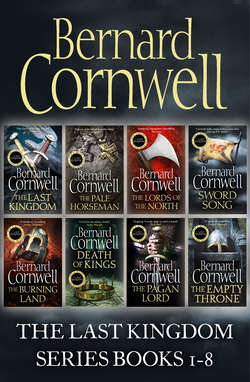

Читать книгу The Last Kingdom Series Books 1–8: The Last Kingdom, The Pale Horseman, The Lords of the North, Sword Song, The Burning Land, Death of Kings, The Pagan Lord, The Empty Throne - Bernard Cornwell - Страница 46

Seven

ОглавлениеThe kingdom of Wessex was now a swamp and, for a few days, it possessed a king, a bishop, four priests, two soldiers, the king’s pregnant wife, two nurses, a whore, two children, one of whom was sick, and Iseult.

Three of the four priests left the swamp first. Alfred was suffering, struck by the fever and belly pains that so often afflicted him, and he seemed incapable of rousing himself to any decision so I gathered the three youngest priests, told them they were useless mouths we could not afford to feed, and ordered them to leave the swamp and discover what was happening on dry ground. ‘Find soldiers,’ I told them, ‘and say the king wants them to come here.’ Two of the priests begged to be spared the mission, claiming they were scholars incapable of surviving the winter or of confronting the Danes or of enduring discomfort or of doing any real work, and Alewold, the Bishop of Exanceaster, supported them, saying that their joint prayers were needed to keep the king healthy and safe, so I reminded the bishop that Eanflæd was present.

‘Eanflæd?’ He blinked at me as though he had never heard the name.

‘The whore,’ I said, ‘from Cippanhamm.’ He still looked ignorant. ‘Cippanhamm,’ I went on, ‘where you and she rutted in the Corncrake tavern and she says …’

‘The priests will travel,’ he said hastily.

‘Of course they will,’ I said, ‘but they’ll leave their silver here.’

‘Silver?’

The priests had been carrying Alewold’s hoard which included the great pyx I had given him to settle Mildrith’s debts. That hoard was my next weapon. I took it all and displayed it to the marshmen. There would be silver, I said, for the food they gave us and the fuel they brought us and the punts they provided and the news they told us, news of the Danes on the swamp’s far side. I wanted the marshmen on our side, and the sight of the silver encouraged them, but Bishop Alewold immediately ran to Alfred and complained that I had stolen from the church. The king was too low in spirits to care, so Ælswith, his wife, entered the fray. She was a Mercian and Alfred had married her to tighten the bonds between Wessex and Mercia, though that did little good for us now because the Danes ruled Mercia. There were plenty of Mercians who would fight for a West Saxon king, but none would risk their lives for a king reduced to a soggy realm in a tidal swamp. ‘You will return the pyx!’ Ælswith ordered me. She looked ragged, her greasy hair tangled, her belly swollen and her clothes filthy. ‘Give it back now. This instant!’

I looked at Iseult. ‘Should I?’

‘No,’ Iseult said.

‘She has no say here!’ Ælswith shrieked.

‘But she’s a queen,’ I said, ‘and you’re not.’ That was one cause of Ælswith’s bitterness, that the West Saxons never called the king’s wife a queen. She wanted to be Queen Ælswith and had to be content with less. She tried to snatch back the pyx, but I tossed it on the ground and, when she reached for it, I swung Leofric’s axe. The blade chewed into the big plate, mangling the silver crucifixion, and Ælswith squealed in alarm and backed away as I hacked again. It took several blows, but I finally reduced the heavy plate into shreds of mangled silver that I tossed onto the coins I had taken from the priests. ‘Silver for your help!’ I told the marshmen.

Ælswith spat at me, then went back to her son. Edward was three years old and it was evident now that he was dying. Alewold had claimed it was a mere winter’s cold, but it was plainly worse, much worse. Every night we would listen to the coughing, an extraordinary hollow racking sound from such a small child, and all of us lay awake, dreading the next bout, flinching from the desperate, rasping sound, and when the coughing fits ended we feared they would not start again. Every silence was like the coming of death, yet somehow the small boy lived, clinging on through those cold wet days in the swamp. Bishop Alewold and the women tried all they knew. A gospel book was laid on his chest and the bishop prayed. A concoction of herbs, chicken dung and ash was pasted on his chest and the bishop prayed. Alfred travelled nowhere without his precious relics, and the toe ring of Mary Magdalen was rubbed on the child’s chest and the bishop prayed, but Edward just became weaker and thinner. A woman of the swamp, who had a reputation as a healer, tried to sweat the cough from him, and when that did not work she attempted to freeze it from him, and when that did not work she tied a live fish to his chest and commanded the cough and the fever to flee to the fish, and the fish certainly died, but the boy went on coughing and the bishop prayed and Alfred, as thin as his sick son, was in despair. He knew the Danes would search for him, but so long as the child was ill he dared not move, and he certainly could not contemplate the long walk south to the coast where he might find a ship to carry him and his family into exile.

He was resigned to that fate now. He had dared to hope he might recover his kingdom, but the cold reality was more persuasive. The Danes held Wessex and Alfred was king of nothing, and his son was dying. ‘It is a retribution,’ he said. It was the night after the three priests had left and Alfred unburdened his soul to me and Bishop Alewold. We were outside, watching the moon silver the marsh mists, and there were tears on Alfred’s face. He was not really talking to either of us, only to himself.

‘God would not take a son to punish the father,’ Alewold said.

‘God sacrificed his own son,’ Alfred said bleakly, ‘and he commanded Abraham to kill Isaac.’

‘He spared Isaac,’ the bishop said.

‘But he is not sparing Edward,’ Alfred said, and flinched as the awful coughing sounded from the hut. He put his head in his hands, covering his eyes.

‘Retribution for what?’ I asked, and the bishop hissed in reprimand for such an indelicate question.

‘Æthelwold,’ Alfred said bleakly. Æthelwold was his nephew, the drunken, resentful son of the old king.

‘Æthelwold could never have been king,’ Alewold said. ‘He is a fool!’

‘If I name him king now,’ Alfred said, ignoring what the bishop had said, ‘perhaps God will spare Edward?’

The coughing ended. The boy was crying now, a gasping, grating, pitiful crying, and Alfred covered his ears with his hands.

‘Give him to Iseult,’ I said.

‘A pagan!’ Alewold warned Alfred, ‘an adulteress!’ I could see Alfred was tempted by my suggestion, but Alewold was having the better of the argument. ‘If God will not cure Edward,’ the bishop said, ‘do you think he will let a witch succeed?’

‘She’s no witch,’ I said.

‘Tomorrow,’ Alewold said, ignoring me, ‘is Saint Agnes’s Eve. A holy day, lord, a day of miracles! We shall pray to Saint Agnes and she will surely unleash God’s power on the boy.’ He raised his hands to the dark sky. ‘Tomorrow, lord, we shall summon the strength of the angels, we shall call heaven’s aid to your son and the blessed Agnes will drive the evil sickness from young Edward.’

Alfred said nothing, just stared at the swamp’s pools that were edged with a thin skim of ice that seemed to glow in the wan moonlight.

‘I have known the blessed Agnes perform miracles!’ the bishop pressed the king, ‘there was a child in Exanceaster who could not walk, but the saint gave him strength and now he runs!’

‘Truly?’ Alfred asked.

‘With my own eyes,’ the bishop said, ‘I witnessed the miracle.’

Alfred was reassured. ‘Tomorrow then,’ he said.

