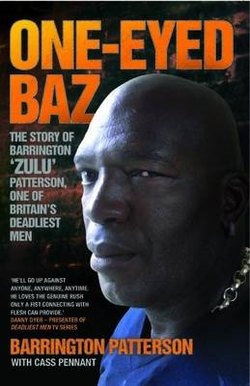

Читать книгу One-Eyed Baz - The Story of Barrington 'Zulu' Patterson, One of Britain's Deadliest Men - Barrington Patterson & Cass Pennant - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER ONE

ОглавлениеI never had any real problems at my first junior school, Farm Street in Hockley – which was later demolished. At home though, me and my sisters and brother all used to play around, argue and fight with each other all the time. It was competitive – with broomsticks, mops, whatever – but it never got to the stage where we pulled out knives on each other. None of us ever picked on an outsider either; it was always only each other.

One day, when I was seven, my sister Jennifer and I were playing in the garden. We often played together, as she was older than me by one year and she never had any fear of me. Jennifer is the oldest one over here – I’ve also got an older sister and brother in New York. She thought she ruled the roost – but I thought I did; I’m not the older one, I’m the bigger one!

On this particular day, we had an argument and, in anger, she dashed a full can of Coke at my head which caught me in my left eye. She meant to throw it at me – it was a woman’s anger – but I’m she sure didn’t mean it to cause the harm it did. I just felt the whack! And then I had blurred vision in my eye. It was like being punched on the jaw – you just feel a sharp pain. Then my mum took me aside, sat me down and put some water on my eye.

She could see something was wrong, and I was immediately rushed to A&E at Dudley Road hospital in Birmingham. At the time, the hospital had the nickname ‘Slaughter House’, because everyone who went there seemed to die, the thought of which was going through my seven-year-old mind. I was diagnosed as permanently blind in one eye that same night.

I never noticed anything different about my eyes though. I was young and I soon adapted, but to other people I became the playground joke. They called me ‘One Eye’, as my left eye was much smaller and obviously sightless. When I had my first fight, at eight years old, I got beaten up by two black kids of the same age who called me ‘Cyclops’. I took a real beating; I felt really angry and went home to tell my mother, who cussed me in patois and told me, ‘Fe gwan back out and fight back de bwoy!’

I never did. I was too scared and there were two of them, but it taught me a lesson and convinced me to get tougher. I continued to have playground scuffles at least once a week and would win nine times out of 10. I started to like it; I loved the buzz, and I firmly believe that this shaped my character into what it is today.

* * *

I was born on 25 August 1965. My mum, Dorothy Pearson, met and married my dad, Karl Kenneth Patterson, in Kingston, Jamaica. He first came over here in 1958, and then he brought my mum over to England to live with his mother, who was a nurse in Burton-on-Trent. My mum and dad had five kids together after my dad settled here, working in a factory. She already had two kids back in Jamaica – a boy named Christopher and a girl, Joy, who now lives in New York. When my mum came over here, she let Joy remain with her own mum’s family, as was the way with so many Jamaicans who, like my mum and my father’s mum, came to this country in search of a better life. Joy and Christopher made their own way. I keep in contact with Joy and visit her when I can, as I do with my stepbrother, who still lives in Jamaica.

After my parents settled in Burton-on-Trent, they went on to have five children. My sisters Jennifer and Sara and a sister who died of cot death in the 1970s, me and my brother Eric all had the Patterson surname. My mother would return to visit Jamaica on various occasions, but we lived in Burton until I was about four years old. We lived in a house on a hill with a garden that backed on to fields, where there were horses and cows.

We had to move to Handsworth, Birmingham, where my mum’s mother lived at the time. My dad had got into some trouble and was sentenced to eight years in prison. I never really knew my father until I was about 14 years old; before that I have little recollection of him at all. I knew from my mum that he was in prison and that was all I needed to know; as we were children, it was never discussed further. He’d had an argument with an Asian man who came to our house, and my dad grabbed a knife from the kitchen and stabbed him, something he confirmed to me later.

