Читать книгу One Night Wilderness: Portland - Becky Ohlsen - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

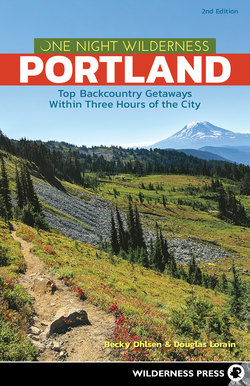

ОглавлениеEpic views like this one of Mount Hood, from Trip 42, Lookout Mountain and Oval Lake, are more accessible than you might think.

Introduction

It’s a busy world out there. Ask anyone you meet how they’re doing, and chances are that’s what they’ll say: “Busy!” Little old Portland is growing and changing; the pace of life here is not as mellow as it used to be. Despite being surrounded by natural wonders, most of us spend our days looking at screens, checking tweets and emails around the clock, and then when it’s finally time to relax, we’re too tired to do much more than sink into the couch and stare at another screen.

Which makes escaping into nature more important than ever. There’s a good reason “forest bathing” has become a trend, even if many of us roll our eyes at the term. Studies have shown that just 5 minutes in nature can transform your body and mind, making you more relaxed, more creative, smarter, and happier overall. It’s good for the brain, it’s good for the soul, and it’s even good for our social media profiles, in the long run. We know we need it.

But it can be hard to find the time to get away. That’s the beauty of this book: you don’t have to find much time at all. A single overnight excursion into the backcountry can have a huge impact, and these trips are all within a few hours’ drive of the city. Some are ideal for getting short blasts of nature, a quick booster shot. They involve hikes of just a mile or two, which means you could conceivably pack up on a Friday after work, hustle out to the trailhead, and be sipping hot cocoa and gazing at stars that same night. Imagine waking up on Saturday morning, peeking through the tent flap at mist on a lake, and sipping your morning coffee from a sleeping bag—with no laptop in sight.

And if a quick, one-night trip is good, a longer trip is even better. I say this from experience: nothing realigns your perspective quite like scrambling up the rocky side of a valley scooped out by glaciers and cresting the rim to see glittering Mount Adams, right there, almost close enough to touch. Add to that a picnic lunch beside an iridescent turquoise lake, a campsite that feels like some kind of hover pad floating in a cloud city, and a gentle stroll the next day through some of the most enchanting alpine valleys in the Pacific Northwest. Stress? What stress? You can find all this, by the way, on the Snowgrass Flat Loop hike.

You could do many of these trips as day hikes, especially if you get to the trailhead early in the day. But there’s something about spending the night—maybe because carrying everything you need makes you feel tough and self-reliant—that adds immeasurably to the experience. The Portland area is rich with writers who love the outdoors, so there are dozens of excellent guides to day hikes in the area. There are also several good volumes on extended backpacking trips, the kind you plan and prepare for months to pull off. I’ve been lucky enough to work on one of those guides too. But this book strikes the perfect balance between the two: a hand-picked range of accessible hikes, often kid-friendly and requiring minimal time commitment, that also gives you backpacker-friendly details like where to find the best campsites and water sources, what permits and regulations apply, and the best way to get to the trailhead.

It’s true we’re all busy—but there’s a good reason we live in this fantastic place, where the outdoors is so easily within reach. I hope you’ll take time to enjoy it, and if you’re so inclined, send me a note about your trip at bohlsen@gmail.com.

Tips on Backpacking in the Pacific Northwest

Although this is more of a where-to than a how-to guide, it may be helpful, especially for those new to our area, to cover a few basic tips and ideas specific to backcountry travel in the Pacific Northwest.

GET THE RIGHT PERMITS Most national forests in our region require that a Northwest Forest Pass be displayed in the window of all vehicles parked within 0.25 mile of any major, developed trailhead. Isolated trailheads with minimal or no facilities are generally exempt. In 2019 daily permits were $5 and an annual pass was $30. The annual passes are available at ranger stations and at many local sporting goods stores, or they can be purchased online at discovernw.org (click on “Store”).

CHECK THE SNOWPACK The winter snowpack has a significant effect, not only on when a trail opens, but also on wildflower blooming times, peak stream flows, and how long seasonal water sources will be available. It’s a good idea to check the snowpack on or about April 1 (the usual seasonal maximum), and make a note of how it compares to normal. This information is available online at nrcs.usda.gov (click on “State Websites” and navigate to Oregon or Washington). If the snowpack is significantly above or below average, adjust the trip’s seasonal recommendations accordingly.

