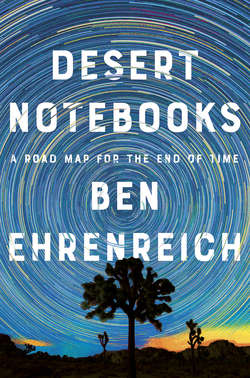

Читать книгу Desert Notebooks - Ben Ehrenreich - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1.

Of an evening the owls come out.

—ARTHUR BERNARD COOK

In the third week of November, one year and six days after the election of the Rhino, I went for a walk with two friends. It was late afternoon. The light was soft, the shadows long. We parked the car on a dirt road about a mile from my house, shimmied under the wire that marked the boundary of Joshua Tree National Park, and walked up through a wide sand wash that I had hiked many times before. As it ascended, the wash would become a canyon: walls of lumpy, reddish stone would rise to the east and west, narrowing as the canyon climbed south into the park. We were following in reverse the path the rain had carved over the centuries as it trickled and sometimes raged down from the rocky hills into the flat, sandy basin below.

Not far from there, in late July, a young couple had gone missing. They were kids from the suburbs, but even if you know the desert it isn’t hard to lose your bearings. Canyons fork and twist. The landscape plays tricks on the eyes. The light shifts and familiar terrain becomes suddenly alien. The summer had been a mild one, but most days it was still above 105. Search parties and helicopters scoured the area for weeks. The missing couple came up in every conversation I had in town: Maybe coyotes had already scattered their bones, or they had been abducted by some sinister stranger. Perhaps they had simply wanted to disappear.

In mid-October, searchers found them a couple of miles from my house, and maybe a mile from the wash in which my friends and I were hiking. The young woman’s father led the group that found them. The corpses, the newspapers did not neglect to report, were intertwined, embracing even in death. A few days later the authorities revealed that they had found a pistol at the scene: the young man had shot the young woman before turning the gun on himself. Police didn’t believe there was any malice in it. The pair appeared to have gotten lost and, having run out of food and water, chose to avoid a slower death. The fact that they had brought a handgun on a day hike was apparently so normal that few of the news reports considered it worth highlighting.

But the summer had passed, the monsoons had poured down in September, and though no rain had fallen since, the senna and brittlebush were still in bloom, smearing the sides of the wash a brilliant yellow. I don’t remember what we were talking about—maybe Steve Bannon or the lost hikers or Roy Moore banned from the mall, or the elusive scent of the desert willows that thicketed the floor of the wash—when K., walking ahead of A. and me, stopped. She pronounced a single word: “Owls.”

They took to the air in a sudden rustling burst, and then went silent. I barely glimpsed the first one: a flash of wide, white wings as it glided by above us, too big a thing to be so quiet. It soared off in a broad arc and disappeared behind a hill to the west. The second one, though, passed low enough that for an instant I could see its flat, tawny face, the mottled white and brown plumage of its belly, those bright, alien eyes. It circled once and flew out of sight to the east.

Eventually we breathed. With all their circling and swooping, K. thought maybe there had been three of them, but I was fairly sure there were just two. We kept walking, the wash narrowing as we went until we had to scramble over boulders to proceed. We turned a bend. The owls were there, perched on a rock. They saw us first and flew off up the canyon. Again they separated, one arcing right, the other left. We thought that was it and picked up the conversation again. I know at some point we talked about Lebanon and Saudi Arabia, Saad Hariri’s strange flight to Riyadh, Jared Kushner’s visit the week before. All of that had filled me with a panic that lasted for days, the contours of the next global conflict revealing themselves, requiring only the smallest flame. Who would play the role of the archduke this time? Who would kill him? K. stopped again. The owls had roosted in the rocks ahead of us, as if they were waiting for us there. They flew off and again we watched in silence.

So it went. We scrambled on, following the canyon as it twisted left or right, expecting to see the owls at every bend. Every hundred yards or so we caught up with them and everything we had been saying felt suddenly impertinent, and we fell silent until they flew off and then walked on until we caught up with them again. We talked more quietly now, still surveying the crises of the day, pausing to admire a paper-bag bush in unlikely late-autumn bloom or a particularly bold and healthy cholla. And then the owls shut us up again. We saw them five times in all, maybe six, before they soared off into some more distant canyon and disappeared for good. I knew that we had been annoying them, that they were only trying to avoid us, and it’s foolish, I know, but this is what humans do—we turn the world into a story and put ourselves at the center of the plot—and I found it hard not to imagine, or to want to believe, that they had been leading us onward all along, that they were trying to tell us something, or to show us a path, one that led deeper into the wilderness, away from the highway, away from the car.

