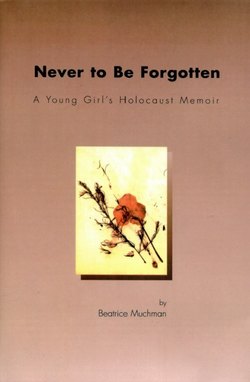

Читать книгу Never to Be Forgotten: A Young Girl's Holocaust Memoir - Beatrice Muchman - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

PREFACE

ОглавлениеThe first time I saw my father cry was the second-to-last time I saw him. I was nine years old. That was more than fifty years ago, during the summer of 1942.

We were in the Belgian countryside, in the town of Ottignies, about twenty-five kilometers from Brussels. My father had brought my cousin Henri and me there on a long train ride that morning. We were at the home of two Catholic women, where we were to spend the summer.

My father began weeping when he kissed me goodbye. The women, who were sisters, looked on awkwardly. Or maybe I was the one who felt awkward, wanting so much to look like a grownup and embarrassed to see my father, of all people, acting like a child.

I understood a lot of things by the time I was nine years old. After fleeing our home in Berlin and moving to Brussels three years earlier, after learning to speak French and, more importantly, not to speak German, after being forced to quit school and hide in our cramped apartment for fear of discovery by the authorities, I understood things that a child that age should not have to know things that too many children my age, at that time, knew all too well.

But on that beautiful summer day I did not, or perhaps would not, understand why my father was crying.

My parents had prepared me for the trip, telling me I would enjoy life away from the city—the fresh air, the sunshine, the flowers, the trees. But the way my father was behaving, spending my summer in the country seemed like anything but a good thing. He was spoiling what was supposed to be a wonderful moment in my life.

It wasn’t until much later that I came to realize why my father was crying. He knew deep inside that this very well might be the last time he would ever see his daughter, his only child. But he did not mention that to me, and I was too young to understand such a possibility.

He was gone in what seemed like an instant, rushing out the door, starting on the long walk down the steep hill leading back to the train station. I tried hard to put him out of my mind, as the two middle-aged sisters attempted to make Henri and me feel at home in our new surroundings. But when I went to bed that night, I was still thinking about my father crying. I felt frightened and alone.

Despite all the things I understood back then, despite all my efforts to see things as a mature young lady, I only knew them through a child’s eyes. When I was told a year later that my father had been shot to death by German soldiers, there was a part of me that didn’t believe it, a part of me that didn’t yet understand the finality of death. When I learned at the same time that my mother had been captured and taken away, I didn’t dare believe that she was gone forever. I was sure I would see her again and I convinced myself it would be soon. I was wrong, of course, but having that belief to cling to made it possible for me to cope and survive during a time of great personal anguish.

I’ve carried the memories from that period of my life for more than half a century now, and at many times they have been an oppressive burden. But there are also good memories from that period, of people whom I came to cherish for the rest of my life, people who were willing to risk their lives to save mine. My parents, of course, made the ultimate sacrifice—giving me up, their only child. But being a child, I had no understanding of what an agonizing decision that was for them. Not until years later, when I had my own children, did I begin to appreciate it. But at the time, and in the years following, it was hard to overcome the feeling that my parents had not saved me, but abandoned me.

Like so many other people who lost loved ones during the Holocaust, I learned very little about what happened to my parents. Most of what I knew came from my grandmother and aunt immediately after the war. Some forty years later their account was validated for me in Volume II of Belgian historian Maxime Steinberg’s, La Traque des Juifs, 1942-1944. My parents were among a mass of deportees—on a transport to Auschwitz—who attempted a unique escape. Despite the dispassionate rendering, in which my mother and father were mere numbers on a transport, reading about them on a printed page somehow made their lives—and their deaths—more real for me.

Some years later, my daughter, Wendy, made a discovery that had a far greater impact on me than reading about my parents in Steinberg’s book. It was a discovery that brought my memories of them and that period of my life into a much sharper focus. More important, it changed my life at a time when I was recovering from another personal tragedy—the death of my son in a senseless car accident.

