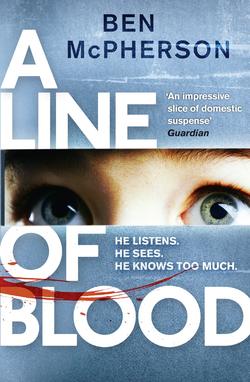

Читать книгу A Line of Blood - Ben McPherson - Страница 10

2

ОглавлениеMillicent’s side of the bed was empty. We had lain for hours without speaking, neither of us finding sleep. Then she had reached across for my hand, encircled my legs with hers, and held me very tightly. I had felt her breasts against my back, her pubic bone against the base of my spine, and I’d wondered why we rarely lay like this any more.

After some time, Millicent’s breathing had slowed and her grip loosened into a subtler embrace. I became more and more aware of her pubic bone, still gently pressing against me. But at the first stirring in my penis I remembered the neighbour’s half-erection in the bath. I stretched away from her, and she went back to her side of the bed.

‘Millicent?’

‘Mmm.’

‘Can we talk?’

‘Tomorrow,’ she had said.

Now I got up and dressed in yesterday’s clothes. I opened the door to Max’s room for long enough to see the calm rise and fall of his chest. Asleep. Clothes folded. Toys in their place. I watched him for a while, then went downstairs. Three minutes past six.

The cat tripped into the living room, tail high, limbs taut. She danced around my feet, and I reached down to her.

‘Hello, Foxxa.’ She sniffed approvingly at the tips of my fingers; then she pushed on to her hind legs, running her back upwards against the palm of my hand, forcing me to stroke her. For a moment she stood, unsteady, looking up, eyes bright and wide, as if surprised to find herself on two feet. Then she lowered herself on to all fours and wove a figure-of-eight around my calves, catlike again.

A mug on the living-room table: Millicent had drunk coffee in front of the television. I saw that the front door was unlocked, and found the kitchen empty. The cat followed me in, ate dried food from her bowl.

Millicent had left a folded note.

Alex,

We need to

talk Max (3)

talk school (1)

talk shrink (2)

talk police (?)

But please, none of this before we speak.

M

The coffee-maker was on the stove, still half-full. I checked the temperature with my hand. Warm enough to drink. I stood on the countertop and felt around on top of the cupboard, just below the plaster of the ceiling. Marlboro ten-pack. I took one and replaced the packet.

We had started hiding cigarettes from Max. He didn’t smoke them, as far as we could tell, but a pack left lying on the kitchen table would disappear. Millicent was certain that he sold them, but Max disapproved of our smoking with such puritanical disdain that I was sure he destroyed them.

In the garden I pulled the love seat away from the wall and drank my coffee, smoked my cigarette. On a morning like this, Crappy wasn’t so bad. No dogs barked, no one shouted in the street, no police helicopters watched from above. We should sort out the garden though. The garden was a state.

I stood on the love seat, looked back over the wall. Poor man, with his trimmed lawn, his verdant bower and his successful suicide attempt. From here there was nothing – nothing – that betrayed our neighbour’s sad, lonely death.

I pushed the love seat back against the wall and stood up, finished my cigarette, tried to plan the day. Quiet word with the teacher. Phone calls to the shrink. The police, I imagined, would make contact with us.

What had Max seen? When he had climbed the stairs behind me, what had he seen? That jolt, that first image, that’s what stays with you, isn’t it? Contorted face or pitiful erection? Rictus or dick? Which would be more traumatic for a boy of his age?

I flicked my cigarette butt over the wall and went back into the house. Max was in the kitchen, all pyjamas and tousled hair, rubbing sleep from his eyes. I bent down to hug him. He sniffed dramatically.

‘You’ve been smoking.’ But he threw his arms around my neck and hung there for a moment, then sat down at the table. I searched his face for some sign of something broken in him, but found nothing.

‘Max.’

‘Yeah.’

‘I’m going to be coming with you to school today. I need to tell your teacher what you saw.’

‘His name’s Mr Sharpe.’

‘… to tell Mr Sharpe what you saw.’

‘You forgot his name, didn’t you?’

‘Max. Can you listen?’

‘What? And why do you have to tell him?’

‘Because what you saw was very upsetting.’

‘It wasn’t.’

‘You might be upset later.’

He shrugged. ‘Can I be there when you tell him?’

‘Sure. OK. Why not.’

I kept expecting the police to knock on the door. Typical of Millicent to be out at a time like this.

I made a cooked breakfast to fill the time before we left. I let Max fry the eggs, which surprised him. It surprised me too. We ate in silence, then shared Millicent’s portion, enjoying our guilty intimacy. Max went upstairs. I put the plates and pans in the dishwasher and set it running. Millicent didn’t need to know.

Max came downstairs, dressed and ready to go. I texted Millicent to say I was taking him to school.

