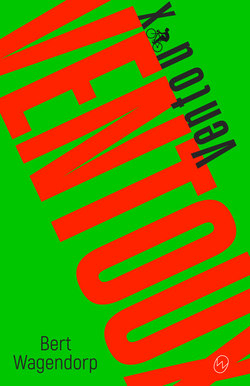

Читать книгу Ventoux - Bert Wagendorp - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление-

VI

I gazed at the short blond hair of Marga Sap in front of me. A gold chain glittered through it. She was wearing a tight black sweater and I had to restrain myself not to stroke her neck with one finger.

It was the end of August 1978, Gerrie Knetemann had just become world champion, and Karel Giesma the maths teacher was talking about p-adic numbers. I tried to make myself invisible in order to avoid questions. The dark universe in which he moved was not mine.

Next to me, Joost was adding moustaches and glasses to the pop musicians in his diary—most of them already had moustaches anyway. He also drew in text balloons. He was bored, and Giesma couldn’t tell him anything new. Joost was one of those people for whom the logic of numbers and lines held no secrets. He read Pythagoras Magazine.

He stopped drawing and nudged me.

‘Someone winds a thread round the earth,’ he whispered. ‘And so does someone else, only he doesn’t lay the thread on the ground but hangs it one metre high. Yes?’

I nodded with as little interest as possible.

‘Right. Now the question is: how much more string does the second man need than the first?’

‘No idea. It’s impossible. What do they do with the oceans?’

‘What matters is the principle. This is an experiment in thinking. Well?’

‘Ten thousand kilometres.’

‘Oh no. A little over six metres!’

‘It’s impossible.’

‘One man needs a length of 2 π r and the other one of 2 π r plus 1 metre. That makes 2 π metres. Say about six metres. Nice, isn’t it? Now we’ll do the same with the circumference of your prick.’

Marga Sap turned round. She didn’t understand a thing about maths either.

‘The circumference of my prick?’

‘That’s different from the length, dickhead. Someone winds a string round it, and someone else does the same, but at a distance of one metre. How much more string does he need?’

‘Christ, Joost, shut up for a minute.’

‘Also 2 π metres,’ he said triumphantly, and wrote something in the text balloon above the head of Freddie Mercury. Freddie already had a pipe in his mouth.

‘I want to fuck Marga Sap,’ said Freddie Mercury.

‘Hoffman, stop that stupid laughing,’ warned Giesma. He was chalking secret codes on the board.

I was wearing my black Levis and the Michigan State T-shirt my cousin had sent me. It was Thursday, and after maths I had to dash to the music school for my organ lesson, for which, as usual, I hadn’t practised.

Everything happens simultaneously; time is no more than an ordering, an illusion. Joost says that time doesn’t exist, André has a painting on the wall about movement that is stasis, while I’m trying to make time stand still. Our friend Peter had to knock on the door of the love cabins on his father’s brothel boat when time was up. There were men who only came when he knocked. One of his poems is called ‘Love is Time’.

I hummed ‘You’re The One That I Want’ softly in Marga’s ear. The nape of her neck went slightly red. I’ll just run my finger along Marga’s chain, play a little with her blond hair, blow on her neck for a moment—and who knows but she might fall in love with me.

Then there was a loud bang on the door of the classroom. Giesma dropped the chalk in shock. Marga turned round with a questioning look in her eyes, as if she could feel what I was planning.

‘Open ze door!’ yelled André from the back of the class. Joost dropped forward laughing, with his face in his arms. Giesma went to the door and, for a second, checked that his bow tie was straight. Berghout, the principal, peered into the classroom, the strands of hair falling across his balding head, and grinned with satisfaction at the effect of his sledgehammer blow.

Next to him stood a black boy.

‘Come in,’ said Giesma.

Berghout went over to the spot behind the teacher’s desk, followed by the black boy, who was wearing a shiny light-blue shirt and trousers with wide legs that had a slight sheen and a red stripe down the side. He swung his hips loosely.

‘Boney M,’ whispered Joost.

The boy seemed shy, yet at the same time exuded self-confidence.

Marga turned round to me again. Her beautiful lips formed three excited words: ‘He’s black!’

