Читать книгу The Man in the White Suit - Ben Collins, Ben Collins - Страница 9

ОглавлениеChapter 3

Winning

I wanted to be inspired by something I could excel at, consumed with a passion to succeed. I caught the first glimpse of the path I wanted to choose on my eighteenth birthday.

My father’s exceptional gift was a trial in a single-seat racing car at the Silverstone Grand Prix circuit. I had only been driving for a few months – around the country lanes in my mother’s L-plated 4x4, with her riding shotgun. Mum hit me so often with her handbag that she broke the handle. Apparently I ‘left no margin for error’.

Dad had been raving about his experiences of racing; he’d just started competing himself. After a tooth-jarring trip across the snaking stretches of the Cotswolds with him working the wheel, we arrived at the circuit gates.

The moment we pulled off the road, the tarmac inside became more generous. Grandstands grew skywards in preparation for a big event and the unusual barrier walls were painted in blue and white blocks. I caught glimpses of the track from behind the grass banks. The bare breadth of bitumen with no road markings was unlike anything I had ever seen.

I climbed into one of my old man’s racing suits and tied on what looked like blue ballet shoes. A man gave a briefing to a group of us that involved plenty of crashing and potential death. We were using the high-speed Grand Prix circuit and had to show it due consideration.

The racing car was nothing much to look at. It lacked Formula 1 wings and hardly made a sound as the mechanics fired it up, but every component had an essential purpose. Business-like wheels carrying ‘slick’ tyres with no tread on them were attached to bony steel suspension arms bolted to a slender steel frame tub, at the front of which sat the nose, honed like the tip of a rocket. The bodywork was trim and crafted purely for speed.

Standing off to one side, I raised my right leg over a sidepod containing the cooling system, and into the cockpit. I rested one arm on the highest point of the car, just 30 inches from the ground, then pulled in the other leg. Standing on the moulded seat, I gripped the sides and slid my feet forwards.

The rev counter, speedo, oil and water temperature gauges were hidden behind the small black steering wheel, along with numerous mysterious buttons. The stainless steel gear stick to the right was the size of a generous thumb. It shifted with a delicate ‘thunk’ from one gear to the next.

My feet touched the pedals jammed closely together ahead of me. The brake was solid as a brick, the throttle stiff until you applied pressure, when it responded precisely to tiny movements. The steering felt heavy with no power assistance, only the strength I applied to it transferring energy to the front wheels which I could see turning ahead of me.

I tightened the belts and they jammed me into the seat, connecting me to the car. The hard seat grated at the bones in my shoulders. Everything was so alien, yet I knew it then. I was home.

The instructor deftly turned a red lever a quarter turn clockwise, flicked a pair of switches and an orange light glowed; the car was alive. ‘Put your right foot down a quarter of an inch.’

I responded.

He pressed a black button and a high-pitched squeal was followed by the rhythmic churn of the engine. It sparked into life and beat an eager pace, rumbling faster than any car I had ever heard. The sound alone was enough to splash adrenalin through my veins. I was at the edge of the unknown. The responsive throttle, the direct steering, the beating engine, the slick gearbox … All were built with a single purpose: speed.

My first laps were shonky; I missed gears and adjusted to the precision of the controls. Once I built up some speed the steering became intense and darty. When I ran over a bump the floor actually hit my backside, I was sitting that close to the ground. The sense of speed in a straight was pale by comparison to the corners.

The belts dug into my shoulders as I sped through the turns like a cruise missile, albeit a largely unguided one. I pushed the envelope a little further with every lap.

I overcooked it several times and spun at Copse, the fastest corner. The wall was close to the track and I sensed danger until the car miraculously pointed itself in the right direction. I pushed on.

The session ended in a flash, a million years too early. I reluctantly pulled into the pits and spotted Dad in the distance next to one of the Ray Ban-toting instructors. In spite of numerous No Smoking signs, he had a Marlboro 100 glued to his bottom lip and was clapping his four-fingered hand. He’d lost the little digit rescuing a horse.

My times equalled the track record for the car. Ray Ban man was telling my dad he should really get me into a race. The old man was clearly sold on this plan all along. We had to convince my mother, but I figured another trip around the country lanes should do the trick.

From that moment on, my sole ambition, my obsession was to race. The life I lost as a pilot was reincarnated as a racing driver. Every day from then until this morning my eyes opened to the same living dream. I wanted to be a Formula 1 champion. Nothing else mattered.

