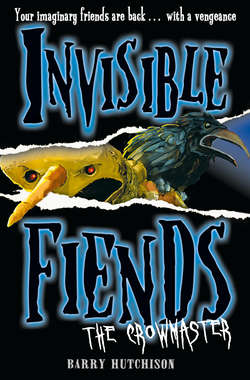

Читать книгу The Crowmaster - Barry Hutchison - Страница 9

ОглавлениеChapter Three A GOODBYE

I have no memory of moving. I don’t remember hurling myself at Mr Mumbles, or how I managed to reach him before the axe could find its target.

All I remember is my shoulder hitting him hard in the chest and the sound of the air leaving his body in one short sharp breath.

We tumbled, a flailing ball of arms and legs, through the door into Ameena’s room. He was laughing before we hit the floor, that low, sickening cackle I’d heard too many times before.

My fist glanced off his chin. He didn’t flinch. Kept on laughing. I brought the sparks rushing across my head. Pictured my muscles bulging. Faster. Stronger.

Bam. The next punch twisted his head around. That shut him up, but I hit him again anyway, across his crooked nose this time. It split with a crack, spraying thick black blood on to the carpet.

This time I was getting rid of him for good. There would be no coming back from what I was about to do to him.

How many times did he try to strangle me at Christmas? Four? Five? I’d lost count of how often I’d felt his hands around my throat. Now it was my turn. My fingers wrapped around his windpipe and I pushed down with all my weight. His eyes bulged and his grey skin took on a purple hue as I choked whatever passed for life out of him.

I heard a sound on the carpet right behind me. Caddie, I thought, releasing my grip and twisting at the waist. The lightning zapped through my brain before I knew what was happening. Mum was lifted off her feet and driven backwards into the wall. It shook as she slammed against it, hard enough to send some of Nan’s old ornaments toppling from their shelves on the other side of the room.

I was on my feet at once, Mr Mumbles forgotten. Ameena was at Mum’s side before I was, kneeling down, checking she was OK. Mum groaned and edged herself into a seated position against the wall. Her face was contorted in pain, but there was something else there in her eyes when she looked at me. Something I’d never seen before.

Fear.

‘Mum, are you all right? I’m sorry,’ I spluttered. ‘I didn’t know it was you. I thought…’ My words wilted under her gaze. ‘You saw him, right? You saw him?’

She nodded, but her eyes didn’t leave mine, and the expression behind them didn’t change.

‘He’s gone,’ Ameena said, standing up and searching the room. ‘Where did he go?’

We were right by the door. There was no way he could have got out that way, but Ameena ventured on to the landing to check anyway. She returned a second later and gave a shrug.

‘Disappeared,’ I said. ‘Like before.’

‘You were going to kill him,’ Mum breathed.

‘I had to,’ I told her. ‘He was going to kill you.’

Mum’s eyes searched my face, as if seeing it for the first time. ‘But the way you flew at him. The way you were hitting him…’ Her eyes went moist and she looked down at my hands. Mr Mumbles’ blood still stained my knuckles.

‘You were going mental,’ Ameena said. I shot her a glare, but she fired it straight back. ‘We were shouting at you to stop. Didn’t you hear us?’

I nodded unconvincingly. I hadn’t heard a thing.

Mum winced as she tried to stand. Ameena and I both held out a hand to help her up. She looked briefly at mine, then took Ameena’s.

‘What’s the problem?’ I asked, more aggressively than I meant to. ‘I had to do it. I had to stop him. Don’t you get that?’

‘Downstairs,’ Mum said, placing her hands on her lower back and giving her spine a stretch. ‘You and I need a little talk.’

‘But, Mum—’

‘Downstairs, Kyle,’ Mum said, not angry but sad, which was worse. ‘It wasn’t a request.’

I sat in the kitchen, listening to the cheeping of the birds outside, and the distant rumblings of the first of the early-morning traffic. Mum’s ‘little talk’ had become a long discussion, and although it was still mostly dark outside, the clock on the wall told me it was almost seven.

