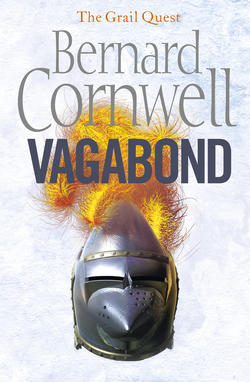

Читать книгу Vagabond - Bernard Cornwell - Страница 9

ОглавлениеA rush of panicked horsemen galloped past the hedge where Thomas, Eleanor and Father Hobbe crouched. Half a dozen horses were riderless while at least a score of others were bleeding from wounds out of which the arrows jutted with their white goose feathers spattered red. The riders were followed by thirty or forty men on foot, some limping, some with arrows stuck in their clothes and a few carrying saddles. They hurried past the burning cottages as a new volley of arrows hastened their retreat, then the thump of hooves made them look back in panic and some of the fugitives broke into a clumsy run as a score of mail-clad horsemen thundered from the mist. Great clods of wet earth spewed up from the horses’ hooves. The stallions were being curbed, forced to take brief steps as their riders took aim at their victims, then the spurs went back as the horses were released to the kill and Eleanor cried aloud in anticipation of the carnage. The heavy swords chopped down. One or two of the fugitives dropped to their knees and held their hands up in surrender, but most tried to escape. One dodged behind a galloping horseman and fled towards the hedge, saw Thomas and his bow and turned straight back into the path of another rider who drove the edge of his heavy sword into the man’s face. The Scotsman went onto his knees, mouth open as though he would scream, but no sound came, only blood seeping between the fingers that were clasped over his nose and eyes. The horseman, who had no shield or helmet, turned his stallion and then leaned out of the saddle to chop his sword into his victim’s neck, killing the man as if he were a cow being pole-axed and that was oddly appropriate because Thomas saw that the mounted killer was wearing the badge of a brown cow on his jupon, which was a short jerkin-like coat half covering his mail hauberk. The jupon was torn, bloodstained and the cow badge had faded so that at first Thomas thought it was a bull. Then the horseman swerved towards Thomas, raised his bloody sword in threat and then noticed the bow and checked his horse. ‘English?’

‘And proud of it!’ Father Hobbe answered for Thomas.

A second horseman, this one with three black ravens embroidered on his white jupon, reined in beside the first. Three prisoners were being pushed towards the two horsemen. ‘How the devil did you get this far in front?’ the newly arrived man asked Thomas.

‘In front?’ Thomas asked.

‘Of the rest of us.’

‘We walked,’ Thomas said, ‘from France. Or at least from London.’

‘From Southampton!’ Father Hobbe corrected Thomas with a pedantry that was utterly out of place on this smoke-stinking hilltop where a Scotsman writhed in his death agonies.

‘France?’ The first man, tangle-haired, brown-faced, and with a northern accent so thick that Thomas found it hard to understand, sounded as if he had never heard of France. ‘You were in France?’ he asked.

‘With the King.’

‘You’re with us now,’ the second man said threateningly, then looked Eleanor up and down. ‘Did you bring the doxie back from France?’

‘Yes,’ Thomas replied curtly.

‘He lies, he lies,’ a new voice said and a third horseman pushed himself forward. He was a lanky man, maybe thirty years old, with a face so red and raw that it looked as though he had scraped his skin off with the bristles when he shaved his sunken cheeks and long jaw. His dark hair was worn long and tied at the nape of his neck with a leather lace. His horse, a scarred roan, was as thin as the rider and had white nervous eyes. ‘I hate goddamn liars,’ the man said, staring at Thomas, then he turned and gave a baleful glance at the prisoners, one of whom wore the red heart badge of the Knight of Liddesdale on his jupon. ‘Almost as much as I hate goddamn Douglases.’

The newcomer wore a padded gambeson in place of a hauberk or haubergeon. It was the kind of protection an archer might wear if he could afford nothing better, yet this man plainly outranked archers for he wore a gold chain about his neck, a mark of distinction reserved for the gentry and above. A battered pig-snouted helmet, as scarred as the horse, hung from his saddle’s pommel, a sword, plainly scabbarded in leather was at his hip, while a shield, painted white with a black axe, hung from his left shoulder. He also had a coiled whip hanging at his belt. ‘The Scots have archers,’ the man said, looking at Thomas, then his unfriendly gaze moved on to Eleanor, ‘and they have women.’

‘I’m English,’ Thomas insisted.

‘We’re all English,’ Father Hobbe said firmly, forgetting that Eleanor was a Norman.

‘A Scotsman would say he was English if it stopped him from being gutted,’ the raw-faced man said caustically. The other two horsemen had fallen back, evidently wary of the thin man who now uncoiled the leather whip and, with a casual skill, flicked it so that the tip snaked out and cracked the air an inch or so from Eleanor’s face. ‘Is she English?’

‘She’s French,’ Thomas said.

The horseman did not answer straightaway, but just stared at Eleanor. The whip rippled as his hand trembled. He saw a fair, slight girl with golden hair and large, frightened eyes. Her pregnancy did not show yet and there was a delicacy to her that spoke of luxury and rare delight. ‘Scot, Welsh, French, what does it matter?’ the man asked. ‘She’s a woman. Do you care where a horse was born before you ride it?’ His own scarred and thin horse became frightened just then because the veering wind blew a sour gust of smoke to its nostrils. It stepped sideways in a series of small, nervous steps until the man drove his spurs back so savagely that he pierced the padded trapper and made the destrier stand shivering in fear. ‘What she is’ – the man spoke to Thomas and pointed his whip handle at Eleanor – ‘don’t matter, but you’re a Scot.’

‘I’m English,’ Thomas said again. A dozen other men wearing the badge of the black axe had come to gaze at Thomas and his companions. The men surrounded the three Scottish prisoners who seemed to know who the horseman with the whip was and did not like the knowledge. More bowmen and men-at-arms watched the cottages burning and laughed at the panicked rats that scrambled from what was left of the collapsed mossy thatch.

Thomas took an arrow from his bag and immediately four or five archers wearing the black-axe livery put arrows on their own strings. The other men in the axe livery grinned expectantly as if they knew this game and enjoyed it, but before it could be played out the horseman was distracted by one of the Scottish prisoners, the man wearing Sir William Douglas’s badge who, taking advantage of his captors’ interest in Thomas and Eleanor, had broken free and run northwards. He had not gone twenty paces before he was ridden down by one of the English men-at-arms and the thin man, amused by the Scotsman’s desperate bid for freedom, pointed at one of the burning cottages. ‘Warm the bastard up,’ he ordered. ‘Dickon! Beggar!’ He spoke to two dismounted men-at-arms. ‘Look after those three.’ He nodded towards Thomas. ‘Watch ’em close!’

Dickon, the younger of the two, was round-faced and grinning, but Beggar was an enormous man, a shambling giant with a face so bearded that his nose and eyes alone could be seen through the tangled, crusted hair beneath the brim of the rusted iron cap that served as a helmet. Thomas was six feet in height, the length of a bow, but he was dwarfed by Beggar whose vast chest strained at a leather jerkin studded with metal plates. At the giant’s waist, suspended by two lengths of rope, were a sword and a morningstar. The sword had no scabbard and its edge was chipped, while one of the spikes on the big metal ball of the morningstar was bent and smeared with blood and hair. The weapon’s three-foot haft banged against the giant’s bare legs as he lurched towards Eleanor. ‘Pretty,’ he said, ‘pretty.’

‘Beggar! Down, boy! Down!’ Dickon ordered cheerfully and Beggar dutifully twitched away from Eleanor, though he still gazed at her and made a low growling noise in his throat. Then a scream made him look towards the nearest burning cottage where the Scotsman, stripped naked now, had been thrust in and out of the fire. The prisoner’s long hair was alight and he frantically beat at the flames as he ran in panicked circles to the amusement of his English captors. Two other Scottish prisoners were squatting nearby, held on the ground by drawn swords.

