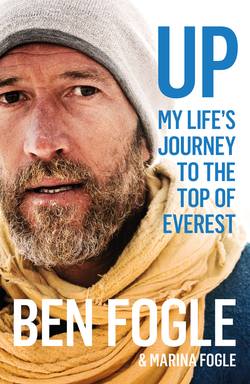

Читать книгу Up: My Life’s Journey to the Top of Everest - Ben Fogle, Ben Fogle - Страница 8

Introduction

ОглавлениеIt was a hot summer’s afternoon in 2016 and I was in a crowded tent at Goodwood House in Sussex. My wife Marina and I had been invited by Cartier to join them for lunch at the Festival of Speed. I made my way to our table and peered at the name card next to me.

Victoria Gardner.

I’d never heard of her, which was just as well, as she wasn’t there.

Thirty minutes passed and, after I’d finished my starter, a young girl appeared, apologised profusely for her lateness and sat in the chair next to me.

I recognised her instantly: Victoria Pendleton, the heroine of British cycling. Two-time Olympic gold medallist and umpteen-time world champion. I was dizzy with excitement. I had followed her career closely and admired her ability to excel at sport while not becoming a slave to it. I had always liked the way she spoke her mind and appeared to ruffle feathers by breaking convention. I admired her individuality in a sport with a reputation for unquestioning conformity.

I had long thought that Victoria would make a great adventuring companion if ever I met her. For several hours, we chatted. I told her that if ever she wanted to embark on an expedition or an adventure, I would love to explore some ideas. Without hesitation, she accepted, and in the inauspicious and unlikely surroundings of that marquee, we hatched a plan that would take us to one of the wildest, most dangerous places on earth, on a journey that would change our lives forever.

For several years, I had been travelling the world to spend time with people who had abandoned the conformity of society and followed their dreams into the wilderness. Each one had inspired me to do more with my own life, but each time I found myself returning home and plugging back into our ‘vanilla’ society. Safe. Risk averse. Conforming. Restricting. Angry.

I have always wanted more. I have always wanted to shake the manacles of expectation. Over the years, I have dipped in and out of it, but I have always returned to the safety of home and complacency.

I had been looking for something to shake my foundations and reconnect me with the wilderness.

The modern world is a complex one. Aged 44, I sometimes worry I can’t keep up with it. Technology and communication have advanced at breakneck speed. Never have we been bombarded with so much information. Never has society been held up to such scrutiny.

What’s more, we have become increasingly polarised. World politics is the manifestation of our fractured society. You are either in or out. For or against. Yes or no. Up or down.

Negativity is a blight on society. It might just be the rose-tinted retrospective reflection of my childhood, but I’m sure when I was younger everything was more positive. Negativity was the realm of Eeyore, the donkey from Winnie-the-Pooh. Eeyore was in the minority with his pessimism and gloom.

Today, there seems to be a bubbling undertone of resentment and anger that is contagious. It seems to manifest itself in this fast-paced, downward-looking burden. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

You can live your life Up.

I have always tried to look Up. That doesn’t mean I haven’t looked back, far from it, we can all learn a great deal from our past. From the highs and lows, the good decisions and the bad. The successes and the mistakes.

You see, looking Up has become something bordering on the spiritual. I am not religious, but that doesn’t mean I don’t look up.

‘Do you believe in God?’ asked my son Ludo one morning.

‘I don’t know,’ came the answer that surprised me. I’d probably describe myself as an atheist. I’m open-minded. I’ve been into the various churches of God over the years. I don’t have a particular calling to a specific ‘god’ per se, but that is not to say I don’t believe in a higher calling.

It’s just that mine is a little wilder. The wilderness is my religion. Nature. The flora and fauna. It is my church. I feel the same connection to a higher being when in the wilderness as many do in a church. My god is not specific. It’s the trees and the mountains and the rivers and the waterfalls. The wilderness heals; it soothes and calms.

Don’t worry, I’m not going to get too philosophical here, but it is important to understand my calling, because the wilderness in all her cloaks has a powerful spirituality. Of course, there are plenty of cultures who have long revered the sun and the moon and the power they have over us, and there are many pagans who also have a deep connection to the land and the earth.

Mine is less structured. It’s difficult to define, but I find the wilderness has an almost magnetic pull over me and perhaps it is the reason for this story. The call of the wild has helped mould and shape me into the man I am today. My relationship with the wilderness has never been one of battle or war. It has never been Man versus nature, but Man with nature. I’ve tried to find the careful balance of harmony, of mutual respect, of collaboration.

We have such a complex relationship with nature. In some ways, we have tried to tame it and control it: look at our cities and townscapes. We have beaten nature into submission, sanitised it and suppressed it. It’s almost as if we are terrified of it. Scared of its power over us.

