Читать книгу Rosemary Verey - Barbara Paul Robinson - Страница 9

ОглавлениеCHAPTER THREE

Creating the Garden 1960s

In a garden you get what you work for, don’t you?

IT WAS DAVID who pushed Rosemary into creating a garden at Barnsley. He first piqued her interest in the subject by buying and presenting her with old gardening books he acquired on his travels for the Ministry of Housing. He loved books himself, particularly the books he collected for his own scholarly work on the architectural history of Gloucestershire. He introduced Rosemary to the classical Greek and Roman writers, the likes of Theophrastus, Dioscorides, and Pliny, whose writings about plants influenced medieval science and medicine, along with the early herbalists who became her favorites, such as William Turner, John Gerard, and John Parkinson.

“With his understanding of Rosemary and her mathematical, geometric mind, [David] was able to nudge her. He was really a great bibliophile. He had a lot of books on Gloucestershire. He started to buy her ancient books on gardening. I think he could see that with these fifteenth- and sixteenth-century treatises … she could have a lot of fun and really make a niche for herself, which indeed she did.”1 After dinner, Rosemary would curl up in her chair for hours before the fire, sitting companionably with David while immersed in some large tome about gardens. These old herbals were hard to read but offered a window into the past, appealing to Rosemary’s interest in history and her fascination with classical patterns and designs.

The older Vereys had died not many years after giving Barnsley to David, first David’s mother in 1956 and then his father in 1958.2 David decided it was time to replace the garden that Rosemary had grassed over soon after they moved into Barnsley House. Perhaps he wished to pay tribute to his mother’s memory or perhaps, because the girls had gone away to board at St. Mary’s Calne School, he realized there was no longer any need for grassy playing fields. Whatever the reason, David chose not to wait for Rosemary to move ahead with this idea.3

But he did ask her what she proposed to do in order to occupy the time formerly spent on teaching the girls. Rosemary, still sufficiently engaged with riding and having groomed her own horses and kept the tack clean for years, asked for a full-time groom. David complied and turned his parents’ residence in The Close into groom’s quarters. Later, however, Rosemary would say that she began to tire of riding. “It became a way of life rather than an occasional pursuit. I realized then that I did not want to devote the rest of my life from September until March to hunting.”4

The timing was perfect. Rosemary was at loose ends without her daughters at home to teach, and her energies needed some outlet. She recognized that “one of the worst things about getting married and having children is that all you know about is washing nappies and ironing clothes. Unless you are exceptional, you realize you are becoming dull.”5 With a nanny and other help in the house, it is unlikely that Rosemary spent much of her time washing nappies or ironing clothes, but she firmly believed, and often said, “It’s a sin to be dull!”

With Rosemary still engaged with horses and hunting, David moved to re-establish a decent garden around their house. Without consulting Rosemary, or possibly because she expressed no interest in his undertaking, David pressed ahead. He started by focusing on the area immediately around the house and called Percy Cane, a fashionable garden designer of the day, to come to Barnsley.

Percy Cane was known for an Arts and Crafts approach to garden design, which was of keen interest to David. The Cotswolds had been at the heart of the movement that began in the late 1800s and continued into the early part of the twentieth century. Reacting to the industrialization taking place in England, and influenced by writers like John Ruskin, the movement counted William Morris among its leading proponents, advocating a return to traditional architecture and crafts produced by hand rather than by machines. His home, Kelmscott Manor, was in Lechlade, not far from Barnsley, and several prominent like-minded architects followed him to the area.6

Given his own interest in the Arts and Crafts movement, it was natural for David to engage a garden designer who championed it. When Percy Cane arrived at Barnsley without any warning, “Rosemary saw red! She’d been resisting. You can see her – eyes lighting up with fury. Getting in someone else when she was going to do it and she did.”7

Rosemary admitted Cane’s arrival “was most provocative to me. I realized that it was my garden,”8 so Percy Cane was quickly ushered back to London. No one was going to tell her what to do about her own garden. With her back up, she was determined to take charge. Looking back, Rosemary gave Percy Cane credit for teaching her one important lesson, namely “that you should always make the longest possible distance into your most important vista and give it an interesting focal point.” And it taught her another useful lesson. Remembering her own reaction, Rosemary believed that any garden she later designed had to be the client’s garden, not hers.