Wendy made the discovery at the home of my adoptive father, Werner Lewy, the uncle with whom I had gone to live in Chicago after the war. Werner had died, and Wendy was helping my husband and me close his estate and dispose of his personal effects. We had completed most of the job, and on this particular day Wendy was there alone, sifting through stocks of dusty boxes on overhead shelves in a bedroom closet. The last box that Wendy found aroused her curiosity. Unlike the other boxes, it was taped shut. Inside she found a black three-ring notebook bulging with brittle yellowed papers. They were mostly faded letters, handwritten on odd-sized sheets of stationery, but among the letters there also were official-looking documents and old photographs.

Most of the letters and documents were in German, a few were in French and English. From glancing at the dates, Wendy could see that they had been written during the 1940s. Names of relatives whom she had heard about but never met leaped at her from the lines. Two names in particular stood out: Julius and Meta Westheimer. My mother and father.

Wendy was reluctant to tell me about her discovery. She was afraid it would upset me too much. A few years earlier, her brother, Robbie, my only son, had been killed by a drunk driver, and she wanted to spare me further heartache. But she soon realized that for me the value of the information in the letters would outweigh whatever sad memories they brought.

The experience of poring over the contents of that box, of seeing my mother’s handwriting again after so many years and reading about the agony that the adults around me were going through during that period of time, was indeed devastating. At first I was angry that my uncle had never’ shared the contents of the box with me during the forty-five years we both lived in Chicago. It was inconceivable that he had forgotten about them, being a person who was committed in the later years of his life to keeping memories of the Holocaust alive. Had he needed to protect himself from the painful memories, or had he been trying to protect me?

I’ll never have the satisfaction of knowing the answer to this question, but the letters themselves provided many answers to questions that I had put aside long ago, as well as to new ones that arose. like the pieces of a lost puzzle, distant dates, lives, and events came together for me in a new and clearer light. During the many months that I sat up late into the night, deciphering, decoding, and translating the tiny scribbled words crammed onto every inch of precious brittle yellowed scraps, the letters reminded me of all that I had seen and enabled me to see how much I had missed. They brought to life beloved human beings I had known as a child and others I had barely known. My mother and father once again became real and close — people I could touch and understand.

Rekindling memories that had smoldered for so many years, the letters also prompted me to go back through a diary that I had kept as a child, enabling me to compare what I observed and felt with what I had chosen to record. The neat handwriting and carefully selected words revealed how well I was able to hide my real feelings. The way I wrote is how I coped — by trying to be the perfect child, the happiest child, to please everyone around me so that I would deserve their care.

Presenting the letters and my diary and writing about these years seemed at first a way of giving my parents and the events that surrounded their tragic deaths a place to rest. It was also a way to keep their spirit clearly remembered for my daughter and any children that she may have. But it soon became much more than that. It became a deeply personal and troubling journey to my past, bringing back the fear and pain I felt as a little girl abandoned by her parents. As a child, I had not grasped the terrible circumstances and agonizing choices that my parents faced In making the courageous decision to give up their only child and hide her from the Nazis, they also had been forced to keep me hidden from seeing their love.

More than half a century later, through the good fortune of discovering their letters and reading about how I had filled them with joy and pride, I finally was able to discover, in a deep, fundamental way, that my parents had loved me more than life itself. Translating their letters and writing about those years became my chance to forgive them and embrace them and thank them.

THE BOAS SISTERS

FRIEDA (Friedel): 19001990

Business woman, bookkeeper. Most intellectual of the sisters. Studied voice (opera). Marriage arranged by parents to attorney Walter Hurwitz. Emigrated from Berlin to Brussels in 1937.

Child: Dieter (Henri)

MARGOT (Margotel, Margotchen, Mahne): 1903-1979

Bookkeeper. Studied violin and piano. Headstrong, fun-loving; talented in cabaret improvisations. Married Werner Lewy, ambitious salesman and businessman. Emigrated to United States in 1940.

Child: Bernt (Berni, Bernilein)

META (Madi, Mady, Metachen): 1904-1943

Commercial artist, fashion designer, poet. Most creative of the four sisters; wished to become ballerina. Married entrepreneur Julius (Julle) Westheimer, athlete and champion oarsman.

Child: Beatrice (Beatrix, Trixi, Trixie, Trixilein)

HELLA (Hellachen): 1906-

Youngest of the sisters, the baby of the family. Married Walter Tausk, business man and amateur boxer. First of the sisters to emigrate to United States.

Child: Flory (Florylein)