I have one other memory of Burton when I was a kid: it was before a visit to my grandmother’s. My dad was still out of prison then and he was there when my mum tried to leave with us. He refused to let us go, but the police were called and we were escorted out.

Because my mum effectively became both Mum and Dad, and Gran was always around the house, I never felt that having my dad in prison affected me while I was growing up. I got the impression my dad was a bit of a rogue himself, from the stories he told me later when he came out of prison. For a time he’d lived in Bermondsey, south London, and it was a hard area with not many black people, where there would be scraps with teddy boys.

Handsworth was really multicultural in contrast to where we’d just come from. When we moved into my grandmother’s four-bedroom house in Lozells Road, I started to realise that there were more black people outside of my own immediate family – not just black, but Asian and other races too. The other change in my life was that my gran, Ina Johnson, took the role of my mum, now that she had to do several jobs to keep and sustain us all. The four of us had been brought up just by my mum and we never ever had a thing.

Then, a couple of years later, my aunt split up with her fella down in London, so she came to live with us as well. My sister Jennifer is a year older than me, Sarah is a year younger and my brother, Eric, was three years younger. With just a few years between us all, now we had our cousins living with us too – when my mum’s sister got her divorce and moved in with five kids, who were all similar ages to us. Now there were three families in one house in Lozells, all trying to survive and look after one another. We used to take turns in sharing the beds and using the bathroom.

The Asian family living next door were the same – overcrowded. Everyone was, but you all got on. The Asian family used to bring some food over to the house; it was a close-knit community, black, Asian and white people were just as poor as each other. In Lozells, everyone was in it together and the only segregation was from the police. I’m a Lozells man – that was my area.

I had a good relationship with my mum but I had a lot of energy as a boy. We were a typical Jamaican family that ran a strict household. If my gran said we had to go to church, then we had to go to church. It would be the sort of church where you’d vocally praise the Lord, with all this singing and shouting ‘Hallelujah!’ There would be church in the evening too, plus Sunday school, and you had to go: my grandmother used to say, ‘No church, no dinner.’ She had a big influence on us.

I stopped going to church when I was about 13; I felt old enough to make my own mind up. The rest of my family still attend and still try to convert me. I always say the same thing: ‘The only time you will see me in church is funerals and weddings.’ I believe in God – I just don’t feel the need to go to church.

It wasn’t easy growing up in a Christian family, what with being a football hooligan and getting nicked for fighting. You can imagine what my mum used to say! But she accepted it was my way of life and she always stood up for me – no matter what. She just accepted that’s how my life was.

Amidst all the madness, my mum met and settled down with a nice bloke called Shaggy. He was a good man and they went on to have a daughter, Lorraine, who now lives with my mum and takes care of her since Shaggy passed away. I have a special bond with my half-sister and I’ve always had time for her.

* * *

Lozells is also the area where I went to school, at Farm Street. Those were the days of the Rastas and their sound systems: Observer, Eternal Youth, Jungleman, these were the sounds of the day. There was music coming from every street corner, like it was a festival every day. Rastas burning spliff stood on corners as police drove by; some guys didn’t think about doing it undercover, it was like they wanted everyone to know.

I’ve always been into sports, rather than being academically minded. My first introduction to a fighting sport was after another scuffle, when I was nine or 10, and I walked past a local church-hall sign saying, ‘Judo lessons here.’ So the following week, I went along and joined there and then, just on my own. They made you wait and then you had to bow to everyone, including your opponent, and bow before you went into the dojo, which you couldn’t enter with anything on your feet. It added a bit of discipline, because before that I was a bit of a rogue. This was something different to coming home and changing out of my school clothes to run around the street. I ended up doing judo two or three times a week there for five to six years, and I earned my purple belt before I stopped and went back to the streets.

My motivation for judo was that I wanted to learn how to fight properly and increase my ratio of wins to 10 out of 10. By this age I never wanted to lose a fight again.