Before Percy Cane was sent packing, he did suggest the basic outline for the borders just outside the south-facing door of the drawing room at Barnsley House. Here, years before, Linda Verey had planted parallel rows of tall Irish yews, marching like stiff green sentinels along the path that led away from that door out to a gate that opened through an existing stone wall to the farm lane beyond. In the 1770s, an early owner, the Reverend Charles Coxwell, had built a high stone wall on three sides of the grounds, starting at the southeastern end, turning to run along the south and then turning back again. A small Gothic Revival-style gardenhouse remained at this northern end of the wall, serving as a full stop feature and garden folly. Beyond the end of the garden wall, a yew hedge hid the swimming pool Rosemary and David had built at the furthest northwestern edge.

Although Rosemary had not eliminated the tall yews when she grassed over the gardens of her mother-in-law, there was only grass on either side of the yews when Percy Cane arrived. In place of open lawn, Percy Cane outlined four symmetrical triangular beds on either side of the yew-lined central path. Each triangle had a gentle curving hypotenuse to contrast to the sharp right angles of the other two sides. This design, quite simple but classical, was appropriate to the age and architecture of the house. The four beds, later called the Parterres, would become the heart of Rosemary’s garden at the rear of Barnsley House.

Originally, the farm lane just beyond the stone wall had served as the main village thoroughfare, but after the introduction of the automobile, a broader paved parallel road had been built further north. As a result, the drawing room door looking out over the Parterres and the yew walk toward the farm lane beyond would once have been the front entrance of the house. Instead, after the paved road arrived, the north facing façade became the front entrance, facing this main road that connected the important town of Cirencester to the south with the charming village of Bibury to the north and continued on through the heart of the Cotswolds. A handsome pair of iron gates connected the driveway to this busily trafficked road. Alongside the driveway’s edge, another stone wall ran uphill to the house, behind a row of handsome large trees; in early spring, the ground is awash with aconites blooming a sea of yellow. Linda Verey had planted formal herbaceous borders in the front of the house, where the sloping land had been terraced. In her eradication phase, Rosemary eliminated these borders and simplified the terraces, leaving an unfussy, quiet green area at the front entrance of the handsome three-story house.

Before Cane’s arrival, Rosemary already had begun experimenting with a few plantings of trees and shrubs at the southwestern edge of lawn, just beyond the Gothic Revival gardenhouse, with no formal wall or enclosure there other than the yew hedge hiding the pool. She described this area “as somewhere between a woodland and a wild flower meadow.”9 She called it the Wilderness. The very name suggests the influence of William Robinson, whose influential book, The Wild Garden, and later writings passionately called for a more natural approach to gardening in England. Robinson, who was influenced by John Ruskin as well as the American Frederick Law Olmsted, would have been embraced by anyone like David Verey interested in the Arts and Crafts movement.

Rejecting the Victorian gardening style of bedding-out tender plants in highly formal, geometric-shaped areas, William Robinson preached a more naturalistic and picturesque approach. Rosemary wrote about this shift in gardening style away from the formal bedding-out of tender plants, noting “William Robinson crusaded to change the fashion to a more permanent mixed and herbaceous border.”10 Robinson was an important influence on Major Lawrence Johnston, an American who created his magnificent gardens at Hidcote Manor in Gloucestershire, not far from Barnsley. Hidcote was certainly known to Rosemary. Further away in Kent, Vita Sackville-West’s gardens at Sissinghurst Castle and her widely read garden writings were also influenced by Robinson’s views.