The traditional route to Formula 1, or to any top category in motor sport, was to compete in go-karts from the third trimester. I’d grown up competing in pretty much every other way, as a swimmer, on skis and getting out of scrapes at school. I had the killer instinct to win, but no experience of motor racing, and it was a major disadvantage. Not that I saw it that way.

I duly obtained a racing licence at Silverstone and found myself looking down at aggressive short people. Karting, with its performance so closely linked to weight, had weeded out the big ones.

I joined the bottom rung of the racing ladder: Formula First. It was derided as a championship for nutters and the scene of too many crashes. It was the cheapest form of single-seater racing and the best way to go about winning my way to Formula 1. Piece of cake.

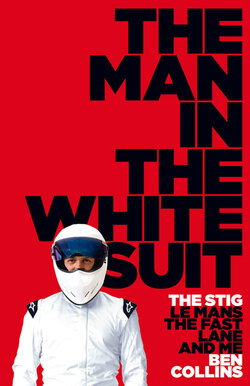

The other drivers wore colourful helmet designs and important looking racing overalls plastered with sponsors. Dad suggested I start out with something simple based on the Union Jack. In the end I opted for an all-black race suit, black gloves, black boots and a black Simpson Bandit helmet with a black-tinted visor …

From the first day I began testing the car, every waking thought revolved around a single subject: driving fast. With no prior racing experience, I learnt the trade by word of mouth, from books about great drivers like Ayrton Senna and Gilles Villeneuve, magazine articles and television. Mostly, I learned the hard way by just doing it. And shit happened.

One bit of training saved my life many times over. I attended a skid control course, which had nothing to do with brown underpants. The instructor, Brian Svenson, was a former wrestler known as ‘The Nature Boy’. He had no neck but gave plenty of it as he talked me through his Ford Mondeo, fitted with a rig that could lift the front or rear wheels off the ground to make them slide.

Every time I turned the steering, the rear would spin sideways as if it was on ice. My hands flayed at the wheel like a chimpanzee working the till at McDonald’s. Fingernails went flying, the horn was beeping, and before I knew what had happened we were sailing backwards.

Brian pressed a button on the control panel in his lap and calmly pulled the handbrake. The car came to a rest in a cloud of burnt rubber and I relaxed.

‘Oversteer, right!’ he barked.

‘OK. What does that mean?’

‘Well in that case it means the fooking car spun around, yeah. You lost the back end, so it feels like the car is turning too much. Over. Steer.’ His words sank in.

‘When it ’appens, feed the steerin’ into the slide as fast as you can. None o’ that DSA shuffling bollocks. You’ve quick reactions, just spin that wheel across a bit further.’

‘OK, Brian.’

Off we went again. My psychotic instructor pressed more buttons as we approached a tunnel of orange cones with an inflatable obstacle at the far end. I turned the steering left to dodge the obstacle and nothing happened, so I turned more.

‘Stop turning,’ ordered Nature Boy.

‘Sod that.’ I turned more. Nothing.

Whumpf.

‘Shit.’

‘You can say that again.’

‘What happened then, Brian?’

‘Understeer, right. When you turn nothin’ happens. The car goes straight on, yeah?’

‘What should I do?’

‘Not much you can do, but turning more only makes it worse. Just get the speed off then the grip comes back.’

We upped the speed to 60. After several gut-wrenching 360-degree spins, Nature Boy taught me to flick my head around like a ballerina to see where I was going and control it. It was incredible. We would enter a corner at pace and the car would start rotating. Wherever I looked, my hands would follow and the car pointed back in the right direction.

I started to complete lap after lap of the circuit, drifting from one gate through to the next. I forgot I was even carrying a passenger until the sound of Nature Boy clapping brought me back to my senses. I realised that Brian could no longer unseat me.

‘Excellent. You’ve got it. When’s your first race?’

‘Next week, at Brands Hatch.’

‘What you driving?’

‘Formula First, at the Festival.’

‘Oh Christ,’ he said, biting his top lip. ‘Good luck. Just try and remember what I’ve taught ya. If you can tell your mechanic what the car’s really doing, you’ll go far.’

Formula First was a series for ‘beginners’. The grid for my first event boasted a karting world champion, two national champions and race winners from the previous season. Most had been racing karts since they swapped nappies for Nomex. After several days of learning to drive the car at labyrinthine circuits like Oulton Park, I arrived at Brands for my first motor race.

Brands Hatch being a former Grand Prix circuit, even I had heard of this place. Formula First was supporting the Formula Ford Festival that was host to over a hundred of the best aspiring drivers in the world.

I approached my first qualifying session with the intention of re-enacting my best driving at every corner. As an inexperienced driver, just re-creating a way of driving through a corner time after time was a big challenge. It was key to posting consistent lap times. To the surprise of everyone in the championship, I qualified third on the grid.

