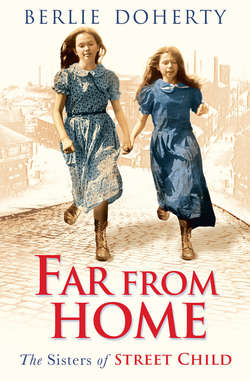

Читать книгу Far From Home: The sisters of Street Child - Berlie Doherty - Страница 16

Оглавление

Rosie and Lizzie had stopped running by now. They were well away from the Big House, and Rosie knew that Lizzie would never find her way back there on her own. She drew her under a bridge to rest a little, and let go of her grasp. Gulls screeched mournfully, the tide was out, the riverbanks were a stinking mess of mud and fish bones and rubbish. Further down the river they could see a huddle of fishermen’s cottages, clustered together like a mouthful of rotting teeth.

“That’s where I come from,” said Rosie. “That’s where I was born. Went up in the world, I did, thanks to your ma.” And now it looks as if I’m sunk back down, just like that, she thought to herself.

Lizzie thought the cottages looked even worse than Mr Spink’s tenement house where she used to live with Ma and Emily and Jim. How long ago was that? Only three days? And where was Ma now? Where was Jim?

“Is that where you’re taking me?”

“Oh no. My granddad would eat you up. Like a snappy dog, he is. He’s wicked. I wouldn’t take you there. No, Lizzie, we’re going to Sunbury.”

“I want to go back to Emily. Back to the Big House.”

“Well, you can’t,” Rosie said firmly. “We’ve been kicked out. There, now you know, and I wasn’t going to tell you that. We’ve got to go to Sunbury, or starve, and that’s the truth. It’s our only hope now. My sister might speak for us. We’ll be all right there, maybe. But we’re going to be walking till our legs drop off, so best get a move on. Up that lane now.”

It was beginning to drizzle with a sharp, frosty sleet. Rosie stopped to pull her shawl up over her head. I wish I was back in that big warm kitchen, she thought. The job of my dreams, that was, working there. Never again, Rosie. Not for you.

“What’s that big building up there, with the black railings?” Lizzie asked. She had a feeling that she knew very well what it was, that it had been pointed out to her in the past as a house to be afraid of, a last-place-in-the-world sort of house, more frightening even than a graveyard.

“It’s the workhouse,” Rosie said. She tugged Lizzie’s arm, anxious to hurry past the place, but Lizzie pulled herself away from her.

“I want to go there. If I can’t go back to the Big House, I want to go there.”

“Not there! I won’t let you.”

“But Ma might be there. And Jim. I want to be with them.” Lizzie was already running up the middle of the slippery road, and all Rosie could do was to lift her skirts out of the muck and run after her. Maybe, she thought fleetingly, it would be for the best. In her heart of hearts she knew that her sister would never be able to find work for both of them, probably not even for one of them. At least if Lizzie was in the workhouse she would have food of sorts, and a roof over her head. She wouldn’t be sleeping on the streets like the other homeless children. But the nearer she drew to the huge iron gates that kept the inmates of the workhouse away from the rest of the world, the more her dread and fear of the place grew.

Never, she thought. I’ll never let Annie’s child go there.

Lizzie had nearly reached the railings when she saw a group of children being herded out of the door into the workhouse yard. A boy ran ahead of the others and stood clutching the railings with both hands, his white face peering out through the bars.

“Jim! It’s Jim!” Lizzie yelled, slipping down on the greasy cobbles in her eagerness to get to him. But when the boy turned his head to look at her she could see that it wasn’t her brother at all. He stuck his hand through the bars.

“Got any bread, miss? Got some cheese?”

“Do you know Jim Jarvis?” Lizzie asked him. “Did a boy come here with his mother, and she was sick and weak and he probably had to help her to walk – did you see them?”

The boy looked puzzled. “A boy and his ma?”

“Did you see them? She’s Mrs Jarvis. Annie.” Lizzie looked over her shoulder anxiously. Rosie had nearly reached her. “He’s called Jim. He’s my brother.”

“Jim Jarvis?” the boy repeated. “Jim Jarvis and his ma?” As if it was part of a nursery rhyme that he was trying to remember.

As soon as Rosie reached them she fumbled in her bag and brought out a hunk of cold pastry that she had saved from last night’s supper. It was meant to keep them going on their long walk to Sunbury. She held it out towards the boy and as she did so, she shook her head very slightly, and narrowed her eyes, and made her mouth into the silent shape of “no”.

“No,” said the boy quickly. “No Jim Jarvis here.” He snatched the crust and ran to join the other children who were being hustled towards the gates by the ancient workhouse porter.

