Читать книгу More Than Miracles - Ben Volman - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1: Finding Laine

To say that Elaine was born into a missionary home means little today. There was a time when those words would have brought to mind exotic settings, foreign languages and intriguing new cultures. But she had her fill of that on the family mission field, Toronto’s inner-city Jewish neighbourhoods.

She grew up near the bustling mayhem of Kensington Market, where Jews from around the world, especially after World War II, crowded into the teeming narrow streets to find a bargain or drive a deal. Colourful baskets of fresh produce were lined along the sidewalks where the air was punctuated by the noise of shouting merchants, car horns and live chickens still in their cages. Cobbled alleyways were vibrant with conversations over open barrels with pickles or herring. Families and couples were drawn by the aroma of European bakeries to get coffee and pastries and for Shabbat (the Sabbath) pick from at least five types of challah—sweet egg bread—sliced to order. Behind the large shop windows were piles of fish over ice, glass cases stacked with waxed rounds of cheese and heavy blocks of halvah in gold and silver foil.

It was an old-world marketplace in the heart of staid Toronto, a bland grey city where immigrants found a bank and a church on every corner and solid middle-class proprieties. As a teenager, Elaine might have been embarrassed by the shouting fruit peddlers and raucous conversation between tailors and seamstresses pouring out of sweatshops. Yet this is where she came to feel most familiar, surrounded by jarring accents on hectic street corners.

Even today, Kensington retains many of its original quaint narrow Victorian “gingerbread” houses. In summer, they boast vivid garden plots or small squares of grass. Similar houses had once lined the market streets before they acquired storefronts and then brazenly pushed their sales-goods to the sidewalk. A world away from the average Toronto church parish, it was a remarkable backdrop for life-size drama, and the market streets of Kensington were just steps away from the broad thoroughfares of Spadina Avenue and College Street.

By the 1930s, Spadina, running south of College, had become the arterial mainstay of Toronto’s Jewish community. The avenue’s wide sidewalks had room for everyone with an opinion and a voice to hold a crowd. There were missionary preachers, union organizers and street-wise politicians of every stripe. When there was outrage or a strike or the people opened their hearts to a new cause, there was a march up Spadina—as they did in 1933, 15,000 strong to protest the anti-Semitic laws in Nazi Germany.1

At its lower end, Spadina was growing into an industrial centre for the Canadian garment and fur trade—the shmatte business—with a lively cast of entrepreneurs. The avenue was lined with dusty storefronts, each one a standard bearer for immigrant expectations of making a living in hats or lace, buttons or business suits, retail or wholesale. Down the centre of the avenue rolled the familiar TTC red-and-cream streetcars (the original “Red Rockets”). When the front doors slid open, people squeezed their way through the stone-faced newcomers, gripping bags full of groceries or dry goods. There was always a baby crying while a mother comforted her in some unknown tongue. When you got off, you couldn’t help noticing the chrome-gilded sedans filled with families who showed off the brash self-satisfaction of having arrived.

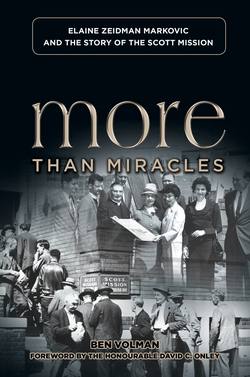

In November 1941, the Scott Mission was one of the newest ministries in the city but already one of the best known. Rev. Morris Zeidman and his wife, Annie, had been running the Scott Institute, a Presbyterian inner-city mission outreach to Jewish people, since 1927. During the Depression years, the Zeidmans came to citywide prominence when they expanded their ministry, going to extraordinary lengths to assist those who were impoverished by the economic tsunami sweeping the country. But by the early 1940s, those hard times were past. A thriving economy driven by the war in Europe meant that most people—and most churches—were no longer worried about the poor. After years of effective ministry, Zeidman became subject to petty complaints from his denomination about minor expenses. In frustration, he resigned his position with the Presbyterian church, closing the Scott Institute at the end of October 1941.

Giving up the security of a salary, missionary housing on which he paid no rent and the guarantees of his position with the church, Morris secured a double storefront on Bay Street. The day after the Scott Institute closed its doors, newspaper ads announced, “The Scott Carries On.” On November 1st the program of the institute would continue under a new banner: The Scott Mission. Even with a network of supporters and willing volunteers, they would face some very lean years.

The effect of all these changes on the Zeidman family happened well out of public view. The transition was hard on their four children, the oldest still only 13. They moved from the Mission quarters near Kensington at 307 Palmerston Ave. and College St. to a more conventional area in the east end of the city, north of the Danforth, between Woodbine and Main. The children considered themselves to be Jewish and had to cope with the culture shock of arriving in a typical Anglo-Canadian suburb. At the time, some 80 percent of Torontonians identified their origins as British. The open anti-Semitism among local children, even teachers, aggravated the family’s sense of isolation. (Very few Jewish teachers during the 1930s and ’40s were able to find work in Toronto schools.2) Nor did the neighbours bother hiding their prejudice. Some were particularly obnoxious, and one day the family came home to find the word “Jew” scrawled on the garage.3

Elaine, the younger daughter, had just turned seven. The family called her “Lainey”— spelled out as “Laine.” She was surrounded by two older siblings and a younger brother, all of them born three years apart between 1928 and 1937. Her practical-minded older sister, Margaret, had arrived while the family still lived in the original old Mission building at 165 Elizabeth St. Margaret had inherited her mother’s considerable musical skills in voice and piano. Alex, the older brother, was destined to carry himself with the bearing of a distinguished clergyman. He was a serious boy who enjoyed tinkering with mechanical projects, including a large crystal radio set, in the basement. The youngest, David, who would also play a leading role with the Mission, was a robust, happy child with great affection for his parents and siblings.