‘No, he’s an Eskimo,’ I whispered back.

The headmaster looked at the class and said nothing, obviously wanting to give us time to absorb this historic moment.

‘Class,’ said Berkhout, I’d like to introduce you to David Castelen. He’s from Paramaribo and recently came to live here. From today David will be a member of your class. I’m counting on you to show him the ropes and make sure he soon feels at home in our school. Anyone got any questions?’

No questions.

‘David, any questions?’

‘No, I don’t have any questions.’

‘Good. Then Mr Giesma will assign you a seat and you can quickly brush up your knowledge of Dutch mathematics.’

‘I hope it isn’t as hard as the Surinamese kind.’ There was laughter. Giesma pointed him to the empty spot next to André, at the back of the class. David walked over to it like Elvis Presley going on stage, with swinging hips.

Joost looked at me and made significant movements with his eyebrows. ‘Seems okay,’ he whispered.

I nodded. ‘What do you think, is he gay?’

‘Blacks are never gay, didn’t you know that? They’re far too big to be gay. The other gays can’t take it.’

I saw a new red blush in the nape of Marga Sap’s neck—obviously she hadn’t known that before either.

David’s father had a small travel agency in the Lange Hofstraat, the East-West Travel Agency. Castelen Senior himself had a deep-seated dislike of travelling, including holidays. He had come to the Netherlands because of the future of his children and, in so doing, he had used up all his wanderlust for the rest of his life.

The family home was above the travel agency, so that the life of father Castelen, who had the whole world on offer to his customers, was confined largely to an area of ten by ten by five metres.

‘I can’t understand those people,’ he said. ‘What’s the point of going to a lousy country like that? You catch diseases, the food is terrible, your daughter is attacked, and there’s nothing better to do than slump in a deckchair on the beach. It would be going too far to advise people to stay at home, I’ve got to get by but I can’t make head or tail of it. East, west, home is best, I always say.’ He thought the name of his travel agency was a good joke.

David had inherited his father’s lack of desire for displacement. A year after they had arrived, you could say with certainty that they would never leave, and that in three hundred years’ time, the tenth generation of Castelens would still be living quite contentedly in the town.

When David was 17, he worked out that it was time to sell what he called ‘Adventure Trips’. The first Adventure Trip that the East-West Travel Agency offered was to Lapland. There, the holidaymakers had to trudge for days from hut to hut while being bitten to death by mosquitoes and surviving on berries and whatever provisions they had brought with them.

At first, old Castelen couldn’t see the point. ‘You might as well start selling torture.’ But David maintained stubbornly that, on the contrary, people needed a portion of real misery. As long as they could see an end to it, and could come home again safely after a short while and tell heroic tales. Finally, his father agreed.

David wrote an advertisement for the local paper about the Adventure Trip to the Far North, in which he described ‘the bellowing of the elks’, ‘the fascinating Northern Lights’ and ‘the age-old customs and richly coloured splendour of the Lapps.’ The trip was booked up within six days. Castelen Senior found it irresistibly funny that his customers would soon simply bump into their neighbours instead of a bellowing elk.

‘All the better,’ said David. ‘People like that.’

‘They’ve all gone crazy. But they’re getting what they want.’

And so East-West Travel Agency acquired another arm, Eastwest Adventures, headed by the world’s biggest home-body, David Castelen.

I didn’t have to look up David on a university website or use a lawyer. I saw him whenever I was in Zutphen, about three times a year, to visit my father when he was still alive, or when I was in the area for the paper.

After an hour or so I could hear my Eastern accent re-emerging, as if my tongue was glad to be able to form the innate sounds once more. Every so often the thought of returning resurfaced. Like the Greek emigrant who has made a pile in America and, after completing the task, returns to his village on an island in the Ionian Sea. Old Hoffman, who has seen the world, has become wise and returns to his roots. It would be nice if André and Joost did the same, then we could play cards in Annie & Wim’s café.

In the thirty-five years that David had lived in the town, he had succeeded in becoming a full-blooded Easterner. He spoke to the people who came to his travel agency in faultless dialect and no one thought it was odd.