WATCH OUT FOR LOGGING TRUCKS When driving on forest roads in our area, keep an eye out for logging trucks, especially on weekdays. These scary behemoths often barrel along with little regard for those annoying speed bumps known as passenger cars.

CHECK TRAIL CONDITIONS The Northwest’s frequently severe winter storms create annual problems for trail crews. Occasionally trails are washed out for years, but at a minimum, early-season hikers should expect to crawl over deadfall and search for routes around slides and flooded riverside trails. Depending on current funding and the trail’s popularity, maintenance may not be completed until several weeks after a trail is snow-free and officially open. Unfortunately, this means that trail maintenance is often done well after the optimal time to visit. On the positive side, trails are usually less crowded before the maintenance has been completed.

LEAF IT, DON’T LEAVE IT For environmentally conscious backpackers, one good solution to the old problem of how to dispose of toilet paper is to find a natural alternative. Two excellent options are the large, soft leaves of thimbleberry at lower elevations, and the light-green lichen that hangs from trees at higher elevations. They’re not exactly Charmin soft, but they get the job done.

WARN HUNTERS YOU’RE NOT A DEER General deer-hunting season in Oregon and Washington runs from late September to early November. For safety, anyone planning to travel on national or state forest land during these periods (particularly those doing any cross-country travel) should carry and wear a bright red or orange cap, vest, pack, or other conspicuous article of clothing. Hunting is generally not allowed in state or national parks (apart from some very limited and specific exceptions for waterfowl), so this precaution does not apply to those areas.

YOU’RE NOT AN ELK, EITHER Along the same lines as the above, elk-hunting season is generally held in late October or early November. The exact season varies in different parts of each state.

BE CAREFUL WITH FUNGI Mushrooms are a Northwest backcountry delicacy. Although our damp climate makes it possible to find mushrooms in any season, late August–November is usually best. Where and when the mushrooms can be found varies with elevation, precipitation, and other factors. In some places, you’re not allowed to take anything out of the forest without a permit; if you do find any fungi, be sure it’s OK to collect them for personal use. Also make absolutely sure that you know your fungi. There are several poisonous species of mushrooms in our forests, and every year people become ill or even die when they make a mistake in identification.

BRING THE BEATER Sadly, car break-ins and vandalism are regular occurrences at trailheads. This is especially true at popular trailheads and a particular problem for backpackers who leave their vehicles unattended overnight. Thus, hikers need to take reasonable precautions. Do not encourage the criminals by providing unnecessary temptation. Preferably, leave the new car at home and drive to the trailhead in an older vehicle. Even more important, leave nothing of value inside, especially not in plain sight.

Safety

While backpacking is not an inherently dangerous sport, there are certain risks you take anytime you venture away from the comforts of civilization. The trips in this book go through remote wilderness terrain. In an emergency, medical supplies and facilities will not be immediately available. The fact that a hike is described in this book does not guarantee that it will be safe for you. Hikers must be properly equipped and in adequate physical condition to handle a given trail. Because trail conditions, weather, and hiker ability all vary considerably, the author and the publisher cannot assume responsibility for anyone’s safety. Use plenty of common sense and a realistic appraisal of your abilities, and you will be able to enjoy these trips safely.

Spectacular scenery makes the Snowgrass Flat Loop (Trip 11) extremely popular.

The following section outlines the common hazards encountered in the Portland area outdoors and discusses how to approach them.

Plant Hazards

POISON OAK If you recognize only one plant in the Pacific Northwest, it should probably be this one, which grows as a low-lying shrub or bush. Its glossy, oaklike leaves grow in clusters of three and turn bright red in the fall before dropping off in the winter. The leaves and stems contain an oil (urushiol) that causes a strong allergic reaction in most people, creating a long-lived, maddeningly itchy rash where the oil contacts the skin. Wash skin thoroughly with soap and water as soon as possible, and clean any clothing and pets that may have come into contact with the plant as well.

poison oak

Photo by Jane Huber

Animal Hazards

BEARS Black bears are found throughout Oregon and Washington. If you encounter one, stay calm, avoid eye contact, and back away slowly. In areas known to have bears, use the food storage boxes provided at campgrounds, and carry your food and any other scented items in bear canisters.

MOUNTAIN LIONS Although these large felines are still rarely seen and pose minimal threat, reported sightings in Oregon and Washington have recently increased as population growth has caused cougar habitat to shift gradually into more urban areas. In 2018 a cougar was suspected of having killed a hiker on Mount Hood, marking the first-ever fatal mountain lion attack in Oregon history. If you do encounter an aggressive mountain lion, stay calm, maintain eye contact, make yourself look as large as possible, and do not run away. If you have children with you, pick them up.