There was a man standing outside our house. He was casually dressed – leather jacket, distressed jeans – but there was nothing casual about his stance. Perhaps he had been about to knock, because the open door seemed to throw his balance slightly off. Max had flung it wide, and there stood the man in front of us, swaying, unsure of what to say.

‘Who are you?’ said Max. ‘Are you a policeman?’

The man nodded, ran the back of his hand across his mouth. He carried a briefcase that was far too smart for his clothes.

‘I could tell you were,’ said Max. ‘Are you going to arrest someone?’

The policeman ignored the question. ‘Mr Mercer?’ he said. I nodded, and he nodded at me again. He told me his name, and his rank. I immediately forgot both.

‘You got a minute?’

‘I was going to take Max to school.’

‘It’s OK,’ said Max. ‘I can just go.’

‘I’d like to speak to your son actually, if that’s all right. With your permission, and in your presence.’

No.

‘My name’s Max,’ said Max.

I looked at Max. You want to do this? He nodded at me.

‘OK,’ I said.

‘You’re giving your consent?’

‘I am,’ I said, ‘yes.’

‘Me too,’ said Max.

The policeman explained that this was not an interview, although he had recently been certified in interviewing children. He gave me a sheet of paper about what we could expect from the police and how to make a complaint if we were unhappy. Then he took out a notebook. I handed the paper to Max, who read it carefully.

First sign, I thought. First sign that this is taking a wrong turn and I end it and ask him to leave. He’s eleven.

I brought a chair in from the kitchen for the policeman. Max and I sat on the sofa. The policeman asked me where Millicent was, and I told him she was out. He asked me where she worked, and I said that she worked from home. He asked me where she was again. I said I wasn’t sure.

He made a note in his notebook.

‘She often goes out,’ said Max. ‘Dad never knows where she is.’

‘Max,’ I said.

‘Well, you don’t.’

The policeman made a note of this too.

‘Mum values her freedom.’

The policeman made yet another note. Then he took out a small pile of printed forms on to which he began to write.

‘How old are you, Max?’

‘Eleven.’

‘And is Max Mercer your full name?’

‘Yes. I don’t have a middle name.’

‘And you’re a boy, obviously.’

‘Obviously.’

They exchanged a smile; I realised that the policeman was simply nervous.

‘Can I sit beside you?’ said Max. ‘Just while you’re doing the form?’

The policeman looked at me.

‘If that’s OK with your dad.’

‘Sure,’ I said. I asked him if he wanted a coffee; he asked for a glass of water instead. I went through to the kitchen. Was he nervous, I wondered. Or are you playing nice cop?

‘I’m white British,’ I heard Max say, ‘even though British isn’t a race but the human race is. We’re not religious or anything. And my first language is English, so I don’t need an interpreter.’

He was reading from the form, I guessed, checking off the categories: so proud, so anxious to show how grown-up he could be. ‘For my orientation you can put straight.’

‘That’s really for older children,’ I heard the policeman say.

‘But can’t you just put straight?’

‘All right, Max. Straight.’

I came back in with the water. The policeman got up and sat opposite us again in the kitchen chair, writing careful notes as his telephone recorded Max’s words.

‘What were you doing before you found the neighbour, Max?’

‘Not much. Like reading and homework and stuff. I’m not allowed an Xbox or anything. And Mum was out, and Dad was working. He lets me borrow his phone, though.’

The policeman sent me an enquiring look. Then he made another note. I was wrong. It wasn’t nervousness; it was something else. There was a shrewdness to him that I hadn’t noticed at first, and that I didn’t much like. ‘We’re good parents,’ I wanted to say to him. ‘We love him unconditionally. We set boundaries.’ Don’t judge us.

He was good at speaking to children, though: I had to give him that. Max told him everything. That we had been looking for our cat, that the cat had led us into the neighbour’s house, that the back door had been open, and that the cat had disappeared up the stairs.

‘Is it better to say erection, or can I say boner?’ said Max.

‘Just say whichever you feel more comfortable saying,’ said the policeman.

‘But what should I say in court?’

‘I don’t think you’re going to have to speak in court,’ said the policeman. ‘That’s very unlikely.’

‘What would you say, though?’

The policeman laughed gently. ‘Probably erection. It’s the official word.’

‘OK.’ Max smiled a wide smile. ‘Erection.’ Then he became serious again; he made himself taller and stiffer, an adult in miniature. ‘Anyway, even though Dad tried to stop me seeing, I saw that the neighbour had an erection.’

I hadn’t tried to stop Max from seeing, though. At least I didn’t think I had. I was suddenly unsure. Perhaps I had.

‘I’m sorry, Max,’ said the policeman. ‘That must have been upsetting for you.’

‘You don’t mean the erection. You mean the dead body.’

‘Yes,’ said the policeman.

‘It was OK,’ said Max. ‘I mean, it wasn’t nice, but it was OK. Have you seen a dead body before?’

‘No,’ said the policeman, ‘only pictures.’

‘Isn’t it your job?’

