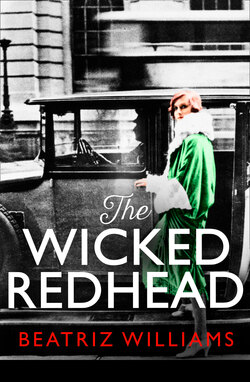

Читать книгу The Wicked Redhead - Beatriz Williams - Страница 6

ОглавлениеNew York City, April 1998

THE PHOTOGRAPH in Ella’s hand was about the size of a small, old-fashioned postcard. It had a matte finish, almost like newsprint, and the edges were soft and frayed, as you might expect from a photograph over seventy years old. From anything over seventy years old, really, but especially a photograph of a naked woman.

And what a woman.

She sloped along a Victorian chaise longue, wearing nothing but black stockings and ribbon garters, face turned upward to receive a fall of light from the sky. Miraculous breasts like large, white, dark-tipped balloons. Everything black and white, in fact, except her hair, which was carefully tinted red. Ella couldn’t stop staring at her. Nobody with a heartbeat could stop staring at that woman.

And it wasn’t her beauty that so transfixed you, because you couldn’t really see her face. It wasn’t even her incandescent figure, although that was the point of the photograph, wasn’t it? That figure. Ella couldn’t put a name to this mesmerizing force, except that it began somewhere beneath the milky skin of the woman herself and never really ended. You had the feeling that if you stared long enough, willed hard enough, she would turn her head toward you and say something fabulous. From the wall behind her hung a giant portrait, in which a painted version of the same woman languished on the same sofa, conveying all that sexual charisma in raw, awestruck, primitive brushstrokes. The title at the bottom said Redhead Beside Herself.

Ella turned on her side and traced the curve of the Redhead’s hip. No kidding, she thought. Her fingertips buzzed at the contact, but she was used to that, by now. On the bed beside her, Nellie lifted her head and growled softly, and Ella put out her other hand to soothe the dog’s ears.

“Nothing to worry about, honey,” she said. “Go back to sleep.”

But the dog kept growling at the same low, loose pitch, and the photograph buzzed even harder beneath Ella’s fingers, like a dial turning right, until Ella forced herself to look up and saw the hands of the clock on the bedside table.

She rolled to her back and stared at the ceiling.

“Damn,” she said. “It’s time.”

BEFORE SHE HEADED UPTOWN to the offices of Parkinson Peters to get fired, Ella dressed herself carefully in her best charcoal-gray suit and black calfskin pumps. Mumma used to say you should dress for your worst moments as if they were your best. Dad said to scuttle the ship with flags flying. Probably they meant the same thing.

After a fine, cool Sunday, the weather had turned damp overnight, and the smell of urine and vomit stuck to the air of the Christopher Street subway station. Ella sidestepped a puddle of spilled, milky coffee on her way to her spot—directly across the tracks from a peeling movie advertisement—and tried to breathe through her mouth. The film starred Jeff Bridges, looking even more scruffy than usual, locked in some kind of arabesque with an actress dressed in a gladiator outfit. Ella had spent the last month of mornings trying to decide whether the two of them were bowling or ice skating. The question was driving her slowly insane, and now, as she stared at the distant object in Jeff’s hands that might or might not be a bowling ball, she thought, At least I won’t have to stare at that fucking movie poster anymore. After this morning, she could stand somewhere else on the platform, instead of the particular spot that would put her on the subway car nearest the exit turnstiles at Fiftieth Street, and stare at some other advertisement.

The rails sang. The train roared softly down the tunnel. Burst like an avalanche into the station a moment later, rippling the coffee puddle, and Ella stepped on board and creased her Wall Street Journal into long, vertical folds that doubled back on each other, just as if this were any kind of regular morning, and she was headed for the office. The electronic bell rang its double tone. The doors thumped shut, found some obstacle, thumped again. The train jerked into motion, and Ella, staring at the blur of words in the newspaper column before her, realized that she had no idea what the name of that movie was. Maybe she never would.

At the Fourteenth Street station, the train filled with Brooklynites transferring from the 2 and 3 trains, and Ella, who was already standing, ended up shoved against one of the center poles, pretending to read her vertically folded Wall Street Journal in the alleyway between two thick male arms, belonging to two men in identical navy suits who were probably not going to get fired this morning.

