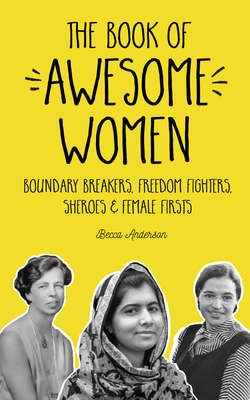

Читать книгу The Book of Awesome Women - Becca Anderson - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление• Foreword •

The Book of Awesome Women provokes a question I’ve asked myself dozens of times: Where was this treasure—house of a book when I went to school? From the first grade on, I sat at my desk, listlessly listening to the cliched tales of heroes from history, all of them—or so it seemed—male. Meanwhile, as I grew up in the Pacific Northwest of the fifties, many of the women profiled in this book were busy making history, making changes, making intellectual contributions, and making waves. Did I hear about any of them in school? In the media? On that shiny new world of communications called television? Rarely, if ever.

Would my life have been different if I’d had these daring examples to aspire to, to take courage from, to lean on as my own personal support group from history? Most definitely.

For instance, when my mother and father pushed me toward a particular college, I asked what they saw me doing with my education, and they said, “A nurse, perhaps. Or a teacher.” I turned angrily from their narrow vision and their well-meant path of higher education. It was decades before I saw the learning (as valid when enrolled in the university life as well as in more traditional institutions) would set me free, free to become whatever I set my mind to be.

Over the years, as I made my way as a writer and researcher, many of the sheroes in this book became my personal sheroes, too. The lives and deeds of women like Mary Leakey, Karen Silkwood, Margaret Mead, Rachel Carson, and Eleanor Roosevelt moved me deeply and helped me grow. As a thirtysomething college reporter, for instance, I got to write my first news story about Billie Jean King’s rout of Bobby Riggs—and in so doing, the sheer audacity of Billie Jean’s actions struck home. The Book of Awesome Women brings all of my favorite women, and hundreds more, to luminous life—a brilliant and encyclopedic achievement for one book.

Of late, I’ve been thinking a lot about just how and why the jigsaw of our whole human history came to have so many female pieces missing. Since 1995, the publication date of Uppity Women of Ancient Times, my first book about real-life female achievements of long ago, I have given hundreds of lectures, workshops, and talks to audiences about the frisky, risk-it-all women from our ancient, medieval, and Renaissance past. I point out that many of these trailblazers were famous—or infamous—in their own day. Invariably, someone in the audience asks: “If these women were household words, how and why did they become invisible?”

At this point, I mention a trio of female names and say: “What do these names mean to you?” After having given this pop quiz to several thousand people now (many of them well-read women whose educations far exceed my own), I regret to say that no one has known the answers. No one. Not one person has identified three key women who I selected at random from our own, very recent American history.

This response—or lack of one—leads me to my most telling point. “You see? Even in the late twentieth century, the historical invisibility process often begins immediately—in a woman’s own lifetime.”

The Book of Awesome Women, is a perfect antidote to that process, a bold and colorful portrait of women who dared to pursue their dreams. In that pursuit, they themselves become raw material, the idea matrix for other women’s dreams. They become, in a word, sheroes—a word, and a notion, whose constituency is going to grow ever more clamorous in the brave new second millennium.

—Vicki Leon, author of the Uppity Women in history series, published by Conari Press.

P.S. Take my “invisible women” quiz yourself and see how well you do. Identify the following twentieth century women: Junko Tabei, Sally Louisa Tompkins, and Gerti Cori.

Answers: Junko Tabei—first woman to climb Mount Everest, on May 16, 1975. This housewife led an all-woman Japanese team to the top. Sally Louisa Tompkins—only woman to be named an officer in the Confederate Army, where she ran the hospital she’d already established (at her own expense) with the lowest mortality rate of any soldier’s hospital in the South. Gerti Cori—first female doctor to win a Nobel prize; awarded in physiology and medicine in 1947 and shared with her husband.