‘We all have slightly different jobs,’ he said.

‘How long have you been a policeman?’

‘Couple of years,’ he said.

I had been wondering whether to send Max upstairs to his bedroom, or to ask whether I could drop Max at school and then come back. Of course, Max could have walked to school by himself, but I wanted to walk by my son’s side, to see him safely there, to make sure he was OK after the questions from the police.

The policeman didn’t need to speak to me. He had other children he had to speak to. Formal interviews.

‘Dark stuff,’ he said, and a troubled look clouded his features.

‘What dark stuff?’ said Max.

The policeman checked himself again. He stood up, put the forms in his briefcase, and handed me a card, told me his colleagues would be in touch to speak to me.

‘What dark stuff?’ said Max again.

‘Not all parents love their children the way your dad loves you, Max.’

As we left the house Max slipped his fingers through mine. Little Max, my only-begotten son. He hardly ever held my hand these days.

‘Dad,’ said Max, ‘Dad, Ravion Stamp had to go to the police station, and they filmed it and everything. And his dad wasn’t allowed to be there.’

‘That isn’t going to happen to you,’ I said.

‘But what if they arrest you?’

‘Why would they do that?’

‘But Ravion’s dad …’

Jason Stamp had violently assaulted his son. Ravion had testified by video link. I wasn’t sure how much Max knew about the case.

‘That won’t happen to us, Max. I promise you.’

‘But how could that man know that you love me?’ he said.

‘He could see it.’

‘How?’

‘OK, he was just guessing.’

‘You are so annoying, Dad,’ he said. But he leaned in to me and wrapped his arms around me for a moment. My beautiful, clever son. My only-begotten. Whose first word was cat and whose seventh was fuck; whose forty-fourth word was a close approximation of motherfucker.

Forget the swearing, though. We fed Max, we clothed him, we sang him to sleep at night. We set clear boundaries, and applied rules as fairly as we could. Our house was full of love. We are the classic good-enough parents.

Millicent and Max would bath together; I would hear their shrieks of laughter from halfway down the street. Listen to that: that’s the sound of my little tribe. Listen to that and tell me it’s not real.

Yes, we swore in front of Max, and yes, we smoked behind his back. That doesn’t matter. What matters is this – my wife, my son, the water and the laughter.

My little tribe.

Max let me hold his hand until we neared the school, then slipped his fingers from mine, walked beside me. On the final approach, he half-ran, putting ground between himself and me, anxious not to be seen arriving with a parent.

Millicent rang. I cradled the phone to my ear. Screams and shouts of morning break, six hundred London children giving voice.

‘I was worried.’

‘Hey. Sorry.’ Her voice was strained.

‘Where are you?’

‘On my way. You at the school?’

‘Yes.’

‘Wait for me?’

‘I’d hoped to speak to him before they go in again.’

‘You’ve forgotten his name again, haven’t you?’ Her voice softened.

‘I know. Bad Dad.’

‘So, you going to wait for me, Bad Dad?’

‘OK. All right.’

I saw Max in a dissolute huddle of boys, all oversized shirts and falling-down trousers. I caught his eye and pointed to the school building. ‘See you in there,’ I mouthed. He nodded and turned away.

Millicent arrived five minutes after the school bell. She was pale, the contours of her face shifted by lack of sleep. She reached up and kissed me.

Even in heels, Millicent was short. When we’d first met, it had made me want to protect her. Now I hardly noticed. I held her, grateful that she was there. She held me just as tightly. Then she ended the embrace by tapping me on the back.

‘Where’ve you been?’ I said.

‘Out. Thinking. Sorry.’

It’s been like this since we lost Sarah. Millicent’s reaction – her ultimate reaction, after she had fallen apart – was to do the opposite of falling apart. She reconstructed herself. She became supercompetent. Make your play, she writes, then move on. Play and move on.

The classroom looked like a post-war public information film, but with more black and brown faces. Didactic posters covered the walls. The children sat in orderly rows, working in twos from textbooks. Three rows back sat Max with his friend Tarek. He looked up when we entered, but didn’t acknowledge us.

Mr Sharpe too looked like a man from another age. Dark-skinned, and with close-cropped hair, dressed in a faultlessly pressed suit: like a black country schoolmaster from a time when no country schoolmaster was black. His hair was brilliantine slick, his moustache pencil thin, his hands delicate and agile.

‘May we speak with you?’ Millicent said. ‘We’re Max’s parents. We wanted to explain the reason for his lateness.’

‘Of course.’

‘In private.’ She turned towards the corridor.

‘Actually, that isn’t really appropriate.’ He gestured towards the class. I looked around, and found Tarek and Max looking directly at me. Tarek whispered something to Max; they looked at the teacher and at us, and laughed.

‘Unless, of course, you can wait until lunch break. Twelve fifteen. Here.’

‘We’d like Max to be present.’

Mr Sharpe nodded, waved us from the room and closed the door behind us.