Laine was born in 1934 at the height of the Depression, a strikingly beautiful baby according to Margaret, but frequently ill. She was too young to remember her parents bringing her to Sick Children’s Hospital with peritonitis, which in those days was fatal. The revered family physician Dr. Markowitz was able to secure penicillin, which had just become available. Her fate was uncertain until she rallied, taking months to recover. Laine would always have a sensitive stomach and remained prone to infections, never so vigorous as her siblings.

One of Laine’s earliest memories was of her mother, thermometer in hand, deciding she was sick and hurrying them over to the family physician. Dr. Markowitz paid scant attention to the little girl, insisting that Annie immediately sit down and take a glass of wine.

At Christmas 1941, with the new Mission barely underway, Laine came down with scarlet fever. Public health officials treated the disease with extreme caution. Her parents couldn’t afford the $12 a week required to put her into a special hospital isolation ward and paid off the bill in instalments. (This was decades before publicly funded health care.) Morris, using his clerical privileges, came to visit, and the little girl didn’t recognize him under the full protective gown until she heard him say, “Laine, it’s me.”

By the time Laine returned home, her mother had the family schedule in order. Early each morning, Morris drove to the office, while she prepared the children for school. After they left, Annie took the streetcar and joined him downtown. It wasn’t an era of working mothers. Annie discreetly employed a homemaker so that she could put in a full day at the Mission, usually coming home exhausted.

For the Zeidman children, the Mission schedule was closely linked to family life. They helped out as best they could through the year, joining in regular family programs through fall, winter and spring and then residing at the summer camp with the other kids. When needed, they were extra hands and feet for innumerable daily tasks. As they grew older, each one in turn would find a place in the work.

It was a lively house, full of music and its share of laughter. Occasional evenings were spent singing around the piano—Morris loved to sing, and Annie had trained in voice as well as piano at the Royal Conservatory of Music. Everyone kept up a sharp sense of humour. When Alex was a theology student at Knox, Laine knit him a tie in the purple and grey colours of the college. She’d made it a bit long, so one morning he showed up at breakfast wearing his usual college tie and Laine’s knitted handiwork wrapped around his leg for decoration.

Despite their busy schedules, family members were expected to be home and gathered at the table for dinner, followed by a Bible reading with devotions. There were no more amusements once the Scriptures were opened. Morris and Annie were serious life-long Bible students. Only in time did Laine fully understand how much of the Word of God she’d absorbed from them, a lifetime’s treasury of wisdom and comfort that came to mind when it was most needed out of the lessons from her earliest years.

The hours after supper were equally occupied. Annie used the time to teach her daughters how to play the piano, and later that was time for practice. To help make ends meet, she sewed a lot of the children’s clothing. Morris, too, spent his evenings focused on studying and writing at the kitchen table. He relied on Annie to be his editor while he composed tracts and articles, plus his international correspondence. Always studying, Morris earned a PhD and was a Bible college teacher of Greek and Hebrew. Later, the children would recall vividly how Morris’s bedroom was filled with books, newspapers and clippings from newspaper subscriptions that kept him abreast of international news—in English and Yiddish—from across Europe and America.

Afterwards, Annie would read to the younger children. Those moments became some of Laine’s most precious memories. As a young child, she was encouraged to say prayers before bedtime. There was one she could easily recall and had taught to her own daughters:

Jesus, tender shepherd, hear me,

Bless thy little lamb tonight;

Through the darkness be thou near me,

Keep me safe ’til morning light.

During one of those prayer times, Annie wanted to know why her 11 year-old daughter was in an irritable mood. It eventually occurred to Laine that it was Miss Stacey’s fault. During the Sunday school lesson, Miss Stacey had asked the children in her class, “Has anyone here given their heart to Jesus?” Laine was troubled because she couldn’t say yes. So Annie began explaining how she could say yes, right then and there beside her bed. That was the moment when Laine prayed for Jesus to enter her heart.

As the family struggled to cope through numerous trials with the Mission over the next few years, Laine started to show a rebellious streak. During the first year of high school at Malvern Collegiate, her behaviour became a problem. She was seeing far too much of the detention room. Morris was embarrassed. He expected his children to the know the importance of education, but Laine didn’t act interested anymore. She was falling in with the wrong crowd.

Annie had taken each child aside when they were eight or nine years old and taught them, “Remember who you are.” They were responsible for being “a Zeidman.” There were standards to maintain—the conduct suitable for children of clergy. Young as they were, the message was clear: “We’re not like other families.” By high school, Laine seemed to have had enough of that. Some of her attitudes might have come from her teachers. Neither of her older siblings had excelled at that school, and Margaret described the teachers as openly anti-Semitic.

Morris was determined that his daughter was not going to give up on her education. Despite the cost, he placed her at Moulton College, a Baptist all-girls high school associated with McMaster University, where families in ministry received financial considerations.

Soon Laine would find a supportive circle of friends, although that didn’t seem so likely when she first arrived. The girls were fixing their place in the social order as each one answered the question, “Who’s your father?” Of course, she knew that many of the girls had heard of her father or The Scott Mission, but Laine wasn’t quite sure how to answer that question. Who was Rev. Morris Zeidman, and why was it so difficult being his daughter?