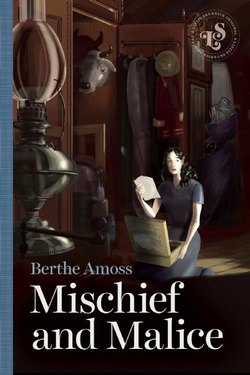

Читать книгу Mischief and Malice - Berthe Amoss - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThree

The next morning when Uncle Henry knocked on my door to wake me for school, I discovered my head felt like a cannon ball, my nose was stopped up, and my throat was scratchy from gasping air through my mouth.

“I’m sick,” I croaked at Uncle Henry. Aunt Toosie came to my room on the double. She felt my head and popped a thermometer in my mouth.

“Close your mouth, dear. Don’t bite the thermometer!”

“I can’t breathe through my nose!” I cried in a panic.

“Don’t talk! You’ll bite the thermometer!” She took it out. “It registers one whole degree above normal already! Stay in bed and I’ll call the doctor. What in the world could you have?”

I knew what I had. I had a terrible cold from driving around with a wet head. Besides the cold symptoms, I had a miserable all-over feeling of hating myself.

I tried to tune in on Aunt Eveline, but she was out. If only I could go back in time. Instead of wasting my days plotting how to get Leonard to notice me, I would answer Tom’s letter. I would tell him all the things he wanted to know, like how his dog was getting along. I would, of course, have been paying more attention to Pumpkin, taking him for a daily walk and giving him bones, and I’d tell Tom how much the football team needed him back, how Harold said he was the best wide receiver they’d ever had, and I’d tell him how happy his mother was that he was doing so well in school up there, and how contented his Uncle Malvern was with the progress he was making on his invention. Naturally, I would be able to say I’d visited Uncle Malvern as often as I could when I wasn’t working at my drawing, practicing to be a famous artist.

“Remorse,” said Aunt Eveline.

“Remorse?”

“Remorse is closely akin to self-pity.” How often Aunt Eveline’s words had blown past me unnoticed as a breeze. “If you don’t change your ways, what good is remorse?”

“I will change my ways! Aunt Eveline, I’ll reform! I’ll put on a new spirit just like Sister Maurice says. I’ll act grown-up and devote myself to art!”

“What did you say, dear?” Aunt Toosie asked, pushing my door open with her hip because in one hand she was carrying a tremendous glass of orange juice over crushed ice and in the other, a small glass chuck full of—milk of magnesia.

“I said, maybe it’s my appendix!” I put my hand on my stomach. “Aunt Eveline used to say you’re not supposed to take milk of magnesia if you have a stomachache.”

Aunt Toosie paused. “You didn’t say you had a stomachache!”

“Ah-de-la-eed! The truth, please!” I heard Aunt Eveline distinctly.

“My stomach’s okay, Aunt Eveline, I’ve paid for my sins.” I gulped down the milk of magnesia and put the orange juice on the table by my bed. “You don’t have to call the doctor, Aunt Toosie. I have a cold because I went to bed with a wet head.”

“Oh, dear, how foolish! But if you’re positive that’s it, we’ll wait a bit to see how you do. Here are two aspirin with your juice, and try to go back to sleep.” Aunt Toosie went to the window and closed the shutters. She patted my shoulder and said, “Rest now, dear,” and tiptoed out.

I had too much on my mind to rest. Besides, I was afraid that if I fell asleep, I’d forget to breathe through my mouth, so I kept myself awake thinking of the future.

“Magnificent, Dolores dearest!” cried Louis, gazing at my landscape painting and the First Place blue ribbon pinned on it. “Dolores, my darling I can’t stop thinking of you. Every moment of the day you are in my thoughts, driving me to distraction! Come away with me, my darling!”

“Oh, Louis,” I said, “you’re sweet, you really are, but I have my career to think about.”

He looked so crushed I hurried on, “But wait a bit, Louis dear, until I’ve really established myself as an artist. It won’t be long, I promise you that much.” Modestly, I refrained from listing the other prizes I’d won for my paintings, sure indications that success was near. Nor did I tell him that Leonard McClosky had also proposed and been told to wait.

I tossed my heavy black hair back and re-pinned it with the Spanish comb.

“My God, you’re beautiful!” said Louis in an awed whisper.