RACCOONS AND MICE While not a threat to humans, these scavengers have learned that campgrounds and trail camps are prime locations for free meals. They are a major hazard for food supplies. Never leave your food unattended, and always store it somewhere safe at night—ideally hanging in a critter-proof bag from a nearby tree. Food lockers are provided at many trail camps.

RATTLESNAKES Common in high-desert environments, these venomous creatures like to bask on hot rocks in the sun and typically begin to emerge from winter hibernation as temperatures warm in spring. They usually flee at the first sight of people and will attack only if threatened. Be wary when hiking off-trail, and don’t put your hands where you can’t see them when scrambling on rocky slopes. Rattlesnake bites are rarely fatal. If you are bitten, the goal is to reduce the rate at which the poison circulates through your body: Try to remain calm, keep the bite site below the level of your heart, remove any constricting items (rings, watches) from the soon-to-be-swollen extremity, and do not apply ice or chemical cold to the bite, as this can cause further damage to the surrounding tissue. Seek medical attention as quickly as possible.

Northern Pacific rattlesnake

Photo by Jane Huber

TICKS These parasites are common in areas of scrub oak (such as along the Columbia River Gorge and the Rogue River in Oregon) and the forests of western Washington, especially during early spring. Always perform regular body checks when hiking through tick country. If you find a tick attached to you, do not try to pull it out with your fingers or to pinch the body; doing so can increase the risk of infection. Using tweezers, gently pull the tick out by lifting upward from the base of the body where it is attached to your skin. Pull straight out until the tick releases, and do not twist or jerk, as this may break off the mouthparts under your skin. Treat any tick bite by washing the area with soap and water, disinfecting it, and keeping it clean to prevent infection.

Ticks are known for transmitting Lyme disease, but cases of Lyme in Oregon and Washington are relatively uncommon. Even if you are bitten, an infected tick must be attached for 24 hours to transmit the disease. Lyme disease can be life-threatening if not diagnosed in its early phases. Common early symptoms include fatigue, chills and fever, headache, muscle and joint pain, swollen lymph nodes, and a blotchy skin rash that clears centrally to produce a characteristic bull’s-eye shape 3–30 days after exposure. If you fear that you have been exposed to Lyme disease, consult a doctor immediately.

Physical Dangers

GIARDIA Giardia lamblia is a microscopic organism found in many backcountry water sources. Existing as a dormant cyst while in the water, it develops in the gastrointestinal tract upon consumption and can cause diarrhea, excessive flatulence, foul-smelling excrement, nausea, fatigue, and abdominal cramps. All water taken from the backcountry, even if it looks perfectly clear, should be purified with a filter, with a chemical treatment, or by boiling it for 3 minutes.

HEATSTROKE Heatstroke (hyperthermia) occurs when the body is unable to control its internal temperature and overheats. Usually brought on by excessive exposure to the sun and accompanying dehydration, symptoms include cramping, headache, and mental confusion. Treatment entails rapid, aggressive cooling of the body through whatever means available—cooling the head and torso is most important. Stay hydrated and have some type of sun protection for your head if you expect to travel along a hot, exposed section of trail.

HYPOTHERMIA The opposite of heatstroke, this life-threatening condition occurs when the body is unable to stay adequately warm and its core temperature begins to drop. Initial symptoms include uncontrollable shivering, mental confusion, slurred speech, and weakness. Cold, wet weather poses the greatest hazard as wet clothes conduct heat away from the body much faster than dry layers. Fatigue reduces the body’s ability to produce its own heat, and wind poses an increased risk as it can quickly strip away warmth. Immediate treatment is critical. Raise the body’s core temperature as fast as possible. Get out of the wind, take off wet clothes, drink warm beverages, eat simple energy foods, and take shelter in a warm tent or sleeping bag. Do not drink alcohol, as this dilates the blood vessels and causes increased heat loss.

Taking Precautions

LEAVE AN ITINERARY Always tell someone where you are hiking and when you expect to return. Friends, family, rangers, and visitor centers are all valuable resources that can save you from a backcountry disaster if you fail to reappear on time.

KNOW YOUR LIMITS Don’t undertake a hike that exceeds your physical fitness or outdoor abilities.

AVOID HIKING ALONE A hiking partner can provide the buffer between life and death in the event of a serious backcountry mishap.

BRING THE RIGHT GEAR Packing the proper equipment, especially survival and first aid supplies, increases your margin of safety.