“Stand ’ere and wait till the coach comes,” the old man was saying to them. “And thank the Lord you’re going to a better life. Is that Tip?” he shouted to the boy. “What you eating? Been beggin’, ’ave yer?” He grabbed the boy and dragged him away. “You ’eard what Mr Sissons said! Wait nice and quiet till Mrs Cleggins comes. No begging, no annoying, be’ave like a gentleman! Lost yer chance now, you fool.” And he dragged Tip back inside the workhouse building. The other children clustered together, giggling nervously. A tall, handsome boy grinned and raised his hand as if he was saluting as a smart carriage drew up to the gates. The waiting children cheered and surged forward.

“There you are,” said Rosie. “They’re not there, and nor will you be. It’s no place to live or die, I can tell you that.”

“No, it’s not,” Lizzie agreed. She looked at the grim, soot-blackened building and shuddered, and then turned her back on it. “I don’t want to go there. Not if Jim and Ma aren’t there. Not ever.”

“Lizzie!” a familiar voice shouted. “I’m here! I’m here!”

But it wasn’t Jim’s voice, or Ma’s. It was Emily, running up the lane from the river. “Don’t go without me!”

“Oh lor!” sighed Rosie. “Two of them now!”

“I told you I wouldn’t let you go,” Emily gasped, panting up to them. “I ran and ran, and I didn’t know where to look for you, and then I thought, the workhouse, that’s where they’ll be, and I was right.”

“Don’t tell me you’ve quit that good job,” Rosie said. “Now what?”

“I don’t care what happens now,” Emily said. “As long as I’m with Lizzie.”

“Are these girls for me?” a sharp voice called. Rosie looked round to see that a hefty, ruddy-faced woman was leaning out of the carriage window. “Homeless girls?”

“I suppose they are,” Rosie sighed. “Why do you want to know?”

“Because I’m looking for a pair of strong, healthy girls just like these two.” The woman had a strange, flat accent that was a bit difficult to understand. Lizzie watched her, fascinated, and the woman caught her eye. Her mouth twitched into a grim sort of smile that showed her brown teeth. “Got their papers? Indentures?”

A wagon drew up behind the carriage. “Get in, children,” the woman shouted to the waiting huddle, and with great excitement the children from the workhouse all climbed in.

“And you two.” The woman nodded to Emily and Lizzie. “You can send their papers on. I’m in a hurry.”

“Wait a minute,” Rosie said. “Who are you? Where are you taking these children?”

“I’m Mrs Cleggins,” the teeth clacked. “Of Bleakdale Mill. I’m here to collect homeless children, good homeless children, from workhouses and streets. I look after them, poor little mites. I give them a future! I have plenty of work for them.”

“What kind of work?” Rosie asked suspiciously. But her heart was beginning to lift.

“They’ll be apprentices. Out of kindness of his heart, Mr Blackthorn gives apprenticeships to poor and needy children They’re all going to learn to be textile workers. He gives them a new life! You’re very lucky, I’ve got room for these two today. I think in the circumstances and out of charity Mr Blackthorn will overlook the lack of proper documents. I were promised ten lads and ten lasses from this workhouse, but looks like there’s only eight lasses here.” She clacked her teeth together impatiently, then added as an afterthought, “Probably too sick or died, poor creatures. A life in country might have saved them. Don’t tell me you don’t want these lasses to come!”

“I don’t know,” Rosie said doubtfully. “I promised their mother I’d look after them.”

“Well, they’d have a lovely life with me. Fresh country air, good country food, and a job for life. Make your mind up, I can’t dally all day.”

“They’d get a wage, would they?”

“Naturally. And clean clothes. Oh, put them inside wagon. They’re hardly dressed for this rain. I cannot bear to see them shivering like that.”

“I don’t know what to say.” Rosie turned away. “What do you think, girls?”

Emily sensed the despair in Rosie’s voice. “Maybe we could go there just for a bit, Lizzie, till Rosie finds somewhere for us all to live.”

“Would it be like when we used to live in the cottage, before Pa died?” Lizzie asked. “Would we have a cow and a pig?”

“I think your lasses want to come,” Mrs Cleggins said.

“Do you really?” Rosie asked them. Her heart was fluttering. I’ve no job, I’ve no home, I’ve nothing to give them, she thought. What right do I have to deny them a promising future like this?

“It’s not fair to expect Rosie to look after us both,” Emily whispered to Lizzie. She squeezed her sister’s hand. “We’ll try it,” she said.

Rosie made a choking sound like a strangled cough in her throat. She fumbled inside the bundle she was carrying and thrust something towards Lizzie. “Here, I made this rag doll for my sister’s child. Have it, to remember me. God bless you both.”

She hugged them quickly and then hurried away so she didn’t have to watch them clambering into the wagon. She heard the doors being slammed shut behind them, heard the driver yelling coarsely to the horses to “Gerra move on, will yer!” and the snort and rumble as the carriage and wagon moved away. She turned then, one hand lifted in a wave of farewell, the other clasped to her mouth.

“There you are, Annie. I’ve done my best for your girls. Just like I promised.”