Fired. Canned. Let go. Laid off, dismissed, discharged. Sacked, if you were British. Query: If Ella were working in the London office of Parkinson Peters, would she be sacked? Or could she demand to get fired instead? She refolded the paper to feign reading the second column and decided she would so demand, damn it. You had the right to get axed on your own terms. The train lurched for no reason. Squealed to a stop in the blackened tunnel between Eighteenth Street and Twenty-Third Street. The lights died. The whir of ventilation vanished, and the sudden stillness was like the end of the world. Nobody moved. The whole car just went on staring at its darkened newspapers, staring at the dermatology advertisements on the train walls, staring at ears and hats and backpacks and necks, staring at anything but someone else’s stare. Sweating palms on metal poles, submitting to the close-packed indignity of the New York subway. There was a garbled announcement, something about Penn Station. The car came to life, lights and noise and air, and lurched forward again. Ella fixed her gaze to her knuckles. Next to her, the man with the navy jacket sleeve made a slight movement and slipped his hand further up the pole, away from hers.

The train blew into Twenty-Third Street and stood on its brakes. Pitched Ella into the chest of the navy suit guy, who looked at her in horror.

Five more stops. Thirty city blocks between Ella and unemployment.

And her job was the least of her worries.

IN AN UNEMPLOYMENT TRIBUNAL, which God forbid, Parkinson Peters and its polished, navy-suited lawyers could probably make a reasonable case against Ella. You could always find actionable cause if you wanted to get rid of somebody, after all, and maybe Ella could have been more careful to make absolutely certain Travis Kemp—the managing partner on the Sterling Bates audit—knew that Ella’s husband happened to be employed at Sterling Bates, albeit in a wholly different division. She could have reminded Travis of the information on her disclosure form on file with human resources, instead of assuming he’d reviewed it before assigning her to the project. She could have used that opportunity to affirm that her husband, Patrick Gilbert, had no relationship, formal or otherwise, with the activities of the disgraced Sterling Bates municipal bond department, which Parkinson Peters had been hired to audit, and allowed Travis to decide whether Ella should remain on the team.

But none of those actions would have mattered, in the end. Ella’s dismissal had nothing to do with any kind of wrongdoing, at least on her part. She’d known that from the moment she hung up the phone with Travis on Friday evening, brimming with tears, brimming with all the physiological symptoms of shock. She was the kind of person who always paid for the apple she dropped in the supermarket instead of putting it back on the stack, who slipped a tip in the Starbucks box even when the barista wasn’t looking. She had tagged the unusual pattern of payments at Sterling Bates not because it was her job, but because it was the right thing to do.

Friday night, she’d shook with rage at the injustice of it all.

Not until later did she realize she had bigger things to worry about.

But she couldn’t think about that. She couldn’t think about Saturday night and she especially couldn’t think about Sunday afternoon, because the subway was really cooking now, congestion cleared up ahead, and by the time Ella had finished pretending to read the left two columns of the Wall Street Journal and started feigning the middle one, she was already crashing into Fiftieth Street, brakes squealing, mosaics blurring past, slowing, stilling. In the instant of silence before the doors opened, Ella nearly gagged on the smell of somebody’s sausage sandwich.

And then she was free. She burst out into the sour, damp underground and through the turnstiles, up the stairs, clutching her company laptop bag that contained a laptop scrubbed clean of files, clutching her Wall Street Journal in the other hand. She emerged into a chilly mist and checked her watch—seven thirty-nine, way too early, even for Ella—and ducked into a Starbucks to gather herself. Her hair was already curling into a hopeless cloud; she pulled an emergency scrunchie from the outside pocket of her bag and bound the mess back into a ponytail. Found her security pass and cell phone. Saw that she had missed two calls, one from Patrick and one from Hector, who had each called within a minute of the other. Hector had left a voice mail. Patrick, knowing better, had not.

Her husband and her lover. To be clear, her estranged husband and her brand-new lover, but did that matter in the eyes of God? Maybe it did, but waking up yesterday morning, she hadn’t felt a shred of guilt. Had instead felt bathed in something like God’s mercy, after six mortifying, agonizing weeks.