He still lived above the shop, and the Adventure Trips were his best-selling line. He had profited from growing prosperity and boredom. One of his most successful trips was a two-week trek through Suriname, with overnight accommodation in bushmen’s huts and including a day’s piranha fishing. He also dropped people off in the Alaskan wilderness. Oddly enough, the demand for that trip had increased after one of his customers had only just survived an attack by a grizzly bear.

‘People are getting more and more demanding,’ he said. ‘It’s no longer enough to give them a walk through a desert full of scorpions or a survival trail through the jungle with rickety hanging bridges over crocodile-infested rivers. These days, they find that on the dreary side. Hang-gliding at the North Pole, a voyage to the Canaries in a leaky WWII German submarine, that’s the kind of thing you’ve got to come up with. There was someone here the other day who had read Moby Dick. Wanted to go whale hunting, expense no object. So I follow it up, and three weeks ago the guy flew to Japan and is now on one of those ships. He said he was going to bring me back a piece of whale meat.’

David has always remained unmarried. We never talk about it. He never asked about my marriage and afterward never about my divorce; I don’t pester him with questions about his bachelor status. We have enough other things to talk about. He is a reader who single-handedly keeps the bookshop of Zutphen in business, and his tastes are diverse. He praises the débuts of writers I have never heard of, and he also recommends obscure Icelanders and biographies of American generals—the Civil War is one of his specialties. He is constantly begging me to read and reread Turgenev. ‘Turgenev is the greatest. Certainly Chekhov comes close, he can also make you smell the steppes. But Turgenev is the only one with whom you can hear the people talking. It’s almost creepy.’

He is a fervent film buff, and in this area, too, he provides me with valuable tips. How he finds the time to read his way through those piles of books, and meanwhile see all those films, is a mystery to me. He says that he reads a lot when there are no customers. ‘Which happens more and more often because of that bloody Internet.’

I had informed David on the phone about my meetings with André and Joost, but he insisted that I come and give him a personal report. ‘I feel a reunion in the air. You can’t talk about that on the telephone. The Beatles never got back together on the telephone.’

‘They never got together again at all.’

‘That’s what I mean. When shall we meet?’

‘Wednesday?’

‘Wednesday.’

On Tuesday he sent me an email.

‘Dear Bart,’ he wrote, ‘so as not to give you a shock tomorrow, I must tell you the following. What happened? I’ve been feeling a bit tired recently, so I figure: let’s go and see the doctor. I see Doctor Coomans. He taps my chest, fishes around a bit over my belly and back with his stethoscope: in perfect shape. Blood pressure. Thing round my arm, pumps it up and lets it down again. Much too high. I’ve got to take medication and lose weight. He asks: do you do any sport? I say: I cycle. No idea why, because I don’t cycle at all. Oh, he says, that’s nice, I cycle too. Sports bike? I say: yes, a racing bike, a Koga. Only make that comes to mind. Fantastic, says the doctor, Sunday morning at 9.30 on ’s Gravenhof in front of Hotel Eden. I go straight to Van Spankeren: I need a Koga. Must it be a Koga? Yes, a Koga. He points to a Koga. Fine, I take that one. Pay out twelve hundred euros and walk out of the shop with a Koga. Plus an outfit. Sunday is the day, I’m dreading it.’

‘Dear David,’ I emailed back, ‘I would have been less surprised if you had acquired a Thai wife. Christ Almighty, the champion of Suriname. We’ll go out for a spin soon.’

‘Definitely,’ he replied. ‘With Joost and André along. Team ride. Ordered a Rapha jersey. Do you know it? Brilliant, absolutely brilliant. Merino wool. And a silk bandana. If I’m going cycling, of course I want to look well groomed. That’s what they call it, isn’t it?’

I forward the email exchange to Joost and André.

I went into the Italian restaurant on the Houtmarkt, where David eats three times a week. He is a man of fixed habits; I didn’t have to look for where he was sitting. He was wearing a light-blue shirt, which combined elegantly with a pair of black trousers and shoes that looked as if they were woven. David orders his shirts from Italy, as well as his handmade shoes. He even travelled especially to Italy to have himself measured to the millimetre, one of the few foreign trips he has made in the last few decades.