The 10 Essentials

Except when hiking on gentle trails in city parks, hikers should always carry a pack with certain essential items. The standard “10 Essentials” have evolved from a list of individual items to functional systems that will help keep you alive and reasonably comfortable in emergency situations:

1. Emergency shelter: a tent, a bivy sack, or an emergency blanket

2. Fire: a candle or other firestarter and matches in a waterproof container

3. First aid supplies

4. Hydration: extra water and a means to purify more on longer trips

5. Illumination: a flashlight or headlamp

6. Insulation: extra clothing that is both waterproof and warm, including a hat

7. Navigation: a topographic map and compass, in addition to a GPS device

8. Nutrition: enough extra food so you return with a little left over

9. Repair kit: particularly a knife for starting fires, first aid, and countless other uses

10. Sun protection: sunglasses and sunscreen, especially in the mountains

Just carrying these items, however, does not make you prepared. Unless you know things like how to apply basic first aid, how to build an emergency fire, and how to read a topographic map or use a compass, then carrying these items does you no good. These skills are all fairly simple to learn, and at least one member of your group should be familiar with each of them.

More important to your safety and enjoyment than any piece of equipment or clothing is exercising common sense. When you are far from civilization, a simple injury can be life-threatening. Don’t take unnecessary chances. Never, for example, jump onto slippery rocks or logs or crawl out onto dangerously steep slopes hoping to get a better view. Fortunately, the vast majority of wilderness injuries are easily avoidable.

Advice for the First-Time Backpacker

There is something enormously liberating about spending a night in the wilderness. Many of the Pacific Northwest’s most spectacular attractions are beyond the reach of a comfortable day hike, leaving them for the overnight hiker to enjoy. But there are a few things to keep in mind as you plan your first few backpacking trips.

Differences Between Backpacking and Day Hiking

Many people who regularly take day hikes assume that backpacking is just day hiking plus spending the night. Wrong! The two activities have some very important differences.

PHYSICAL DEMANDS People often assume that since they regularly go on day hikes of 10 miles or more, they can cover the same distance when carrying overnight gear. This is a fundamental error because backpacking is an activity in which gravity displays its most sinister qualities. Your hips, shoulders, feet, knees, and probably a few body parts you had not even thought about in years will feel every extra ounce.

HIKING COMPANIONS Perhaps even more important, backpacking calls for a different mental attitude. It is usually unwise, for example, to travel alone, at least on your first few trips. This advice applies even to people who regularly take solo day hikes. Most people assume that this recommendation is for safety reasons, but while there is some safety in numbers, the main reason not to go backpacking alone is mental. Human beings are social animals. Most people enjoy backpacking (or any activity) much more if they have along at least one compatible companion with whom they can share the day’s events and experiences. Having a hiking partner will also make your journey more comfortable because you can lighten your load by sharing the weight of community items such as a tent, cookstove, and water filter. If you don’t have the sales skills to talk reluctant friends or skeptical family members into coming along, consider joining a hiking club, where you will find plenty of people with similar outdoor interests. (See Appendix C, for the names and addresses of some local organizations.)

Having good company on the trail (in this case, the Deschutes River Trail) can make your backpacking trip even more enjoyable.

SKILLS NEEDED Another thing that distinguishes backpacking from day hiking is that backpackers need a different set of skills. They need to know how to hang their food to keep out bears and other critters. They need to know how to select an appropriate campsite, one where breezes will keep the bugs away, where there aren’t dangerous or unstable snags overhead, where the runoff from overnight rains won’t create a lake beneath their tent, and a host of other variables. They need to know the optimal way to put things into their packs (where heavy items belong versus lighter ones) to carry a heavier load in the most comfortable way possible. Although the list of skills is long, they are all interesting, relatively easy to learn, and well worth the time and effort to acquire. (Turn to the recommended reading section in Appendix B, for a list of books that will help.)

IMPACT ON NATURE One final, often-overlooked difference between day hiking and backpacking is that backpackers need to be much more careful to minimize their impact on the land. All hikers should do things like pick up litter, avoid fragile vegetation, avoid cutting switchbacks, and leave wildlife alone. For backpackers, however, there are additional considerations.

Because you’ll probably be doing a lot of wandering around near camp, it is crucial that you put your tent in a place that is either compacted from years of use or can easily take the impact without being damaged. A campsite on sand, on rock, or in a densely wooded area is best. Never camp on fragile meadow vegetation or immediately beside a lake or stream. If you see a campsite starting to develop in an inappropriate location, be proactive: place a few limbs or rocks over the area to discourage further use, scatter horse apples, and remove any fire-scarred rocks.