Now, as she stood before the pickup counter and accepted a latte she didn’t really want, Ella thought that maybe she was wrong. That she had bathed in nothing but sexual afterglow, and God was a vengeful God after all. Like Parkinson Peters, punishing her for a crime that belonged to somebody else.

BY ANY ABSOLUTE MEASURE, Ella had woken on Sunday morning in a state of sin. The waking was Nellie’s fault, the sin was all her own. Actually, the waking was probably Ella’s fault too, since responsibility for the dog’s bladder now belonged to her. She’d set aside Nellie’s wriggling, investigating body and squinted her eyes at the clock on the bedside table. Eleven minutes past nine. Also, there was a note.

Nellie lunged forward and licked Ella’s nose in frantic little strokes.

“All right, all right,” Ella had said. Sat up too fast and wobbled. Set her two hands on either side of her bottom and shook her head. Nellie climbed into her lap and stared beseechingly upward. Nothing more soulful than the round black eyes of a King Charles spaniel who needed to pee.

Across the room, the blinds were down over the windows, but the sunlight streaked fearlessly around the edges and illuminated what seemed like acres of Ella’s bare flesh. Full, happy breasts. Flushed, decadent skin. Curling, tumbled hair. Ella hadn’t examined her naked body in months, maybe even a year or two; she couldn’t even remember the last time she performed that ritual of minute, critical, inch-by-inch dissection of flaws, ending in resolve to eat less, exercise more, use moisturizer, buy another push-up bra, maybe reconsider a long-standing personal prohibition against cosmetic surgery. Back then—happily married—she hadn’t cared.

More recently—wronged wife—she hadn’t dared.

And now? Right that second? Staring down at breasts and stomach and thighs and calves and feet against the wrinkled, disgraceful white sheets? She’d thought she looked pretty damned beautiful.

Pretty damned beautiful. (That was Hector’s voice, echoing in her head.)

Hector. She reached for the note. Nellie barked and spun in a desperate circle.

“All right, all right,” Ella said again, retracting her hand, and this time she swung her legs over the edge of the bed and rose. The movement made her head slosh. Made her belly swim. Swamped her with the seasick, full-body hangover sensation of a night without sleep, except that unlike actual hangovers, or those following all-nighters spent at work, this malady represented a small price to pay for what had caused it. If you threatened Ella with a lifetime of such wakings, she wouldn’t trade away last night. If you erased her memory of the past twelve hours, she would still know it existed, humming in her bones and skin, shimmering down the long lines of her veins, hovering like a ghost inside her—

“I think I’m going to throw up,” she told Nellie, and exactly six seconds later she was leaning over the edge of Hector’s toilet bowl while Hector’s dog watched anxiously from the door.

After vomiting, she’d felt much better, the way you did. Weak but purged. Purged of what, she wasn’t sure. Guilt or sin or something, right? After all, she was married.

Except she didn’t feel guilty. She was quite sure of that. Ella knew what guilt felt like, and this wasn’t it. This was something more complicated, like when you walked onto an airplane headed to a brand-new country and couldn’t turn back, adventures waiting before you, and yet somewhere, in the back of your skull, pounded the certainty that you’d forgotten to pack something important. She found a washcloth on the counter and turned on the faucet and wondered whether her husband had barfed, the first time he cheated on her. Aunt Julie had said that Patrick was a congenital cheater; she could smell it on him, the way you smelled garlic on someone who had eaten forty-clove chicken the night before. He’d probably cheated in kindergarten. Kissing Michelle after telling Jennifer he was going to marry her. He was numb to sin. What was that line from Dangerous Liaisons? It only hurts the first time.

Well, Ella didn’t hurt at all, that Sunday morning. She didn’t regret a minute of the night before.

Nellie’s paws grabbed her knee. Bark ended in a whine.

“All right! All right!” Ella said, for the third time. She set down the washcloth and went back into the bedroom, Hector’s bedroom, Hector’s bed, Hector’s simple wooden furniture. On the chair lay her clothes, neatly folded, nowhere near where she had left them last night. In fact, Ella could have sworn she wore not a single stitch by the time Hector carried her from the living room to his bed, and yet here sat all those stitches, reconstituted, primly stacked, bra and panties on top, just as if they hadn’t spent the night strewn all over the living room floor.