The thin horseman watched as an archer swathed the prisoner’s hair in a piece of sacking to extinguish the flames. ‘How many of you are there?’ the thin man asked.

‘Thousands!’ the Scotsman answered defiantly.

The horseman leaned on his saddle’s pommel. ‘How many thousands, cully?’

The Scotsman, his beard and hair smoking and his naked skin blackened by embers and lacerated by cuts, did his best to look defiant. ‘More than enough to take you back home in a cage.’

‘He shouldn’t say that to Scarecrow!’ Dickon said, amused. ‘He shouldn’t say that!’

‘Scarecrow?’ Thomas asked. It seemed an appropriate nickname for the horseman with the black-axe badge was lean, poor and frightening.

‘He be Sir Geoffrey Carr to you, cully,’ Dickon said, watching the Scarecrow admiringly.

‘And who is Sir Geoffrey Carr?’ Thomas asked.

‘He be Scarecrow and he be Lord of Lackby,’ Dickon said in a tone which suggested everyone knew who Sir Geoffrey Carr was, ‘and he be having his Scarecrow games now!’ Dickon grinned because Sir Geoffrey, the whip coiled at his waist again, had dropped down from his horse and with a drawn knife, approached the Scottish prisoner.

‘Hold him down,’ Sir Geoffrey ordered the archers, ‘hold him down and spread his legs.’

‘Non!’ Eleanor cried in protest.

‘Pretty,’ Beggar said in his voice that rumbled deep inside his huge chest.

The Scotsman screamed and tried to pull himself away, but he was tripped, then held down by three archers while the man evidently known throughout the north as the Scarecrow knelt between his legs. Somewhere in the clearing fog a raven cawed. A handful of archers was staring north in case the Scots returned, but most were watching the Scarecrow and his knife. ‘You want to keep your shrivelled collops?’ Sir Geoffrey asked the Scotsman. ‘Then tell me how many there are of you.’

‘Fifteen thousand? Sixteen?’ The Scotsman was suddenly eager to talk.

‘He means ten or eleven thousand,’ Sir Geoffrey announced to the listening archers, ‘which is more than enough for our few arrows. And is your bastard King here?’

The Scotsman bridled at that, but a touch of the knife blade to his groin reminded him of his predicament. ‘David Bruce is here, aye.’

‘Who else?’

The desperate Scotsman named his army’s other leaders. The King’s nephew and heir to his throne, Lord Robert Stewart, was with the invading army, as were the Earls of Moray, of March, of Wigtown, Fife and Menteith. He named others, clan chiefs and wild men from the wastelands of the far north, but Carr was more interested in two of the earls. ‘Fife and Menteith?’ he asked. ‘They’re here?’

‘Aye, sir, they are.’

‘But they swore fealty to King Edward,’ Sir Geoffrey said, evidently disbelieving the man.

‘They march with us now,’ the Scotsman insisted, ‘as does Douglas of Liddesdale.’

‘That ripe bastard,’ Sir Geoffrey said, ‘that shit of hell.’ He stared northwards through the fog shredding from the ridge, which was being revealed as a narrow and rocky plateau running north and south. The pasture on the plateau was thin and the ridge’s weathered stone protruded through the grass like the ribs of a starving man. Off to the north-east, beyond the valley of mist, the cathedral and castle of Durham reared up on their river-lapped crag, while to the west were hills and woods and stone-walled fields cut with small streams. Two buzzards sailed above the ridge, going towards the Scottish army that was still concealed by the fog which lingered to the north, but Thomas was thinking that it would not be long before troops came to find the men who had run their fellow Scots away from the crossroads.

Sir Geoffrey leaned back and went to return his knife to its scabbard, then seemed to remember something and grinned at the prisoner. ‘You were going to take me back to Scotland in a cage, is that right?’

‘No!’

‘But you were! And why would I want to see Scotland? I can peer down a jakes whenever I want.’ He spat at the prisoner then nodded at the archers. ‘Hold him.’

‘No!’ the Scotsman shouted, then the shout turned to a terrible scream as Sir Geoffrey leaned forward with the knife again. The prisoner twitched and heaved as the Scarecrow, the front of his padded gambeson now sheeted with blood, stood up. The prisoner was still screaming, hands clutched to his bloody groin, and the sight brought a smile to the Scarecrow’s lips. ‘Throw the rest of him into the fire,’ he said, then turned to look at the other two Scottish prisoners. ‘Who is your master?’ he demanded of them.

They hesitated, then one licked his lips. ‘We serve Douglas,’ he said proudly.

‘I hate Douglas. I hate every Douglas that ever dropped out of the devil’s backside.’ Sir Geoffrey shuddered, then turned to his horse. ‘Burn them both,’ he ordered.

Thomas, looking away from the sudden blood, had seen a stone cross fallen at the crossroad’s centre. He stared at it, not seeing the carved dragon, but hearing the echoes of the noise and then the new screams as the prisoners were hurled into the flames. Eleanor ran to him and held his arm tight.

‘Pretty,’ Beggar said.

‘Here, Beggar, here!’ Sir Geoffrey called. ‘Hoist me!’ The giant made a step with his hands and Sir Geoffrey used it to climb into his saddle, then he kicked the horse towards Thomas and Eleanor. ‘I’m always hungry,’ Sir Geoffrey said, ‘after a gelding.’ He turned to watch the fire where one of the Scotsmen, hair flaming, tried to escape, but was prodded back into the inferno by a dozen bowstaves. The man’s howl was abruptly cut short as he collapsed. ‘I’m in the mood to geld and burn Scotsmen today,’ Sir Geoffrey said, ‘and you look like a Scot to me, boy.’

‘I’m not a boy,’ Thomas said, the anger rising in him.

‘You look like a bloody boy to me, boy. A Scots boy, maybe?’ Sir Geoffrey, plainly amused by Thomas’s temper, grinned at his newest victim who did indeed look young, though Thomas was twenty-two summers old and had fought for the last four of them in Brittany, Normandy and Picardy. ‘You look Scots, boy,’ the Scarecrow said, daring Thomas to defy him again. ‘All the Scots are black!’ he appealed to the crowd to judge Thomas’s complexion, and it was true that Thomas had a sun-darkened skin and black hair, but so did a score or more of the Scarecrow’s own archers. And though Thomas looked young he also looked hard. His hair was cropped close to his skull and four years of war had hollowed his cheeks, but there was still something distinctive in his looks, a handsomeness that attracted the eye and served to spur Sir Geoffrey Carr’s jealousy. ‘What’s on your horse?’ Sir Geoffrey jerked his head towards Thomas’s mare.

‘Nothing of yours,’ Thomas said.

‘What’s mine is mine, boy, and what’s yours is mine if I want it. Mine to take or mine to give. Beggar! You want that girl?’

Beggar grinned behind his beard and jerked his head up and down. ‘Pretty,’ he said. He scratched at the lice in his beard. ‘Beggar likes pretty.’

‘I reckon you can have the pretty when I’m through with her,’ Sir Geoffrey said with a grin and he took the whip from where it hung at his waist and cracked it in the air. Thomas saw that the long leather thong had a small iron claw at its end. Sir Geoffrey grinned at Thomas again, then drew back the whip as a threat. ‘Strip her, Beggar,’ he said, ‘let’s give the boys a bit of pleasure,’ and he was still grinning as Thomas swung his heavy bowstave hard into the teeth of Sir Geoffrey’s horse and the animal reared up, screaming, as Thomas knew it would, and the Scarecrow, unready for the motion, fell backwards, flailing for balance, and his men, who should have protected him, were so intent on the burning Scottish prisoners that not one drew a bow or a blade before Thomas had dragged Sir Geoffrey down from the saddle and had him on the ground with a knife at his throat.