In a designated wilderness area, regulations generally require that you camp at least 100 feet from water. In places with long-established camps that are already heavily impacted, however, land managers usually prefer that you use the established site, even if it is technically too close to water, rather than trampling a new area.

CAMPFIRES Do not build campfires. Although fires were once a staple of camping and backpacking, today few areas can sustain the negative impact of fires. In many wilderness areas and national parks, fires are now officially prohibited, especially at higher elevations. For cooking, use a lightweight stove (they are more reliable, easier to use, and cleaner than fires). For warmth, try adding a layer of clothing or going for an evening stroll.

EQUIPMENT Probably the most obvious difference between day hiking and backpacking is the equipment involved. Like day hikers, all backpackers should carry the “10 Essentials” listed in the previous section. But when you are spending the night, there are numerous other items you will need to remain safe and reasonably comfortable. Important items that every backpacker should carry but that day hikers rarely need include:

• A sleeping bag or backpacking quilt (preferably filled with synthetic material, as down doesn’t work as well in our wet climate)

• A tent (with a rain fly, mosquito netting, and a waterproof bottom). And don’t forget to run a test by putting the thing up in the backyard first, so you aren’t trying to puzzle out how it works and discovering you are three stakes short of accomplishing the task as a rainstorm starts in the backcountry. (Don’t ask me how I know this—just take my word for it.)

• A water filter or other water-purification system

• A lightweight sleeping pad for comfort and insulation against the cold ground

• Fifty feet of nylon cord for hanging your food away from critters at night

• Personal hygiene items

• Insect repellent (especially in July and early August in the mountains)

• A lightweight backpacker’s stove with fuel, cooking pots, and utensils if you want hot meals

Gear

FOOTWEAR The appropriate hiking footwear provides stability and support for your feet and ankles while protecting them from the abuses of the environment. A pair of lightweight hiking boots or trail-running shoes is generally adequate for most hikes, though hikers with weak ankles may want to opt for heavier, midweight hiking boots. When selecting footwear, keep in mind that the most important feature is a good fit—your toes should not hit the front while going downhill, your heel should be locked in place inside the boot to prevent friction and blisters, and there should be minimal extra space around your foot (although you should be able to wiggle your toes freely). When lacing them, leave the laces over the top of your foot (instep) loose, but tie them tightly across the ankle to lock the heel down. Break in new boots before taking them on an extended hike to minimize the chance of blisters—simply wear them around as much as possible beforehand.

SOCKS After armpits, feet are the sweatiest part of the human body—and wet feet are much more prone to blisters. Good hiking socks wick moisture away from your skin and provide padding for your feet. Avoid cotton socks as these quickly saturate, stay wet inside your shoes, and take forever to dry. Wool provides warmth and padding and, while it does absorb roughly 30 percent of its weight in water, effectively keeps your feet dry. If regular wool makes your feet itch, try softer merino wool. Nylon, polyester, acrylic, and polypropylene (also called olefin) are all synthetic fibers that absorb very little water, dry quickly, and add durability.

Middle Rock Lake, on the Shellrock and Serene Lakes Loop (Trip 46), makes a good goal for an intermediate-level backpacking trip.

BLISTER KIT Blisters are usually caused by friction from foot movement (slippage) inside the shoe. Prevent them by buying properly fitting footwear, taking a minimum of one to two weeks to break them in, and wearing appropriate socks. If your heel is slipping and blistering, try tightening the laces across your ankle to keep the heel in place. If you notice a blister or hot spot developing, stop immediately and apply adhesive padding (such as moleskin) over the spot. Bring a lightweight pair of scissors to easily cut the moleskin.

FABRICS Avoid wearing cotton—it absorbs water quickly and takes a long time to dry, leaving a cold, wet layer next to your skin and increasing the risk of hypothermia. In hot, dry environments, however, cotton can be useful as the water it retains helps keep you cool as it evaporates. Polyester and nylon are two commonly used, and recommended, fibers in outdoor clothing. They dry almost instantly, wick moisture effectively, and are more lightweight than natural fibers. Fleece (made from polyester) provides good insulation and will keep you warm even when wet, as will wool and wool blends. Synthetic materials melt quickly, however, if placed in contact with a heat source (campstove, fire, sparks). A lightweight down vest or jacket adds considerable warmth with minimal bulk and weight, though it must be kept dry—wet down loses all of its insulating ability.