The hot chocolate Mum had made an hour ago had gone cold. It sat in a mug on the table in front of me, untouched. I was too stunned to drink any of it. Too shocked by what Mum was suggesting to do anything but fight back the tears that were building behind my eyes.

‘It’s for the best,’ Mum said. My gaze was lowered to the table. I could see her hand resting on top of mine, but I couldn’t feel it.

It’s for the best. She’d said those words nine times during our two-hour conversation. Only It won’t be for long challenged it for the coveted title of Most Overused Phrase. They had been neck and neck almost the whole way through, but this last instance had pushed It’s for the best into a nine-eight lead. It was nail-biting stuff, and concentrating on the game was probably the only thing that was stopping me from crying.

‘I’m sorry, Mum, it was an accident,’ I said croakily, raising my eyes to meet hers. ‘Don’t do this, please.’

‘I promise, sweetheart, it won’t be for long,’ smiled Mum weakly.

Nine all.

‘It won’t happen again, I swear.’ ‘It’s not that you hurt me. That’s not what I’m worried about,’ she said. ‘I’m worried about you. And Ameena. And… and everyone. If you’ve started making those… those things come back, then no one’s safe. No one.’

Part of me knew she was right. If I was somehow making the enemies I’d faced return, it would be dangerous for anyone to be around me.

Another part of me was even more worried, though. Mr Mumbles was dead. Caddie was dead. There shouldn’t have been anything left of them to come back.

Could it be that by picturing them so vividly I was somehow creating them? Was my imagination bringing them to life? It sounded impossible, but everything I’d been through in the past few weeks had made me take a long hard look at my definition of “impossible”.

Despite all this, despite everything I knew and everything I suspected, there was one thing keeping me from agreeing with Mum’s plan.

‘But… I don’t want to.’

She squeezed my hand and glanced towards the window. Before she turned away I saw the softness in her eyes. A butterfly of excitement fluttered in my belly as I realised she wasn’t going to go through with it. She couldn’t.

When she turned back, though, her expression had changed. The softness was still there, but a wall of determination had been built in front of it.

‘I’m sorry, Kyle,’ she said in a voice that told me the debate was now over. ‘But you’re going to have to leave.’ She gave my hand another squeeze, before adding: ‘It’s for the best.’

Ding ding, I thought, as the first of the tears broke through my defences and trickled down my cheek. We have a winner.

Four hours later I was on a train, wedged in tight against the window by one of the fattest men I’d ever seen in my life. The carriages were all pretty busy, and I had considered myself lucky to find a seat at all. Now, jammed there with my arms pinned to my sides and my face almost touching the glass, I wasn’t so sure.

He’d joined the train at the stop after mine. From the second he squeezed himself into the carriage I knew he’d end up next to me. There were two or three other seats free, but I knew my luck wasn’t good enough for him to choose one of those. Sure enough, he heaved himself along the aisle until he was level with my seat, then plopped down next to me with a heavy grunt. No matter which way you looked at it, this really wasn’t shaping up to be a good day.

The track clattered by beneath us; a regular rhythm of clackety-clack, clackety-clack. The train shifted left and right on its wheels. Every time it swung left I found myself squashed further by the bulk of the behemoth beside me.

It was an hour or so to Glasgow, where I would have to get off this train, go to another station, and get on a second train. Then it was nearly three hours until my stop, where I would be met by Mum’s cousin, Marion. From there it was a ten-mile drive to Marion’s house, where I would be living for at least the next month.

Mum had shown me the place on the map. It was a remote little house located slap bang in the middle of nowhere. Apart from the train station there seemed to be nothing within twenty miles in any direction. Mum had described it as ‘perfect’. I guessed ‘painfully dull’ would probably be much more accurate.

I still didn’t want to go, but Mum’s reasoning for sending me to Marion’s did make sense, I had to admit.

It was our house, she said. Huge chunks of the horrors I’d experienced in the past few weeks had taken place in the house, and Mum believed just being there was what was making the bad memories so vivid. Vivid bad memories, it seemed, led to very bad things happening.