‘I’ve been killing men for four years,’ Thomas said, ‘and not all of them were Frenchmen.’

‘Thomas!’ Eleanor screamed.

‘Take her, Beggar! Take her!’ Sir Geoffrey shouted. He heaved up, but Thomas was an archer and years of drawing his big black bow had given him extraordinary strength in the arms and chest and Sir Geoffrey could not budge him, so he spat at Thomas instead. ‘Take her, Beggar!’ he yelled again.

The Scarecrow’s men ran towards their master, but checked when they saw that Thomas had a knife at his captive’s throat.

‘Strip her, Beggar! Strip the pretty! We’ll all have her!’ Sir Geoffrey bawled, apparently oblivious of the blade at his gullet.

‘Who reads here? Who reads?’ Father Hobbe bellowed. The odd question checked everyone, even Beggar who had already snatched off Eleanor’s hat and now had his huge left arm around her neck while his right hand gripped the neckline of her frock. ‘Who in this company can read?’ Father Hobbe demanded again as he brandished the parchment he had taken from one of the sacks on the back of Thomas’s horse. ‘This is a letter from my lord the Bishop of Durham who is with our lord the King in France and it is sent to John Fossor, Prior of Durham, and only Englishmen who have fought with our King would carry such a letter. We have brought it from France.’

‘It proves nothing!’ Sir Geoffrey shouted, then spat at Thomas again as the blade was pressed hard into his throat.

‘And in what language is this letter written?’ A new horseman had spurred through the Scarecrow’s men. He wore no surcoat or jupon, but the badge on his battered shield was a scallop shell on a cross and it proclaimed that he was not one of Sir Geoffrey’s followers. ‘What language?’ he asked once more.

‘Latin,’ Thomas said, his knife still pressing hard into Sir Geoffrey’s neck.

‘Let Sir Geoffrey up,’ the newcomer commanded Thomas, ‘and I shall read the letter.’

‘Tell him to let my woman go,’ Thomas snarled.

The horseman looked surprised at being given an order by a mere archer, but he did not protest. Instead he urged his horse towards Beggar. ‘Let her go,’ he said and, when the big man did not obey, he half drew his sword. ‘You want me to crop your ears, Beggar? Is that it? Two ears gone? Then your nose, then your cock, is that what you want, Beggar? You want to be shorn like a summer ewe? Trimmed down like an elf?’

‘Let her go, Beggar,’ Sir Geoffrey said sullenly.

Beggar obeyed and stepped back and the horseman leaned down from his saddle to take the letter from Father Hobbe. ‘Let Sir Geoffrey go,’ the newcomer ordered Thomas, ‘for we shall have peace between Englishmen today, at least for a day.’

The horseman was an old man, at least fifty years old, with a great shock of white hair that looked as though it had never been close to a brush or comb. He was a large man, tall and big-bellied, on a sturdy horse that had no trapper, but only a tattered saddle cloth. The man’s full-length mail coat was sadly rusted in places and torn in others, while over the coat he had a breastplate that had lost two of its straps. A long sword hung at his right thigh. He looked to Thomas like a yeoman farmer who had ridden to war with whatever equipment his neighbours could lend him, but he had been recognized by Sir Geoffrey’s archers who had snatched off their hats and helmets when he appeared and who now treated him with deference. Even Sir Geoffrey seemed cowed by the white-haired man who frowned as he read the letter. ‘Thesaurus, eh?’ He was speaking to himself. ‘And a fine kettle of fish that is! A thesaurus indeed!’ Thesaurus was Latin, but the rest of his words were spoken in Norman French and he was evidently confident that no archer would understand him.

‘Mention of treasure’ – Thomas used the same language, which had been taught to him by his father – ‘makes men excited. Over-excited.’

‘Good Lord above, good Lord indeed, you speak French! Miracles never cease. Thesaurus, it does mean treasure, doesn’t it? My Latin is not what it was when I was young. I had it flogged into me by a priest and it seems to have mostly leaked out since. A treasure, eh? And you speak French!’ The horseman showed genial surprise that Thomas spoke the language of aristocrats, though Sir Geoffrey, who did not speak French, looked alarmed for it suggested Thomas might be a good deal better born than he had thought. The horseman gave the letter back to Father Hobbe, then spurred to Sir Geoffrey. ‘You were picking a squabble with an Englishman, Sir Geoffrey, a messenger, no less, from our lord the King. How do you explain that?’

‘I don’t have to explain anything,’ Sir Geoffrey said, ‘my lord.’ The last two words were added reluctantly.

‘I should fillet you now,’ his lordship said mildly, ‘then have you stuffed and mounted on a pole to scare the crows away from my newly born lambs. I could show you at Skipton Fair, Sir Geoffrey, as an example to other sinners.’ He seemed to consider that idea for a few heartbeats, then shook his head. ‘Just get on your horse,’ he said, ‘and fight the Scots today instead of quarrelling with your fellow Englishman.’ He turned in his saddle and raised his voice so all the archers and men-at-arms could hear him. ‘All of you, back down the ridge! And quick, before the Scots come and drive you off! You want to join those rascals in the fire?’ He pointed to the three Scottish prisoners who were now nothing but dark shrivelled shapes in the bright flames, then he beckoned Thomas and changed his language to French. ‘You’ve really come from France?’

‘Yes, my lord.’

‘Then do me the courtesy, my dear fellow, of speaking with me.’

They went south, leaving a broken stone cross, burned men and arrow-struck corpses in a thinning mist, where the army of Scotland had come to Durham.

Bernard de Taillebourg took the crucifix from about his neck and kissed the writhing figure of Christ that was pinned to the small wooden cross. ‘God be with you, my brother,’ he murmured to the old man lying on the stone bench cushioned by a palliasse of straw and a folded blanket. A second blanket, just as thin, covered the old man whose hair was white and wispy.

‘It is cold,’ Brother Hugh Collimore said feebly, ‘so cold.’ He spoke in French, though to de Taillebourg the old monk’s accent was barbarous for it was the French of Normandy and of England’s Norman rulers.

‘Winter comes,’ de Taillebourg said. ‘You can smell it on the wind.’

‘I am dying’ – Brother Collimore turned his red-rimmed eyes on his visitor – ‘and can smell nothing. Who are you?’

‘Take this,’ de Taillebourg said and gave his crucifix to the old monk, then he stoked up the wood fire, put two more logs on the revived blaze and sniffed a jug of mulled wine that sat in the hearth. It was not too rank and so he poured some into a horn cup. ‘At least you have a fire,’ he said, stooping to peer through the small window, no bigger than an arrow slit, that faced west across the encircling Wear. The monks’ hospital was on the slope of Durham’s hill, beneath the cathedral, and de Taillebourg could see the Scottish men-at-arms carrying their lances through the straggling remnants of mist on the skyline. Few of the mail-clad men had horses, he noticed, suggesting that the Scots planned to fight on foot.

Brother Collimore, his face pale and his voice frail, gripped the small cross. ‘The dying are allowed a fire,’ he said, as though he had been accused of indulging himself in luxury. ‘Who are you?’

‘I come from Cardinal Bessières,’ de Taillebourg said, ‘in Paris, and he sends you his greetings. Drink this, it will warm you.’ He held the mulled wine towards the old man.

Collimore refused the wine. His eyes were cautious. ‘Cardinal Bessières?’ he asked, his tone implying that the name was new to him.

‘The Pope’s legate in France.’ De Taillebourg was surprised that the monk did not recognize the name, but thought perhaps the dying man’s ignorance would be useful. ‘And the Cardinal is a man,’ the Dominican went on, ‘who loves the Church as fiercely as he loves God.’