RAIN AND WIND GEAR Good raingear is crucial for hikes in the Pacific Northwest. There are three types available: waterproof and breathable, waterproof and nonbreathable, and water-resistant. Waterproof, breathable shells contain Gore-Tex or an equivalent material and effectively keep water out while allowing water vapor (i.e., sweat) to pass through. They keep you more comfortable during heavy exertions in the rain (though you will still get damp from the inside) and are generally bulky and more expensive. Waterproof, nonbreathable shells are typically made from coated nylon or a rubberlike material. They keep water out but hold all your sweat in, but they are cheap and often very lightweight. Water-resistant shells are usually lightweight nylon windbreakers coated with a water-repellent chemical. They will often keep you dry for a short time but will quickly soak through in a heavy rain. All three are good in the wind.

HATS AND GAITERS The three most important parts of the body to insulate are the torso, neck, and head. Your body will strive to keep these a constant temperature at all times. A thin balaclava or warm hat and neck gaiter are small items, weigh almost nothing, and are more effective at keeping you warm than an extra jacket. Add a lightweight pair of gloves in the spring and fall, and in alpine regions.

PACK For most people, an overnight pack with 3,000–4,000 cubic inches of capacity is generally necessary, though many ultralight hikers get away with less. The most important feature is a good fit. A properly fitting backpack allows you to carry the majority of weight on your hips and lower body, sparing the easily fatigued muscles of the shoulders and back. When trying on packs, loosen the shoulder straps, position the waist belt so that the top of your hips (the bony iliac crest) is in the middle of the belt, attach and cinch the waist belt, and then tighten the shoulder straps. The waist belt should fit snugly around your hips, with no gaps. The shoulder straps should rise slightly off your shoulders before dipping back down to attach to the pack about an inch below your shoulders—weight should not rest on top of your shoulders, and you should be able to shrug them freely. Most packs will have load-stabilizer straps that attach to the pack behind your ears and lift the shoulder straps upward, off your shoulders. A sternum strap links the two shoulder straps together across your chest and prevents them from slipping away from your body. Most packs are highly adjustable—a knowledgeable employee at an outdoor-equipment shop can be help you achieve the proper fit. Load your pack to keep its center of gravity as close to your mid- and lower back as possible. The heaviest items should go against your back, and you should pack items from heaviest to lightest outward and upward. Do not place heavy items at or below the level of the hip belt—doing so precludes the ability to carry that weight on the lower body and is one of the main reasons packs feature sleeping bag compartments in that location.

EXTRAS A length of nylon cord is useful for hanging food, stringing clotheslines, and guying out tents. A simple repair kit should include a needle, thread, and duct tape. A plastic trowel is nice for digging catholes. Insect repellent will keep the bugs away; Deet-free versions are increasingly common. A pair of sandals or running shoes for around camp is a great relief from hiking boots. A pen and waterproof notebook allow you to record outdoor epiphanies on the spot. Extra zip-top or garbage bags always come in handy. Compression stuff sacks will reduce the bulk of your sleeping bag and clothes.

Make sure your camera is ready for outdoor abuse, and keep it safe from dirt and moisture. A good protective camera bag costs much less than a new camera. A polarizing filter is good for taking outdoor pictures with lots of sky and water. Also consider a small tripod for low-light photography, binoculars, a Frisbee, and playing cards.

Reintroducing Yourself to Backpacking

Maybe it’s been a while since you slept beneath the stars. If your last backpack was bright orange with an industrial-grade external frame and your sleeping bag weighed 25 pounds, you are in for a pleasant surprise. The synthetic clothing and high-tech gear described in previous sections deliver much higher performance at a much lower weight than in the old days, and more so every year. If you’re not sure how much backpacking you’ll want to do, try renting a pack for your first trip or two; most outdoors stores have rental models they can fit for you.

One more thing to note if you haven’t backpacked recently: places that you previously visited on the spur of the moment may now require permits—to park at the trailhead, to spend the night, or even to hike the trail at all. Each hike profiled here lists any permits required; how much they cost, if anything; and where and how to get them.

The first step for anyone contemplating a backpacking trip is to get into some kind of reasonable shape. Blisters while you hike and painfully sore muscles when you return are not badges of honor; they just hurt. Therefore, some simple, regular aerobic exercise and strengthening key muscle groups (such as the calves, thighs, and shoulders) are crucial to having a good time.

Step two is to gather together all the gear you’ll need. You remember—it’s that pile of musty stuff in the basement that you haven’t looked at in years but haven’t had the heart to give away since you always told yourself you’d use it again. Pull it all out, clean it up, and check for and repair any damage, such as seams that have torn, places where mice have chewed through the shoulder straps, and tent seams that are no longer waterproof. Make sure things still fit properly (no offense, but that hip belt might need to be let out some). Finally, using the suggested gear list in the previous chapter, decide if you have everything you need and if newer versions of any of your old equipment might be significantly improved.