After a short lunch break it was time for the race. I stumbled out of the Kentagon Restaurant with a bellyful of nerves and beef casserole. I was immediately accosted by a race official with a breathalyser.

I breathed gingerly into the machine. ‘Do you actually catch anyone drunk on race day?’

‘Five so far.’

I didn’t even drink, but I was apprehensive.

‘You’re all clear.’

I hurried to the pits and climbed into the car. My young mechanic straddled the top cover and heaved down on the shoulder straps with all his weight, strawberry-faced with the exertion.

After confirming that I could still breathe, he shot me a knowing smile that said, ‘One lamb, ready for slaughter.’

‘Good luck,’ he said.

I gave him a gobsmacked thumbs up. My heart rate was off the Richter scale. Wave upon wave of adrenalin hardened my veins. The back of my throat swelled, my mouth dried and the left side of my face tingled. What the hell am I doing? I was so tired. I hadn’t slept the night before and would rather have griddled my testicles on the exhaust than drive at that particular moment.

Get a grip, I thought, I’m here to get to F1. Problem was, so were the other lads.

Sweat on the pad of my left foot made my toes slip inside my boots as I depressed the clutch and nudged the gear-stick left and forward. Every movement I made felt strained and heavy.

Moving into the pit lane, I joined the two long columns of the dummy grid. After what felt like an eternity (no more than five minutes) we were waved out of the pit lane under a green flag. More adrenalin, and now I needed to piss.

The copious advice I’d been given swirled around in my head. ‘Lay some rubber on the start line for extra traction’, ‘Warm the tyres up’, ‘Anticipate the start lights’, ‘Go when the red goes out, don’t wait for the green’, ‘Don’t look in your mirrors’. After one short lap we formed up on the grid. I searched the start line gantry for the lights.

A white board with ‘five seconds’ written on it suddenly appeared from behind the gantry. Acid flooded my stomach.

Three seconds later the red lights sparked up. I knew that sometime between three and eight seconds after that they would switch to green.

The engines in front of me began revving. The driver alongside started chasing the throttle – on, off, on, off, louder and louder. Adrenalin dumped painfully into my chest and my heart slowed into a hard, raging thump. The force of the beats was so strong I had to drop my chin and open my mouth to catch a breath. I winced; my eyes glazed over. GREEN.

I bolted off the start line, then the wheels spun wildly. Another car instantly appeared to my right, then two others powered up to my left as we approached the first corner. I was jammed right in the middle.

My thumping heart slowed, crashing against my ribs with the weight of a sledgehammer. For a moment I thought the damn thing might actually stop.

I swallowed hard, gulped for air and edged into the fast sweeping right-hander at Paddock Hill. I was at the centre of a swarm of jostling machines, so close you could have covered ten of us with a blanket. Somehow my body carried on the business of driving and breathing.

The pack screamed through the dip at the bottom of the hill. The car in front bottomed out in the compression, shooting a shower of sparks at my helmet. I followed the four leaders into the tight right at Druids, narrowly avoiding the one immediately in front as he jammed on his brakes earlier than I expected.

Gears changed on auto-pilot, iron-clenched fists dragged the steering from one direction to another. We blasted through the fast Graham Hill left-hander line astern, like a rollercoaster without rails.

Wheel to wheel, nose to tail, we hammered along the short straight at nearly 100mph. As we sped into the Surtees Esses I was so close to the guy in front I couldn’t see the raised kerb past his rear wheels. My jaw clamped shut.

I somehow braked for the final corner, the right called Clearways. I went in too fast and lost control of the front wheels. I knew I’d lose a position if I couldn’t accelerate on to the straight. I forced the throttle to try and drive out of the mistake. The car was already past the limit and the rear snapped sideways. Already off line for the corner, I slid off the edge of the track into the gravel trap and towards the welcoming tyre barrier.

As the wall approached I pushed harder on the accelerator, peppering onlookers with stones from my spinning wheels but maintaining enough speed to get back on to the circuit. Having lost just one position, I rejoined the pack and we buzzed down the pit straight to complete the first lap. I was exhausted.

During the eleven laps that followed spectators were agonised and baffled by the sight of me driving defiantly on the racing line as my competitors drove for the inside, time and again, in a bid to overtake me.

My father choked his way through two packets of Marlboro in the space of twenty minutes, lighting each fresh fag from the last. Every time I came round he was shouting at the top of his voice, ‘Defend, defend, DEFEND YOUR LIIIINE!!!’