‘If he loves the Church,’ Collimore said with a surprising force, ‘then he will use his influence to persuade the Holy Father to take the papacy back to Rome.’ The statement exhausted him and he closed his eyes. He had never been a big man, but now, beneath his lice-ridden blanket, he seemed to have shrunk to the size of a ten-year-old and his white hair was thin and fine like a small infant’s. ‘Let him move the papacy to Rome,’ he said again, though feebly, ‘for all our troubles have worsened since it was moved to Avignon.’

‘Cardinal Bessières wants nothing more than to move the Holy Father back to Rome,’ de Taillebourg lied, ‘and perhaps you, brother, can help us achieve that.’

Brother Collimore appeared not to hear the words. He had opened his eyes again, but just lay gazing up at the whitewashed stones of the arched ceiling. The room was low, chill and white. Sometimes, when the summer sun was high, he could see the flicker of reflected water on the white stones. In heaven, he thought, he would be forever within sight of crystal rivers and under a warm sun. ‘I was in Rome once,’ he said wistfully. ‘I remember going down some steps into a church where a choir sang. So beautiful.’

‘The Cardinal wants your help,’ de Taillebourg said.

‘There was a saint there.’ Collimore was frowning, trying to remember. ‘Her bones were yellow.’

‘So the Cardinal sent me to see you, brother,’ de Taillebourg said softly. His servant, dark-eyed and elegant, watched from the door.

‘Cardinal Bessières,’ Brother Collimore said in a whisper.

‘He sends you his greetings in Christ, brother.’

‘What Bessières wants,’ Collimore said, still in a whisper, ‘he takes with whips and scorpions.’

De Taillebourg half smiled. So Collimore did know of Cardinal Bessières after all, and no wonder, but perhaps fear of Bessières would be sufficient to elicit the truth. The monk had closed his eyes again and his lips were moving silently, suggesting he was praying. De Taillebourg did not disturb the prayers, but just gazed through the small window to where the Scots were making their battleline on the far hill. The invaders faced southwards so that the left end of their line was nearest to the city and de Taillebourg could see men jostling for position as they tried to take the places of honour closest to their lords. The Scots had evidently decided to fight on foot so that the English archers could not destroy their men-at-arms by cutting down their horses. There was no sign of those English yet, though from all de Taillebourg had heard they could not have assembled a great force. Their army was in France, outside Calais, not here, so perhaps it was merely a local lord leading his retainers? Yet plainly there were enough men to persuade the Scots to form a battleline, and de Taillebourg did not expect David’s army to be delayed for long. Which meant that if he wanted to hear the old man’s story and be away from Durham before the Scots entered the city then he had best make haste. He looked back at the monk, ‘Cardinal Bessières wants only the glory of the Church and of God. And he wants to know about Father Ralph Vexille.’

‘Dear God,’ Collimore said, and his fingers traced the bone figure on the small crucifix as he opened his eyes and turned his head to stare at the priest. The monk’s expression suggested it was the first time he had really noticed de Taillebourg and he shuddered, recognizing in his visitor a man who believed suffering gave merit. A man, Collimore reflected, who would be as implacable as his master in Paris. ‘Vexille!’ Collimore said, as though he had almost forgotten the name, and then he sighed. ‘It is a long tale,’ he said tiredly.

‘Then I will tell you what I know of it,’ de Taillebourg said. The gaunt Dominican was pacing the room now, turning and turning again in the small space under the highest part of the arched ceiling. ‘You have heard,’ he demanded, ‘that a battle was fought in Picardy in the summer? Edward of England fought his cousin of France and a man came from the south to fight for France and on his banner was the device of a yale holding a cup.’ Collimore blinked, but said nothing. His eyes were fixed on de Taillebourg who, in turn, stopped his pacing to look at the priest. ‘A yale holding a cup,’ he repeated.

‘I know the beast,’ Collimore said sadly. A yale was an heraldic animal, unknown in nature, clawed like a lion, horned like a goat and scaled like a dragon.

‘He came from the south,’ de Taillebourg said, ‘and he thought that by fighting for France he would wash from his family’s crest the ancient stains of heresy and of treason.’ Brother Collimore was far too sick to see that the priest’s servant was now listening intently, almost fiercely, or to notice that the Dominican had raised his voice slightly to make it easier for the servant, who still stood in the doorway, to overhear. ‘This man came from the south, riding in pride, believing his soul to be beyond reproof, but no man is beyond God’s reach. He thought he would ride in victory into the King’s affections, but instead he shared France’s defeat. God will sometimes humble us, brother, before raising us to glory.’ De Taillebourg spoke to the old monk, but his words were for his servant’s ears. ‘And after the battle, brother, when France wept, I found this man and he talked of you.’

Brother Collimore looked startled, but said nothing.

‘He talked of you,’ Father de Taillebourg said, ‘to me. And I am an Inquisitor.’

Brother Collimore’s fingers fluttered in an attempt to make the sign of the cross. ‘The Inquisition,’ he said feebly, ‘has no authority in England.’

‘The Inquisition has authority in heaven and in hell, and you think little England can stand against us?’ The fury in de Taillebourg’s voice echoed in the hospital cell. ‘To root out heresy, brother, we will ride to the ends of the earth.’

The Inquisition, like the Dominican order of friars, was dedicated to the eradication of heresy, and to do it they employed fire and pain. They could not shed blood, for that was against the law of the Church, but any pain inflicted without blood-letting was permitted, and the Inquisition knew well that fire cauterized bleeding and that the rack did not pierce a heretic’s skin and that great weights pressed on a man’s chest burst no veins. In cellars reeking of fire, fear, urine and smoke, in a darkness shot through with flamelight and the screams of heretics, the Inquisition hunted down the enemies of God and, by the application of bloodless pain, brought their souls into a blessed unity with Christ.

‘A man came from the south,’ de Taillebourg said to Collimore again, ‘and the crest on his shield was a yale holding a cup.’

‘A Vexille,’ Collimore said.

‘A Vexille,’ de Taillebourg said, ‘who knew your name. Now why, brother, would a heretic from the southern lands know the name of an English monk in Durham?’

Brother Collimore sighed. ‘They all knew,’ he said tiredly, ‘the whole family knew. They knew because Ralph Vexille was sent to me. The bishop thought I could cure him of madness, but his family feared he would tell me secrets instead. They wanted him dead, but we locked him away in a cell where no one but I could reach him.’

‘And what secrets did he tell you?’ de Taillebourg asked.

‘Madness,’ Brother Collimore said, ‘just madness.’ The servant stood in the doorway and watched him.

‘Tell me of the madness,’ the Dominican ordered.

‘The mad speak of a thousand things,’ Brother Collimore said, ‘they speak of spirits and phantoms, of snow in summer and darkness in the daylight.’

‘But Father Ralph spoke to you of the Grail,’ de Taillebourg said flatly.

‘He spoke of the Grail,’ Brother Collimore confirmed.

The Dominican let out a sigh of relief. ‘What did he tell you of the Grail?’

Hugh Collimore said nothing for a while. His chest rose and fell so feebly that the motion was scarcely visible, then he shook his head. ‘He told me that his family had owned the Grail and that he had stolen and hidden it! But he spoke of a hundred such things. A hundred such things.’

‘Where would he have hidden it?’ de Taillebourg enquired.

‘He was mad. Mad. It was my job, you know, to look after the mad? We starved or beat them to drive the devils out, but it did not always work. In winter we would plunge them into the river, through the ice, and that worked. Devils hate the cold. It worked with Ralph Vexille, or mostly it worked. We released him after a while. The demons were gone, you see.’

‘Where did he hide the Grail?’ De Taillebourg’s voice was harder and louder.

Brother Collimore stared at the flicker of reflected water light on the ceiling. ‘He was mad,’ he whispered, ‘but he was harmless. Harmless. And when he left here he was sent to a parish in the south. In the far south.’

