Читать книгу Making Piece - Beth Howard M. - Страница 8

CHAPTER 1

ОглавлениеI killed my husband. I asked for a divorce, and seven hours before he was to sign the divorce papers, he died. It was my fault. If I hadn’t rushed him into it, I would have had time to change my mind, and I didn’t want to change my mind again. I was sure this time. I wasn’t good at being a wife and I was tired. Marcus and I still loved each other, still desired each other, we were still best friends. But in spite of best intentions, after six years, our marriage had become like overworked pie dough. It was tough, difficult to handle and the only option I could see was to throw it out and start over.

I was a free-spirited California girl, trying to mix with a workaholic German automotive executive. Too often, it had seemed like an exercise in futility, like trying to whip meringue in a greasy bowl where, with even the slightest presence of oil, turning the beaters up to a higher speed still can’t accomplish the necessary lightness of being. We needed to throw out the dough, I insisted. Chuck the egg whites, and wash out our bowls so we might fill them again. I was impatient and impulsive, overly confident that there was something, someone better out there for me. I was also mad at him. He worked too much. All I wanted was more of his time, more of him. Asking for a divorce was my cry for attention. And since I couldn’t get his attention, couldn’t get the marriage to work, couldn’t get the goddamn metaphorical pie dough to roll, I was determined to start over. It was my fault. He died because of me. I killed him.

August 19, 2009, Terlingua, Texas

I wasn’t even halfway through my morning walk with the dogs, but the sun had already risen high above the mesa of the Chisos Mountains. We should have left earlier, but every morning started with the same dilemma. Make coffee or walk the dogs first? I loved savoring my café latte on the front porch, taking that first half hour to shake off sleep and greet the day. But the window of dogwalking time was short, so the dogs always won. It never failed to amaze me how fast the sun rises in this West Texas frontier, how quickly a summer desert morning could transition from tolerable to intolerable, how a ball of fire that was welcome at first light so quickly became the enemy to be avoided, something from which to seek escape.

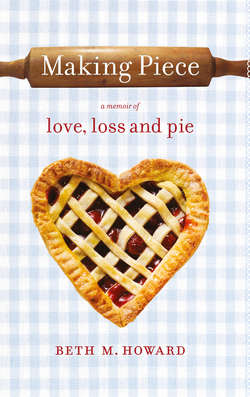

Other than the dogs’ needs, the heat made no difference to me, as I had made a commitment to staying inside no matter what the weather. My plan was to spend the summer in my rented miner’s cabin, chain myself to my computer and bang out a completed draft of my memoir about how I quit a lucrative web-producer job to become a pie baker to the stars in Malibu. How I used pies as if they were Cinderella’s slipper to find a husband, and finally did fall in love and get married, to Marcus. The book was going to be a lighthearted tale of romance, adventure and pie baking. It was supposed to have a happy ending.

As I scanned the path for rattlesnakes while Jack ran ahead on the dirt road that stretched for miles through the empty, uninhabited expanse, the only thing visible on the horizon was the heat, a thermal curtain rising up from the ground, waving like tall grass in the breeze. I looked for my second dog, Daisy, the other half of Team Terrier, as I affectionately called my four-legged companions, but her light hair was the exact blond color of the desert floor, so she was much harder to spot between the scruffy patches of sagebrush.

I had gotten into a routine of jogging in the mornings, but on this day I wasn’t feeling very strong. In fact, it wasn’t the sun baking me to a crisp or the sweat running down the back of my legs that made me want to cut the walk short. It was my heart. It was racing, even though I was walking slowly—so slowly my gait was barely a shuffle. This was not normal for me. I have the strong heart and slow pulse of a professional bike racer, so much so that I often get surprised looks from doctors when probing me with their stethoscopes.

Something was wrong with me. Was I having a heart attack? I needed to get home before I collapsed and became breakfast for the vultures who were already circling overhead. I called for my dogs, who reluctantly gave up on their bunny chase to come back to me. I looked at my digital Timex watch before I turned around. It was 8:36 a.m. Central time.

I made it back to my miner’s shack, a hundred-year-old cabin made of stacked rocks chinked with mud. It was primitive but stylish, rustic but elegant, clean and sparsely furnished with just the right touches of safari chic. Decorated by my landlord, Betty, a transplant from Austin, who lived next door, the cabin’s style was Real Simple meets Progressive Rancher. The place had running water with a basic kitchen, but the shower was in a separate wing, which could be reached only by going outside. And the toilet? The toilet was an outhouse, a twenty-five-yard walk from the house. While I loved this simple living by day, I wouldn’t go near the outhouse at night for fear of walking the gauntlet of snakes and tarantulas.

With the dogs safely back in the house—no one was going to get left outside to fry in the ungodly heat—I flopped down on my bed. My heart continued to race like a stuck accelerator, and I lay there, alone, holding my body still, thinking about how this was so unusual, so intense, so unlike any sensation I had ever experienced. I remember wondering if I was going to die. Would death come so early in my life? Really? I had just turned forty-seven, I had the heart of a bike racer, I was just out for an easy morning walk with my dogs, and now this? This was how and where it was going to end? I closed my eyes and tried to stay calm. I wasn’t afraid of death. I just didn’t think I was ready for it. Besides, if I died, who would take care of my dogs?

My BlackBerry in its rubber red casing sat next to my pillow. It rang and I glanced at the screen to see who was calling. “Unknown” was all it said. Marcus called me daily and he was the only person I knew whose number was “Unknown.” We were living apart because of his corporate job that had transferred him yet again, this time back to Stuttgart, Germany, where I had lived with him before but I’d refused to live there again. Marcus wasn’t in Germany now. He was in Portland, Oregon, taking a three-week vacation that was originally supposed to include coming to see me in Texas. But then I told him not to come. Oh, and then, after telling him not to come, I added, “As long as you’re going to be in the States, this would be a convenient time for us to get a divorce.”

