Читать книгу Salt on my Skin - Benoite Groult - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление-

FOREWORD

BY FAY WELDON

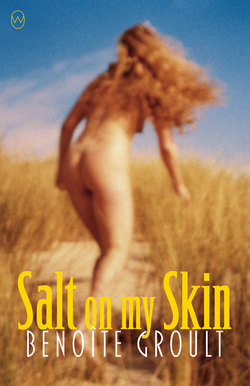

Benoîte Groult, writer, feminist, Commander (and later raised to Grand Officer) of the Légion d’honneur, born in Paris in 1920 and dying aged ninety-six in 2016, left behind this glorious novel, a paean of praise to love and lust through youth and age. Groult wrote the novel when she was sixty-seven, and Salt on my Skin was first published in 1988. It’s gratifying to see this noble classic of women’s literature now revived and honoured.

Les Vaisseaux du Coeur in its original French, Salt on my Skin in the English translation, was an instant succès de scandale, becoming a massive international bestseller, translated into twenty-seven languages. It was lambasted by some as pornographic; by others for its ‘incorrect’ feminist views—women should surely be concentrating on earning a living and withstanding male brutality, not succumbing to desire.

This latter disapproval, since Groult herself was by this time a leading feminist, must have caused her some distress: it is never nice to be accused of disloyalty by colleagues, but Groult’s own experience of the joys and pains of physical love was too strong and urgent not to be told. And so she told all: to the great benefit of today’s young women, so many condemned to endure the sensually arid world of the new gender-reversed millennium in which sex is recreational rather than sacramental, lust is seen as a weakness rather than a strength, love as a neurosis damaging to a woman’s self-interest, men are relegated to the merely decorative, and husbands are an optional extra in a long, long life.

With a lifetime of experience and lust behind her, Groult, in this great, rich, energetic, intelligent, imperfect novel, reminds us that a woman’s life may be otherwise, that lust and love can enhance and enrich, rather than diminish her.

Salt on my Skin traces the course of a love affair between an intellectual Parisienne (George, as in George Sand) and an uneducated Breton fisherman, Gauvain. All starts when she is eighteen—“in that silent half-sleep, I felt our deepest beings embrace, refusing separation”—and ends with Gauvain’s death at fifty-seven: “I was shivering in spite of the mild weather. As if my entire skin was in mourning for him.” In the beginning the lovers part—“my heart full of tears, my mind full of logic,” but simple longing, overcoming practical and social problems, brings them back together. Though they each marry within their own milieu, the affair between the ill-assorted couple continues for decades. A particular skin touches a particular skin—and class and cultural difficulties melt away. Well, almost; in the end, though only after decades, these are too great to overcome.

In the meanwhile, George’s husband is complaisant, though Gauvain’s wife is not. George is guilt-free. Gauvain suffers guilt, and George thinks the more of him for it. “He was a good person,” George’s inner chaperone (her intellectual, reproachful, observing self) is able to say. “I’m not so sure about you [George], but he was a good man.”

Salt on my Skin is more than just a simple love story or it would not have received the attention it did. Groult drops pearls of wit and worldly wisdom behind her as she goes. “One missing tooth makes you look like a buccaneer, two and you’re a grandad!” She acutely traces the bodily changes that age makes. “He no longer made love as if devouring a feast or champing at the bit or, simply, drawing breath. Now he flung himself on it, as if plunging into water or trying to get drunk or taking revenge.” And she in her turn regrets the passing of youth: “When you’re twenty you want everything, and you’re right to have high hopes. At thirty you still think you can have everything. At forty it’s too late. It’s not that you’ve aged, it’s hope that’s aged.” (Thirty years later, in a health-conscious age, we stay younger longer, so we can add another decade to each category.) Groult is as devilishly accurate in her account of going to the hairdresser as she is about the problems of the monthly bleed.

Four Three times married herself, three children, twice widowed, sexually and intellectually energetic, a passionate defender of women’s rights, and greatly loved by family and friends, there is little Groult has not experienced, noted, and being so generous in spirit, passed on. Her writing appeals to the universal woman in us all, acknowledging our wrongs, but all too conscious of our weaknesses.

An earlier non-fiction book, Ainsi Soit-Elle (translated as As She Is) was published in 1975, and confirmed Groult as a leading feminist as well as novelist. Feminism, mind you, came late to France. Whereas the vote in the UK came in 1918, after the First World War; it did not come to France until 1945, after the Second. France, a strongly Catholic country, traditional in its ways and customs, saw little need for such absurdities. But the publication in 1949 of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (“One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman,” she argued) shook male complacency. A low-level female indignation then smouldered away until around the time of the publication of Ainsi Soit-Elle in 1975—the same year Helene Cixous published The Laugh of the Medusa, debunking Freud’s theory of ‘penis envy’, which had kept women in their place for so long. Groult explored the history of women’s rights and the violence against women created by a generalised misogyny. After that a more active, less intellectual feminism flared into life. Ainsi Soit-Elle was also an international best seller and Groult, at the age of fifty-five, became a leading light of the Women’s Liberation movement.