Introducing Your Kids to Backpacking

Even though it requires considerably more work and planning, few things in life are more gratifying or enjoyable than taking a kid backpacking. One big reason for this is that children have the unique capacity to renew your appreciation of the outdoors. No matter how commonplace and mundane things may be to you, everything is new and interesting to a child. The list of wonders includes all kinds of “little” things—mushrooms, tadpoles, fern fronds, discarded feathers—that many adults no longer appreciate or even notice. In fact, it is downright humbling to see how much a child notices, and the feeling is only slightly reduced by the realization that children possess a natural height advantage when it comes to seeing things that are close to the ground.

Although backpacking with a child may be fun for the adult, it is even better for the kid. A growing body of evidence suggests that regular contact with the outdoors is a natural antidote for attention deficit disorder, depression, and obesity and is crucial for a child’s overall mental and physical development. What better way to fill that need than to take them to a place where electronic screens simply aren’t an option, and where they can explore a world filled with newts and flowers, pine cones and toads, and countless other real-world wonders?

To ensure that the backpacking experience is a great one (for both young and old), here are a few tips and guidelines to keep in mind:

• When backpacking with young children, leave the teensy, ultralight, supposedly-for-two-people-but-only-if-they-are-on-their-honeymoon tent at home, and pack a nice roomy shelter.

• Don’t forget that children, much more than adults, need a few comforts of home. Bringing along that favorite blankie, stuffed animal, or bedtime storybook may be essential to everyone getting a good night’s sleep.

• Remember that young bodies are less tolerant of weather extremes than older ones. Precautions such as sun protection, drinking plenty of water, and bundling up for the cold, for example, are all much more important for children than adults.

• Recognize that your kids will get dirty—probably downright filthy, in fact. Live with it. Don’t bother to scrub them clean every time you see them. Getting dirty usually means they are having fun.

• If your kids are too young to recognize natural dangers (poison oak, steep drop-offs, anthills, and the like) then you will need to physically block these off or designate an adult to keep watch.

• A little entertainment makes a big difference. In the evening, kids love the idea of having a headlamp, so bring along one for every member of the party. Bring simple games. Playing cards, pick-up sticks, and small board games all work well. Finally, don’t forget to brush up on your storytelling. It is still the best way to spend an evening with kids in the outdoors.

• Don’t forget to bring snacks—lots of ’em.

• Get the kids involved in the planning. Delegate to older kids tasks like planning the menu and checking the weather, and consider providing each kid with a printed map or a notebook for recording their impressions along the trip.

• Be thoroughly familiar with child first aid, and recheck your first aid kit to ensure that it contains children’s aspirin, lots of bandages (often great for psychological comfort even when the child isn’t really hurt), and tweezers for removing splinters.

• Consider bringing along the child’s best friend, or even that friend’s whole family. It may not fit with your idea of solitude in the wilderness, but kids usually love having a playmate while exploring the outdoors.

• How much leeway and independence you give your children depends on their ages and ability to follow instructions. But even the most responsible youngsters may at times stray too far from camp when searching for huckleberries, chasing a squirrel, or engaging in some other equally distracting activity. To help combat this problem, all children should carry a whistle, preferably on a necklace, that they have been instructed to blow if (and only if) they become lost.

Tadpole watching at Rush Creek, Indian Heaven Wilderness (Trip 23)

photo by Douglas Lorain

Your choice of backpacking location is especially crucial when traveling with young hikers. Unlike adults, children are rarely impressed by great views and invariably complain about steep climbs. (To be fair, adults often complain about steep climbs as well.) This book includes dozens of backpacking trips that are especially well suited to children. Identified both in the summary chart and by icons on the first page of each individual hike, these trips are relatively short, involve less elevation gain, and include plenty of the things that youngsters love—splashing creeks, wildlife, berries, lakes to explore, and the like.

Elk Meadows (Trip 37) boasts a picture-postcard view of Mount Hood.

photo by Paul Gerald

An excellent time to schedule a backpacking trip with kids, especially into the Cascade Mountains, is late August. This is huckleberry season, when children (and adults) can stuff themselves with handfuls of the delicious berries. In fact, one measure of the success of a hike at this time of year is how purple one’s fingers and tongue are by day’s end. In addition, the mosquitoes are usually gone by this time, and the mountain lakes remain warm enough for a reasonably comfortable swim. Finally, your trip will take place just before kids go back to school, so they will have impressive stories to tell when the teacher asks the inevitable, “So what did you do this summer?”