Given her own early university studies in social history, Rosemary was well aware that styles evolve, and from her library, that garden styles were no exception. “Like cooking, gardening is tremendously influenced by social history. At the turn of the century, cheap labor and cheap coal meant people could have fleets of gardeners and enormous hothouses. Because lots of exotics were coming into this country from around the world, extra flowerbeds were created to fit everything in. In those times, the ladies of the house often knew little of their garden. Now that situation has changed and in many cases for the better.”11

Like any beginning amateur, Rosemary’s first efforts in her wilderness were not too successful. As a novice, she began to regularly attend the Royal Horticultural Society flower shows at Vincent Square in London and visited many gardens, taking constant notes. Absorbed by trees and shrubs, she wisely consulted a tree expert, Tim Sherrard, at a local nursery. In contrast to her later, more effective, formal areas of her garden, The Wilderness was rarely noticed or photographed, probably because it wasn’t much more than a collection of fine but somewhat randomly placed trees without any structure, vista or focal point.

In due course, Rosemary herself admitted that the Wilderness was not something she took great pride in, much as she continued to admire many of the plants there. “Now inevitably, I would like to treat a few (trees) as chessmen and move them round the board.… I would do at least three of each crab and cherry instead of a single to make a bolder accent. These mistakes are the price paid for an amateur instead of a professional layout.”12 However, this particular amateur was a keen observer and critic of her own efforts, learning from these early experiences.

By Christmas of 1961, Rosemary was far enough along in gardening that her daughter Davina gave her a book to serve as a garden journal. Rosemary knew enough about the growing conditions in her garden to remember “My daughter gave me a notebook importantly titled ‘Gardening Book’ on the opening page; below I added the words: ‘Be not tempted by plants that hate lime.’ ”13 The following year, her son Charles gave her a membership in the Royal Horticultural Society. Although she continued to enjoy her horses and tennis, she faced a steep learning curve in the garden. As she learned about plants, she was fortunate to have David bring his architectural talents to bear on providing the bones of the place.

In 1962 David placed a jewel in the garden. He acquired a small, classically styled Temple, suffering from years of disrepair and neglect at nearby Fairford Park. He had it moved stone by stone to Barnsley where he sited it just behind an existing reflecting pool located in a walled corner off to the east side of the Parterres. This corner of the garden had served as his parents’ private retreat during the years they lived in The Close. After their death, David had installed this small pond to replace what had been his parents’ lawn. By chance, the measurements of the elegant Temple perfectly aligned with the width of the pool and anchored one end of the garden with a beautifully proportioned set piece of formal architecture. In hindsight Rosemary observed, “Men gardeners will do things like moving temples. I wouldn’t have done that and I don’t think [David] would have been all that good at designing borders.”14

David also rescued a set of iron railing with double gates which he placed in front of the Temple with its pool to create a sense of enclosure; he chose to paint it a surprising but pleasant deep blue, the perfect foil for the profusion of plants that Rosemary would add to scramble through it.

David then planted an avenue of lime trees (Tilia platyphyllos ‘Rubra’) in line with the Temple leading away toward the garden wall at the far western end. Because there are no straight lines in old houses, David soon realized that his parallel rows of nine lime trees seemed to veer off sideways because the old stone wall running alongside was not truly parallel to the house causing his trees to run off at a slight angle. Correction came in the form of optical illusion or an architectural trick. Nicholas Ridley, their local Member of Parliament and a grandson of the late, revered architect, Sir Edwin Lutyens, gave “an instant pronouncement. Plant another line of limes!”15 And plant them to compensate for the problem by slowly increasing the space between each tree in the double row. To the untutored eye, these two rows of limes, one a single row and the other a double, now appear to be perfectly straight.