This time, Ella didn’t bother deciding whether Patrick had or had not ever picked up her clothes from the floor after a night of passion. Didn’t think of Patrick at all, in fact, as she dressed herself in the clothes Hector had peeled off her body under a high, bright moon and then gathered together again, in the hour before dawn, while Ella lay absolutely expired under the down comforter. She pulled her hair back in the scrunchie Hector had also recovered from the floorboards. Nearby, Nellie chased her nonexistent tail in a kind of canine delirium. Ella slid on her shoes, tucked Hector’s note into her pocket, and called for Nellie to follow her into the living room.

By virtue of being related to the landlord, and also by virtue of his own skill at carpentry, Hector had the entire attic floor to himself: bedroom, bathroom, open living room and kitchen. The Sunday sunshine hurtled through the skylight to land in a scintillating rectangle on the kitchen counter, where Nellie’s leash and a plastic produce bag lay together with a bottle of water and a key. By now the dog was dancing on her claws. Yipping and begging. Ella leaned down and clipped the leash on her collar. Grabbed the bag and the water and the key as Nellie dragged her like a sled dog toward the door. Together, they raced along the flights of stairs, and Ella was out the vestibule and leaping down the stoop before she realized she hadn’t even looked at her own apartment door on the way down. How crazy was that? When that apartment had changed everything. The Redhead’s apartment, now hers.

Ella had to run to keep up with Nellie, who was making for a patch of gravel surrounding a tree near the corner, and her stiff muscles begged for mercy, like that time Ella’s sister Joanie had talked Ella into joining a Pilates class. And maybe she wasn’t quite that stiff this morning, not quite so aware of just how many muscles the human body could contain; maybe her soreness today was tempered by that sense of marvelous well-being set off by the joyful firecracker in her belly, the sensation she still couldn’t name.

But something else gnawed at her flesh—even when Nellie, after some investigation, decided on a spot and hunched down in relief—and Ella, resting at last, thought that maybe that gnawing came from her back pocket, where she’d stuffed Hector’s note as she flew out of Hector’s apartment. Moreover, she decided—shifting her balance, blowing on her fingers in the brisk air—the gnawing wasn’t because she missed him, although she did. She missed him the way you might miss a bone, if you woke up to find it missing from your arm or leg or rib cage. She missed kissing him and laying her hands on him in utter freedom, in the way they had finally done last night, the dam breaking at last under the pressure of Ella’s distress, but that wasn’t all; just being with Hector, just laughing with him and playing piano with him and lying on the floor staring through the skylight with him. She could live without the sex long before she could live without any of that.

She missed him, yes, she missed everything about him.

But the thing was—and Nellie was setting off again, full of purpose, and Ella had to force her legs to move—the thing was, when she woke up this morning, alone in Hector’s bed, she was kind of glad he wasn’t there.

And the note? Gnawing from the safety of her back pocket? She wasn’t in any hurry to read it.

HECTOR HAD LEFT TWO other voice mails on Ella’s cell phone, one Sunday afternoon around the time he must have landed in Los Angeles, and one in the evening. Both of them untouched, the same as Hector’s note, and just like Hector’s note the cell phone now went inside the front pocket of Ella’s laptop bag. She couldn’t listen to Hector’s voice right now, any more than she could look at Hector’s handwriting. He was probably frantic with worry, and still she couldn’t bring herself to hear those words, read those words, return his call and hear him speak more words. Not because she was guilty. Not because she didn’t care. Not because she didn’t long to hear Hector read the entire fucking Manhattan telephone directory in her ear, in the same way she longed to breathe.

Ella tried the latte. Too hot. She set it down and checked her watch—seven forty-eight—and decided she might as well get it over with. Lifted her laptop bag from the counter stool and walked out the door, forgetting all about the latte left on the counter until she was pushing her way through the glass revolving door of the Parkinson Peters building on Fifty-Second Street and Sixth Avenue and wondered why her right hand was so empty.

TO ELLA’S SURPRISE, HER security pass still worked. She spilled through the turnstile, in fact, because she’d been expecting it to stay locked. So maybe forgetting that latte was an act of mercy; it would have sloshed right up through the mouth hole and over her suit if she’d been holding it. What a disaster that would have been, right?

