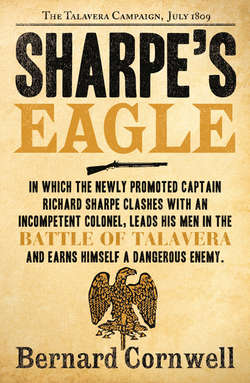

Читать книгу Sharpe’s Eagle: The Talavera Campaign, July 1809 - Bernard Cornwell - Страница 9

FOREWORD

ОглавлениеThis was the first book I wrote, and it is the only book of mine that I have never dared go back and re-read. I still do not dare, for I am sure I would be horrified by the crudity of its writing, but I am constantly told by readers that it is one of their favourites.

It tells the story of the battle of Talavera, which occurred towards the beginning of the Peninsular War. It was not where I wanted to start the Sharpe series. I really wanted to begin with the tale of Badajoz (which turns up in Sharpe’s Company), because Badajoz is such an extraordinary and dramatic event, but I decided it would be a good idea to write a book or two before Badajoz, rather like a bowler warming up before he takes on the opening batsman. I had never written a novel before, never tried to write a novel before, and so Sharpe’s Eagle is where I was going to make all a beginner’s mistakes, and where, if I was successful in my ambition to write a series of tales about the adventures of a British rifleman in the Napoleonic Wars, I was going to learn some of the tricks of the trade. One of the first things I learned was that Sharpe’s enemies, by and large, had to be British. I had thought, before I began writing, that the French would provide him with enemies enough, but the circumstances of war meant that Sharpe spent much more time with the British than with the enemy French, and if he was to be unendingly challenged, irritated, obstructed and angered then the provocations had to come from people with whom he was constantly associated. In time Sharpe is to meet many foul enemies, but few, I think, are as nauseating as Sir Henry Simmerson who, I seem to remember, becomes a tax inspector in his later career.

I said Sharpe’s enemies were British. In fact most of them, like me, are English, while his friends are often Irish. This arose from the happy fact that I had been living in Belfast in the years immediately prior to writing Sharpe and had acquired a fondness for Ireland which has never abated. It also reflected a truth that Wellington’s army was heavily recruited from the Irish, and indeed the Duke (as he was to become) had been born there. That was not a fact of which he was proud. ‘Being born in a stable,’ he once remarked, ‘does not make a man a horse.’ The Duke was a difficult, cold and snobbish man who was also one of the greatest soldiers ever to take the field. Like Sharpe I admire him, but would not particularly wish to dine with him. His story, though, is intimately linked with Sharpe’s, which is to Sharpe’s good fortune. But Sharpe, if he is to make his reputation, must do it with action, rather than by his distant connection with the Duke, and there was no act more admired on a battlefield than the capture of an enemy’s standard. In Napoleon’s army those standards took the form of small statuettes of eagles – thus the book’s title. I decided that if I was not to launch Sharpe against the great walls of Badajoz in his first adventure, then he should face another task just as impossible, and so I set him to capture an eagle. Poor Sharpe.

But there were much greater events resting on his shoulders than the seizing of an eagle. I had fallen in love with Judy, an American to whom the book is dedicated and who, for family reasons, could not live in Britain, which meant I had to earn a crust in the United States if the course of true love was ever to flow smooth. The American Government, in its Simmerson-like wisdom, refused me a work permit so I airily told Judy that I would support us by writing books. Sharpe had to succeed if that irresponsible promise was to be kept. That was twenty-one years ago, and we are still married, so in truth Sharpe’s Eagle is a dazzling romance. And one day I shall read it again.