Читать книгу Inflection 06: Originals - Beatriz Colomina - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеEDITORIAL

Anna Petrou, Brittany Weidemann and Harrison Brooks

In design and architecture, the elusive attribute of original is continually sought after, and often viewed as a marker of success. Inflection vol. 6: Originals explores the contentious notion of originality and authorship in an increasingly digital society. How can architects and designers redefine their relationship with originality to enrich and inform their work?

A preoccupation with originality has become ubiquitous in the design fields; however, historically, this has not always been the case. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, architecture was created from a catalogue of formalised techniques, associated with Classicism and Gothic. The advent of Modern Architecture in the 20th-century heralded a shift and originality became an essential constituent of ‘good design.’ Throughout the 20th-century, architects accepted this idea as fundamental. Contemporary technology, however, has disrupted these assumptions. As replication and copying become ever more commonplace due to emerging digital techniques and production, originality becomes ultimately meaningless.

Much of the work in vol. 6 is indebted to the writing of theorist Walter Benjamin. His text The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction noted the significant impact that technologies of reproduction have on art and culture.1 Benjamin’s theory continues to be affirmed as digital reproduction becomes increasingly accessible and normalised. Philosopher Jean Beaudrillard expanded upon Benjamin’s theory in his seminal work Simulacra and Simulation. This book informs authors, artists and architects as they grapple with the proliferation of digital imagery in society today.2 Deniz Balik Lokce introduces the theories of both Benjamin and Beaudrillard. Focusing on the work of architectural firm BIG, she explains how mechanical reproduction results in simulacra and simulation as design work is cast adrift from its original context.

The phenomenon of Chinese copycat cities is critiqued by Betsabea Bussi and Zeynep Tulumen. The authors analyse the nature of ‘simulacrascapes;’ cities that begin as copies but over time develop their unique characteristics that reflect local environments. These copycat cities reveal the tension between what may be deemed true originals or replicas. While our relationship with originality is fraught with tension, Hannah Wood and Olympia Nouska are optimistic that the development of digital fabrication technology is reconnecting the architect with the act of making. Although this technology can ostensibly be used to create copies, it also allows for the easy construction of bespoke elements and architectural solutions.

Copying can also be leveraged as a representational technique in the form of collage, as described in John Paul Rysavy and Jonathan Scelsa’s piece, ‘Still Lifelike.’ Rysavy and Scelsa understand that the contingency of objects placed on a field generate a dialectic between the given objects and thereby form commentary. The ability to collage objects that could never exist together in the physical world is unique to collage as a creative medium. Through art, we can create new realities. On deeper inspection, our contemporary understanding of originality is closely engaged with an understanding of what constitutes reality. The value of manufactured or ‘fake’ images is that they describe realities that surpass the merely physical. Anna Kilpatrick’s thesis project, ‘Unfinished Palazzo,’ demonstrates a reality constructed of history and culture as she delves into the heritage of Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, a building that was never completed.

If architecture is composed of more than merely physical elements, original theoretical sources are essential to architectural production. In X-Ray Architecture, Beatriz Colomina reframes Modernism through the lens of illness.3

In conversation with Inflection editors, Colomina discusses the importance of interrogating original sources rather than accepting conventional readings.

In our global society, technology has inevitably unhinged architecture from its context. Architectural imagery is disseminated with ease online and through print media. Sean Godsell is wary of an increasing homogeneity in architecture and describes instead an architecture that is sensitive to the history and landscape of Australia. While he acknowledges the importance of references and sources, he also warns of the dangers of referencing types and forms that bear no relevance to their context.

Mixed Reality technology offers the possibility of an entirely immersive type of copying as virtual worlds and visualisations are created. In Dominic On’s piece, ‘A Point Cloud Darkly,’ we are introduced to a speculative future where the image and experience of Hong Kong is heavily augmented through digital technology. While the digital landscape may be used as an apparatus of repression, On also offers the optimistic prospect of resistance through community-led construction of alternative virtual spaces.

As we shape our public space through Mixed Reality technology, we also shape our bodies and personal identities. Adam Peacock’s work elucidates that technology is changing our culture without critical intention. As we manipulate our self-image through digital technology, physical manipulation through medical and genetic intervention is becoming ever more accessible. Rather than letting the possibilities of technology shape our cultural dialogue, Peacock uses speculative design to critique and hopefully shape our social future. In contrast to speculative futures, current architecture and design is saturated with reproduction, copying and referencing. To look back is unavoidable, but it must be undertaken with care. Lachlan Welsh’s piece, ‘HyperStyle,’ critiques ‘paper-thin’ stylistic referencing and endorses a more critical reading of the past.

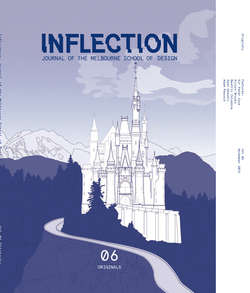

By nature, architectural publications can only describe architecture in a two-dimensional manner. By creating images of buildings, vast swaths of the information held by three-dimensional lived and experienced objects are inevitably lost. The cover of vol. 6 expresses this conflict by depicting a well-known image—the fantasy castle. This type of castle is an embodiment of simulacrum, perpetuated by constant retelling in culture. The silhouette of a Disney castle is modified with architectural references, transposed onto a partially fictionalised Germanic landscape, in reference to Neuschwanstein Castle and the landscape of fairytale. The content of Inflection vol. 6 reveals that architecture and design is unavoidably entrenched in context. Through critical engagement with notions of originality, architects and designers can begin to produce work that is distinct, intelligent and provocative.

01Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken, 1969.)

02Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. S. F. Glaser (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1994).

03Beatriz Colomina, X-Ray Architecture (Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2019).