Читать книгу Love - Barbara H. Rosenwein - Страница 10

Introduction

ОглавлениеI didn’t always want to write a book on love. Perhaps I should have, for I was brought up in a household of committed Freudians, and Freud talked a lot about Eros. But under the spell of a wonderful college professor, Lester Little, I decided to become a historian of the Middle Ages. Given my upbringing, it was an odd decision. I tried to explain it to my parents by using what was then the lingo of my household: history is but the “manifest content” of the unconscious fantasies of the people living at the time. In other words, I was saying, history is the reported dream behind which is the real story. And I would discover that real story. I meant it. My favorite book at the time was Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams.

I soon learned, however, how foolish my plan was for a nineteen-year-old, especially one who didn’t yet know any Latin. I spent the next several decades working on languages, reading the sources, delving into the history – yes, the manifest content – of medieval history and particularly of medieval monasticism. But I retained my desire to understand what was “behind” the facts I was studying. Why did the most prestigious monks of the early Middle Ages – the Cluniacs – spend most of their time in church chanting psalms? What motivated pious laypeople at every level of society to give land to this monastery? What notions of space and violence were behind the pope’s declaration of a holy and inviolable circle around Cluny’s properties? I drew on anthropology, sociology, and ethography; I gradually left Freud behind, though never entirely.

I wasn’t interested in love then, not, at least, as a topic of study. Of course, as a kid, I thought about it. I had a best girlfriend; I had crushes; I had some really awful boyfriends who gave me great anguish and some very nice ones who gave me great joy until they didn’t. But I met my husband, Tom, early on in college. We got married right after I graduated. We had twins, Frank and Jessica. I repeated, without thinking much about it, the chant of my generation: “Make love, not war.” I didn’t realize then that love is even more complicated than war.

Eventually my focus changed, and I became interested in the history of emotions. It began in 1995, when fellow medievalist Sharon Farmer asked me to chair a session at a meeting of the American Historical Association on “The Social Construction of Anger.” As I listened to the papers and the discussion that ensued, it dawned on me that the history of emotions could be a way into that as yet unexplored material behind the “manifest content.”

Certainly, the field was wide open for new research. The main paradigm for the history of emotions at that time was the “civilizing process” of sociologist Norbert Elias, who characterized the Middle Ages as an era of impulse, violence, and childish lack of socialization, ending only with the rise of the early modern absolutist state and its emphasis on impulse control and emotional restraint. I knew that he was wrong about the Middle Ages, and I suspected that he was wrong about the later periods. But I was not sure how to find my own approach.

So, I read – historical sources, theories of emotion, newly emerging paradigms of emotions’ history. I was struck by the sheer variety of emotional norms and values practiced by different groups in the Middle Ages and beyond, and eventually I arrived at a way to think about these groups. They were (as I dubbed them) “emotional communities” – groups (often living at the same time, often equivalent to social communities) in which people share the same or similar valuations of particular emotions, goals, and norms of emotional expression. These communities sometimes overlap and borrow from one another, and they also may – generally do – change over time. Even so, they have enough in common to allow the researcher to study them as a coherent group.

I still wasn’t particularly interested in love, except to note how each emotional community dealt with it – what or whom they loved; the value they placed on love; the ways in which they expressed it. But those questions were the same as the ones I asked of all the emotions: how they were expressed, celebrated, and devalued in any given emotional community. What I wanted to do, above all, was to track co-existing emotional communities during one particular slice of time and to see how new ones came to the fore and others receded in the ensuing eras.

So I wasn’t much interested in individual emotions, although I did edit a collection of articles on anger in the Middle Ages, an outcome of the AHA panel on social construction.1 And I did see the need for and interest in such studies. Even as I was writing about emotional communities in the Early Middle Ages, Joanna Bourke published a book on the history of fear and Darrin M. McMahon on happiness.2 But those researchers were not interested in emotional communities. Bourke treated modern history and the ways in which our (primarily Anglophone) cultures use and abuse fear; McMahon was interested in Western ideas about happiness, not in Western emotions.

Eventually I found a way. First, I needed to expand my purview and write about a long span of time. That I accomplished in a book on emotional communities from 600 to 1700.3 Only then could I write a book covering the story of one emotion over the long haul. I chose the topic of anger because it was both a virtue and a vice and thus more interesting to me than, say, joy. I organized the book by attitudes: some emotional communities abhorred anger; others considered it a vice but also (in limited ways) a virtue; still others argued that anger was “natural” and thus not fundamentally a moral issue; finally (and more recently) some celebrated anger and its energizing and violent possibilities.4

Only then did I turn to love. It, too, was an emotion about which almost no one agreed. I found it even more difficult and conflicted than anger. Consider these many contradictory truths, myths, memes and sayings about it:

Love is good.

Love is painful.

Love hits like a thunderbolt.

Love takes time and patience.

Love is natural and artless.

Love is morally uplifting and the foundation of society.

Love is socially disruptive and must be tamed.

Love is forever.

Love is variety.

Love is consummated in sex.

Love is best when it is not sexual.

Love transcends the world.

Love demands everything.

Love demands nothing.

All of these thoughts, reflections, and attitudes are seductive. All demand to be heard. No wonder that, at first, I had no idea how to write a history of love. Not only does (and did) it mean so many different things, but it also involves so many other emotions – joy, pain, wonder, confusion, pride, humility, shame, tranquility, anger. Then, too, it has a multitude of motives – wishes to control, to be dominated, to seduce, to be desired, to nurture, to be suckled. It may be used to justify actions – even conquest and war – that initially seem inimical to it.