I heard nothing over the din of the engine. I was busy driving as fast as I could. Moving off line to defend meant driving slower and that didn’t compute. I stayed persistently wide, braked as late as I dared and aimed at the apex of the corners like a missile.

I was oblivious to most of my near misses, but Dad had a bird’s eye view as the other vultures pecked at my heels. Our wheels were interlocking at over 100mph and a single touch would have easily catapulted me into the air.

By some miracle, I finished unscathed having conceded a handful of positions. One of the spectators was a journalist called Charles Bradley, who had observed my antics from Clearways corner. A shard of flying gravel had cut his cheek, but he still gave me my first mention in Motor-sport News: ‘Ben is frighteningly fast …’

I was intoxicated. I’d lived more in twenty minutes than in the rest of my life put together. The time that passed between races was just that, time passing. I dreamt racing, day and night. All my aspirations now centred on becoming the best driver in the world. After a couple more races, I managed to lead one, but was harpooned out of contention by the second-placed car – yet again I’d failed to defend the corner. But the taste of potential victory was firmly entrenched. I decided I should win every time from then on. In blinkered pursuit of that goal, I discovered ever more inventive ways to have enormous accidents, from silly shunts to full-blown hospitalisation.

On the Brands GP loop, I tried to outmanoeuvre two drivers by speeding around the outside of both into the super-fast Hawthorn right-hander. The guy on the inside squeezed the one to his left who did likewise and shoved me on to the grass at 120.

I hit the Armco with such force that my head would have hit my knees had the dashboard not intervened. We never found the front left wheel, but the whole front right corner went into orbit and landed on the straight in front of my team-mate. On the second bounce it took the sidepod clean off another car, then bounded into the trees.

I finally came to rest a few hundred metres down the track, regained consciousness and slowly opened my eyes. I was coated with bright green algae that inhabited the gravel trap. Like Bill Murray in Ghostbusters, I’d been slimed. The car now resembled a bathtub, a bare chassis with a single wheel loosely attached by some brake cable. My dense cranium had even broken the steering wheel.

Over time, I broke every component of the car from the drive shafts to the suspension, gearbox, engine, chassis, everything. I once tried to find a little extra power in a drag race to the chequered flag. I pushed harder on the accelerator, which broke the solid cast metal throttle stop and ripped the throttle cable out of the carburettor.

After I wrote off my third chassis, it was clear that the ‘balls out’ strategy needed fine-tuning. During qualifying at Lydden Hill I was on the limit through a fast right when I had to lift off to avoid a spinning car. Seconds later, I was spiralling through the air and sitting in a bathtub again.

Dad sprinted to my side, absolutely livid. Not only was he funding this enterprise, but it would have been his neck on the block if I’d been converted into a limbless corpse. I couldn’t make the race, so I climbed into his car for a very long, silent drive home.

I knew he was pissed from the way he was twiddling his sideburns. After half an hour he said, ‘What the fuck were you doing waving your arms around like that anyway? You could have lost an arm.’

‘I was just ducking …’

He shot me an incredulous look.

‘I’ve just had to buy that car you trashed. If they can’t bend it straight, your season’s over.’

It was my much needed wake-up call. It seemed I had an answer for every catastrophe, but no sense to avoid one. I had to preserve the car, only risking it in measured bursts when absolutely necessary.

A part-time job in a warehouse packing cheddar cheeses the size of breeze-blocks provided plenty of opportunity to analyse past events. I spent the rest of my time hanging out with my newly acquired girlfriend and practising essential driving skills in her Ford Fiesta. Georgie was a bit special in more ways than one. She could do a handbrake turn and spin the wheels at the same time. It was love at first sight.

I figured out that even if I was the best driver on a given day, I would never win every race because there were too many circumstances beyond my control. My problem was, I’d been forcing it. Every race had a natural order, a structure I had to respect and learn to predict. Once I accepted that, the frequency of my visits to the podium exceeded those to the infirmary.

I was totally focused on learning the craft. My body began reacting like an alarm clock, ‘going off’ weeks in advance of a big race. I prepared my logistics ahead of time, drove the track a million times in my head.

My naïve concept of sportsmanship took a hammering at Castle Combe. I learnt the ropes the hard way from my ‘team-mate’, a Formula First veteran who led the championship. He had a nose like a beak that found its way into my side of the garage whenever anything worthwhile was going on. Then it was all smiles, which front rollbar was I running, what tyre pressure worked best and so pleased to meet you, Mr Potential Sponsor, here’s my card.