For further information on backpacking with children, see the recommended reading in Appendix B.

How to Use This Guide

The trips in this book are broken down by geographic region, starting from the southeastern Olympic Mountains in the north and working down to the Mount Jefferson and Mount Washington area in the south.

Each individual trip begins with a quick overview of the hike’s vital statistics, including scenery, solitude, and difficulty ratings, as well as distance, elevation gain, managing agency, best time to visit, and more. This allows you to rapidly narrow your options based on your preferences, your abilities, and the time of year.

Just below the trip title are numerical RATINGS (1–10) of the three qualities that traditionally attract or deter hikers the most: scenery, difficulty, and the degree of solitude you can expect.

The SCENERY rating is my opinion of the trip’s overall scenic quality on a 1 (just OK) to 10 (absolutely gorgeous) scale. Of course, this rating is completely subjective: I happen to swoon over alpine meadows sprinkled with wildflowers, while you might prefer a riverside trail through deep woods. There are no bad choices; every hike in the book has beautiful scenery, it’s just that some of them are so spectacular they’ll make your wide-angle lens think it died and went to heaven.

The DIFFICULTY rating is also subjective and runs from 1 (barely leave the La-Z-Boy) to 10 (the Ironman triathlon). Keep in mind that this book is designed not necessarily for lifelong backpackers but for those of us who don’t manage to get out there as often as we’d like. We might be fitter than average, but we’re not in the habit of carrying all our food and shelter (and maybe our children’s food and shelter) up steep and rocky mountain trails. The difficulty ratings reflect this; the few hikes rated a 1 are either nearly flat or very short, or both. Hikes rated 9 or 10 are extremely challenging (but so rewarding!). I’d prefer to have someone leave the trail thinking, “That was easier than I expected,” rather than, “Good grief, if that was a 5, I’m not even going to think about trying a 9!”

Because SOLITUDE is one of the things backpackers are seeking, it helps to know roughly how much company you can expect. This rating is also on a 1 (bring stilts to see over the crowds) to 10 (just you and the marmots) scale. Of course, even on a hike rated 10, it is possible that you could unexpectedly run into a pack of unruly Cub Scouts, but generally this rating is pretty accurate. Note that there are trade-offs: extreme solitude usually means the trailhead is hard to reach. To boost your chances of camping solo in more popular, accessible areas, try to go midweek or in the shoulder seasons.

The next two lines list total ROUND-TRIP DISTANCE and ELEVATION GAIN for that trip. For many hikers, the difficulty of a trip is determined more by how far up they go than by the mileage they cover, so pay especially close attention to the second number, which includes the total of all ups and downs, not merely the net change in elevation.

Every trip includes a map that is as up-to-date and as accurate as possible. But common sense dictates that you’ll also want to carry a topographic map. The OPTIONAL MAP entry identifies our recommended map(s) for the described trip.

Next you will find two seasonal entries. USUALLY OPEN tells you when a trip is typically snow-free enough for hiking (although this can vary considerably from year to year). BEST TIME lists the particular time of year when the trip is at its best, such as when the flowers peak, the huckleberries are ripe, or the mosquitoes have died down.

AGENCY is the local land agency responsible for the area described in the hike; these are the people to call if you need a map or want to double-check road and trail conditions before setting out.

PERMIT tells you if a permit is currently required to enter or camp in the area and how to obtain one. It notes the few instances when permits are not free or advance reservations are required, along with the necessary details. When a Northwest Forest Pass is required to park at the trailhead, this is also indicated. (If you’re planning to do a lot of hiking in the area, it’s worth buying the $30 annual Northwest Forest Pass to keep in your vehicle; if you’re going only once or twice, you can usually buy a day pass at the parking area for $5.)

ICONS AND TRAIL USES:

This hike is good for children.

Pets are allowed, and the trail is both safe and suitable for dogs.

HIGHLIGHTS: This quick preview of each hike’s main characteristics—epic views, ferns and fir trees, a pretty lake—should give you a sense of whether this particular trail is the kind of thing you’re looking for.

GETTING THERE provides driving directions to the trailhead from Portland, including GPS coordinates for the trailhead. As you plan your trip, keep in mind that it can take 3 hours to drive 70 miles if half of those miles are on rough or winding gravel roads. Don’t trust the maps app on your smartphone; allow extra time to reach out-of-the-way hikes.

In HIKING IT, we describe your hiking route in detail, beginning at the trailhead and on through each trail junction you’ll encounter.

Get a healthy dose of moss-covered rocks along the Duckabush River Trail (Trip 1).