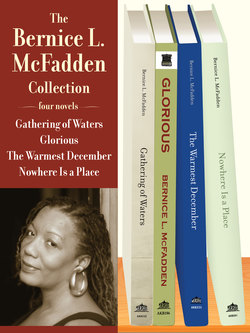

Читать книгу The Bernice L. McFadden Collection - Bernice L. McFadden - Страница 59

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

Part vaudeville act, part circus, Slocum’s Traveling Brigade crisscrossed backwoods America, entertaining Negroes barely forty years free of slavery who were uneducated hard workingmen and -women who, when told to sign on the dotted line, all had the same name: X.

They went to the jig show, clutching their nickels and pennies. The men tucked pints of moonshine safely into the back pockets of their overalls and wore their straw hats slung back on their heads, as they looked on in awe at the fire-eating Indian, the counting goat, and the magician who made a raccoon disappear right before their very eyes.

Easter, leaving but not really heading anywhere in particular, with anger lodged in her throat like a peach pit, marched right past the brigade and then doubled back. She paid her nickel and found herself in the midst of the adults-only midnight ramble, so called because the female performers often stripped out of their clothes.

Easter planted herself between two men. The one to her right was a grizzled old guy who smelled of wet earth. He stood slump-shouldered with his hands shoved deep into the pockets of his pants. His fingers wiggled beneath the material, in search of something Easter was more than sure wasn’t coins. The man to her left was long and lanky, with eyes that bulged unnaturally from their sockets, veiling him with a comical jig-a-boo look the white folks caricatured in their daily newspapers.

The members of the three-piece jug band climbed onto the wooden stage and peered put at the audience. A young boy moved along the row of oil lamps carefully igniting their wicks.

Slocum, the short, round, dimple-cheeked proprietor, bounded onto the stage and cast his toothless grin over the crowd before joyfully announcing: “Women hold onto your husbands, men hold tight to your hats, a storm is coming that I guarantee will leave you soaking wet!”

The audience tensed.

“Put your hands together for Mama Raaaaiiiiin!”

The jug band struck up. Fingers covered in thimbles glided down the belly of a washboard, lips blew breath over the ceramic mouth of the whiskey jug, a pick plucked banjo strings, and two pewter spoons angrily conversed. Combined the sounds created music, and Easter began to tap her foot against the sawdust-littered ground. The audience swayed in unison, becoming one living, breathing, rhythmic organ, and then Mama Rain sauntered onto the stage and everyone went still.

Six-foot, red-boned, green-eyed, Geechee girl with close-cut curls the color of straw. She was barefoot and Easter thought that Rain had the prettiest toes she had ever seen. She wore a yellow-feathered boa coiled around her neck.

The music climbed and Rain began to dance, to shimmy and shake, and with every lunge, every hop, the peach pit in Easter’s throat began to break apart, to disintegrate into dust. Her mouth went dry and her tongue withered like a tuber left out beneath a blazing, midday sun.

Rain tossed her head seductively to one side, kicked her leg out, pulled it back, rolled her hips, took three dainty steps toward the edge of the stage, and bent over the crowd so that the tops of her breasts peeked above the jewel neckline of the orange silk shift she wore. Mama Rain offered a girlish grin as her shoulders caught the rising melody of the angry pewter spoons. Up in the air now, square with her perfect ears, they began to pump. No one was ready for the next thing that happened. Mama Rain straightened her back, placed her hands on her hips, and with one sudden visceral move she sent her groin forward. The thrust was accentuated by the thundering sound of the band members’ heavy boots crashing down onto the stage floor. Two men standing in the front row fell backwards, as if hit by an invisible battering ram. Another thrust and three more men crumbled.

Mama Rain clasped her hands behind her head, curled her mouth into a devious smile, and threw her pelvis forward again, sending five men to their knees and striking Easter with a thirst that she would soon realize a hundred tin cups of water would never satisfy.

When it was all said and done, Rain was soaking wet, the thin shift cleaved to her body, outlining every luscious curve. Easter heard someone whisper, “My Lord,” in a sinful and dirty way, and when she looked around to see who had uttered the sacrilegious statement, two sets of eyes were staring right back at her. Easter clamped her hand over her mouth, turned, and fled.

***

Easter didn’t have a plan or a place to go and so she hung around the brigade grounds, hoping to catch sight of Rain one last time, but she had disappeared and had not reemerged. Easter tried to look as inconspicuous as possible lugging that brown suitcase and dressed in a blue and white dress that made her look like a schoolgirl on the run. She tried to blend, but instead she stuck out like a snowflake in a vat of coal.

“Ain’t you got no place to go?”

Easter spun around and found herself eye to eye with Slocum. He considered her, and she took in his blistered lip and heavy eyelashes.

“I need a job.” The words jumped out of her mouth and landed on the ground between them. Slocum grunted, slipped his hands behind the bib of the overalls he wore, and rocked back on his heels.

“Oh, really now? What you do?”

Easter shrugged her shoulders. “This and that.”

“This and that? Well that’s just what we been looking for!” Slocum clapped his hands together and laughed. “Go on home now, ain’t nothing here for you.” He dismissed her with a quick wave of his hand.

“I—I can cook and clean.”

Slocum was walking away. “Can’t use you,” he threw over his shoulder.