I did not stay to see the power of God unleashed. Instead I took a punt and went south to a place called Æthelingæg which lay at the southern edge of the swamp and was the biggest of all the marsh settlements. I was beginning to learn the swamp. Leofric stayed with Alfred, to protect the king and his family, but I explored, discovering scores of track-ways through the watery void. The paths were called beamwegs and were made of logs that squelched underfoot, but by using them I could walk for miles. There were also rivers that twisted through the low land, and the biggest of those, the Pedredan, flowed close to Æthelingæg which was an island, much of it covered with alders in which deer and wild goats lived, but there was also a large village on the island’s highest spot and the headman had built himself a great hall there. It was not a royal hall, not even as big as the one I had made at Oxton, but a man could stand upright beneath its beams and the island was large enough to accommodate a small army.

A dozen beamwegs led away from Æthelingæg, but none led directly to the mainland. It would be a hard place for Guthrum to attack, because he would have to thread the swamp, but Svein, who we now knew commanded the Danes at Cynuit, at the Pedredan’s mouth, would find it an easy place to approach for he could bring his ships up the river and, just north of Æthelingæg, he could turn south onto the River Thon which flowed past the island. I took the punt into the centre of the Thon and discovered, as I had feared, that it was more than deep enough to float the Dane’s beast-headed ships.

I walked back to the place where the Thon flowed into the Pedredan. Across the wider river was a sudden hill, steep and high, which stood in the surrounding marshland like a giant’s burial mound. It was a perfect place to make a fort, and if a bridge could be built across the Pedredan then no Danish ship could pass up river.

I walked back to the village where I discovered that the headman was a grizzled and stubborn old man called Haswold who was disinclined to help. I said I would pay good silver to have a bridge made across the Pedredan, but Haswold declared the war between Wessex and the Danes did not affect him. ‘There is madness over there,’ he said, waving vaguely at the eastern hills. ‘There’s always madness over there, but here in the swamp we mind our own business. No one minds us and we don’t mind them.’ He stank of fish and smoke. He wore otterskins that were greasy with fish oil and his greying beard was flecked by fish scales. He had small cunning eyes in an old cunning face, and he also had a half-dozen wives, the youngest of whom was a child who could have been his own granddaughter, and he fondled her in front of me as if her existence proved his manhood. ‘I’m happy,’ he said, leering at me, ‘so why should I care for your happiness?’

‘The Danes could end your happiness.’

‘The Danes?’ He laughed at that, and the laugh turned into a cough. He spat. ‘If the Danes come,’ he went on, ‘then we go deep into the swamp and the Danes go.’ He grinned at me and I wanted to kill him, but that would have done no good. There were fifty or more men in the village and I would have lasted all of a dozen heartbeats, though the man I really feared was a tall, broad-shouldered, stooping man with a puzzled look on his face. What frightened me about him was that he carried a long hunting bow. Not one of the short fowling bows that many of the marshmen possessed, but a stag killer, as tall as a man, and capable of shooting an arrow clean through a mail coat. Haswold must have sensed my fear of the bow for he summoned the man to stand beside him. The man looked confused by the summons, but obeyed. Haswold pushed a gnarled hand under the young girl’s clothes then stared at me as he fumbled, laughing at what he perceived as my impotence. ‘The Danes come,’ he said again, ‘and we go deep into the swamp and the Danes go away.’ He thrust his hand deeper into the girl’s goatskin dress and mauled her breasts. ‘Danes can’t follow us, and if they do follow us then Eofer kills them.’ Eofer was the archer and, hearing his name, he looked startled, then worried. ‘Eofer’s my man,’ Haswold boasted, ‘he puts arrows where I tell him to put them.’ Eofer nodded.

‘Your king wants a bridge made,’ I said, ‘a bridge and a fort.’

‘King?’ Haswold stared about the village. ‘I know no king. If any man is king here, ’tis me.’ He cackled with laughter at that and I looked at the villagers and saw nothing but dull faces. None shared Haswold’s amusement. They were not, I thought, happy under his rule and perhaps he sensed what I was thinking for he suddenly became angry, thrusting his girl-bride away. ‘Leave us!’ he shouted at me. ‘Just go away!’

I went away, returning to the smaller island where Alfred sheltered and where Edward lay dying. It was nightfall and the bishop’s prayers to Saint Agnes had failed. Eanflæd told me how Alewold had persuaded Alfred to give up one of his most precious relics, a feather from the dove that Noah had released from the ark. Alewold cut the feather into two parts, returning one part to the king, while the other was scorched on a clean pan and, when it was reduced to ash, the scraps were stirred into a cup of holy water which Ælswith forced her son to drink. He had been wrapped in lambskin, for the lamb was the symbol of Saint Agnes who had been a child martyr in Rome.

But neither feather nor lambskin had worked. If anything, Eanflæd said, the boy was worse. Alewold was praying over him now. ‘He’s given him the last rites,’ Eanflæd said. She looked at me with tears in her eyes. ‘Can Iseult help?’

‘The bishop won’t allow it,’ I said.

‘He won’t allow it?’ she asked indignantly. ‘He’s not the one who’s dying!’

So Iseult was summoned, and Alfred came from the hut and Alewold, scenting heresy, came with him. Edward was coughing again, the sound terrible in the evening silence. Alfred flinched at the noise, then demanded to know if Iseult could cure his son’s illness.

Iseult did not reply at once. Instead she turned and gazed across the swamp to where the moon rose above the mists. ‘The moon gets bigger,’ she said.

‘Do you know a cure?’ Alfred pleaded.

‘A growing moon is good,’ Iseult said dully, then turned on him. ‘But there will be a price.’

‘Whatever you want!’ he said.

‘Not a price for me,’ she said, irritated that he had misunderstood her. ‘But there’s always a price. One lives? Another must die.’

‘Heresy!’ Alewold intervened.

I doubt Alfred understood Iseult’s last three words, or did not care what she meant, he only snatched the tenuous hope that perhaps she could help. ‘Can you cure my son?’ he demanded.

She paused, then nodded. ‘There is a way,’ she said.

‘What way?’

‘My way.’

‘Heresy!’ Alewold warned again.

‘Bishop!’ Eanflæd said warningly, and the bishop looked abashed and fell silent.

‘Now?’ Alfred demanded of Iseult.

‘Tomorrow night,’ Iseult said. ‘It takes time. There are things to do. If he lives till nightfall tomorrow I can help. You must bring him to me at moonrise.’

‘Not tonight?’ Alfred pleaded.

‘Tomorrow,’ Iseult said firmly.

‘Tomorrow is the Feast of Saint Vincent,’ Alfred said, as though that might help, and somehow the child survived that night and, next day, Saint Vincent’s Day, Iseult went with me to the eastern shore where we gathered lichen, burdock, celandine and mistletoe. She would not let me use metal to scrape the lichen or cut the herbs, and before any was collected we had to walk three times around the plants which, because it was winter, were poor and shrivelled things. She also made me cut thorn boughs, and I was allowed to use a knife for that because the thorns were evidently not as important as the lichen or herbs. I watched the skyline as I worked, looking for any Danes, but if they patrolled the edge of the swamp none appeared that day. It was cold, a gusting wind clutching at our clothes. It took a long time to find the plants Iseult needed, but at last her pouch was full and I dragged the thorn bushes back to the island and took them into the hut where she instructed me to dig two holes in the floor. ‘They must be as deep as the child is tall,’ she said, ‘and as far apart from each other as the length of your forearm.’