The publication of her novel Salt on my Skin some ten years later, all about the sensual pleasure and sexual delights of an adulterous couple, seemed more in keeping with the strand of écriture féminine than with second-wave feminism, and it shocked many. Even in an age when porn is part of the social landscape, when women often earn more than men, and sophisticated young female executives can take up with Balinese fishermen and live, or claim to, happily ever after (who wants city life and good conversation when sensuous sex, sun, and sand are only an air-flight away?) Groult’s Salt on my Skin still makes one feel as if one is stepping into unknown and possibly dangerous waters, where unwelcome immanent truths may lurk.

Nothing escapes Groult’s keen eye. Her observations are acute. On the insistent individualism of the French: “their unconcern, their lack of civic spirit and their skill at turning professional rivalries into an art form.” On the blonde hair and blue eyes of the American beauty: “With her blonde hair and blue eyes, she had that milk-fed, corn-fed, steak-fed air. Vitaminised and psychoanalysed to the core, she saw comfort and health as her right, and unhappiness as an illness.” And with equal insight she examines the ambivalent feeling a woman has about the texture of the male scrotum, and the way the male penis feels, “not hard like wood, not even like a cork, say, but hard and soft at the same time, like nothing else in the world but another penis in a similar state of arousal.”

Of course the novel is imperfect, as a long book written with such passion and integrity is almost bound to be. Sometimes (as Groult attempts to break free from the conventional reticences that have plagued écriture féminine from the beginning) the many detailed descriptions and the determined naming of the parts involved in the sexual act can seem excessive and slightly embarrassing. Some might criticise the way Groult changes rather indiscriminately from first to third person singular—sometimes we’re seeing the world through George’s eyes, sometimes without warning through the writer’s—but to my mind this serves to make the reader’s involvement with the story closer and more intimate. George becomes both the observer and the observed.

Unusual and unlikely coincidences bring the lovers together—how does a Breton fisherman just happen to be trawling for tuna in Dakar and just happen to run into George? The reasons given can become rather forced. Indeed, considering both lovers are French why does the US seems to be where much of the novel takes place?

But all becomes clear when one realises that Gauvain, the uneducated Breton fisherman of the novel, was in real life Kurt, a poorly educated American pilot. Quicker by far to get around the world by plane than by Breton fishing trawler!

Blandine De Caunes, Benoîte’s daughter by her second marriage, reports that she and her sisters, Lison and Constance, knew of their mother’s affair and became very fond of Kurt. When later, after splitting with her second husband, Georges de Caunes, Benoîte was in an ‘open’ marriage with writer Paul Guimard—who, like Gauvain loved the sea: the surging ocean looms large throughout the novel—Kurt was a frequent visitor to their home in Ireland. Paul kept out of the way when Kurt visited, but as de Beauvoir found in her marriage to Sartre, when theirs was the very one which made such relationships fashionable, ‘open’ marriages are never easy. Love and jealousy, however much dismissed theoretically, keep intruding.

Salt on my Skin is built around not just the known diaries that Benoîte Groult began in 1945 when she was twenty-five, but also on secret erotic diaries she’d written as an adolescent back in the thirties. By the late forties the men were back from the war, and women, being back in the home, were dependent again on male goodwill for their livelihood, so sexual reticence was more than ever advisable. Many, no doubt, were the secret diaries written at that time. Once a woman was married, Groult pointed out elsewhere, the need for secrecy was even greater: “When the ‘oppressor’ is your lover and the father of your children and often the principal purveyor of the funds, freedom becomes a complex and risky undertaking. So much so that many women prefer security, even under supervision, to the hazards of freedom.” It was a good thirty years before women could earn, and no longer requiring male approval, could write the truth of female experience.

The affair in Salt on My Skin is moved forward a couple of decades and set between the fifties and the eighties. What Groult has presumably sourced from the secret diaries in which she recorded its early days is material which seems to me barely fictional—written in the first person by a talented young writer with such great tenderness it’s hard to imagine a more stirring or romantic evocation of a girl’s sexual awakening: a female Bildungsroman.

Blandine, asked in an interview what her mother, good feminist to the end, would say by way of advice to young women writers, suggests: “Don’t get married, it’s not worth divorcing. Stay free and write what you want, in words that are yours.” Though, as Blandine, herself a writer and editor, adds: “Many women would find that advice difficult to follow, even today.”

I find myself recommending the book to friends in emotional trouble, saying what I said in the seventies of Marilyn French’s The Woman’s Room: “Read now, at once! This book changes lives.” But Salt on my Skin is a far more positive and less angry novel, as befits the current times.

FAY WELDON / 13th June 2018