Fortunately, the lobby was still empty at this hour, and only the security guy noticed Ella’s misstep. Most of the Parkinson Peters staff wandered in around eight thirty, though you were expected to stay as late as it took, and certainly past six o’clock if you wanted a strong review at the end of the year. And that was just when you were on the beach, between assignments, performing rote work in the mother ship. (The cabana, if you didn’t want to mix your metaphors.) Ella crossed the marble floor like she owned it—that was the only way to walk, Mumma had taught her—and pressed the elevator button. While she waited, somebody joined her, and for an instant made eye contact in the reflection of the elevator doors. A woman Ella didn’t recognize, dressed in a charcoal-gray suit similar to hers. Nice suit, Ella wanted to say, a final act of transgression while she still had the chance. But of course she didn’t say it. There was no point. Ella thought she had a finite amount of rebellion inside her, which she had used up considerably on Saturday night, and she didn’t want to waste any of the remainder. Unless rebellion was the kind of thing that fed on itself. Unless breaking the minor code of elevator silence—they had boarded the car by now, rushing upward to the thirty-first floor, where Ella was shortly to be made an ex-employee of Parkinson Peters—unless committing that misdemeanor gave her the courage to break other, larger rules, a courage that she was shortly going to need in spades. In which case—

But it was too late. The elevator stopped at the twenty-fourth floor and the woman and her suit departed forever. Ella continued on to the thirty-first floor and unlocked the glass door to the Parkinson Peters offices with her pass. Strode to an empty cubicle, dropped her bag by the chair, went to the kitchen, and poured herself a cup of coffee to replace the one she had left behind at Starbucks. The room was in the center of the building and had no windows. The fluorescent light cast a sickly, anodyne glow, so that even the new granite countertops looked cheap. Ella was stirring in cream when an apologetic voice called her name from the door. She turned swiftly, spilling the coffee on her hand.

“Ella? I’m so sorry.” It was Travis’s assistant, Rainbow, crisp and corporate in her Ann Taylor suit and cream blouse. Ella always imagined a pair of hippie parents serving her Tofurky at Thanksgiving and wondering where they had gone wrong. “Mr. Kemp asked me to send you to his office as soon as you came in.”

Ella turned to reach for a paper towel. “I’ll be just a minute, thanks.”

She took her time. Cleaned up the spill and washed her hands. Stuck a plastic lid on the coffee cup and took it to her desk, so she could drink it later. Her hand, carrying the coffee, setting it down on the Formica surface, remained steady. The nausea had passed. She unzipped her laptop bag and took out a leather portfolio, a yellow legal pad, and the Cross pen she used for business meetings, the one her father had given her when she first landed the job at Parkinson Peters, and as she walked down the passageway between the cubicles, it seemed to her that she could hear his proud voice as he gave it to her, Ella, his firstborn. Use it for good, he’d said, wagging the box. There’s power in this.

She reached Travis’s office, which was not on the corner but two offices down—he’d only made partner a few years ago—and knocked on the door.

“It’s open,” said Travis, in a voice that was neither stern nor angry, and in fact sounded as if he’d just been sharing a joke.

So Ella pushed the door open and discovered she was right. He had been sharing a joke—or at least some pleasant morning banter—with a muscular man sitting confidently in the chair before the desk.

Ella’s husband.

Before she even comprehended that it was Patrick, before her eyes connected with her brain and lit the red warning light, he was bounding up from the chair and kissing her cheek. “Well, hello there, Ella,” he said, just as if they’d woken up in bed together this morning, as if he still owned the right to her kisses.

“Patrick? What the hell are you doing here?”

There was a brief, nervous pause. Patrick took a step back and laughed awkwardly. Ella looked from him to Travis, Travis looked from her to Patrick. He was jiggling a pen in his left hand, and an artsy, black-and-white photograph of his family smiled over his shoulder. The sight of it, for some reason, maybe its black-and-whiteness, made Ella think of Redhead Beside Herself. She turned back to Patrick and said, Well?

He tried to lay an arm around her shoulders, but she edged to the side.

“I’m here for you, babe,” he said. “I heard what happened on Friday.”

“How? Who told you?”

He shrugged. He was smiling—Patrick had one of those room-lighting smiles, it was part of his arsenal—and Ella realized he wasn’t wearing a suit. Just a pair of chinos and a navy cashmere sweater over a button-down shirt of French blue. He looked like he was off to race yachts or something.

“Just heard from someone at work,” he said. “I tried to call you this weekend, but you weren’t answering. So I came down here this morning to see my man Kemp and explain.”