She would not tell me what the pits were for. She was subdued, very close to tears. She hung the celandine and burdock from a roof beam, then pounded the lichen and the mistletoe into a paste that she moistened with spittle and urine, and she chanted long charms in her own language over the shallow wooden bowl. It all took a long time and sometimes she just sat exhausted in the darkness beyond the hearth and rocked to and fro. ‘I don’t know that I can do it,’ she said once.

‘You can try,’ I said helplessly.

‘And if I fail,’ she said, ‘they will hate me more than ever.’

‘They don’t hate you,’ I said.

‘They think I am a sinner and a pagan,’ she said, ‘and they hate me.’

‘So cure the child,’ I said, ‘and they will love you.’

I could not dig the pits as deep as she wanted, for the soil became ever wetter and, just a couple of feet down, the two holes were filling with brackish water. ‘Make them wider,’ Iseult ordered me, ‘wide enough so the child can crouch in them.’ I did as she said, and then she made me join the two holes by knocking a passage in the damp earth wall that divided them. That had to be done carefully to ensure that an arch of soil remained to leave a tunnel between the holes. ‘It is wrong,’ Iseult said, not talking of my excavation, but of the charm she planned to work. ‘Someone will die, Uhtred. Somewhere a child will die so this one will live.’

‘How do you know that?’ I asked.

‘Because my twin died when I was born,’ she said, ‘and I have his power. But if I use it he reaches from the dark world and takes the power back.’

Darkness fell and the boy went on coughing, though to my ears it sounded feebler now as though there was not enough life left in his small body. Alewold was praying still. Iseult crouched in the door of our hut, staring into the rain, and when Alfred came close she waved him away.

‘He’s dying,’ the king said helplessly.

‘Not yet,’ Iseult said, ‘not yet.’

Edward’s breath rasped. We could all hear it, and we all thought every harsh breath would be his last, and still Iseult did not move, and then at last a rift showed in the rain clouds and a feeble wash of moonlight touched the marsh and she told me to fetch the boy.

Ælswith did not want Edward to go. She wanted him cured, but when I said Iseult insisted on working her charms alone, Ælswith wailed that she did not want her son to die apart from his mother. Her crying upset Edward who began to cough again. Eanflæd stroked his forehead. ‘Can she do it?’ she demanded of me.

‘Yes,’ I said and did not know if I spoke the truth.

Eanflæd took hold of Ælswith’s shoulders. ‘Let the boy go, my lady,’ she said, ‘let him go.’

‘He’ll die!’

‘Let him go,’ Eanflæd said, and Ælswith collapsed into the whore’s arms and I picked up Alfred’s son who felt as light as the feather that had not cured him. He was hot, yet shivering, and I wrapped him in a wool robe and carried him to Iseult.

‘You can’t stay here,’ she told me. ‘Leave him with me.’

I waited with Leofric in the dark. Iseult insisted we could not watch through the hut’s entrance, but I dropped my helmet outside the door and, by crouching under the eaves I could just see a reflection of what happened inside. The small rain died and the moon grew brighter.

The boy coughed. Iseult stripped him naked and rubbed her herb paste on his chest, and then she began to chant in her own tongue, an endless chant it seemed, rhythmic, sad and so monotonous that it almost put me to sleep. Edward cried once, and the crying turned to coughing and his mother screamed from her hut that she wanted him back, and Alfred calmed her and then came to join us and I waved him down so that he would not shadow the moonlight before Iseult’s door.

I peered at the helmet and saw, in the small reflected firelight, that Iseult, naked herself now, was pushing the boy into one of the pits and then, still chanting, she drew him through the earth passage. Her chanting stopped and, instead, she began to pant, then scream, then pant again. She moaned, and Alfred made the sign of the cross, and then there was silence and I could not see properly, but suddenly Iseult cried aloud, a cry of relief, as if a great pain was ended, and I dimly saw her pull the naked boy out of the second pit. She laid him on her bed and he was silent as she crammed the thorn bushes into the tunnel of earth. Then she lay beside the boy and covered herself with my large cloak.

There was silence. I waited, and waited, and still there was silence. And the silence stretched until I understood that Iseult was sleeping, and the boy was sleeping too, or else he was dead, and I picked up the helmet and went to Leofric’s hut. ‘Shall I fetch him?’ Alfred asked nervously.

‘No.’

‘His mother …’ he began.

‘Must wait till morning, lord.’

‘What can I tell her?’

‘That her son is not coughing, lord.’

Ælswith screamed that Edward was dead, but Eanflæd and Alfred calmed her, and we all waited, and still there was silence, and in the end I fell asleep.

I woke in the dawn. It was raining as if the world was about to end, a torrential grey rain that swept in vast curtains from the Sæfern Sea, a rain that drummed on the ground and poured off the reed thatch and made streams on the small island where the little huts crouched. I went to the door of Leofric’s shelter and saw Ælswith watching from her doorway. She looked desperate, like a mother about to hear that her child had died, and there was nothing but silence from Iseult’s hut, and Ælswith began to weep, the terrible tears of a bereaved mother, and then there was a strange sound. At first I could not hear properly, for the seething rain was loud, but then I realised the sound was laughter. A child’s laughter, and a heartbeat later Edward, still naked as an egg, and all muddy from his rebirth through the earth’s passage, ran from Iseult’s hut and went to his mother.

‘Dear God,’ Leofric said.

Iseult, when I found her, was weeping, and would not be consoled. ‘I need you,’ I told her harshly.

She looked up at me. ‘Need me?’

‘To build a bridge.’

She frowned. ‘You think a bridge can be made with spells?’

‘My magic this time,’ I said. ‘I want you healthy. I need a queen.’

She nodded. And Edward, from that day forward, thrived.

The first men came, summoned by the priests I had sent onto the mainland. They came in ones and twos, struggling through the winter weather and the swamp, bringing tales of Danish raids, and when we had two days of sunshine they came in groups of six or seven so that the island became crowded. I sent them out on patrol, but ordered none to go too far west for I did not want to provoke Svein, whose men were camped beside the sea. He had not attacked us yet, which was foolish of him, for he could have brought his ships up the rivers and then struggled through the marsh, but I knew he would attack us when he was ready, and so I needed to make our defences. And for that I needed Æthelingæg.

Alfred was recovering. He was still sick, but he saw God’s favour in his son’s recovery and it never occurred to him that it had been pagan magic that caused the recovery. Even Ælswith was generous and, when I asked her for the loan of her silver fox-fur cloak and what few jewels she possessed, she yielded them without fuss. The fur cloak was dirty, but Eanflæd brushed and combed it.

There were over twenty men on our island now, probably enough to capture Æthelingæg from its sullen headman, but Alfred did not want the marshmen killed. They were his subjects, he said, and if the Danes attacked they might yet fight for us, which meant the large island and its village must be taken by trickery and so, a week after Edward’s rebirth, I took Leofric and Iseult south to Haswold’s settlement. Iseult was dressed in the silver fur and had a silver chain in her hair and a great garnet brooch at her breast. I had brushed her hair till it shone and in that winter’s gloom she looked like a princess come from the bright sky.

Leofric and I, dressed in mail and helmets, did nothing except walk around Æthelingæg, but after a while a man came from Haswold and said the chieftain wished to talk with us. I think Haswold expected us to go to his stinking hut, but I demanded he come to us instead. He could have taken from us whatever he wanted, of course, for there were only the three of us and he had his men, including Eofer the archer, but Haswold had at last understood that dire things were happening in the world beyond the swamp and that those events could pierce even his watery fastness, and so he chose to talk. He came to us at the settlement’s northern gate which was nothing more than a sheep hurdle propped against decaying fish traps and there, as I expected, he gazed at Iseult as though he had never seen a woman before. His small cunning eyes flickered at me and back to her. ‘Who is she?’ he asked.

