowly to life. Not exactly state of the art, Green observed, but then the man had little to spare for extravagance. Windows eventually appeared on the screen with a prompt for a password. Green groaned. He should have known that a privacy fanatic like Fraser would use that feature. On a hunch he tried Modo. Invalid. Quasimodo. Also invalid. He pondered his chances of plucking the right name or code from the air with almost no knowledge of the man’s life or interests. He made one last try—Hugo—and to his astonishment the screen lit up with icons. Pulling up a chair, he hunched forward and began to search. It was a short search. Other than his internet browser, Fraser had no software beyond an oldfashioned word processing program and a database. The application files were in place, but there was not a single data file in either program.

Curious to see who the man communicated with, Green connected to the internet and pulled up his email screen. Not a single email in his inbox. Same story with his “sent” box and his “trash”. Green was astounded. What mere mortal had a completely empty email account? Certainly no one in his acquaintance. Either this man stored all his files in a secret place, or someone who knew computers had wiped his entire system clean.

Green clicked through subdirectories in search of hidden files, uncovering mostly folders with recognizable program names. Under “web”, however, one folder name stood out from the rest. Mistwalker. Eagerly he clicked on it. Wiped clean. Green sat back in puzzlement. Mistwalker was a peculiar word. Even mysterious, and certainly whimsical for a man as obsessive and analytical as Fraser. But tantalizing as the puzzle was, Green was stymied, for he’d exhausted all his admittedly primitive computer skills. This was a job for the younger guys on the force.

Yet his snooping had paid off some dividends. He now had the little black address book and, with it, access to the people in Fraser’s life. On his way out, Green paused at the door to examine the locks. Crystal had exaggerated; there were only five. Plus a peephole. Each was sufficient to keep out an unwelcome caller, and two of them could only be locked and unlocked from the inside. There were no scratches or chips to suggest that any of them had been forced. If Matt Fraser had had a caller that night, after he’d arrived home and barricaded himself in, then he had checked through the peephole and opened the door of his own free will.

Pretty reckless stuff for a paranoid agoraphobic who rarely left his apartment except to walk his dog.