Travis had turned his attention to some papers on his desk during this exchange, making notes in his quick, tiny handwriting that had always confounded Ella. But she could see that his ears were wide open. His neck was a little flushed above his white collar. He was going to tell his wife all about this tonight.

Ella folded her arms. “Explain what?”

“I quit my job,” Patrick said.

“You what?”

“I quit. Tendered my resignation over the weekend.”

“This is a joke, right?”

Patrick shook his head. Still smiling. “Nope. I figured if one of us had to take a fall, it should be me. You didn’t do anything wrong.”

“Neither did you.”

“Well, then call me a gentleman.”

“Ella,” said Travis, looking up from his papers, “I got your husband’s email over the weekend and discussed the matter on the partner call this morning, and we’ve agreed to keep you on at Parkinson Peters. You’ll be moved to a different project—”

“No,” she said.

If she’d taken a pistol from her pocket and fired a bullet through the window, the two men would probably have been less startled. The pen dropped from Travis’s hand and smacked on the desk.

“No, what? No, you want to stay on the Sterling Bates audit? I’m afraid—”

“I mean, no, I don’t want to stay at all.” Ella opened up her leather portfolio and removed a sheet of paper. Set it on the desk in front of her, edges exactly straight. “My resignation letter.”

“Jesus,” said Patrick.

Travis stared at the letter and said, Well.

Ella snapped the portfolio shut. “So that’s that. I’ll stop by HR with a copy for them—”

“Can I ask where you’re going?” Travis said, looking up from the letter. He gathered up the pen and started clicking the end. His eyes were bright and narrow. “Who’s recruited you? Deloitte?”

“No one.”

“You’re not moving somewhere else?”

“No.”

Travis sat back in his chair, still clicking the pen. He bounced a few times, causing the chair to squeak. His window faced east, and the gray sun balanced at the back of his head. Between the buildings, where Queens should be, there was nothing but cloud. His lips stretched into a smile.

“Can I ask what you’re planning to do?” he said, in a tone of absolute pity.

Ella returned her portfolio under her arm and smiled back. “Nope,” she said, and walked out the door, right past her dumbstruck husband.

BUT PATRICK NEVER STAYED dumbstruck. He always had something to say. He chased her down the corridor of cubicles and caught up when she reached the one she’d claimed with her suit jacket.

“Ella,” he said, “wait.”

“I have nothing to say to you.”

“Did you get my flowers?”

She turned. “First of all, how did you get my address? From my family?”

“No.” He hesitated. “From Kemp.”

“Oh my God. How illegal is that?”

“We’re still married, Ella. I have the right to know where you’re living.”

“And I have the right to get a restraining order, if I need to.”

He took her elbow and spoke in a low, heartfelt voice. “Don’t. It doesn’t need to be like this. Come home, Ella, please. I mean, seriously. You left our place for some shithole in the Village?”

“I left you because you were cheating on me, and it’s not a shithole. It’s—” She stopped herself before she said magical. “It’s a special building.”

“It’s a dump. You can’t live there. It doesn’t even look safe.”

Ella removed his hand from her elbow and reached for her suit jacket. “It’s the safest place I’ve ever lived, and I’m not moving anywhere, especially not with you.”

“For God’s sake, Ella. I just quit my job for you! Managing director at Sterling Bates, and I threw it all away just to prove to you—”

“Look. I don’t know the real reason you quit the bank, Patrick, but I’m pretty sure I wasn’t it. This conversation is over. You’ll be hearing from my lawyer pretty soon. As they say.” She dodged his reaching hands and slung her laptop bag over her shoulder. Headed for the elevators, followed by every pair of eyes on the floor, and she didn’t care! Maybe a little, but not really. Didn’t care, for once, that everyone in the office had just heard the soap opera that was Ella Gilbert’s life. That her husband had cheated on her—too bad she had no time to rehash for them the full story, the visceral details, the grunting-sweating-banging of an orange-skinned hooker in the stairwell of their own apartment building—and that, as a result, Ella was divorcing him. Omigod, poor Ella, did you hear? She passed Rainbow, whose awed eyes followed her all the way to the glass doors, while Patrick followed, saying something, some blur of words.

As she found the door handle, Patrick reached out to cover her hand.