I have never been fearful of the wilderness. Respectfully wary, and often humbled by it, but I’ve always loved being close to mother nature. She has a way of simplifying life.

Nature has the power to strip us back to our basic instincts. It’s no wonder there are movements around the world for rehabilitation and therapy in the wilderness, to use the forests and the woods as a way of treating ill health.

Forest schools are increasing in popularity and many nations, from Japan to Norway, have become popular destinations for forest bathing, in which people lie on the forest floor and stare up at the canopy above.

There is already scientific evidence of the healing virtues of the flora and fauna around us. It has always been perfectly obvious to me that we have a closer affinity to water, trees and mountains than we do to skyscrapers, roads and cars.

It feels like we have the very basics of our existence upside down. Rather than living in the concrete, grey cityscape and ‘escaping’ to the countryside for holidays or breaks, we should live closer to nature and ‘visit’ the cityscapes.

Of course, cities hold the key to work and opportunity, but once again we seem to have our principles and priorities slightly skewed. Do we work to live, or live to work?

I have always been attracted to a hand-to-mouth existence. A small-scale subsistence lifestyle has always seemed more compelling than the intensity of the materialistic, commercialised culture in which most of us in the Western world have chosen to live. Connected to the grid, we are slaves to money. We must pay taxes, mortgages and fees. The governments rely on a working society to generate income and therefore tax.

For the last six years, I’ve been working on a TV series about people who have dropped out of society and started a new life disconnected from the state. They have cut themselves off from ‘the grid’, severed their connection to electricity, water, gas, phone and in some cases money.

For me, expeditions have been my own, short-term opportunity to live off the grid. Expeditions have given me a chance to test my resolve and pique my resourcefulness. When I’m back at home, a cultural lethargy envelops me. When something goes wrong with the electrics or the car or the drainage, I will, by default, call in someone else to help.

The fully functioning circular economy relies on everyone having a skill. We have become reliant on a collective taskforce in which we all have mono skills rather than the universal multitasking multi-skills of old.

My late grandfather built his own house on the shores of a Canadian lake. He dug the foundations, installed the pipework and the electrics. He cut the wood, roofed the house and fitted the windows.

I like to think of myself as a well-rounded individual, but I wouldn’t know where to begin when it comes to building a house. I can sail, scuba dive and speak fluent Spanish, but I don’t understand electrics and I can’t even hammer a nail properly. Which set of skills are more useful? The latter of course; the problem is that society no longer requires them and we have lost the connection to our basic knowledge.

The wilderness requires resourcefulness; it forces us to connect with an inner self that once relied on survival skills to exist. When pushed, it’s amazing how adaptable we can become. The problem is that so few of us ever get a chance to test ourselves. We tend to take the easy option and avoid hardship. For me, expeditions have always been a way of reconnecting with my inner wildman.

The first time I really challenged myself was when I was marooned for a year on a remote corner of a windswept, treeless island in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. I had volunteered to be a castaway for a year on the island of Taransay, as part of a unique social experiment by the BBC to celebrate the millennium.

A group of 36 men, women and children were given 12 months to become a fully functioning community. We were given all the materials we would need to build accommodation, install water piping, a wind turbine and fencing. We put up polytunnels to grow fruit and veg in the inclement Scottish weather and we reared pigs, sheep and cattle. We built a slaughterhouse, harvested crops and became a simple, thriving off-grid community.

I learned so many new skills during that year: farming, building, teaching. In many ways, it converted a group of underskilled urbanites into a well-rounded, multi-tasking community, in which we all shared our different skill sets and knowledge for the betterment of the whole.

We became a very happy little settlement. I think we reintroduced lost values into our little community. We cared collectively for one another. There was no place for materialism. Our community was based on subsistence. We worked with what we had and maximised our efficiency. After 12 months, we were a happier, healthier, more efficient group of people.

In some ways, I have been chasing that beautiful, simple life ever since.

Castaway for a year on an island, rowing the Atlantic, trekking across Antarctica … all of these experiences have had a profound effect on me.

But it was Everest that changed me for good.

This seven-week expedition into the death zone was a life-changing, life-enhancing adventure. I walked the fine line between life and death. I experienced feelings and emotions that I’d never had before.

I never planned to write a book. After all, thousands of great mountaineering books have been written before. What would make my story so unique? Well, I hope you will read this book, not as an ego-chasing journey to the top of the world, but as a life-affirming lesson.

Humbled and enlightened, I hope these words jump out with the intensity of my own experience. I hope the positivity and the happiness and the joy overshadow the obligatory danger, fear and suffering that comes with a high-altitude mountain adventure.

I hope this book will inspire you to climb your own Everest.