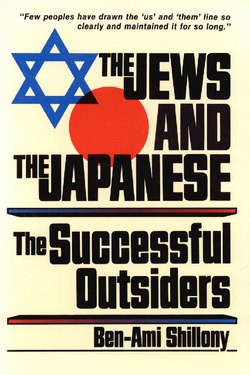

Читать книгу Jews & the Japanese - Ben-Ami Shillony - Страница 16

Оглавление7

Master or Genius?

THE JEWS and the Japanese joined the modern West with an ambition to excel, but because their traditions and historical experiences differed, the ways in which they proved themselves also differed. The basic Jewish position vis-a-vis the world had been one of nonconformism. As a small monotheistic people in an ocean of pagan culture and later as a small non-Christian or non-Moslem community in an ocean of Christendom or Islam, Jews had become accustomed to challenging accepted customs and values. Their survival as a nation and a religious group depended upon courage to adhere to beliefs and modes of behavior that differed from the majority of those among whom they lived. The Japanese, on the other hand, did not develop such a tradition. Confucian morals and bushido (the ethical code of the samurai) stressed the importance of conformism and obedience to accepted standards. Success and advancement were achieved not by dissenting but by outperforming. When the Japanese adopted Chinese civilization in the first millennium C.E., they showed their ingenuity not by challenging concepts and standards of that civilization, but by striving to implement them in what they believed was a more efficacious way.

There was considerable intellectual freedom in premodern Japan. Different schools existed for almost every cultural activity, from flower arranging to martial arts and philosophy. Although each school prescribed its own way of doing things, there was little animosity between them. Choosing a particular school, like choosing a game, was a matter of taste rather than of conviction, but once a school was chosen, one had to abide by the rules of the game; like in sport, success depended on performing well according to set rules. Accomplishment was a matter of rigorous training combined with personal style.

When the Japanese decided to adopt the Western culture, they went about it in the same sportsmanlike manner. Previous games were not discarded, but anyone wishing to play the Western game had to abide by its rules. Copying details was the only way to learn the new rules. All of Japan's accomplishments in modern times have been attained by outperforming the West according to the rules established by the West. Thus, when Japan defeated czarist Russia in 1905, it was not the victory of an Oriental power over an Occidental one, but rather the victory of a more modern Japan over a less modern Russia. Japanese industry, military, commerce, education, law, bureaucracy, and parliament were all established on Western principles. Traditional elements were incorporated, but the basic rules were Western. Consequently, when the Japanese acquired their first colonies, Taiwan and Korea, they ruled them as ruthlessly as the Western powers ruled their own colonies at that time.

The enthusiasm for practical solutions and disinclination to engage in theoretical polemics was evident in social and political thought. The Meiji-period (1868-1912) leaders who built the new Japan set pragmatic goals: a rich country and a strong military. They had no intention of creating the "new man" or of offering new formulas for the solution of the world's problems. They did not give their policies theoretical names and had little interest in providing a model for other countries to follow. Japan built a successful modern state and a dynamic and orderly modern society without formulating a new theory of how a state or a society should be maintained or managed. Japan is probably the only country in the world that has transformed itself quickly without recourse to any grand ideology, and the Japanese leaders are probably unique in not having any "-isms" or doctrines associated with their names.

The Jews excelled in Western culture through a different course. Their historical position as nonconformists and challengers of accepted truths, and their long tradition of theoretical argumentation produced an emphasis on creativity rather than on accomplishment. Whereas the Japanese tried to outperform their Western competitors, the Jews sought to revise, redraw, and replace the basic tenets of the West. The epitome of Japanese achievement was the master, at the pinnacle of Jewish success was the genius.

The nineteenth and twentieth centuries have seen Jewish "geniuses" appear in numbers out of all proportion to the Jewish population. While Jews in modern times have constituted only about two-tenths of one percent of the world population, about 20 percent of the recipients of the Nobel Prize in physiology, medicine, and physics have been Jews. It is difficult to imagine the world today without the contributions of Karl Marx, Leon Trotsky, Sigmund Freud, Alfred Adler, Albert Einstein, Franz Kafka, Marcel Proust, Emile Durkheim, Henri Bergson, Claude Levi-Strauss, and many other Jewish scholars, writers, philosophers, and scientists. Most of these eminent persons were iconoclastic geniuses. They had detached themselves from Orthodox Judaism and some even converted to Christianity, but they all shared the Jewish trait of zeal in challenging accepted truths and searching out new ways of understanding the world. Carrying on the tradition of nonconformism and argumentation, they came to shatter accepted doctrines and to offer new theories and concepts.