‘A companion,’ I said carelessly. I turned to look at the sudden steep hill across the river where I wanted the fort made.

‘Is she your wife?’ Haswold asked.

‘A companion,’ I said again. ‘I have a dozen like her,’ I added.

‘I will pay you for her,’ Haswold said. A score of men were behind him, but only Eofer was armed with anything more dangerous than an eel spear.

I turned Iseult to face him, then I stood behind her and put my hands over her shoulders and undid the big garnet brooch. She shivered slightly and I whispered that she was safe and, when the brooch pin slid out of the heavy hide, I pulled her fur cloak apart. I showed her nakedness to Haswold and he dribbled into his fish-scaled beard and his dirty fingers twitched in his foul otterskin furs, and then I closed the cloak and let Iseult fasten the brooch. ‘How much will you pay me?’ I asked him.

‘I can just take her,’ Haswold said, jerking his head at his men.

I smiled at that. ‘You could,’ I said, ‘but many of you will die before we die, and our ghosts will come back to kill your women and make your children scream. Have you not heard that we have a witch with us? You think your weapons can fight magic?’

None of them moved.

‘I have silver,’ Haswold said.

‘I don’t need silver,’ I said. ‘What I want is a bridge and a fort.’ I turned and pointed to the hill across the river. ‘What is that hill called?’

He shrugged. ‘The hill,’ he said, ‘just the hill.’

‘It must become a fort,’ I said, ‘and it must have walls of logs and a gate of logs and a tower so that men can see a long way down river. And then I want a bridge leading to the fort, a bridge strong enough to stop ships.’

‘You want to stop ships?’ Haswold asked. He scratched his groin and shook his head. ‘Can’t build a bridge.’

‘Why not?’

‘Too deep.’ That was probably true. It was low tide now and the Pedredan flowed sullenly between steep and deep mud banks. ‘But I can block the river,’ Haswold went on, his eyes still on Iseult.

‘Block the river,’ I said, ‘and build a fort.’

‘Give her to me,’ Haswold promised, ‘and you will have both.’

‘Do what I want,’ I said, ‘and you can have her, her sisters and her cousins. All twelve of them.’

Haswold would have drained the whole swamp and built a new Jerusalem for the chance to hump Iseult, but he had not thought beyond the end of his prick. But that was far enough for me, and I have never seen work done so quickly. It was done in days. He blocked the river first and did it cleverly by making a floating barrier of logs and felled trees, complete with their tangling branches, all of them lashed together with goathide ropes. A ship’s crew could eventually dismantle such a barrier, but not if they were being assailed by spears and arrows from the fort on the hill that had a wooden palisade, a flooded ditch and a flimsy tower made of alder logs bound together with leather ropes. It was all crude work, but the wall was solid enough, and I began to fear that the small fort would be finished before enough West Saxons arrived to garrison it, but the three priests were doing their job and the soldiers still came, and I put a score of them in Æthelingæg and told them to help finish the fort.

When the work was done, or nearly done, I took Iseult back to Æthelingæg and I dressed her as she had been dressed before, only this time she wore a deerskin tunic beneath the precious fur, and I stood her in the centre of the village and said Haswold could take her. He looked at me warily, then looked at her. ‘She’s mine?’ he asked.

‘All yours,’ I said, and stepped away from her.

‘And her sisters?’ he asked greedily, ‘her cousins?’

‘I shall bring them tomorrow.’

He beckoned Iseult towards his hut. ‘Come,’ he said.

‘In her country,’ I said, ‘it is the custom for the man to lead the woman to his bed.’

He stared at Iseult’s lovely, dark-eyed face above the swathing silver cloak. I stepped further back, abandoning her, and he darted forward, reaching for her, and she brought her hands out from under the thick fur and she was holding Wasp-Sting and its blade sliced up into Haswold’s belly. She gave a cry of horror and surprise as she brought the blade up, and I saw her hesitate, shocked by the effort required to pierce a man’s belly and by the reality of what she had done. Then she gritted her teeth and ripped the blade hard, opening him up like a gutted carp, and he gave a strange mewing cry as he staggered back from her vengeful eyes. His intestines spilled into the mud, and I was beside her then with Serpent-Breath drawn. She was gasping, trembling. She had wanted to do it, but I doubted she would want to do it again.

‘You were asked,’ I snarled at the villagers, ‘to fight for your king.’ Haswold was on the ground, twitching, his blood soaking his otterskin clothes. He made a mewing noise again and one of his filthy hands scrabbled among his own spilt guts. ‘For your king!’ I repeated. ‘When you are asked to fight for your king it is not a request, but a duty! Every man here is a soldier and your enemy is the Danes and if you will not fight them then you will fight against me!’

Iseult still stood beside Haswold who jerked like a dying fish. I edged her away and stabbed Serpent-Breath down to slit his throat. ‘Take his head,’ she told me.

‘His head?’

‘Strong magic.’

We mounted Haswold’s head on the fort wall so that it stared towards the Danes, and in time eight more heads appeared there. They were the heads of Haswold’s chief supporters, murdered by the villagers who were glad to be rid of them. Eofer, the archer, was not one of them. He was a simpleton, incapable of speaking sense, though he grunted and, from time to time, made howling noises. He could be led by a child, but when asked to use his bow he proved to have a terrible strength and uncanny accuracy. He was Æthelingæg’s hunter, capable of dropping a full-grown boar at a hundred paces, and that was what his name meant; boar.

I left Leofric to command the garrison at Æthelingæg and took Iseult back to Alfred’s refuge. She was silent and I thought her sunk in misery, but then she suddenly laughed. ‘Look!’ she pointed at the dead man’s blood matted and sticky in Ælswith’s fur.

She still had Wasp-Sting. That was my short sword, a sax, and it was a wicked blade in a close fight where men are so crammed together that there is no room to swing a long sword or an axe. She trailed the blade in the water, then used the hem of Ælswith’s fur to scrub the diluted blood from the steel. ‘It is harder than I thought,’ she said, ‘to kill a man.’

‘It takes strength.’

‘But I have his soul now.’

‘Is that why you did it?’

‘To give life,’ she said, ‘you must take it from somewhere else.’ She gave me back Wasp-Sting.

Alfred was shaving when we returned. He had been growing a beard, not for a disguise, but because he had been too low in spirits to bother about his appearance, but when Iseult and I reached his refuge he was standing naked to the waist beside a big wooden tub of heated water. His chest was pathetically thin, his belly hollow, but he had washed himself, combed his hair and was now scratching at his stubble with an ancient razor he had borrowed from a marshman. His daughter Æthelflaed was holding a scrap of silver that served as a mirror. ‘I am feeling better,’ he told me solemnly.

‘Good, lord,’ I said, ‘so am I.’

‘Does that mean you’ve killed someone?’

‘She did,’ I jerked my head at Iseult.

He gave her a speculative look. ‘My wife,’ he said, dipping the razor in the water, ‘was asking whether Iseult is truly a queen.’

‘She was,’ I said, ‘but that means little in Cornwalum. She was queen of a dung-heap.’

‘And she’s a pagan?’

‘It was a Christian kingdom,’ I said. ‘Didn’t Brother Asser tell you that?’