As I read, however, I began to see some of the memes coalesce. They were fantasies, stories that recurred over and over, although in different guises and contexts. And, as I looked around me, I saw that they persisted even now, in modern stories – on TV, in novels, in movies – and in the lives of my friends and family. And I began to see, too, how these enduring fantasies of love had informed – and continued to influence – my own expectations of myself towards those I love and of them towards me.

Moreover, the purposes of these fantasies began to dawn on me. They were (and are) narratives that organize, justify, and make sense of experiences, desires, and feelings that are otherwise incoherent and bewildering. My family’s revered authority, Dr. Freud, had long ago hinted at that same idea when he said that the symptoms of adult neurotics were the expressions of long-repressed infantile fantasies – complexes of feelings such as the one Freud called Oedipal and that he likened to the Greek myth.

But I need hardly appeal to Freud to understand that storytelling is a way to explain, organize, and master what people are feeling. Paradigmatic narratives are not just for children to try on, create, and then (possibly) act out. We can see their importance for adults, for example, in the work of sociologist Arlie Hochschild, though she was not talking about love. When Hochschild studied adherents of the American political right, she did not fully accept their manifest explanations of their political discontents, such as those that her affable informant Mike Schaff gave her: “I’m pro-life, progun, pro-freedom to live our own lives as we see fit.” She sought, rather, what she called the “deep story,” the “feels-as-if story – it’s the story feelings tell, in the language of symbols.”5 Mike and his compatriots’ deep story went something like this: they were standing – had long been standing – in a line consisting mainly of white men like themselves, patiently waiting to arrive at the “American Dream,” a dream of progress, economic betterment, and greater opportunities. They had suffered and worked long and hard to stand in that line. But interlopers – black, brown, immigrant – were cutting in front of them. Feelings of anger, shame, resentment, and pride all came together and made sense in this deep story. This is what I call a fantasy.

Such underlying fantasies are what L. E. Angus and L. S. Greenberg are thinking about, too, when they advocate psychotherapy that intervenes and changes the narratives that people use to understand their feelings and identities. They are the reasons why Iiro P. Jääskeläinen and his colleagues use neuroimaging to unravel “how narratives influence the human brain, thus shaping perception, cognition, emotions, and decision-making.” They explain Joan Didion’s striking essay opener: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”6

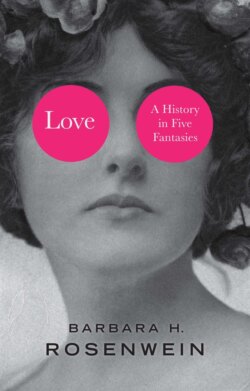

The fact that the Western imagination – only one among many imaginations – has produced some fantasies of love that span the centuries does not mean that love is love, always has been, always will be. Some stories have had staying power, granted; but they nevertheless have always shifted shape, losing some meanings and taking on others. They serve as cultural referents, and they still exert a certain frisson, but they also always need updating. Consider a New Yorker cartoon by Maddie Dai featuring a damsel in distress, a mildly surprised dragon, and a knight in armor with sword in hand (see figure 1).7 The narrative of the visual image – the knight has come to rescue the lady – is so familiar as to be almost part of our DNA. It is recycled (though never in exactly the old form) in Disney movies and childish daydreams. But the caption sabotages the expectations set up by the picture: the joke is that this particular knight is a modern guy. He queries the endangered lady about her reproductive desires and her financial philosophy before deigning to slay the dragon. Yet our laughter at the joke may be a bit bitter, for the idea that love implies self-sacrifice, that it is or should be unconditional, remains today an active ideal. In philosopher Simon May’s view, “to its immense cost, human love has usurped a role that only God’s love used to play.”8 This fantasy requires the impossible of human love, and yet it is a demand and expectation in some circles.

But not in all. And therein lie the emotional communities of love. For even as some people see “true love” to be patterned on Christ’s gratuitous self-sacrifice, others understand it as an ecstatic experience that takes them beyond the earthly realm. And others adhere to still different enduring narratives of love. These fantasies and their transformations over time form the chapters of this book. Yet it is only their entwined histories that allow us to glimpse the many-faceted, indeed kaleidoscopic, history of love within the Western tradition because, to some degree, they always played off of one another – and because they are all available to us, however loyally we may adhere to one or the other.

Unlike some scientists today, I do not wish to claim what love is. Contrary to many philosophers, I have no idea what it should be. And, unlike intellectual historians, I do not want simply to survey past theories of love (though some of those theories do enter into my discussion). I want to understand what people think love is today and what they have thought it was in the past. I want to include women in the story. And I want to cite both “real” people and what they said about their loves alongside the fictions that so often provide the scaffolding for the fantasies of love that we elaborate and hang on to.

I have chosen five persistent narratives. In the first chapter, I take up the fantasy of like-minded love. I continue with love’s transcendence – the notion that it takes us to a higher realm. Love as freedom as opposed to obligation is the subject of chapter 3, while chapter 4 confronts the fantasy that true love is obsessive and chapter 5 that it is insatiable. Each chapter is focused on a different modality and experience of love, all of which have long histories within the Western tradition. While they overlap at certain points, it may be said that like-mindedness has mainly to do with friendship, transcendence with love of God, obligation with marriages and other long-term erotic relationships, obsession with unrequited love, and insatiability with roaming.

Taken together, the threads here separated by theme form a richly hued tapestry. If it is as yet incomplete, that is as it should be, for the story of love, like love itself, is always in the process of change, re-elaboration, and new fantasy-making.