Karl Marx was the grandson of a rabbi and a descendant of a line of talmudic scholars; his uncle was the chief rabbi in his native German town of Trier. Marx was baptized at the age of six and later heaped scorn on the Jews, accusing them of being capitalist manipulators, but his audacity in challenging philosophical assumptions and in offering a new way of achieving human salvation was rooted in the Jewish tradition of dissent and in the Jewish belief in a future redemption. Sigmund Freud was born in Vienna to a Jewish family that had emigrated from eastern Poland. Unlike Marx, Freud never abandoned Judaism, even though he was not a practicing Jew. Albert Einstein, however, was a proud Jew and an active Zionist; in 1952 he was offered the post of the president of the State of Israel, which he declined. Japan had no equivalents to Marx, Freud, or Einstein, because its society and value system were not structured to encourage opponents of conventional wisdom.

Many Jews who entered European society became wealthy and, although many more of them remained poor, it was the rich who captured the attention of the gentiles. The wealthy Jew is not a modern phenomenon. As moneylenders and merchants, Jews had already gained the reputation of being rich in the Middle Ages. But as long as they lived apart their wealth was less conspicuous than it was later, when they tried to become integrated into general society. The skill exhibited by Jews in commerce and in money-handling has made the terms "Jew" and "mammon" synonymous to many non-Jews.

Japanese modernization has also been evident in material terms—in the nation's factories, railways, large cities, and growing standard of living. The Japanese businessman has acquired the image of a ruthless, profit-seeking samurai, and the Japanese government has repeatedly been accused of helping its businessmen exploit foreign countries. Epithets recently popular, such as "Japan Inc." and "economic animal," attest to this image.

Indeed, both Jews and Japanese have used material gain to compensate themselves for various shortcomings and to prove themselves to the outside world. The Rothschild family attracted much attention in the last two centuries. An agent for the court in Frankfurt in the eighteenth century, the family by the beginning of the nineteenth century had opened financial branches in London, Paris, Naples, and Vienna. By the middle of the nineteenth century the Rothschilds were managing banks, floating government bonds, and building railways all over Europe, and had amassed a fortune sufficient to make them one of the richest families in the world. Money provided the Rothschilds with entry into a level of society hitherto denied ordinary Jews. In 1822 Salomon Rothschild was ennobled in Austria, and in 1861 his son Anselm was appointed to the Austrian House of Lords. The same year Mayer Rothschild was elected to the North German Reichstag and shortly afterwards was appointed to the Prussian House of Lords. In 1858 Lionel Nathan Rothschild became the first Jewish member of Parliament in Britain, and in 1885 his son Nathaniel became the first Jew of the British peerage, while in France the Rothschilds were made barons. The fact that the Rothschilds were Jews made them more conspicuous and less secure, and they clung together to insure their position and influence.

The closest Japanese equivalent to the Rothschilds was the Mitsui family. Starting with a textile shop in seventeenth-century Edo, the Mitsuis branched into moneylending in the major cities and by the end of the century became the financial agent of the shogun. Like Nathan Mayer Rothschild, who became rich by backing the winning British army against Napoleon, so the House of Mitsui became rich by backing the winning Imperial Army against the shogun. Following the Meiji Restoration, the Mitsui family established banks, set up a trading company, ventured into mining, invested in shipping, and acquired industries. By the beginning of the twentieth century Mitsui was the largest business combine in Japan. Unlike the Rothschilds, however, the Mitsui family did not continue to run its own enterprises itself. After the Meiji Restoration actual management was in the hands of competent employees who were not family members. No member of the Mitsui family made a personal impact on modern Japan. It was rather the Mitsui combine, the Mitsui companies, and the Mitsui managers who wielded the power and gained the fame.

Many people in the West regarded the Rothschild and Mitsui families as representative of the Jews and the Japanese, personifying their alleged attachment to material values and desire to control. Indeed, members of the Rothschild family often served as leaders of various influential Jewish organizations, and managers of the Mitsui conglomerate wielded influence over the Japanese government. The Rothschilds and the Mitsuis represented, however, only one aspect of Jewish and Japanese societies. Other aspects, less conspicuous but no less important, complemented and balanced this desire for material success. In traditional Jewish society the most prestigious members were not the rich but the learned. The brightest children were encouraged to become talmudic scholars rather than prosperous merchants.

Charity occupied a central place in Jewish life and the Talmud equates its importance with all the other commandments combined. In the Middle Ages charity was the most important activity of Jewish communal life and one that enabled the Jews to survive great hardships. The institution of charity was carried over into the modern era and is still widely practiced by Jews all over the world. The so-called "greedy Jew" has often been eager to give away a substantial part of his money not only to help his less fortunate brethren but also to help less fortunate gentiles. Jews have been among the leading philanthropists of modern times. The Rothschilds built schools and hospitals in many countries, and the Guggenheim family donated large amounts of money for the promotion of arts and sciences in the United States. Julius Rosenwald, an American Jewish businessman, established thousands of rural schools for black children and built model housing for blacks in Chicago at the beginning of this century.