“Ella, you can’t just cut me out of your life,” he said in her ear.

She stared at Patrick’s hand, his left hand. The gold wedding band that circled his ring finger, engraved on the inside (she knew this because she had ordered it herself, picked out the Roman lettering as both traditional and masculine) EVD TO PJG, 6*13*96. He had nearly lost it on their honeymoon. Nearly lost it while they were swimming together off some beach in Capri, because a ring was such a new, unfamiliar object to him, and he kept jiggling it on his finger like a toy hoop. Off it came. He was distraught. Dove for it, again and again, even though Ella begged him to stop because each time he plunged under the water and the seconds ticked by, panic took hold of her stomach. Then he came up at last, triumphant, brandishing the plain gold band between his thumb and forefinger like he’d recovered some pirate’s diamond from the seabed. Salt water dripping from his skin. He handed Ella the ring and made her put it back on his finger, right there in the chest-deep water, and she did as he asked, wiggling it all the way down to his knuckle. He’d snaked his arms around her waist. “That’s the last time,” he said, when he was done kissing her, which took some time. “It’s never coming off again. You’ll have to bury me with that ring on my finger.”

And now, here they were. Ella stared down at the shining band that reflected the fluorescent office lights, at his big hand covering hers, and she remembered thinking, in the sunlit moment while she kissed Patrick on that beach, how lucky she was. How lucky she was to have found a man who loved her so much.

With her own left hand, which contained neither engagement ring nor wedding band, she plucked Patrick’s fingers away.

“Honestly, Patrick?” she said softly. “I don’t think we have anything left to say to each other.”

A QUARTER OF AN hour later, Ella pondered this lie as she sat on a Starbucks stool, drinking a fresh latte to replace the one she’d left behind earlier. Her phone buzzed from her laptop bag. She waited for the buzzing to stop, waited for another minute or two after that, and then she tilted the bag toward her and plucked the phone free. Hector again. She put her fingers to her temple and stared at the screen, Hector’s name—just that single word, Hector, formed of tiny green LED lights, followed by his phone number—until it blinked out. Until her ribs ached. Until the joints of her fingers turned white, she was gripping the phone so hard.

She put it back in her bag and took out the note.

You have to face him sometime, Dommerich, she told herself. (She was now addressing herself by her maiden name again—that was something, right?) If she couldn’t yet trust herself to listen to his recorded voice, to God forbid speak to him, she could at least do him the courtesy of reading the note he’d left behind for her, when he slipped out yesterday before dawn and caught his flight to L.A. The flight he’d already rescheduled in order to spend Saturday night in bed with her.

Ella. Think I’m supposed to wake you up and say good-bye right now, but it might kill me. [There was a clumsy drawing of an arrow and a heart, with you written next to the arrow, and me written next to the heart.] Stay here, sleep in my bed, drink all my booze, play my piano, listen to my band watching over you. Think of everything we have left to do. Don’t be afraid. Back soon. H.

Back soon.

Today was Monday; Hector would return to New York on Saturday. On Saturday morning he was going to come bounding through the door, he was going to call her name anxiously, he was going to scoop her up and demand to know why she hadn’t returned his calls, hadn’t picked up the phone, hadn’t let him know she was okay, that she loved his apartment, she loved Saturday night, she loved him like he loved her.

What was she going to say?

Don’t be afraid, he wrote. My band watching over you.

But Hector had it wrong. She was afraid, yes, but she wasn’t afraid of the band playing inside the apartment building on Christopher Street. They had kept her company Sunday night, when she had buried herself under the covers of Hector’s bed and wrapped her arms around her stomach and cried. The clarinet had played her something beautiful and comforting, until she loved that clarinet almost as much as she loved Hector himself. Then, as now, she had taken out the photograph of Redhead Beside Herself and stared at that image, that naked, wicked woman who had inhabited those walls over seventy years ago, and the sight of her—just as it did now—dried up Ella’s eyes and her despair.

Don’t be a ninny, the Redhead told her. I got no time for ninnies. You got yourself in trouble, you go out there and figure out how to fix it. You go figure out what to do with yourself. Just go out there and live, sister. Live.

Ella slipped the note and the photograph back into her laptop bag. Gathered herself up and walked out of Starbucks to start looking for her.

For the Redhead, whoever she was.

Wherever she was.