Before we said goodbye that night, in the parking lot of the town’s one Indian restaurant, the conversation turned to writing. A. and K. are both writers. It was getting harder, we agreed, to muster faith in any of it, to care at all about lit-world battles that had once seemed so important. Or even, in the face of real, planetary disaster—glaciers melting, oceans rising, droughts and fires and famines and floods—to care about something we had once confidently called literature. No matter how pointless things may have felt at any given moment, A. said, you could always tell yourself that you were taking part in a conversation, an exchange that stretched back into the immeasurable past and on into a future that you couldn’t yet imagine. That was the conceit. Not progress but continuity, at least. You could tell yourself that it was the conversation that mattered, this stream of voices flowing through the centuries, this ancient, almost sacred thing that is bigger and deeper than any of us alone. But what if it’s going to end soon? What if someone in a generation, perhaps two, will write the very last word? What if the future does not include enough human beings to keep the conversation going? What if it drifts off like a party at the end of the night, with only a few drunks left mumbling in the corners? What if the humans who remain are too busy surviving to tend to the books and the servers? What if literacy has a horizon, and it’s near? Isn’t it all just noise then?

I should add that we were laughing, or smiling, at least. We were still high from the walk and it felt good to say these things aloud. The astounding vanity of it, I added, had never felt clearer, this hope that someone in a hundred years would hear you, that you might be able to give that person something, just like all the times you had been lifted and redeemed by the whispers of the dead rustling through the pages of books. How painful and absurd, this fantasy that your own labors might in turn be redeemed by strangers centuries and perhaps continents away who would need to hear what you had to whisper, this delusion that you were doing anything other than babbling because you like the sounds it makes, like a child blowing bubbles into milk. But without those strangers waiting for you, what is the point? Even if The New York Times loves you and everyone reads your books today and tomorrow and even next summer, what is any of it worth? Gossip squeaked between lemmings racing for the cliffs. Why bother to write when there will be no one left to read?

Really, I mean it when I say that we were smiling. We were talking about the end of time and the increasingly probable destruction of everything we knew and loved. We didn’t relish any of it, but in the context of the walk we had just taken, time took a different shape. The desert enforces its own perspective. It shrinks you and puts eternity in the foreground. If you’re open to it, and don’t mind a diminished role in this drama, it insists, quietly, on the surging beauty of all things and non-things living and dead and not-formally-alive.

I felt an unfamiliar gladness, soft and pressing, bubbling up. I’ve thought about it many times in the months that have passed since then: the strange, buzzing joy I felt standing in that parking lot saying goodbye and then driving home alone. Even at the time it felt crazy, like I really was high, though I was entirely sober. It was as if I knew—though I couldn’t have known—that I was stepping onto the path that these pages record, as if the joy of discovery preceded the exploration and I were grateful for a journey that I had not yet undertaken, that I didn’t even know I was on. I wouldn’t start writing until at least a week later, and when I did I had no idea it would become this book. I didn’t intend to write a book at all, much less to wage a battle against time, or at least against a certain conception of it, the one that still rules most of our lives and determines how we live them, how we conceive of what has passed before us and of the futures it might still be possible to build.

But that is what I did. That is where those owls would lead me. To fight against that notion of time, I would have to understand how it came to be shaped the way it is, and why we experience it as we do. I would have to ask what histories had to be erased and what new narratives invented for time to rule our lives this way. To figure out, if I could, how those omissions and accretions led us to precisely this perilous moment, in which everything, time included, appears to be on the verge of collapse.

When I did start writing, all I wanted was to remember the owls. I wanted to pin them down like any other memory, so that they wouldn’t fade too quickly. One day, if it occurred to me, I wanted to be able to read back and remember what it had felt like: the uncanny beauty of their flight, those late-autumn flowers, the violet light of dusk. But they didn’t let me. They wouldn’t stop flying. They disappeared behind the rocks and kept reappearing again and again. Weeks after I had left them, they led me to the Maya realm of the dead—you’ll see it soon enough—and from there to Hegel and Athena, and to the people who lived where I lived before I arrived there. I won’t tell you the rest but I kept following them because I was trying to understand not just time but writing too, and I realized that time and writing are inseparable. Writing extends us in time. It tries to. So that things won’t fade too quickly. And by writing I mean something more basic than what gets called literature: the act of inscribing, typing, scribbling, carving, or painting pictographs or glyphs or letters just like these, lines and arcs and loops that stand in for sounds and combine to form words capable of preserving thoughts, ideas, memories, impressions, histories, myths, all the immaterial substance of a culture, its battles over its own past and its present, and its battles over time, and over what it will fight to become.

In any case, I couldn’t have known, but there it is: somehow I knew, and I felt happy. Some part of me understood, and didn’t know how to tell the rest of me. Sometimes time moves like that, not straight but sideways, backward even, and, like the owls, in silence, in broad and looping arcs.