‘He said they were not good Christians.’

‘I thought that was for God to judge.’

‘Good, Uhtred, good!’ He waved the razor at me, then stooped to the silver mirror and scraped at his upper lip. ‘Can she foretell the future?’

‘She can.’

He scraped in silence for a few heartbeats. Æthelflaed watched Iseult solemnly. ‘So tell me,’ Alfred said, ‘does she say I will be king in Wessex again?’

‘You will,’ Iseult said tonelessly, surprising me.

Alfred stared at her. ‘My wife,’ he said, ‘says that we can look for a ship now that Edward is better. Look for a ship, go to Frankia and perhaps travel on to Rome. There is a Saxon community in Rome.’ He scraped the blade against his jawbone. ‘They will welcome us.’

‘The Danes will be defeated,’ Iseult said, still tonelessly, but without a quiver of doubt in her voice.

Alfred rubbed his face. ‘The example of Boethius tells me she’s right,’ he said.

‘Boethius?’ I asked, ‘is he one of your warriors?’

‘He was a Roman, Uhtred,’ Alfred said in a tone which chided me for not knowing, ‘and a Christian and a philosopher and a man rich in book-learning. Rich indeed!’ He paused, contemplating the story of Boethius. ‘When the pagan Alaric overran Rome,’ he went on, ‘and all civilisation and true religion seemed doomed, Boethius alone stood against the sinners. He suffered, but he won through, and we can take heart from him. Indeed we can.’ He pointed the razor at me. ‘We must never forget the example of Boethius, Uhtred, never.’

‘I won’t, lord,’ I said, ‘but do you think book-learning will get you out of here?’

‘I think,’ he said, ‘that when the Danes are gone, I shall grow a proper beard. Thank you, my sweet,’ this last was to Æthelflaed. ‘Give the mirror back to Eanflæd, will you?’

Æthelflaed ran off and Alfred looked at me with some amusement. ‘Does it surprise you that my wife and Eanflæd have become friends?’

‘I’m glad of it, lord.’

‘So am I.’

‘But does your wife know Eanflæd’s trade?’ I asked.

‘Not exactly,’ he said. ‘She believes Eanflæd was a cook in a tavern. Which is truth enough. So we have a fort at Æthelingæg?’

‘We do. Leofric commands there and has forty-three men.’

‘And we have twenty-eight here. The very hosts of Midian!’ He was evidently amused. ‘So we shall move there.’

‘Maybe in a week or two.’

‘Why wait?’ he asked.

I shrugged. ‘This place is deeper in the swamp. When we have more men, when we know we can hold Æthelingæg, that is the time for you to go there.’

He pulled on a grubby shirt. ‘Your new fort can’t stop the Danes?’

‘It will slow them, lord. But they could still struggle through the marsh.’ They would find it difficult, though, for Leofric was digging ditches to defend Æthelingæg’s western edge.

‘You’re telling me Æthelingæg is more vulnerable than this place?’

‘Yes, lord.’

‘Which is why I must go there,’ he said. ‘Men can’t say their king skulked in an unreachable place, can they?’ He smiled at me. ‘They must say he defied the Danes. That he waited where they could reach him, that he put himself into danger.’

‘And his family?’ I asked.

‘And his family,’ he said firmly. He thought for a moment. ‘If they come in force they could take all the swamp, isn’t that true?’

‘Yes, lord.’

‘So no place is safer than another. But how large a force does Svein have?’

‘I don’t know, lord.’

‘Don’t know?’ It was a reproof, gentle enough, but still a reproof.

‘I haven’t gone close to them, lord,’ I explained, ‘because till now we’ve been too weak to resist them, and so long as they leave us undisturbed then so long do we leave them undisturbed. There’s no point in kicking a wild bees’ nest, not unless you’re determined to get the honey.’

He nodded acceptance of that argument. ‘But we need to know how many bees there are, don’t we?’ he said. ‘So tomorrow we shall take a look at our enemy. You and me, Uhtred.’

‘No, lord,’ I said firmly. ‘I shall go. You shouldn’t risk yourself.’

‘That is exactly what I need to do,’ he said, ‘and men must know I do it for I am the king, and why would men want a king who does not share their danger?’ He waited for an answer, but I had none. ‘So let’s say our prayers,’ he finished, ‘then we shall eat.’

It was fish stew. It was always fish stew.

And next day we went to find the enemy.

There were six of us. The man who poled the punt, Iseult and I, two of the newly-arrived household troops and Alfred. I tried once again to make him stay behind, but he insisted. ‘If anyone should stay,’ he said, ‘it is Iseult.’

‘She comes,’ I said.

‘Evidently.’ He did not argue, and we all climbed into a large punt and went westwards, and Alfred stared at the birds, thousands of birds. There were coot, moorhen, dabchicks, ducks, grebes and herons, while off to the west, white against the sullen sky, was a cloud of gulls.

The marshman slid us silent and fast through secret channels. There were times when he seemed to be taking us directly into a bank of reeds or grass, yet the shallow craft would slide through into another stretch of open water. The incoming tide rippled through the gaps, bringing fish to the hidden nets and basket traps. Beneath the gulls, far off to the west, I could see the masts of Svein’s fleet, which had been dragged ashore on the coast.

Alfred saw them too. ‘Why don’t they join Guthrum?’

‘Because Svein doesn’t want to take Guthrum’s orders,’ I said.

‘You know that?’

‘He told me so.’

Alfred paused, perhaps thinking of my trial in front of the Witan. He gave me a rueful look. ‘What sort of man is he?’

‘Formidable.’

‘So why hasn’t he attacked us here?’

I had been wondering the same thing. Svein had missed a golden chance to invade the swamp and hunt Alfred down. So why had he not even tried? ‘Because there’s easier plunder elsewhere,’ I suggested, ‘and because he won’t do Guthrum’s bidding. They’re rivals. If Svein takes Guthrum’s orders then he acknowledges Guthrum as his king.’

Alfred stared at the distant masts which showed as small scratches against the sky, then I mutely pointed towards a hill that reared steeply from the western water flats and the marshman obediently went that way, and when the punt grounded we clambered through thick alders and past some sunken hovels where sullen folk in dirty otter fur watched us pass. The marshman knew no name for the place, except to call it Brant, which meant steep, and it was steep. Steep and high, offering a view southwards to where the Pedredan coiled like a great snake through the swamp’s heart. And at the river’s mouth, where sand and mud stretched into the Sæfern Sea, I could see the Danish ships.

They were grounded on the far bank of the Pedredan in the same place that Ubba had grounded his ships before meeting his death in battle. From there Svein could easily row to Æthelingæg, for the river was wide and deep, and he would meet no challenge until he reached the river barrier beside the fort where Leofric waited. I wanted Leofric and his garrison to have some warning if the Danes attacked, and this high hill offered a view of Svein’s camp, but was far enough away so that it would not invite an attack from the enemy. ‘We should make a beacon here,’ I said to Alfred. A fire lit here would give Æthelingæg two or three hours’ warning of a Danish attack.

He nodded, but said nothing. He stared at the distant ships, but they were too far off to count. He looked pale, and I knew he had found the climb to the summit painful, so now I urged him downhill to where the hovels leaked smoke. ‘You should rest here, lord,’ I told him. ‘I’m going to count ships. But you should rest.’

He did not argue and I suspected his stomach pains were troubling him again. I found a hovel that was occupied by a widow and her four children, and I gave her a silver coin and said her king needed warmth and shelter for the day, and I do not think she understood who he was, but she knew the value of a shilling and so Alfred went into her house and sat by the fire. ‘Give him broth,’ I told the widow, whose name was Elwide, ‘and let him sleep.’