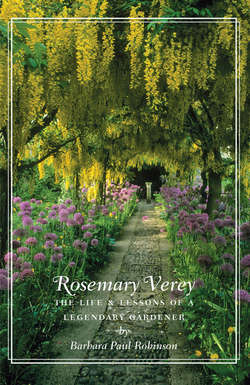

To complete this avenue effect, Rosemary asked her brother Francis and his wife Gill for a gift of laburnums and wisterias. Or to be more precise, Rosemary ordered the plants and informed the Sandilands that these plants would be their anniversary gift. “I have bought as a silver wedding present from you, Francis, ten Laburnum and ten Wisterias for an extension to David’s lime avenue. When the bill comes I will send it to you! I think it might be quite something one day!”16 It was just like Rosemary not only to expect a gift but to dictate the choice and then buy it herself. She knew exactly what she wanted and made sure she got it. Indeed her words proved to be prophetic. The laburnum allée would not only “be quite something one day,” it would become one of the most photographed and iconic of garden images.

Where did this idea of a laburnum allée come from? Certainly the magnificent one at Bodnant, now a National Trust property in Wales, was well known at the time. Given its grand scale and fame, it is hard to think that its existence wasn’t at least known to Rosemary. But she claimed not to have been influenced by the Bodnant laburnums, nor to have seen them before she created her own, or “ours might have been wider.”17 She credits instead Russell Page’s Education of a Gardener, published in 1962, for causing her to think about focal points and a long axis, something that was sorely missing in her Wilderness.

Nearer to home, Nancy Lancaster – living at Haseley Court in neighboring Oxfordshire – had also created a beautiful laburnum walk in her own garden. Nancy Lancaster was an American living in England with a great sense of style. She became well known for founding the decorating firm of Colefax and Fowler, which promoted the “English country house” style in furnishings and fabrics. One of Rosemary’s gardeners, Nick Burton, would later observe, “The lovely irony is it took an American [Nancy Lancaster] to teach the English how to decorate their houses.” Rosemary certainly knew and must have been influenced by Nancy who would later be among the women featured in Rosemary’s first book.

Did either or both of these earlier laburnum walks inspire Rosemary’s choice? While it is impossible to know, Rosemary does not credit either source, although she was usually generous in acknowledging the influence of others. Her own garden designs are not necessarily original. What Rosemary did do, and do brilliantly, was to adapt existing designs and make them fit into her relatively small garden, there to be enriched by her extraordinary sense of color and stunning profusion of plants. First-time visitors to Barnsley are often surprised when they see how small the scale actually is of this oft-photographed laburnum walk. There are only five laburnums on either side of the path and wisteria was planted to climb through each laburnum, adding their touch of purple flowers to mix and bloom simultaneously with the yellow laburnums. She underplanted the row with the purple globes of Allium aflatunense to complete the picture. This vision of yellow and mauve blooming together for almost three weeks every year called for a high degree of horticultural skill to insure all the plants were happy, and that the wisteria didn’t strangle the laburnum.

The composition was perfected when David added his quite original rough pebble path beneath the pendulous blossoms of laburnum and wisteria. David’s travels for the Housing Ministry took him as far afield as Wales, and he loved to swim, often visiting the Welsh beaches where he picked up stones and carried them home in the trunk of his car. He then spent hours painstakingly setting each small stone in cement by hand to create an uneven walk. To at least one observer, this entire enterprise seemed bizarre and the path appeared impossible to walk on. But David’s pebble path added an idiosyncratic, delightful touch to the laburnum allée. “It all looked so homespun as to be ridiculous. Anyone would trip over these huge pebbles with lots of space in between, but in fact it works. It’s great. It’s unusual.”18

Shortly before David retired from his position as senior investigator of historic buildings in 1965, he bought and restored a derelict mill that was little more than a shell in the next village of Arlington into a small, private museum. Because of his interest in architectural history and in particular, the history of the Cotswolds and the Arts and Crafts movement, he wanted to display artifacts alongside local crafts. The museum was quirky and original, containing all the things he loved. He had spent many years studying, cataloging, and grading the handsome stone churches of Gloucestershire, the so-called Wool Churches built in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries by fortunes made from sheep and the wool trade. After retiring, he had the time to spend on his museum as well as his own writing. He wrote a Shell Guide to Gloucestershire in addition to the two volumes he had produced for the Pevsner’s buildings series.19

