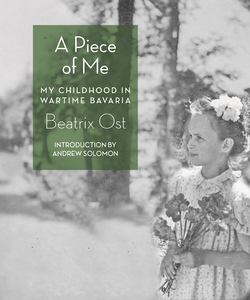

Читать книгу A Piece of Me - Beatrix Ost - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

BREITREITER

ОглавлениеThere was plenty to eat on the estate: vegetables from the garden, and turnips, potatoes, and cabbages from the fields. What we urgently needed was coffee. Not ersatz coffee, not Muggefugg, grain sludge—we needed the real thing.

My grandmother was mixed up in certain deals to obtain the beans and sugar we longed for. She had spun a plot with a character from the city who would show up at our place in a curious postwar contraption. Trade coffee for food? He wouldn’t take it, didn’t need it. Had plenty. It had to be something more refined, something special, something from us personally. A piece of our home.

A white billow in the distance. Who was producing all that steam? Who was that coming up here? A strange vehicle rolled nearer and nearer, until we discovered it was one of those do-it-yourself cars they called Holzgassers. It ran on steam rather than gasoline. In the back, on a platform behind the driver, sat a stove with a stovepipe and wood or coal heaped up next to it. When the power started to flag, the driver hopped out to top up the stove.

The cloud rolled over the bridge and curved into the courtyard. My grandmother pushed the curtain aside. Aha, there he is. She was already hurrying through the hallway. Just as the carriage stopped, with a creak of its hand brake, Grandmother stepped out the door.

Get out of the way! she said, annoyed, shoving the dog aside. Then, like a break in the clouds, a sweet smile flashed across her face.

So, what lovely surprises have you for us today, Mr. Breitreiter? she laughed in greeting.

Thus began the ritual. First, one acted as if the visit were a great surprise. But here only one thing really mattered: coffee, the delicacy that could not be found anywhere else. Grandmother’s eyelids fluttered. Her hands clapped, setting the mood: she stepped closer, leaned on the strange conveyance, folded her arms beneath her bosom, cocked her head, crossed one foot over the other. There she stood in the starting gate, all at once quite young again. The negotiations could begin.

Mr. Breitreiter had His Plan, how much coffee he was willing to leave in the house after his visit. My grandmother, too, had Her Plan. For there was never enough coffee. Uncertain when the spring would bubble forth again, she wanted to negotiate the most out of Breitreiter and titillated him with a baroque silver box, a Chinese snuff bottle. She did it so consummately that no one could see anything, skillfully holding the treasures in the folds of her skirts. If I was too eager to be part of it all, and came too close to her, she shooed me off. Go away, you cheeky devil! Grandmother had to concentrate.

My mother, too, stuck her head through the door and looked into the courtyard. In a single second her glance took in the whole space. Then, like the lens of a camera, her attention honed in on Breitreiter, vehicle, grandmother. My grandmother, for her part, paid no attention to my mother: Breitreiter was her turf.

Let’s go, my mother said to me, taking my hand. She pulled me through the house, down the stairs on the other side, and out into the garden.

Will we be getting more coffee? I asked.

Without a word my mother took two watering cans to the stream, bent deeply, plunged one can into the water as if she wanted to drown someone. When the gurgling tapered off, she jerked it back up, heavy with water, practically lost her balance, then repeated the whole process with the second can. She lugged both to the rose bed, her face red with exertion. I did not ask any more questions. I searched the roses for bugs, turned the petals over the way my mother had taught me to. Mother watered devotedly: here a bush, there a languishing shrub.

Eventually Breitreiter’s Holzgasser rattled off across the bridge, through the foliage. My mother looked up. A strand of hair clung to her moist brow. She sighed, trailing the cloud of dust with a dark frown, until the noise of the motor was lost in the vanishing point of the tree-lined avenue.

Later my mother noticed that a small patch had been cleared in the dust on the mahogany chest of drawers. A rectangle. That was the box. In the glass case, a dust-free oval. That was the snuff bottle. Once again Breitreiter had taken with him part of what my mother called “our culture.”

The war changed the value of all things. In the hour of need, intrinsic value seemed irrelevant, uprooted from its meaning. What was hard for one person to get was traded for what others could easily find. The value of the objects exchanged was unequal. Scarcity premium for scarcity premium. Everyone was more or less addicted to what they could not have. My grandmother was forgiven her bartering so long as times were bad. But when luxury goods were once again available on the open market, the family feuds began.

How on earth could my mother-in-law give that gouger all those superb, irreplaceable things? Adi lamented. He has enough of our estate to open an antique shop!

Over time, the family heirlooms—exquisite objects of ivory, part of the snuff bottle collection, fine small furniture, too—disappeared piece by piece into the Holzgasser. But in exchange we had real coffee, and my grandmother was in a better mood.

•

Sometimes as I sat with my grandfather, someone would say within my earshot: Yes, it’s quite true, quite obvious from the side. One can easily see it: she has the same profile.

What profile? I would ask.

Well, your nose and your bearing. Just like the Empress Sissi.

And what about this, they exclaimed: Beatrix is not even six, yet she is already binding up her waist!

Indeed, to the general amusement of our household, I was often seen with my smocked jumper tightly bound at the waist with one of my father’s cast-off red ties.

My grandfather, vintage 1860. His background was taboo.

Theodor Ost was the illegitimate child of Max of Bavaria, the king’s brother and Empress Sissi’s father. As an elderly gentleman Max had fallen in love with a beautiful maiden in Freising, where the royals went hunting. My grandfather was raised in Professor Zirngiebel’s house, where his mother worked. He attended the Maximilianeum with the children of the aristocracy, spoke ancient Greek and Latin, studied history, and became a professor. He had never known financial worries; he received a royal stipend. His suits were sewn by a Czechoslovakian tailor with fabrics from England; his shoes were made to measure in Italy. An air of mystery suffused his quiet existence. The backs of my grandparents’ wardrobes and chests of drawers, the undersides of chairs and table legs, all boasted the royal Bavarian coat of arms. Silver tableware was hidden in the finest pig-leather chests; the wondrously exotic collections showcased behind glass also came from Grandfather’s “family.” During the war years, the furniture had been evacuated to our house, along with my grandparents, to await the return of peace. In twilight, collectible objects stacked behind panes of glass were admired as a legacy. The furniture, too good to use, dozed away in the upstairs hall. These pieces were my grandmother’s domain. She dusted them, oiled the old woods, and forbade the children to touch them. She tied ornamental cords across the arms of the chairs so that no one would sit on them. A coverlet shielded the tabletop’s fine veneer. Only Grandmother could lift the cloth: at the base of the table, on a wooden stone, a boy played his flute at a wooden brook. I reached out to touch it with my finger.

Cut it out! she hissed. You look at valuable things only with your eyes, not your dirty fingers!