She scorned that. ‘Folk can’t sleep while there’s work!’ she said. ‘There are eels to skin, fish to smoke, nets to mend, traps to weave.’

‘They can work,’ I said, pointing to the two household troops, and I left them all to Elwide’s tender mercies while Iseult and I took the punt southwards and, because the Pedredan’s mouth was only three or four miles away, and because Brant was such a clear landmark, I left the marshman to help skin and smoke eels.

We crossed a smaller river and then poled through a long mere broken by marram grass and by now I could see the hill on the Pedredan’s far bank where we had been trapped by Ubba, and I told Iseult the story of the fight as I poled the punt across the shallows. The hull grounded twice and I had to push it into deeper water until I realised the tide was falling fast and so I tied the boat to a rotting stake, then we walked across a drying waste of mud and sea lavender towards the Pedredan. I had grounded farther from the river than I had wanted, and it was a long walk into a cold wind, but we could see all we needed once we reached the steep bank at the river’s edge. The Danes could also see us. I was not in mail, but I did have my swords, and the sight of me brought men to the further shore where they hurled insults across the swirling water. I ignored them. I was counting ships and saw twenty-four beast-headed boats hauled up on the strip of ground where we had defeated Ubba the year before. Ubba’s burned ships were also there, their black ribs half buried in the sand where the men capered and shouted their insults.

‘How many men can you see?’ I asked Iseult.

There were a few Danes in the half wrecked remnants of the monastery where Svein had killed the monks, but most were by the boats. ‘Just men?’ she asked.

‘Forget the women and children,’ I said. There were scores of women, mostly in the small village that was a little way upstream.

She did not know the English words for the bigger numbers, so she gave me her estimate by opening and closing her fingers six times. ‘Sixty?’ I said, and nodded. ‘At most seventy. And there are twenty-four ships.’ She frowned, not understanding the point I made. ‘Twenty-four ships,’ I said, ‘means an army of what? Eight hundred? Nine hundred men? So those sixty or seventy men are the ship-guards. And the others? Where are the others?’ I asked the question of myself, watching as five of the Danes dragged a small boat to the river’s edge. They planned to row across and capture us, but I did not intend to stay that long. ‘The others,’ I answered my own question, ‘have gone south. They’ve left their women behind and gone raiding. They’re burning, killing, getting rich. They’re raping Defnascir.’

‘They’re coming,’ Iseult said, watching the five men clamber into the small boat.

‘You want me to kill them?’

‘You can?’ She looked hopeful.

‘No,’ I said, ‘so let’s go.’

We started back across the long expanse of mud and sand. It looked smooth, but there were runnels cutting through and the tide had turned and the sea was sliding back into the land with surprising speed. The sun was sinking, tangling with black clouds and the wind pushed the flood up the Sæfern and the water gurgled and shivered as it filled the small creeks. I turned to see that the five Danes had abandoned their chase and gone back to the western bank where their fires looked delicate against the evening’s fading light. ‘I can’t see the boat,’ Iseult said.

‘Over there,’ I said, but I was not certain I was right because the light was dimming and our punt was tied against a background of reeds, and now we were jumping from one dry spot to another, and the tide went on rising and the dry spots shrank and then we were splashing through the water and still the wind drove the tide inland.

The tides are big in the Sæfern. A man could make a house at low tide, and by high it would have vanished beneath the waves. Islands appear at low tide, islands with summits thirty feet above the water, and at the high tide they are gone, and this tide was pushed by the wind and it was coming fast and cold and Iseult began to falter so I picked her up and carried her like a child. I was struggling and the sun was behind the low western clouds and it seemed now that I was wading through an endless chill sea, but then, perhaps because the darkness was falling, or perhaps because Hoder, the blind god of the night, favoured me, I saw the punt straining against its tether.

I dropped Iseult into the boat and hauled myself over the low side. I cut the rope, then collapsed, cold and wet and frightened and let the punt drift on the tide.

‘You must get back to the fire,’ Iseult chided me. I wished I had brought the marshman now for I had to find a route across the swamp and it was a long, cold journey in the day’s last light. Iseult crouched beside me and stared far across the waters to where a hill reared up green and steep against the eastern land. ‘Eanflæd told me that hill is Avalon,’ she said reverently.

‘Avalon?’

‘Where Arthur is buried.’

‘I thought you believed he was sleeping?’

‘He does sleep,’ she said fervently. ‘He sleeps in his grave with his warriors.’ She gazed at the distant hill that seemed to glow because it had been caught by the day’s last errant shaft of sunlight spearing from the west beneath the furnace of glowing clouds. ‘Arthur,’ she said in a whisper. ‘He was the greatest king who ever lived. He had a magic sword.’ She told me tales of Arthur, how he had pulled his sword from a stone, and how he had led the greatest warriors to battle, and I thought that his enemies had been us, the English Saxons, yet Avalon was now in England, and I wondered if, in a few years, the Saxons would recall their lost kings and claim they were great and all the while the Danes would rule us. When the sun vanished Iseult was singing softly in her own tongue, but she told me the song was about Arthur and how he had placed a ladder against the moon and netted a swathe of stars to make a cloak for his queen, Guinevere. Her voice carried us across the twilit water, sliding between reeds, and behind us the fires of the Danish ship-guards faded in the encroaching dark and far off a dog howled and the wind sighed cold and a spattering of rain shivered the black mere.

Iseult stopped singing as Brant loomed. ‘There’s going to be a great fight,’ she said softly and her words took me by surprise and I thought she was still thinking of Arthur and imagining that the sleeping king would erupt from his earthy bed in gouts of soil and steel. ‘A fight by a hill,’ she went on, ‘a steep hill, and there will be a white horse and the slope will run with blood and the Danes will run from the Sais.’

The Sais were us, the Saxons. ‘You dreamed this?’ I asked.

‘I dreamed it,’ she said.

‘So it is true?’

‘It is fate,’ she said, and I believed her, and just then the bow of the punt scraped on the island’s shore.

It was pitch dark, but there were fish-smoking fires on the beach, and by their dying light we found our way to Elwide’s house. It was made of alder logs thatched with reeds and I found Alfred sitting by the central hearth where he stared absently into the flames. Elwide, the two soldiers and the marshman were all skinning eels at the hut’s further end where three of the widow’s children were plaiting willow withies into traps and the fourth was gutting a big pike.

I crouched by the fire, wanting its warmth to bring life to my frozen legs.

Alfred blinked as though he was surprised to see me. ‘The Danes?’ he asked.

‘Gone inland,’ I said. ‘Left sixty or seventy men as ship-guards.’ I crouched by the fire, shivering, wondering if I would ever be warm again.

‘There’s food here,’ Alfred said vaguely.

‘Good,’ I said, ‘because we’re starving.’

‘No, I mean there’s food in the marshes,’ he said. ‘Enough food to feed an army. We can raid them, Uhtred, gather men and raid them. But that isn’t enough. I have been thinking. All day, I’ve been thinking.’ He looked better now, less pained, and I suspected he had wanted time to think and had found it in this stinking hovel. ‘I’m not going to run away,’ he said firmly. ‘I’m not going to Frankia.’

‘Good,’ I said, though I was so cold I was not really listening to him.

‘We’re going to stay here,’ he said, ‘raise an army, and take Wessex back.’