“Kerr-choo!” My whole head felt the explosion. I blew my nose and went to the window to breathe. I opened the shutters and tried to take a deep breath. Just as I was turning around to go back to bed, I saw the shutter in my old room open. The girl next door stood in the window, separated from me by not more than the width of a room. It was hard to tell how old she was because she was so thin. Her arms were like bones covered with skin, and her head seemed too big for her scrawny neck. Her eyes were dark and enormous; her hair was as black as Dolores del Rio’s and as curly as Sandra Lee’s. We stared so long, I had to say something. I said, “Hello!” and then, “Hello, Norma Jean.”

She smiled and her face came alive. As skinny as she was I could see she would have been pretty, a real Latin beauty, with a few—no, not a few, with many more—pounds.

“Hello, Addie,” she answered. She knew my name too!

“How did you know my name!?”

“You knew mine,” she said.

“Yes, but...” I’d forgotten how I’d learned her name, but it was in an ordinary way. Oh, yes, I remembered. The postman had told me.

“The new folks is named Valerie,” he had said. “The little gal’s name is Norma. Miss Norma Jean Valerie. Moved in from the country so the little gal can see a city doctor.”

“The postman told me your name. I have a cold and I’m supposed to spend the day in bed. Are you sick too?”

“No, I’m not sick,” was her surprising answer, “but they think so and I have to go to doctors all the time.”

What cruel parents! No wonder she was so thin. It was uncomfortable standing in the window talking loud enough to hear each other but not loud enough to be heard by Aunt Toosie and Sandra Lee.

“I used to live in your room,” I said, “and my cousin Sandra Lee lived in this one. One time when we weren’t fighting we made a telegraph wire, at least that’s what we called it, between our houses, you know. Tom showed me how.” I had forgotten she didn’t know Tom. “He lives on the other side of you,” I added.

“I know,” she said. “I saw him walking his dog this morning. He looks just like Louis.” I wondered how she knew who Louis was and was about to ask when she added, “How do you make a telegraph wire?”

“Well, that’s just a name for it, of course. It really is one big loop of string attached to each window. There’s a clothespin at one end to clip your telegraphs and letters to and when the other person pulls her end of the string, the clothespin moves across like a pulley.”

“That would be fun! Let’s do it.”

“It’ll take me a while. I’ll have to sneak out of my room to the kitchen for supplies.”

“All right,” said Norma Jean happily. “I’ll be writing a letter to you while you make the telegraph wire.” And without waiting to see what I’d answer, she left the window.

I tiptoed to my door and opened it a crack. Not a sound. Sandra Lee was in her room. I sneaked into the hall and creaked down the steps. On the tenth one, Sandra Lee said, “You’re no more sick than I am.” She was standing on the top step. When she saw my face, she added, “Your nose is red and fat! You look awful.”

“Make up your mind,” I said. “First you say I’m not sick, then you say I am.”

“I didn’t say you were sick. I said your nose looks ugly. You caught a cold last night going out on a school night, didn’t you! I’ll have to tell Mama so she’ll know what you have and what to do to make you well.”

Sandra Lee brushed past me on the steps calling, “Mama! Addie caught cold going out on a school night!” Give her rope to hang herself, I thought.

I came into the kitchen in time to hear Aunt Toosie say, “Addie told me all about it, Sandra Lee. Don’t be a tattletale.” It was a pleasure to smile sweetly at Sandra Lee.

“Hah! They’ve held ’em!” Uncle Henry’s voice came from behind the newspaper.

“Who, Daddy? Who held who?” Sandra Lee asked excitedly, forgetting about me. I could tell she thought Uncle Henry was reading about yesterday’s game and was hoping Leonard’s touchdown was mentioned.

“Whom,” I said. “Who held whom.”

“O.K., then, whom, Daddy?”

Uncle Henry lowered the newspaper and peered first at me, then at Sandra Lee. “Hitler is whom,” he said. “And the Russians are who. They’ve stopped the Huns at Moscow! Does that interest you?”

“Oh, it does me, Uncle Henry,” I lied. “What else is new?”

“Yeah, sure!” Sandra Lee said to me. “I just bet you care! So you can impress a certain older, married man with how much you know and how grown-up you are!”

“Girls!” shouted Aunt Toosie at the kitchen door. She’d caught the married man part and was looking at me in horror.

“Time to go to the office,” Uncle Henry said, stumbling out of his chair in his hurry to escape.

“Whom were you discussing?” Aunt Toosie asked, her eyes glued to me.

“I’ve been discussing foreign events with Tom and Tom’s father,” I said hurriedly, before Sandra Lee had a chance.

“Goodbye, Toosie.” Uncle Henry, hat in hand, looked in from the hall. “Sometimes, I think you girls don’t know there’s a world out there beyond Audubon Street!”