‘At Hookton in Dorset?’

‘At Hookton in Dorset,’ Brother Collimore agreed, ‘where he had a son. He was a great sinner, you see, even though he was a priest. He had a son.’

Father de Taillebourg stared at the monk who had, at last, given him some news. A son? ‘What do you know of the son?’

‘Nothing.’ Brother Collimore sounded surprised that he should be asked.

‘And what do you know of the Grail?’ de Taillebourg probed.

‘I know that Ralph Vexille was mad,’ Collimore said in a whisper.

De Taillebourg sat on the hard bed. ‘How mad?’

Collimore’s voice became even softer. ‘He said that even if you found the Grail then you would not know it, not unless you were worthy.’ He paused and a look of puzzlement, almost amazement, showed briefly on his face. ‘You had to be worthy, he said, to know what the Grail was, but if you were worthy then it would shine like the very sun. It would dazzle you.’

De Taillebourg leaned close to the monk. ‘You believed him?’

‘I believe Ralph Vexille was mad,’ Brother Collimore said.

‘The mad sometimes speak truth,’ de Taillebourg said.

‘I think,’ Brother Collimore went on as though the Inquisitor had not spoken, ‘that God gave Ralph Vexille a burden too great for him to bear.’

‘The Grail?’ de Taillebourg asked.

‘Could you bear it? I could not.’

‘So where is it?’ de Taillebourg persisted. ‘Where is it?’

Brother Collimore looked puzzled again. ‘How would I know?’

‘It was not at Hookton,’ de Taillebourg said, ‘Guy Vexille searched for it.’

‘Guy Vexille?’ Brother Collimore asked.

‘The man who came from the south, brother, to fight for France and ended in my custody.’

‘Poor man,’ the monk said.

Father de Taillebourg shook his head. ‘I merely showed him the rack, let him feel the pincers and smell the smoke. Then I offered him life and he told me all he knew and he told me the Grail was not at Hookton.’

The old monk’s face twitched in a smile. ‘You did not hear me, father. If a man is unworthy then the Grail would not reveal itself. Guy Vexille could not have been worthy.’

‘But Father Ralph did possess it?’ De Taillebourg sought reassurance. ‘You think he really possessed it?’

‘I did not say as much,’ the monk said.

‘But you believe he did?’ de Taillebourg asked and, when Brother Collimore said nothing, he nodded to himself. ‘You do believe he did.’ He slipped off the bed, going to his knees and a look of awe came to his face as his linked hands clawed at each other. ‘The Grail,’ he said in a tone of utter wonder.

‘He was mad,’ Brother Collimore warned him.

De Taillebourg was not listening. ‘The Grail,’ he said again, ‘le Graal!’ He was clutching himself now, rocking back and forth in ecstasy. ‘Le Graal!’

‘The mad say things,’ Brother Collimore said, ‘and they do not know what they say.’

‘Or God speaks through them,’ de Taillebourg said fiercely.

‘Then God sometimes has a terrible tongue,’ the old monk replied.

‘You must tell me,’ de Taillebourg insisted, ‘all that Father Ralph told you.’

‘But it was so long ago!’

‘It is le Graal!’ de Taillebourg shouted and, in his frustration, he shook the old man. ‘It is le Graal! Don’t tell me you have forgotten.’ He glanced through the window and saw, raised on the far ridge, the red saltire on the yellow banner of the Scottish King and beneath it a mass of grey-mailed men with their thicket of lances, pikes and spears. No English foe was in sight, but de Taillebourg would not have cared if all the armies of Christendom were come to Durham for he had found his vision, it was the Grail, and though the world should tremble with armies all about him, he would pursue it.

And an old monk talked.

The horseman with the rusted mail, broken-strapped breastplate and scallop-decorated shield named himself as Lord Outhwaite of Witcar. ‘Do you know the place?’ he asked Thomas.

‘Witcar, my lord? I’ve not heard of it.’

‘Not heard of Witcar! Dear me. And it’s such a pleasant place, very pleasant. Good soil, sweet water, fine hunting. Ah, there you are!’ This last was to a small boy mounted on a large horse and leading a second destrier by the reins. The boy wore a jupon that had the scalloped cross emblazoned in yellow and red and, tugging the warhorse behind him, he spurred towards his master.

‘Sorry, my lord,’ the boy said, ‘but Hereward do haul away, he do.’ Hereward was evidently the destrier he led. ‘And he hauled me clean away from you!’

‘Give him to this young man here,’ Lord Outhwaite said. ‘You can ride?’ he added earnestly to Thomas.

‘Yes, my lord.’

‘Hereward is a handful though, a rare handful. Kick him hard to let him know who’s master.’

A score of men appeared in Lord Outhwaite’s livery, all mounted and all with armour in better repair than their master’s. Lord Outhwaite turned them back south. ‘We were marching on Durham,’ he told Thomas, ‘just minding our own affairs as good Christians should, and the wretched Scots appeared! We won’t make Durham now. I was married there, you know? In the cathedral. Thirty-two years ago, can you credit it?’ He beamed happily at Thomas. ‘And my dear Margaret still lives, God be praised. She’d like to hear your tale. You really were at Wadicourt?’

‘I was, my lord.’

‘Fortunate you, fortunate you!’ Lord Outhwaite said, then hailed yet more of his men to turn them about before they blundered into the Scots. Thomas was rapidly coming to realize that Lord Outhwaite, despite his ragged mail and dishevelled appearance, was a great lord, one of the magnates of the north country, and his lordship confirmed this opinion by grumbling that he had been forbidden by the King to fight in France because he and his men might be needed to fend off an invasion by the Scots. ‘And he was quite right!’ Lord Outhwaite sounded surprised. ‘The wretches have come south! Did I tell you my eldest boy was in Picardy? That’s why I’m wearing this.’ He plucked at a rent in the old mail coat. ‘I gave him the best armour we had because I thought we wouldn’t need it here! Young David of Scotland always seemed peaceable enough to me, but now England’s overrun by his fellows. Is it true that the slaughter at Wadicourt was vast?’

‘It was a field of dead, my lord.’

‘Theirs, not ours, God and His saints be thanked.’ His lordship looked across at some archers straggling southwards. ‘Don’t dawdle!’ he called in English. ‘The Scots will be looking for you soon enough.’ He looked back to Thomas and grinned. ‘So what would you have done if I hadn’t come along?’ he asked, still using English. ‘Cut the Scarecrow’s throat?’

‘If I had to.’

‘And had your own slit by his men,’ Lord Outhwaite observed cheerfully. ‘He’s a poisonous tosspot. God only knows why his mother didn’t drown him at birth, but then she was a goddamned turd-hearted witch if ever there was one.’ Like many lords who had grown up speaking French, Lord Outhwaite had learned his English from his parents’ servants and so spoke it coarsely. ‘He deserves a slit throat, the Scarecrow does, but he’s a bad enemy to have. He holds a grudge better than any man alive, but he has so many grudges that maybe he don’t have room for one more. He hates Sir William Douglas most of all.’

‘Why?’

‘Because Willie had him prisoner. Mind you, Willie Douglas has held most of us prisoner at one time or another and one or two of us have even held him in return, but the ransom near killed Sir Geoffrey. He’s down to his last score of retainers and I’d be surprised if he’s got more than three halfpennies in a pot. The Scarecrow’s a poor man, very poor, but he’s proud, and that makes him a bad enemy to have.’ Lord Outhwaite paused to raise a genial hand to a group of archers wearing his livery. ‘Wonderful fellows, wonderful. So tell me about the battle at Wadicourt. Is it true that the French rode down their own archers?’

‘They did, my lord. Genoese crossbowmen.’

‘So tell me all that happened.’