‘Good,’ I said again. I could smell burning. The hearth was surrounded by flat stones and Elwide had put a dozen oat bannocks on the stones to cook and the edges nearest the flames were blackening. I moved one of them, but Alfred frowned and gestured for me to stop for fear of distracting him. ‘The problem,’ he said, ‘is that I cannot afford to fight a small war.’

I did not see what other war he could fight, but kept silent.

‘The longer the Danes stay here,’ he said, ‘the firmer their grip. Men will start giving Guthrum their allegiance. I can’t have that.’

‘No, lord.’

‘So they have to be defeated.’ He spoke grimly. ‘Not beaten, Uhtred, but defeated!’

I thought of Iseult’s dream, but said nothing, then I thought how often Alfred had made peace with the Danes instead of fighting them, and still I said nothing.

‘In spring,’ he went on, ‘they’ll have new men and they’ll spread through Wessex until, by summer’s end, there’ll be no Wessex. So we have to do two things.’ He was not so much telling me as just thinking aloud. ‘First,’ he held out one long finger, ‘we have to stop them from dispersing their armies. They have to fight us here. They have to be kept together so they can’t send small bands across the country and take estates.’ That made sense. Right now, from what we heard from the land beyond the swamp, the Danes were raiding all across Wessex, but they were going fast, snatching what plunder they could before other men could take it, but in a few weeks they would start looking for places to live. By keeping their attention on the swamp Alfred hoped to stop that process. ‘And while they look at us,’ he said, ‘the fyrd must be gathered.’

I stared at him. I had supposed he would stay in the swamp until the Danes either overwhelmed us or we gained enough strength to take back a shire, and then another shire, a process of years, but his vision was much grander. He would assemble the army of Wessex under the Danish noses and take everything back at once. It was like a game of dice and he had decided to take everything he had, little as it was, and risk it all on one throw. ‘We shall make them fight a great battle,’ he said grimly, ‘and with God’s help we shall destroy them.’

There was a sudden scream. Alfred, as if startled from a reverie, looked up, but too late, because Elwide was standing over him, screaming that he had burned the oatcakes. ‘I told you to watch them!’ she shouted and, in her fury, she slapped the king with a skinned eel. The blow made a wet sound as it struck and had enough force to knock Alfred sideways. The two soldiers jumped up, hands going to their swords, but I waved them back as Elwide snatched the burned cakes from the stones. ‘I told you to watch them!’ she shrieked, and Alfred lay where he had fallen and I thought he was crying, but then I saw he was laughing. He was helpless with laughter, weeping with laughter, as happy as ever I saw him.

Because he had a plan to take back his kingdom.

Æthelingæg’s garrison now had seventy-three men. Alfred moved there with his family, and sent six of Leofric’s men to Brant armed with axes and orders to make a beacon. He was at his best in those days, calm and confident, the panic and despair of the first weeks of January swept away by his irrational belief that he would regain his kingdom before summer touched the land. He was immensely cheered too by the arrival of Father Beocca who came limping from the landing stage, face beaming, to fall prostrate at the king’s feet. ‘You live, lord!’ Beocca said, clutching the king’s ankles, ‘God be praised, you live!’

Alfred raised him and embraced him, and both men wept and next day, a Sunday, Beocca preached a sermon which I could not help hearing because the service was held in the open air, under a clear cold sky, and Æthelingæg’s island was too small to escape the priest’s voice. Beocca said how David, King of Israel, had been forced to flee his enemies, how he had taken refuge in the cave of Adullam, and how God had led him back into Israel and to the defeat of his enemies. ‘This is our Adullam!’ Beocca said, waving his good hand at Æthelingæg’s thatched roofs, ‘and this is our David!’ he pointed to the king, ‘and God will lead us to victory!’

‘It’s a pity, father,’ I said to Beocca afterwards, ‘that you weren’t this belligerent two months ago.’

‘I rejoice,’ he said loftily, ‘to find you in the king’s good graces.’

‘He’s discovered the value,’ I said, ‘of murderous bastards like me, so perhaps he’ll learn to distrust the advice of snivelling bastards like you who told him the Danes could be defeated by prayer.’

He sniffed at that insult, then looked disapprovingly at Iseult. ‘You have news of your wife?’

‘None.’

Beocca had some news, though none of Mildrith. He had fled south in front of the invading Danes, getting as far as Dornwaraceaster in Thornsæta where he had found refuge with some monks. The Danes had come, but the monks had received warning of their approach and had hidden in an ancient fort that lay near the town. The Danes had sacked Dornwaraceaster, taking silver, coins and women, then they had moved eastwards and shortly after that Huppa, the Ealdorman of Thornsæta, had come to the town with fifty warriors. Huppa had set the monks and townspeople to mending the old Roman walls. ‘The folk there are safe for the moment,’ Beocca told me, ‘but there is not sufficient food if the Danes return and lay siege.’ Then Beocca had heard that Alfred was in the great swamps and Beocca had travelled alone, though on his last day of walking he had met six soldiers going to Alfred and so he had finished his journey with them. He brought no news of Wulfhere, but he had been told that Odda the Younger was somewhere on the upper reaches of the Uisc in an ancient fort built by the old people. Beocca had seen no Danes on his journey. ‘They raid everywhere,’ he said gloomily, ‘but God be praised we saw none of them.’

‘Is Dornwaraceaster a large place?’ I asked.

‘Large enough. It had three fine churches, three!’

‘A market?’

‘Indeed, it was prosperous before the Danes came.’

‘Yet the Danes didn’t stay there?’

‘Nor were they at Gifle,’ he said, ‘and that’s a goodly place.’

Guthrum had surprised Alfred, defeated the forces at Cippanhamm and driven the king into hiding, but to hold Wessex he needed to take all her walled towns, and if Beocca could walk three days across country and see no Danes then it suggested Guthrum did not have the men to hold all he had taken. He could bring more men from Mercia or East Anglia, but then those places might rise against their weakened Danish overlords, so Guthrum had to be hoping that more ships would come from Denmark. In the meantime, we learned, he had garrisons in Baðum, Readingum, Mærlebeorg and Andefera, and doubtless he held other places, and Alfred suspected, rightly as it turned out, that most of eastern Wessex was in Danish hands, but great stretches of the country were still free of the enemy. Guthrum’s men were making raids into those stretches, but they did not have sufficient force to garrison towns like Wintanceaster, Gifle or Dornwaraceaster. In the early summer, Alfred knew, more ships would bring more Danes, so he had to strike before then, to which end, on the day after Beocca arrived, he summoned a council.

There were now enough men on Æthelingæg for a royal formality to prevail. I no longer found Alfred sitting outside a hut in the evening, but instead had to seek an audience with him. On the Monday of the council he gave orders that a large house was to be made into a church, and the family that lived there was evicted and some of the newly-arrived soldiers were ordered to make a great cross for the gable and to carve new windows in the walls. The council itself met in what had been Haswold’s hall, and Alfred had waited till we were assembled before making his entrance, and we had all stood as he came in and waited as he took one of the two chairs on the newly-made dais. Ælswith sat beside him, her pregnant belly swathed in the silver fur cloak that was still stained with Haswold’s blood.

We were not allowed to sit until the Bishop of Exanceaster said a prayer, and that took time, but at last the king waved us down. There were six priests in the half circle and six warriors. I sat beside Leofric, while the other four soldiers were newly-arrived men who had served in Alfred’s household troops. One of those was a grey-bearded man called Egwine who told me he had led a hundred men at Æsc’s Hill and plainly thought he should now lead all the troops gathered in the swamp. I knew he had urged his case with the king and with Beocca who sat just below the dais at a rickety table on which he was trying to record what was said at the council. Beocca was having difficulties for his ink was ancient and faded, his quill kept splitting and his parchments were wide margins torn from a missal, so he was unhappy, but Alfred liked to reduce arguments to writing.