‘Bart!’ He got up to shake hands and thump me on the shoulders. ‘Bart, man! A great pleasure to see you here again. This town is a rootless place when you’re not here. When are you coming back for good? Life would gain enormously in quality! Why don’t you set up here as a writer; that would also be very good for the fame of the town.’

David’s words of welcome were lectures, spoken in an Eastern dialect doused with vague memories of Paramaribo, which he laid on extra thick because he knew that it gave me great pleasure.

‘Friend David!’ I said, true to habit. ‘Cycling legend, in what exclusive eatery do we have the pleasure of dining this evening? Do you come here often?’

‘Only three or four times a week,’ he said, beckoning the waiter. ‘Today happens to be my thousandth visit, so I think we shall be lavishly fêted by the owner, who has made a packet off me.’

He ordered a bottle of white house wine. ‘Stick with what you like, is my motto. What do you think?’

‘You’re right.’

He asked me if I had already read Roland Barthes on the Tour de France. I said I had Mythologies on the to-read pile.

Apart from Anna, David was the only one who knew I was working on a book in which I wanted to link cycling and philosophy. To give it a working title, I called it Spinoza on the Bike. I had already read a lot about Spinoza and his views. I had also tried to work my way through the Ethics, but had unfortunately become bogged down.

David had once actually sent me chapter headings: 1. The Bike, Philosophically Analyzed; 2. Philosophizing on the Bike; 3. The Greek Philosophers on the Bike; 4. Kant on the Bike; 5. Merckx’s Tour Victories, Philosophically Analyzed; 6. Armstrong the Philosopher; 7. The Bike as a Means of Transport to the Truth; 8. Sex, Philosophy, and the Bike (plus a Large Beer); 9. How to Seduce Women with Philosophy and the Bike; 10. Reading Hands Free; 11. Nietzsche was a Doper.

With David, you never know if he means something, or if it’s a joke. This was somewhere in the middle, probably. He bombarded me with reading tips for the project. I had the impression that he spent half his time in the travel agency on research for my book.

‘How’s your French? You’ve got to read the new biography of Anquetil. You’ll see the link between behaviour on the bike and view of life brilliantly illustrated. Do you know that Anquetil was disappointed when he won a time trial by twelve seconds? He thought it was eleven seconds too much. Brilliant, isn’t it? You can use that, or can’t you? Or else there are his views on love and sexuality? Haha! And then there’s Peter Sloterdijk, the German philosopher. He’s written very interesting things about …’

‘David, listen. I’m frightened I’ll never get round to writing if I read all these books you’re recommending first. I’ll die reading in bed without having put a single word down on paper.’

He looked at me in disappointment for a moment. Then he turned to the waiter who came to the table to take our order.

‘Two Wednesday, Henk.’

‘Wednesday?’, I asked.

‘Great. You’ll see. I don’t think we’ve ever eaten here on a Wednesday, or have we?’

David picked up the napkin from the table, laid it on his lap, leaned forward slightly, and looked at me. He was already over the disappointment.

‘Bart, you’ll never guess. Who suddenly walked into my place last week? Well?’

‘No idea.’

‘Marga Sap. Marga Sap! An American lady comes into the office, you know, heavy make-up, Botox, and I’m thinking: now what? And suddenly I see it. Marga Sap. Guess what she’s called now?’

‘Haven’t got a clue. Marga Juice?’

‘Marge Armstrong. I swear. Marge Armstrong. Haha!’

‘You’re kidding!’

‘True!’

‘And?’

‘We went for a meal. Here.’

‘Original.’

‘Before that we walked through the town for two hours. She hadn’t been back for at least twenty-five years. She was all eyes.’

‘And then?’

‘After dinner I took her back to her hotel, and she told me what she thought when I came into your class for the first time.’

‘Well?’

‘She’d heard that all black guys have an enormous dong and she thought: there’s one.’

‘Cut it out, David.’

‘So, yes…’

‘No!’

‘Yes. Marga Sap. Finally.’

‘And now?’

‘Now she’s gone back to Jack in Lansing, Michigan. She sends you her best wishes.’