Lord Outhwaite had received a letter from his eldest son that told of the battle in Picardy, but he was desperate to hear of the fight from someone who had stood on that long green slope between the villages of Wadicourt and Crécy, and Thomas now told how the enemy had attacked late in the afternoon and how the arrows had flown down the hill to cut the King of France’s great army into heaps of screaming men and horses, and how some of the enemy had still come through the line of newly dug pits and past the arrows to hack at the English men-at-arms, and how, by the battle’s end, there were no arrows left, just archers with bleeding fingers and a long hill of dying men and animals. The very sky had seemed rinsed with blood.

The telling of the tale took Thomas down off the ridge and out of sight of Durham. Eleanor and Father Hobbe walked behind, leading the mare and sometimes interjecting with their own comments, while a score of Lord Outhwaite’s retainers rode on either side to listen to the battle’s tale. Thomas told it well and it was plain Lord Outhwaite liked him; Thomas of Hookton had always possessed a charm that had protected and recommended him, even though it sometimes made men like Sir Geoffrey Carr jealous. Sir Geoffrey had ridden ahead and, when Thomas reached the water meadows where the English force gathered, the knight pointed at him as if he were launching a curse and Thomas countered by making the sign of the cross. Sir Geoffrey spat.

Lord Outhwaite scowled at the Scarecrow. ‘I have not forgotten the letter your priest showed me’ – he spoke to Thomas in French now – ‘but I trust you will not leave us to deliver it to Durham yourself? Not while we have enemies to fight?’

‘Can I stand with your lordship’s archers?’ Thomas asked.

Eleanor hissed her disapproval, but both men ignored her. Lord Outhwaite nodded his acceptance of Thomas’s offer, then gestured that the younger man should climb down from the horse. ‘One thing does puzzle me, though,’ he went on, ‘and that is why our lord the King should entrust such an errand to one so young.’

‘And so base born?’ Thomas asked with a smile, knowing that was the real question Lord Outhwaite had been too fastidious to ask.

His lordship laughed to be found out. ‘You speak French, young man, but carry a bow. What are you? Base or well born?’

‘Well enough, my lord, but out of wedlock.’

‘Ah!’

‘And the answer to your question, my lord, is that our lord the King sent me with one of his chaplains and a household knight, but both caught a sickness in London and that is where they remain. I came on with my companions.’

‘Because you were eager to speak with this old monk?’

‘If he lives, yes, because he can tell me about my father’s family. My family.’

‘And he can tell you about this treasure, this thesaurus. You know of it?’

‘I know something of it, my lord,’ Thomas said cautiously.

‘Which is why the King sent you, eh?’ Lord Outhwaite queried, but did not give Thomas time to answer the question. He gathered his reins. ‘Fight with my archers, young man, but take care to stay alive, eh? I would like to know more of your thesaurus. Is the treasure really as great as the letter says?’

Thomas turned away from the ragged-haired Lord Outhwaite and stared up the ridge where there was nothing to be seen now except the bright-leaved trees and a thinning plume of smoke from the burned-out hovels. ‘If it exists, my lord’ – he spoke in French – ‘then it is the kind of treasure that is guarded by angels and sought by demons.’

‘And you seek it?’ Lord Outhwaite asked with a smile.

Thomas returned the smile. ‘I merely seek the Prior of Durham, my lord, to give him the bishop’s letter.’

‘You want Prior Fossor, eh?’ Lord Outhwaite nodded towards a group of monks. ‘That’s him over there. The one in the saddle.’ He had indicated a tall, white-haired monk who was astride a grey mare and surrounded by a score of other monks, all on foot, one of whom carried a strange banner that was nothing but a white scrap of cloth hanging from a painted pole. ‘Talk to him,’ Lord Outhwaite said, ‘then seek my flag. God be with you!’ He said the last four words in English.

‘And with your lordship,’ Thomas and Father Hobbe answered together.

Thomas walked towards the Prior, threading his way through archers who clustered about three wagons to receive spare sheaves of arrows. The small English army had been marching towards Durham on two separate roads and now the men straggled across fields to come together in case the Scots descended from the high ground. Men-at-arms hauled mail coats over their heads and the richer among them buckled on whatever pieces of plate armour they owned. The army’s leaders must have had a swift conference for the first standards were being carried northwards, showing that the English wanted to confront the Scots on the higher ground of the ridge rather than be attacked in the water meadows or try to reach Durham by a circuitous route. Thomas had become accustomed to the English banners in Brittany, Normandy and Picardy, but these flags were all strange to him: a silver crescent, a brown cow, a blue lion, the Scarecrow’s black axe, a red boar’s head, Lord Outhwaite’s scallop-emblazoned cross and, gaudiest of all, a great scarlet flag showing a pair of crossed keys thickly embroidered in gold and silver threads. The prior’s flag looked shabby and cheap compared to all those other banners for it was nothing but a small square of frayed cloth beneath which the prior was working himself into a frenzy. ‘Go and do God’s work,’ he shouted at some nearby archers, ‘for the Scots are animals! Animals! Cut them down! Kill them all! God will reward each death! Go and smite them! Kill them!’ He saw Thomas approaching. ‘You want a blessing, my son? Then God give strength to your bow and add bite to your arrows! May your arm never tire and your eye never dim. God and the saints bless you while you kill!’

Thomas crossed himself then held out the letter. ‘I came to give you this, sir,’ he said.

The prior seemed astonished that an archer should address him so familiarly, let alone have a letter for him and at first he did not take the parchment, but one of his monks snatched it from Thomas and, seeing the broken seal, raised his eyebrows. ‘My lord the bishop writes to you,’ he said.

‘They are animals!’ the prior repeated, still caught up in his peroration, then he realized what the monk had said. ‘My lord bishop writes?’

‘To you, brother,’ the monk said.

The prior seized the painted pole and dragged the makeshift banner down so it hung near to Thomas’s face. ‘You may kiss it,’ he said grandly.

‘Kiss it?’ Thomas was quite taken aback. The ragged cloth, now it was close by his nose, smelt musty.

‘It is St Cuthbert’s corporax cloth,’ the prior said excitedly, ‘taken from his tomb, my son! The blessed St Cuthbert will fight for us! The very angels of heaven will follow him into the battle.’

Thomas, faced with the saint’s relic, went to his knees and drew the cloth to his lips. It was linen, he thought, and now he could see it was embroidered about its edge with an intricate pattern in faded blue thread. In the centre of the cloth, which was used during Mass to hold the wafers, was an elaborate cross, embroidered in silver threads that scarcely showed against the frayed white linen. ‘It is really St Cuthbert’s cloth?’ he asked.

‘His alone!’ the prior exclaimed. ‘We opened his tomb in the cathedral this very morning, and we prayed to him and he will fight for us today!’ The prior jerked the flag up and waved it towards some men-at-arms who spurred their horses northwards. ‘Perform God’s work! Kill them all! Dung the fields with their noxious flesh, water it with their treacherous blood!’

‘The bishop wants this young man to speak with Brother Hugh Collimore,’ the monk who had read the letter now told the prior, ‘and the King wishes it too. His lordship says there is a treasure to be found.’

‘The King wishes it?’ the prior looked in astonishment at Thomas. ‘The King wishes it?’ he asked again and then he came to his senses and realized there was great advantage in royal patronage and so he snatched the letter and read it himself, only to find even more advantage than he had anticipated. ‘You come in search of a great thesaurus?’ he asked Thomas suspiciously.

‘So the bishop believes, sir,’ Thomas responded.

‘What treasure?’ the prior snapped and all the monks gaped at him as the notion of a treasure momentarily made them forget the proximity of the Scottish army.

‘The treasure, sir’ – Thomas avoided giving a truthful answer – ‘is known to Brother Collimore.’

‘But why send you?’ the prior asked, and it was a fair question for Thomas looked young and possessed no apparent rank.

‘Because I have some knowledge of the matter too,’ Thomas said, wondering if he had said too much.