“The hell you can’t!” The unmistakable voice boomed behind Easter causing her heart to lurch in her chest. Slocum turned around, an annoyed smirk resting on his lips. “Bennie like to kill me with his cooking, we need a feminine touch. I’m tired of eating lumpy grits and undercooked eggs. Besides, I need someone to attend to me,” Rain barked.

“Aww, come on, Rain,” Slocum whined, “she just a child—”

“Shut up, she looks pretty grown to me.”

Easter was shaking like a leaf.

“Turn around, sugar, lemme get a look at you.”

Easter turned around. Rain was standing outside of her tent; the silk robe she wore flapped open revealing her naked body. Easter dropped her eyes.

Rain waltzed over and caught her by the chin. “What’s your name, girl?” Her fingers felt like fire against Easter’s skin.

“Easter, ma’am,” she quaked in a timid voice.

Rain’s eyes sparkled. “Easter? That’s a real old-timey name. Had a great-aunt named Easter.” She cackled and released Easter’s chin. “And I ain’t no ma’am.” She spat, then, “You say you cook and clean?”

“Yes m—I mean yes.”

Slocum stepped between the women, wagging his finger in Rain’s face. “We ain’t pulling in enough money to pay and feed another soul, Rain!”

Rain eyed him menacingly. “Nigger, if you don’t get outta my face …” Her words trailed off, but the threat hung heavy in the air.

Slocum’s hand floated back down to his waist and he stepped cautiously to one side.

“I’ll pay her myself, don’t you worry about it, you cheap bastard!” Rain snapped, and then turned and started back toward her tent. Easter just stood there, frozen, watching Rain’s hips sway beneath the fabric of the robe.

“I done told her ’bout talking to me like that,” Slocum grumbled to himself as he kicked at the dirt. “Well what you waiting for, sun-up? Go on, git!”

Easter jumped to life and double-timed to Rain’s tent.

“I want you to know right now that I likes women,” Rain said as she shrugged her robe off and tossed it onto the cot.

Easter’s face unfolded and her stomach clenched. “Not to worry, sugar,” Rain laughed, walking over to Easter and pinching her cheek, “you too young for Mama Rain. I like ’em seasoned and you just out of the shell.” She laughed again and glided to the opposite side of the tent where she squatted daintily over a cream-colored chamber pot and relieved herself. “You still a virgin?” she asked in a non-chalant tone.

As embarrassed as Easter was by the question, she was more than a little disappointed that Rain wouldn’t even consider her as a lover, and then she became angry with herself for wanting such a thing. Easter remained silent.

“Figures.” Rain chuckled, gave her bottom a quick shake, and then stood. “Dump it before this entire tent is rank with the stink of piss.” She pointed to the pot and after a moment’s hesitation Easter hurried to fetch it.

Rain sighed and began to untwine the feather boa from her neck, exposing the keloid scar that looped from one collarbone to the next, resembling a string of brown pearls. Easter’s mouth dropped open and then clamped shut again when Rain turned smoldering eyes on her.

“Well what you gonna do, stand there all night holding my piss?”

“Uhm, no ma’am—I mean no,” she stammered as she backed out of the tent.

Outside Easter moved quickly and recklessly, causing the piss to slosh over the sides, wetting her hands. She was disgusted and intrigued. She looked cautiously around her, and when she saw that no one was watching, she brought her finger to her nose and sniffed. Rain’s piss smelled like gardenias.

Easter would learn that Rain didn’t much like men or the snake that grew down between their legs. It had never been sweet to her, not from the time she was someone’s sweet little girl, with pigtails, living in Louisiana and singing in the choir, just eleven years old when her brother’s best friend cornered her in the outhouse and pressed his forearm against her throat as he rammed himself inside her, all the while whispering in her ear that she had it coming. “This is what happens to cock teasers,” he’d said. Afterwards, he called her a “yella heifer,” while he used his shirttail to wipe her blood from his penis.

Nothing but trouble followed the men that came later and Hemp Jackson was trouble with a capital T. As mean and black as the day was long, Hemp had the body of a bulldog and his right eye was a cloud of cotton. He chose not to wear an eye patch; he liked the hideous look that damaged eye graced him with and the fear it struck in the hearts of men. He claimed that Rain was the only woman he’d ever loved and gave her a feathered boa to prove it, which turned out to be a poor substitute for an apology, since he was the one who’d sliced her neck in the first place. After that there had been a period of gentleness from a soft-spoken man with kind eyes. That relationship had produced a son who after two months Rain had wrapped in a blanket, placed in a basket, and left on the front porch for the soft-spoken man’s wife to raise. Then she walked right out of that life without even so much as a goodbye to her parents.

Rain didn’t like men, which made it easy for her to shake her ass and roll her hips for them. It was the women she loved.

At night, Mama Rain would stretch herself out on her cot, naked except for the boa, and she’d smoke and sip from her flask of white lightning and talk about all the good and bad that had been done to her, the whole while absentmindedly stroking the hairs of the triangle of black hair between her legs. When she caught Easter staring, which was often, she would snort, “This here my cat, I got a right to pet it.” And then she would laugh, long and hard, until the laughter became a chuckle and the chuckle became a snore and the empty flask fell down to the sawdust floor.

Show after show and night after night, through downpour and drought, snow and clover, Easter’s thirst for Rain swelled and so she reached for her Bible and plunged herself into Scripture, and when that didn’t work she turned to her own words. But words—anointed or not—offered no solace and absolutely no quench.