The king formally thanked the bishop for his prayer, then announced, sensibly enough, that we could not hope to deal with Guthrum until Svein was defeated. Svein was the immediate threat for, though most of his men had gone south to raid Defnascir, he still had the ships with which to enter the swamp. ‘Twenty-four ships,’ Alfred said, raising an eyebrow at me.

‘Twenty-four, lord,’ I confirmed.

‘So, when his men are assembled, he can muster near a thousand men.’ Alfred let that figure linger awhile. Beocca frowned as his split quill spattered ink on his tiny patch of parchment.

‘But a few days ago,’ Alfred went on, ‘there were only seventy ship-guards at the mouth of the Pedredan.’

‘Around seventy,’ I said. ‘There could be more we didn’t see.’

‘Fewer than a hundred, though?’

‘I suspect so, lord.’

‘So we must deal with them,’ Alfred said, ‘before the rest return to their ships.’ There was another silence. All of us knew how weak we were. A few men arrived every day, like the half-dozen who had come with Beocca, but they came slowly, either because the news of Alfred’s existence was spreading slowly, or else because the weather was cold and men do not like to travel on wet, cold days. Nor were there any thegns among the newcomers, not one. Thegns were noblemen, men of property, men who could bring scores of well-armed followers to a fight, and every shire had its thegns who ranked just below the reeve and ealdorman, who were themselves thegns. Thegns were the power of Wessex, but none had come to Æthelingæg. Some, we heard, had fled abroad, while others tried to protect their property. Alfred, I was certain, would have felt more comfortable if he had a dozen thegns about him, but instead he had me and Leofric and Egwine. ‘What are our forces now?’ Alfred asked us.

‘We have over a hundred men,’ Egwine said brightly.

‘Of whom only sixty or seventy are fit to fight,’ I said. There had been an outbreak of sickness, men vomiting and shivering and hardly able to control their bowels. Whenever troops gather such sickness seems to strike.

‘Is that enough?’ Alfred asked.

‘Enough for what, lord?’ Egwine was not quick-witted.

‘Enough to get rid of Svein, of course,’ Alfred said, and again there was silence because the question was absurd.

Then Egwine straightened his shoulders. ‘More than enough, lord!’

Ælswith bestowed a smile on him.

‘And how would you propose doing it?’ Alfred asked.

‘Take every man we have, lord,’ Egwine said, ‘every fit man, and attack them. Attack them!’

Beocca was not writing. He knew when he was hearing nonsense and he was not going to waste scarce ink on bad ideas.

Alfred looked at me. ‘Can it be done?’

‘They’ll see us coming,’ I said, ‘they’ll be ready.’

‘March inland,’ Egwine said, ‘come from the hills.’

Again Alfred looked at me. ‘That will leave Æthelingæg undefended,’ I said, ‘and it will take at least three days, at the end of which our men will be cold, hungry and tired, and the Danes will see us coming when we emerge from the hills, and that’ll give them time to put on armour and gather weapons. And at best it will be equal numbers. At worst?’ I just shrugged. After three or four days the rest of Svein’s forces might have returned and our seventy or eighty men would be facing a horde.

‘So how do you do it?’ Alfred asked.

‘We destroy their boats,’ I said.

‘Go on.’

‘Without boats,’ I said, ‘they can’t come up the rivers. Without boats, they’re stranded.’

Alfred nodded. Beocca was scratching away again. ‘So how do you destroy the boats?’ the king asked.

I did not know. We could take seventy men to fight their seventy, but at the end of the fight, even if we won, we would be lucky to have twenty men still standing. Those twenty could burn the boats, of course, but I doubted we would survive that long. There were scores of Danish women at Cynuit and, if it came to a fight, they would join in and the odds were that we would be defeated. ‘Fire,’ Egwine said enthusiastically. ‘Carry fire in punts and throw the fire from the river.’

‘There are ship-guards,’ I said tiredly, ‘and they’ll be throwing spears and axes, sending arrows, and you might burn one boat, but that’s all.’

‘Go at night,’ Egwine said.

‘It’s almost a full moon,’ I said, ‘and they’ll see us coming. And if the moon is clouded we won’t see their fleet.’

‘So how do you do it?’ Alfred demanded again.

‘God will send fire from heaven,’ Bishop Alewold said, and no one responded.

Alfred stood. We all got to our feet. Then he pointed at me. ‘You will destroy Svein’s fleet,’ he said, ‘and I would know how you plan to do it by this evening. If you cannot do it then you,’ he pointed to Egwine, ‘will travel to Defnascir, find Ealdorman Odda and tell him to bring his forces to the river mouth and do the job for us.’

‘Yes, lord,’ Egwine said.

‘By tonight,’ Alfred said to me coldly, and then he walked out.

He left me angry. He had meant to leave me angry. I stalked up to the newly-made fort with Leofric and stared across the marshes to where the clouds heaped above the Sæfern. ‘How are we to burn twenty-four ships?’ I demanded.

‘God will send fire from heaven,’ Leofric said, ‘of course.’

‘I’d rather he sent a thousand troops.’

‘Alfred won’t summon Odda,’ Leofric said. ‘He just said that to annoy you.’

‘But he’s right, isn’t he?’ I said grudgingly. ‘We have to get rid of Svein.’

‘How?’

I stared at the tangled barricade that Haswold had made from felled trees. The water, instead of flowing downstream, was coming upstream because the tide was on the flood and so the ripples ran eastwards from the tangled branches. ‘I remember a story,’ I said, ‘from when I was a small child.’ I paused, trying to recall the tale which, I assume, had been told to me by Beocca. ‘The Christian god divided a sea, isn’t that right?’

‘Moses did,’ Leofric said.

‘And when the enemy followed,’ I said, ‘they were drowned.’

‘Clever,’ Leofric said.

‘So that’s how we’ll do it,’ I said.

‘How?’

But instead of telling him I summoned the marshmen and talked with them, and by that night I had my plan and, because it was taken from the scriptures, Alfred approved it readily. It took another day to get everything ready. We had to gather sufficient punts to carry forty men and I also needed Eofer, the simple-minded archer. He was unhappy, not understanding what I wanted, and he gibbered at us and looked terrified, but then a small girl, perhaps ten or eleven years old, took his hand and explained that he had to go hunting with us. ‘He trusts you?’ I asked the child.

‘He’s my uncle,’ she said. Eofer was holding her hand and he was calm again.

‘Does Eofer do what you tell him?’

She nodded, her small face serious, and I told her she must come with us to keep her uncle happy.

We left before the dawn. We were twenty marshmen, skilled with boats, twenty warriors, a simple-minded archer, a child and Iseult. Alfred, of course, did not want me to take Iseult, but I ignored him and he did not argue. Instead he watched us leave, then went to Æthelingæg’s church that now boasted a newly-made cross of alder-wood nailed to its gable.

And low in the sky above the cross was the full moon. She was low and ghostly pale, and as the sun rose she faded even more, but as the ten punts drifted down the river I stared at her and said a silent prayer to Hoder because the moon is his woman and it was she who must give us victory. Because, for the first time since Guthrum had struck in a winter’s dawn, the Saxons were fighting back.