The prior folded the letter, inadvertently tearing off the seal as he did so, and thrust it into a pouch that hung from his knotted belt. ‘We shall talk after the battle,’ he said, ‘and then, and only then, I shall decide whether you may see Brother Collimore. He is sick, you know? Ailing, poor soul. Maybe he is dying. It may not be seemly for you to disturb him. We shall see, we shall see.’ He plainly wanted to talk to the old monk himself and so be the sole possessor of whatever knowledge Collimore might have. ‘God bless you, my son,’ the prior dismissed Thomas, then hoisted his sacred banner and hurried north. Most of the English army was already climbing the ridge, leaving only their wagons and a crowd of women, children and those men too sick to walk. The monks, making a procession behind their corporax cloth, began to sing as they followed the soldiers.

Thomas ran to a cart and took a sheaf of arrows, which he thrust into his belt. He could see that Lord Outhwaite’s men-at-arms were riding towards the ridge, followed by a large group of archers. ‘Maybe the two of you should stay here,’ he said to Father Hobbe.

‘No!’ Eleanor said. ‘And you should not be fighting.’

‘Not fight?’ Thomas asked.

‘It is not your battle!’ Eleanor insisted. ‘We should go to the city! We should find the monk.’

Thomas paused. He was thinking of the priest who, in the swirl of fog and smoke, had killed the Scotsman and then spoken to him in French. I am a messenger, the priest had said. ‘Je suis un avant-coureur,’ had been his exact words and an avant-coureur was more than a mere messenger. A herald, perhaps? An angel even? Thomas could not drive away the image of that silent fight, the men so ill matched, a soldier against a priest, yet the priest had won and then had turned his gaunt, bloodied face on Thomas and announced himself: ‘Je suis un avant-coureur.’ It was a sign, Thomas thought, and he did not want to believe in signs and visions, he wanted to believe in his bow. He thought perhaps Eleanor was right and that the conflict with its unexpected victor was a sign from heaven that he should follow the avant-coureur into the city, but there were also enemies up on the hill and he was an archer and archers did not walk away from a battle. ‘We’ll go to the city,’ he said, ‘after the fight.’

‘Why?’ she demanded fiercely.

But Thomas would not explain. He just started walking, climbing a hill where larks and finches flitted through the hedges and fieldfares, brown and grey, called from the empty pastures. The fog was all gone and a drying wind blew across the Wear.

And then, from where the Scots waited on the higher ground, the drums began to beat.

Sir William Douglas, Knight of Liddesdale, prepared himself for battle. He pulled on leather breeches thick enough to thwart a sword cut and over his linen shirt he hung a crucifix that had been blessed by a priest in Santiago de Compostela where St James was buried. Sir William Douglas was not a particularly religious man, but he paid a priest to look after his soul and the priest had assured Sir William that wearing the crucifix of St James, the son of thunder, would ensure he received the last rites safe in his own bed. About his waist he tied a strip of red silk that had been torn from one of the banners captured from the English at Bannockburn. The silk had been dipped in the holy water of the font in the chapel of Sir William’s castle at Hermitage and Sir William had been persuaded that the scrap of silk would ensure victory over the old and much hated enemy.

He wore a haubergeon taken from an Englishman killed in one of Sir William’s many raids south of the border. Sir William remembered that killing well. He had seen the quality of the Englishman’s haubergeon at the very beginning of the fight and he had bellowed at his men to leave the fellow alone, then he had cut the man down by striking at his ankles and the Englishman, on his knees, had made a mewing sound that had made Sir William’s men laugh. The man had surrendered, but Sir William had cut his throat anyway because he thought any man who made a mewing sound was not a real warrior. It had taken the servants at Hermitage two weeks to wash the blood out of the fine mesh of the mail. Most of the Scottish leaders were dressed in hauberks, which covered a man’s body from neck to calves, while the haubergeon was much shorter and left the legs unprotected, but Sir William intended to fight on foot and he knew that a hauberk’s weight wearied a man quickly and tired men were easily killed. Over the haubergeon he wore a full-length surcoat that showed his badge of the red heart. His helmet was a sallet, lacking any visor or face protection, but in battle Sir William liked to see what his enemies to the left and right were doing. A man in a full helm or in one of the fashionable pig-snouted visors could see nothing except what the slit right in front of his eyes let him see, which was why men in visored helmets spent the battle jerking their heads left and right, left and right, like a chicken among foxes, and they twitched until their necks were sore and even then they rarely saw the blow that crushed their skulls. Sir William, in battle, looked for men whose heads were jerking like hens, back and forth, for he knew they were nervous men who could afford a fine helmet and thus pay a finer ransom. He carried his big shield. It was really too heavy for a man on foot, but he expected the English to loose their archery storm and the shield was thick enough to absorb the crashing impact of yard-long, steel-pointed arrows. He could rest the foot of the shield on the ground and crouch safe behind it and, when the English ran out of arrows, he could always discard it. He carried a spear in case the English horsemen charged, and a sword, which was his favourite killing weapon. The sword’s hilt encased a scrap of hair cut from the corpse of St Andrew, or at least that was what the pardoner who had sold Sir William the scrap had claimed.

Robbie Douglas, Sir William’s nephew, wore mail and a sallet, and carried a sword and shield. It had been Robbie who had brought Sir William the news that Jamie Douglas, Robbie’s older brother, had been killed, presumably by the Dominican priest’s servant. Or perhaps Father de Taillebourg had done the killing? Certainly he must have ordered it. Robbie Douglas, twenty years old, had wept for his brother. ‘How could a priest do it?’ Robbie had demanded of his uncle.

‘You have a strange idea of priests, Robbie,’ Sir William had said. ‘Most priests are weak men given God’s authority and that makes them dangerous. I thank God no Douglas has ever put on a priest’s robe. We’re all too honest.’

‘When this day’s done, uncle,’ Robbie Douglas said, ‘you’ll let me go after that priest.’

Sir William smiled. He might not be an overtly religious man, but he did hold one creed sacred and that was that any family member’s murder must be avenged and Robbie, he reckoned, would do vengeance well. He was a good young man, hard and handsome, tall and straightforward, and Sir William was proud of his youngest sister’s son. ‘We’ll talk at day’s end,’ Sir William promised him, ‘but till then, Robbie, stay close to me.’

‘I will, uncle.’

‘We’ll kill a good few Englishmen, God willing,’ Sir William said, then led his nephew to meet the King and to receive the blessing of the royal chaplains.

Sir William, like most of the Scottish knights and chieftains, was in mail, but the King wore French-made plate, a thing so rare north of the border that men from the wild tribes came to stare at this sun-reflecting creature made of moving metal. The young King seemed just as impressed for he took off his surcoat and walked up and down admiring himself and being admired as his lords came for a blessing and to offer advice. The Earl of Moray, whom Sir William believed was a fool, wanted to fight on horseback and the King was tempted to agree. His father, the great Robert the Bruce, had beaten the English at the Bannockburn on horseback, and not just beaten them, but humiliated them. The flower of Scotland had ridden down the nobility of England and David, King now of his father’s country, wanted to do the same. He wanted blood beneath his hooves and glory attached to his name; he wanted his reputation to spread through Christendom and so he turned and gazed longingly at his red and yellow painted lance propped against the bough of an elm.

Sir William Douglas saw where the King was looking. ‘Archers,’ he said laconically.

‘There were archers at the Bannockburn,’ the Earl of Moray insisted.

‘Aye, and the fools didn’t know how to use them,’ Sir William said, ‘but you can’t depend on the English being fools for ever.’

‘And how many archers can they have?’ the Earl asked. ‘There are said to be thousands of bowmen in France, hundreds more in Brittany and as many again in Gascony, so how many can they have here?’