Later the same day I was leading him through a very fast corner on the last lap. He poked his nose up my inside but I held strong on the outside. He couldn’t get through, and it felt like he steered into me and punted me off.

I slid across the grass like a demented lawnmower and rejoined to finish fifth, just behind him. A crimson haze descended over me, but I managed to resist the temptation to T-bone him on the way into the pit lane, drag him from the car and use my helmet on him as a baseball bat.

The next race was at Cadwell Park, the best track in Britain, with more pitch and fall in its curves than Pamela Anderson. I had terminal understeer in qualifying and ended up running behind my ‘mate’ in third place, but I had my evil eye on him. I drove the wheels off my machine and discovered the power of controlled aggression. The car bent to my will and unleashed a furious pace. The closer I got to my old pal, the more mistakes he made. We approached a section called ‘The Mountain’ where an S bend climbed a steep gorge and before I had the pleasure of dispatching his ass personally, he spun off the circuit. Good karma.

Motor sport was dog eat dog, which went against the grain after five years making friends for life in the process of surviving boarding school. Popularity in racing lasted as long as you were competitive, and people were prepared to go to any lengths to remain so. I found one driver stealing my engine one night; another team sabotaged my suspension. But there were always a few rays of sunshine.

The final race of the year was at Snetterton in Norfolk, which had been a Flying Fortress base in the Second World War. Two giant straights connected two lurid high-speed corners and a couple of slow ones. I managed to get the team’s senior mechanic on to my car. Colin was a grey-haired Lancastrian who’d won the championship with my team-mate. He had eyes like Master Yoda and talked me through what to do if and when I was in a position to actually win.

‘Around this track the last thing you want to do is lead the final lap. Whoever is in second will draft past the leader on the back straight unless you slow down, so don’t get stuck out in front or … Jeezus Chriist!’

Colin’s gaze suddenly disappeared some way over my shoulder. ‘Look at ’er, she’s gorgeous!’

Still grappling with his advice, I looked to up to see the blonde bomb-shell swinging down the pit lane. Glimpses of her perfectly sculpted figure appeared from beneath a leather bomber jacket as she swished back her hair and beamed in our direction.

‘That’s my girlfriend, Georgie.’

‘You must be jokin’!’

He had a point. I couldn’t quite believe it myself.

I’d met her when we were seventeen and she took my breath away. I fell in love with her on Day One – she has one of those smiles that make you feel like the six million dollar man. My mates and I were all horrid little oiks who spent our whole time playing rugby and pouring buckets of water on to girls’ heads as they walked beneath our windows, so I didn’t give much for my chances. But a few months ago I’d somehow summoned the balls to invite her to a racing dinner – a very glamorous affair (not) at Brands Hatch’s onsite hotel – where she won a tyre trolley in the raffle. She seemed to enjoy watching my car come back with fewer wheels with each successive contest. I can’t think why; she was far too attractive and kind to be with me. When she entered a room my mouth filled with tar, reducing my vocab to Neanderthal grunting. Yet here she was looking lovely and looking at me, but …

‘What do you mean – slow down to win?’

‘Rule number one: to finish first, you must first finish, right? With these cars you sit two car lengths behind the ones in front to catch their slipstream and draft past ’em on the straights. If you get one on yer tail, back off into the corner so he can’t get a run on ya.’

I shared my newly acquired wisdom with Georgie over lunch. She was riveted. ‘So does that mean you won’t crash in this one?’

‘I hope so,’ I sighed.

The race that followed was a drafting masterclass. I became embroiled in a four-way scrap for second place whilst the leader ran away. Against every instinct, I backed off through a flat-out bend to put some space between me and the three cars in front. I braked slightly early for the next corner, Sear, then smashed the accelerator.

I hauled up behind the guy in front as he zigged left to overtake the other two running line astern. I stayed put and felt the suction of the two-car draft propelling me down the straight.

Whilst the relative speeds of the other three cars hardly changed, mine doubled. I pelted past all three in one move. I was fully clear as I approached the Esses corner and was so excited I nearly forgot to brake.

The leader was too far ahead to catch but I summoned the fury I found at Cadwell and strained every bit of speed out of my black bullet. I closed in on the final lap but not enough to pass, until he made a mistake at the final bend. I powered out of the chicane and we raced to the line. I won it by one tenth of a second.

Crossing the line first meant the world to me. And I’d learnt some key truths about the sport. Had I forced my overtaking moves early on, I would have crashed. Had I not driven flat out through every corner of every lap, I would have lost the crucial tenth of a second needed to win. It was a delicate balance, knowing when to risk everything and when to hold back. Luck had been a factor, but at least I had started making my own.