For opening day of the museum, David invited a young sculptor, Simon Verity, to carve an inscription outside the door to attract people to come. Simon’s uncle, Oliver Hill, was a distinguished architect and knew David slightly from those circles. Simon quickly saw that he was “the carver and the act.” Rosemary admired his talents, and Simon’s wonderful statues, plinth, and fountain would later add important dimensions to the developing gardens at Barnsley.

In 1968, David was appointed High Sheriff of Gloucestershire. That office dates back to the tenth century and exists to this day as a royal appointment of great prestige and honor. The High Sheriff represents the Crown in overseeing law and order but more as a formality than a reality. Over the centuries as the professional police force developed, the office of High Sheriff had become largely ceremonial. In David’s year, he had to attend countless openings, dedications, and similar activities occurring throughout the County. He also had to equip himself with the appropriate dress to suit his title and to greet and host various visiting dignitaries, all at his own expense.

Rosemary served as his official consort and hostess. Since David was always a fairly private person, in contrast to Rosemary who always loved a party, some close observers believed that she might well have preferred to hold the title herself. “Rosemary secretly felt that she was at least half of the equation although the role was his,” her assistant, Katherine Lambert, observed.

Rosemary admitted that she intentionally deferred to David. The garden became her place to shine. “With my husband I always played my success very low key on purpose, because he was the clever one. That was how I saw it and that was the way I played it. He was full of charm and everybody loved him. But he wasn’t a natural in the garden. That was my area.”20 She was not alone. As with so many women before her, the garden had an emancipating effect. It was “a domain in the pre-feminist era which they could set out to conquer, and they did,” observed the historian Jenny Uglow.21 Although at this early stage, Rosemary never thought of making it her career, she knew herself well enough to admit that when she did something, she did it wholeheartedly.

Looking back on their partnership, Rosemary was insightful about the different roles she and David played in creating their garden. After the war and the loss of the head gardener, she asked, “Who has taken charge of the garden? It’s usually the woman of the house. And this has been a way for her to express her artistic talents. She’s learned about plants and she’s learned about color coordination and she’s really enjoyed doing it.” Then with a slightly annoyed tone of voice, she noted, “Usually, it’s the man who has control of the money!” Hence it is the man who says, “Why don’t we plant an avenue, why don’t we make a lake, why don’t we change the drive, and he is in the position to be able to do the much more hard landscaping, the things that are going to be more expensive to do.”22 Certainly this was the case here with David in control of the money and David focusing on the architectural features of their garden.

David also assumed important leadership roles in the Church, serving on the Diocesan Advisory Committee, a highly regarded position. Eventually he became Chair of that committee, a position he held for seventeen years. Rosemary joined him in her commitment to the church. They both served as warden at various times and Rosemary arranged and delivered flowers faithfully every week. Members of the congregation found it very hard to say no to Rosemary when she decided they should perform some service. Once when Anne de Courcy, the parishioner Rosemary had selected to write a history of the church, hesitated, “her eyes swiveled around … in that well known way … and after a direct gaze from Rosemary,” she capitulated.

When the church meetings were in the evening, Rosemary could become confrontational, especially when she had been drinking. She could be prickly, but at least she was also self-aware. Anne recalls she acknowledged that, “If I’m on anything, I feel I have to run it. I feel I have to be Queen Bee.”

While Rosemary was busy supporting David in his High Sheriff role and in the governance of the Church, she continued to enhance her knowledge and horticultural skills. She began to learn about mixed borders, herbaceous plants, and spring bulbs. She had a misting system installed in one of the existing small greenhouses and started propagating plants there. Like any new enthusiast, she entered specimens of her plants into the RHS Flower Shows and competitions, winning a ribbon as a first-timer for one of her unusual willows from the Wilderness (Salix daphnoides aglaia). She continued to read voraciously – especially more contemporary books – visited gardens, took notes, and listened to the advice of others.