‘They have enough,’ Sir William growled curtly, not bothering to hide the contempt he felt for John Randolph, third Earl of Moray. The Earl was just as experienced in war as Sir William, but he had spent too long as a prisoner of the English and the consequent hatred made him impetuous.

The King, young and inexperienced, wanted to side with the Earl whose friend he was, but he saw that his other lords were agreeing with Sir William who, though he held no great title nor position of state, was more battle-hardened than any man in Scotland. The Earl of Moray sensed that he was losing the argument and he urged haste. ‘Charge now, sir,’ he suggested, ‘before they can make a battleline.’ He pointed southwards to where the first English troops were appearing in the pastures. ‘Cut the bastards down before they’re ready.’

‘That,’ the Earl of Menteith put in quietly, ‘was the advice given to Philip of Valois in Picardy. It didn’t serve there and it won’t serve here.’

‘Besides which,’ Sir William Douglas remarked caustically, ‘we have to contend with stone walls.’ He pointed to the walls which bounded the pastures where the English were beginning to form their line. ‘Maybe Moray can tell us how armoured knights get past stone walls?’ he suggested.

The Earl of Moray bridled. ‘You take me for a fool, Douglas?’

‘I take you as you show yourself, John Randolph,’ Sir William answered.

‘Gentlemen!’ the King snapped. He had not noticed the stone walls when he formed his battleline beside the burning cottages and the fallen cross. He had only seen the empty green pastures and the wide road and his even wider dream of glory. Now he watched the enemy straggle from the far trees. There were plenty of archers coming, and he had heard how those bowmen could fill the sky with their arrows and how their steel arrow heads drove deep into horses and how the horses then went mad with pain. And he dared not lose this battle. He had promised his nobles that they would celebrate the feast of Christmas in the hall of the English King in London and if he lost then he would lose their respect and encourage some to rebellion. He had to win and, being impatient, he wanted to win quickly. ‘If we charge fast enough,’ he suggested tentatively, ‘before they all reach their lines—’

‘Then, you’ll break your horse’s legs on the stone walls,’ Sir William said with scant respect for his royal master. ‘If your majesty’s horse even gets that far. You can’t protect a horse from arrows, sir, but you can weather the storm on foot. Put your pikes up front, but mix them with men-at-arms who can use their shields to protect the pike-holders. Shields up, heads down and hold hard, that’s how we win this.’

The King tugged at the espalier which covered his right shoulder and had an annoying habit of riding up on the top edge of the breastplate. Traditionally the defence of Scottish armies was in the hands of pikemen who used their monstrously long weapons to hold off the enemy knights, but pikemen needed both hands to hold their unwieldy blades and so became easy targets for English bowmen who liked to boast that they carried the lives of Scottish pikemen in their arrow bags. So protect the pikemen with the shields of the men-at-arms and let the enemy waste their arrows. It made sense, but it still irked David Bruce that he could not lead his horsemen in an earth-shaking assault while the trumpets screamed at the heavens.

Sir William saw his King’s hesitation and pressed his argument. ‘We have to stand, sir, and we have to wait, and we have to let our shields take the arrows, but in the end, sir, they’ll tire of wasting shafts and they’ll come to the attack and that’s when we’ll chop them down like dogs.’

A growl of assent greeted this. The Scottish lords, hard men all, armed and armoured, bearded and grim, were confident that they could win this fight because they so outnumbered the enemy, but they also knew there was no short cut to victory, not when archers opposed them, and so they would have to do what Sir William said: endure the arrows, goad the enemy, then give them slaughter.

The King heard his lords agree with Sir William and so, reluctantly, he abandoned his dream of breaking the enemy with mounted knights. That was a disappointment, but he looked about his lords and thought that with such men beside him he could not possibly lose. ‘We shall fight on foot,’ he decreed, ‘and chop them down like dogs. We shall slaughter them like whipped puppies!’ And afterwards, he thought, when the survivors were fleeing southwards, the Scottish cavalry could finish the slaughter.

But for now it would be footman against footman and so the war banners of Scotland were carried forward and planted across the ridge. The burning cottages were mere embers now that cradled three shrunken bodies, black and small as children, and the King planted his flags close to those dead. He had his own standard, red saltire on yellow field, and the banner of Scotland’s saint, white saltire on blue, in the line’s centre and to left and right the flags of the lesser lords flew. The lion of Stewart brandished its blade, the Randolph falcon spread its wings while to east and west the stars and axes and crosses snapped in the wind. The army was arrayed in three divisions, called sheltrons, and the three sheltrons were so large that the men on the far flanks jostled in towards the centre to keep themselves on the flatter ground of the ridge’s summit.

The rearmost ranks of the sheltrons were composed of the tribesmen from the islands and the north, men who fought bare-legged, without metal armour, wielding vast swords that could club a man to death as easily as cut him down. They were fearsome fighters, but their lack of armour made them horribly vulnerable to arrows and so they were placed at the rear and the leading ranks of the three sheltrons were filled by men-at-arms and pikemen. The men-at-arms carried swords, axes, maces or war-hammers and, most important, the shields that could protect the pikemen whose weapons were tipped with a spike, a hook and an axehead. The spike could hold an enemy at bay, the hook could haul an armoured man out of the saddle or off his feet, and the axe could smash through his mail or plate. The line bristled with the pikes that made a steel hedge to greet the English and priests walked along the hedge consecrating the weapons and the men who held them. Soldiers knelt to receive their blessings. A few of the lords, like the King himself, were mounted, but only so that they could see over the heads of their army, and those men stared south to see the last of the English troops come into view. So few of them! Such a small army to beat! To the left of the Scots was Durham, its towers and ramparts thick with folk watching the battle, and in front was this small army of Englishmen who did not possess the sense to retreat south towards York. They would fight on the ridge instead and the Scots had the advantage of position and numbers. ‘If you hate them!’ Sir William Douglas shouted at his men on the right of the Scottish battleline, ‘then let them hear you!’

The Scots bellowed their hatred. They clashed swords and spears against their shields, they shrieked to the sky and, in the line’s centre, where the King’s sheltron waited under the banners of the cross, a troop of drummers began to beat huge goatskin drums. Each drum was a big ring of oak over which were stretched two goat skins that were tightened with ropes until an acorn, dropped onto a skin, would bounce as high as the hand that had let it go and the drums, beaten with withies, made a sharp, almost metallic sound that filled the sky. They made an assault of pure noise.

‘If you hate the English, let them know!’ the Earl of March shouted from the left of the Scottish line that lay closest to the city. ‘If you hate the English, let them know!’ and the roar became louder, the clash of spear stave on shield was stronger, and the noise of Scotland’s hate spread across the ridge so that nine thousand men were howling at the three thousand who were foolish enough to confront them.

‘We shall cut them down like stalks of barley,’ a priest promised, ‘we shall soak the fields with their stinking blood and fill all hell with their English souls.’

‘Their women are yours!’ Sir William told his men. ‘Their wives and their daughters will be your toys tonight!’ He grinned at his nephew Robbie. ‘You’ll have your pick of Durham’s women, Robbie.’

‘And London’s women,’ Robbie said, ‘before Christmas.’

‘Aye, them too,’ Sir William promised.

‘In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost,’ the King’s senior chaplain shouted, ‘send them all to hell! Each and every foul one of them to hell! For every Englishman you kill today means a thousand less weeks in purgatory!’

‘If you hate the English,’ Lord Robert Stewart, Steward of Scotland and heir to the throne, called, ‘let them hear!’ And the noise of that hate was like a thunder that filled the deep valley of the Wear, and the thunder reverberated from the crag where Durham stood and still the noise swelled to tell the whole north country that the Scots had come south.

And David, King of those Scots, was glad that he had come to this place where the dragon cross had fallen and the burning houses smoked and the English waited to be killed. For this day he would bring glory to St Andrew, to the great house of Bruce, and to Scotland.