She reckoned being around her and Ameena could also be contributing. It was just after she said this that she dropped the bombshell about going to live with Marion. She hoped the change of scene would help me to stop conjuring up anything that might try to kill me. I’d probably just die of boredom instead.

Marion didn’t have any children, which was another reason for sending me there. Mr Mumbles had been my imaginary friend, and Caddie had been Billy Gibb’s – a boy from my class in school. If they only came back when the child who imagined them was around, then taking me away from children should keep me safe from any more homicidal visitors. At least, that was the theory.

‘Nice view.’

The huge man in the seat next to me was leaning into my space, admiring the scenery as it whizzed by the window. His face was red and sweaty, as if he’d just completed a marathon. He was completely bald, and as he breathed I could detect a definite whiff of milk. Stick him in a giant nappy and you could have passed him off as the world’s largest baby.

I quickly pushed the thought away. The last thing I needed was for that mental picture to become a reality too.

‘Yeah, it’s nice,’ I replied, looking out at the fields.

‘See the little birdies?’ he asked, jabbing a podgy finger against the window. ‘Pretty.’

Ignoring the urge to point out to him that he wasn’t talking to a three-year-old, I followed his finger. A large flock of black birds was flying parallel to the train, about thirty or so metres away. They moved as one, all soaring in perfect time together, as if taking part in some carefully orchestrated dance.

‘How are they keeping up?’ I mumbled, not really expecting an answer. ‘We must be doing eighty miles an hour.’

‘They’re crows,’ he said, as if that somehow explained things.

‘Are crows that fast?’

He made a sound like air escaping from a balloon. SSSS-SS-SS. It took me a moment to recognise the sound as laughter. ‘Them ones are.’

I kept watching the crows. I doubted they could keep up this pace for long. Any second I expected them to fall back and be left behind by the train, but they remained level for several minutes. If anything, they seemed to be pulling ahead a little, although I couldn’t be certain of that.

‘Where you off to?’ The man-baby’s voice was close by my ear and I gave a little jump of fright. We were so close he must have felt my sudden jerk, but he didn’t let on if he did.

‘Glasgow,’ I said, not wanting to give away too much information.

‘Big city,’ he said. Every word he spoke seemed to make him more and more breathless. I realised that was why he used as few of them as possible. If a sentence had more than four words in it he had to stop for air halfway through. ‘Shopping?’

‘Something like that.’

‘Young lad. On his own. Big city,’ the man wheezed. ‘Dangerous.’

‘I’ll be meeting friends,’ I lied. I was keeping my gaze pointed out of the window, hoping he’d take the hint.

‘Yes. You will be.’

I turned to face him, struggling against the bulk of his arms. ‘Sorry? What did you say?’

‘I’m sure you will be,’ he panted. ‘Meeting friends, I mean.’ His mouth folded into a gummy smile and I realised for the first time that he had no teeth. Maybe he really was the world’s biggest baby.

‘Tickets, please.’

I was glad the ticket collector chose that moment to appear. Anything to save me from having to talk to the weirdo next to me.

I felt like a circus contortionist as I tried to squeeze my hand down between the man and me so I could reach into my pocket. He must have realised what I was trying to do, but he made no attempt to make things easier. Bad baby. I thought, and I couldn’t help but smile.

My ticket was a little crumpled when I finally managed to haul it from my pocket. I straightened it out as best I could before holding it up for the ticket collector.

‘Sorry,’ I said, ‘it got a bit squashed.’

‘No problem,’ the collector said. He clipped a hole in the ticket, then handed it back to me. As I reached out to take it I almost yelped with surprise. The ticket collector turned and moved along the aisle, but not before I caught sight of his face and realised who he was.

I’d seen him three times before. Once in the police station when I’d been chased by Mr Mumbles, then twice at the school when I’d faced Caddie and Raggy Maggie. I had no idea who he was, but as I watched him move along the train I knew one thing for certain.

I was going to find out.