One local plant mentor was Nancy Lindsay, the only child of Norah Lindsay, who had been a socially prominent, much-sought-after garden designer before her death in 1948. Along with her mother, Nancy had been a close friend of Major Lawrence Johnston, the creator of Hidcote, where she ran a small nursery. Hidcote is now one of the star properties owned by the National Trust. Lawrence left his other garden in France (called Serre de la Madone) to Nancy when he died. Rosemary visited Nancy at the garden her mother Norah had created at The Manor House at Sutton Courtenay where she made copious notes. One important precept Nancy taught Rosemary was to start by growing easy plants, so she would be gratified by the results. Then she could increase her repertoire, expanding into rarer and more exotic species. It was wise advice to use plants that would thrive and flourish, rather than starting out with finicky rarities that would likely die. Nancy sold Rosemary hardy geraniums, hellebores, hostas, and other similar good plants, suggesting that rare treasures could be tried by tucking them in among these strong performers.

Although Percy Cane had urged her to always create vistas using the longest axis across the garden, it took Rosemary quite a long time to comply. Finally in 1968, she opened a vista that began at the Temple and continued for over one hundred yards to the old stone wall at the opposite end. She removed an old lonicera hedge and other obstructing plantings, which were replaced with a wide grassy walk, flanked on one side by the limes and laburnums and the other by a newly developing area Rosemary called her long border. Acknowledging Gertrude Jekyll’s advice, Rosemary incorporated yellows in this border, to “create a feeling of sunlight. A glowing yellow took over what had once been drab and was now alive.”

By the end of the 1960s, Rosemary felt confident enough about her developing garden and skills to begin to write short articles for The Countryman. This was not a garden magazine per se, but a quarterly publication devoted to the issues surrounding rural life. The Countryman describes itself as “A Quarterly non-party review and miscellany of rural life and work for the English Speaking World.” Published in Gloucestershire, The Countryman’s topics ranged from articles on birds, fishing, shooting, and decoys to advice for farmers, with a scattering of cartoons, often depicting oafish farmers.

Rosemary’s first writings appeared in 1968 in a two-part article entitled “A Garden Inheritance” in which she described Barnsley’s garden and its evolution. Crediting the influence of others and attending the Royal Horticultural Society shows at Vincent Square, she included practical advice along with her enthusiasm, noting how important it was to bear in mind the limey Cotswold soil. So began Rosemary’s regular writing for The Countryman. She first wrote a couple of articles on her own garden before becoming a regular contributor, with several others, to a section entitled “Hints from the Home Acre.” She usually wrote a short page or two on specific plant topics and how to grow them. She encouraged her readers to visit other gardens, as she had done herself when she began, and to keep notes of the plants coveted from a friend’s garden, ones that have long summer bloom, prove reliable in the English “unsummery summers,” require no staking, and prove to be good mixers.

Rosemary always took notes herself and encouraged her readers to do the same. “Good plant associations play a vital part in achieving a successful garden and creating them is a constant fascination. If you have kept an eye open for effective combinations in other people’s gardens and remembered to make a note of them.” She also used her eyes. “I have cut a stalk of ceanothus and carried it round the garden to find other good combinations.”23

By 1970, Rosemary had her first article published in the prestigious magazine Country Life, writing about the fruits and flowers of Nassau after she and David had taken a trip there. Here, again, she followed David, for he had an article published in the magazine a year before and would have several more in 1970, 1971, and 1973 about historic churches, the Georgian buildings of Nassau, and related architectural topics. Her first article was a complement to David’s; she’d have to wait nine years for a second appearance. But by that time, she wrote on her own.

In that same year of 1970, Rosemary turned fifty-two and opened her garden to the public for the first time. It was only for a single day as part of the National Gardens Scheme, but it was a start.