“Yes, we do, Daddy,” Sandra Lee called to his retreating back. “We talk about the war with our friends a lot.”

Sandra Lee didn’t mention that our discussions usually centered on things like how handsome some boy we knew would look in a Marine uniform.

“Then tell your friends that this country is asleep,” called Uncle Henry, “and we’re going to wake up with Hirohito in California!”

The front door slammed. Uncle Henry was like Tom and could get all worked up over the newspaper.

“Oh, look, Mama,” said Sandra Lee. “Addie’s walking barefooted with a cold!”

“Oh, Addie, darling, you shouldn’t! What do you want, dear?”

“I came to get a glass of warm water and salt to gargle with,” I said.

“Please, Addie, go back to bed. Sandra Lee will bring it up, won’t you dear?”

“No, I won’t, I’m late for school,” said Dear rudely. “It’s her own fault she’s sick and she can get her own salt water.”

“Sandra Lee! Come back here! You’re not supposed to talk to anyone like that. You…”

And while Aunt Toosie chased after Sandra Lee to the front of the house and onto the porch, I found my string, a clothespin, a heavy spoon with a hole at the top of the handle, and two oatmeal cookies. I went upstairs and glanced out the window before closing my shutters. I couldn’t see Norma Jean and I heard Aunt Toosie coming upstairs. I found my pink, rabbit-fur slippers and hurried to the bathroom. I made gargling noises and poured the hot, salt water down the washbasin.

“That’s better,” I said, coming out of the bathroom at the same time Aunt Toosie came into my room. “I think I can rest now, Aunt Toosie.”

“Good, dear. Sandra Lee apologizes. She’s very, very sorry she was rude.” Aunt Toosie went through the tucking-me-in process again. “I’ll bring you some more fruit juice later on,” she said.

As soon as she’d left I opened my shutters but there was still no sign of Norma Jean Valerie. I didn’t dare call. I spent the whole morning checking her window and plodding through a theme Sister Maurice had assigned about an imaginary conversation with God.

“Use lively dialogue,” she’d said, “and vivid description! You are there!”

I had just finished in pencil and was about to copy it in ink when Aunt Toosie came in with fruit juice and began reading aloud over my shoulder.

“‘A Celestial Conversation,’” she said, happily. “That’s a nice title.” I hate people to read my themes aloud. I slunk down under my sheets and listened to my words:

“Alone on a small cloud, I floated forward and faced God.

‘Ah-de-lade!’ said God. ‘I see by your record that you have sinned exceedingly in Thought, Word, and Deed!’

‘Oh, yes, Your Majesty,’ I answered politely. ‘I confess that I have gone and broken at least eight of the ten commandments, in fact, maybe all of them, but I’m not sure about adultery and coveting my neighbor’s wife because, you see, I am not married yet and besides I am a girl but maybe to be perfectly honest I should substitute husband and it’s true I have been noticing a certain, possibly married man, so maybe that might come under the same heading as the coveting wife or the adultery ones, it’s up to you, God, and that about covers it unless I’ve forgotten anything, and you are welcome to add it to the list!’”

Aunt Toosie’s voice was getting shaky but she continued.

“‘Ah-de-lade! Are you truly sorry for your sins?’

‘Oh, yes, Your Majesty, I am hardily sorry for having offended Thee. Through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault!’

‘All right, then, Adelaide, you’ll have to spend a short time in Purgatory, that’s a place not quite as hot as Hell, but after that you may live in Heaven with your dear mother, Darling Pasie, and your Aunt Eveline at 16B St. Peter Avenue, a very good address, with an excellent view of earth from the living room window.’

‘Oh thank you, Your Majesty!’ I said, floating happily backwards to the other clouds.

The End.”

“Addie!” Aunt Toosie moaned and sank into a chair. “You don’t believe—you don’t believe it really is… that God really is like that, do you?”

I modified my answer. “Sort of,” I said.

“Addie, God is Love!”

I said a silent prayer of thanks that Aunt Toosie did not know I knew all about real love from Dearest.

“And—and the married man?” she continued. “I hardly dare ask—but that’s just fiction, of course, isn’t it? I mean you made it up, of course?”

“Oh sure! Don’t worry about it, Aunt Toosie,” I lied. “It’s not in ink yet and I have till Monday.”

“Oh, God,” said Aunt Toosie, who never used the name of the Lord in vain. “I am going to give you catechism lessons every afternoon until we clear this up.”