I didn’t want a divorce. I just wanted him to stop working at his job so much and work more at our marriage. I wanted him to spend less energy at his office so he would have some left for me when he got home. I still loved him, we still talked every single day, and I always, always, always took his calls. Especially ever since we’d had the conversation where I let it slip that there had been a few times when I hadn’t picked up the phone when he called.

“Only when I’m writing and trying to concentrate,” I assured him. His feelings were so hurt I never had the heart to ignore a call from him again. But with my heart racing, my muscles weak and now my head aching badly, I didn’t feel up to talking to him or to anybody, so I let the call go to voice mail. It was just over two hours since I’d returned from my walk.

Twenty minutes later, I figured that if perhaps I wasn’t going to die, I should at least get my ass out of bed and go see a doctor. Terlingua, a ghost town with a population of 200, didn’t have a doctor per se, but there was a physician’s assistant at a local resort who might be able to diagnose what was wrong. Before I called him, I checked my voice mail.

The message wasn’t from Marcus.

If I could turn back the clock, if I could hit the reset button, if I could change the course of history and the unfolding of events, I would. I’d gladly sell my soul to go back in time to a date three and a half months earlier, the first week of May 2009—May 5, to be precise, our final day together—and start over from there. I was in Portland for a reunion with Marcus, who was about to begin a new one-year contract in Germany. It was the same day I got laid off from the job I had in Los Angeles, the one that I used as my excuse to leave Mexico, where Marcus had been posted for the past ten months. I had tried to be a good wife by following him to Mexico, after having followed him to Germany for almost three years and then to Portland for nearly two.

“Good wife” wasn’t a role that came naturally to me and I lasted five months with Marcus in Mexico, where I spent too many long and lonely days in our house on the pecan farm before I reached my breaking point. So I took a position as U.S. Director for a London-based speakers’ bureau, for which I would book famous people for public-speaking gigs at a rate of 120 grand for one hour of their time. The height of a tanking economy ensured I wouldn’t succeed, not when company meetings were the first budget items to get cut. No meetings, no guest speakers. Thus, six months later, the phone call from my boss in London with news of my termination came as no surprise. I’ve been fired from many jobs (let’s just say I’m a little too entrepreneurial in spirit to be employable) and I’ve never mourned the loss of anything that confined me to a cubicle in an office with sealed windows. I never looked back, because I always saw endings—fixable endings such as these, anyway—as opportunities for something new, something better. In this case, I used the free time and severance pay to travel to Texas to rent the miner’s cabin for the summer so I could write about quitting one of those cubicle-confining jobs to become a pie baker.

So during this first week of May, between the ending of Marcus’s Mexico assignment and the beginning of his new one-year contract in Germany, and coinciding with the termination of my L.A. job, we met up in Portland. Portland had been our home for almost two years, it’s where we still had a lot of friends, a houseful of furniture in storage and where his company’s North American headquarters was located. We spent four honeymoon-like days together, eating at our favorite French, Italian and Thai cafés, getting massages, drinking lattes at the hipster coffeehouses, having dinner with other couples and holding hands a lot.

We agreed we could manage the long distance with me in L.A. and him in Germany and still keep our marriage intact. We had done it before; we could do it again. We would see each other once a month and it would be a win-win, because he could continue his steady career climb, and I could avoid being a stay-at-home nag. After one year he would either find another position back in the U.S. or find a different kind of work altogether.

Our whole existence—all seven and a half years of it—was like that. It was about international airports, romantic hellos and tearful goodbyes, about job changes and job transfers. When asked what the biggest challenge of our marriage was, he would say, “Logistics.” (Though he used to say it was my lack of concern for stability, for things like health insurance and a retirement plan.) I would say the biggest obstacle was his job.

“My job provides a roof over your head,” he liked to remind me. “And health insurance.”

“I didn’t marry you so you could be my provider,” I argued. “I married you because I wanted a partner who would want to spend time together, do things together, participate in the marriage and not expect me to be the one to do all the housework while you go off to work like we’re some 1950s couple.”

“I’ll pitch in more when I’m not so busy,” he insisted. “And when you get a job.”

This made no sense to me, as there would never be an occasion when his work didn’t demand so much of his time. (In fact, it would only get worse.) And besides, as a freelancer, I wasn’t really looking for a job per se. My projects, which provided decent income, came and went, but in a “feast or famine” way—not the German way. Not the steadfast, loyal “Employee for Life” way that Germans revered.

I retaliated by applying for and getting full-time jobs. And since the only career-type work I could find was back in the U.S., I was the one being driven to the airport. This usually resulted in me getting fired and running back to my safety net, my rock, my man. I ran away, but I always came back. But once I got back, it was never long before I again faced the reality—and loneliness—of a mostly empty house and a life that was about dishes, laundry and shopping—and waiting for Marcus to come home.

His job demanded long hours, which he willingly gave, which inevitably drove me to look for something else to do. I needed to keep my brain busy, needed friends, needed to keep from getting angry with him for having moved my life halfway across the world only to feel so alone. Ironically, the only solution I could find meant living apart. It wasn’t what I wanted. I just wanted more time with him. Even if he couldn’t give me that time, I wanted him to at least acknowledge how his schedule was affecting our relationship, affecting me. I wanted him to apologize when he came home three hours later than he said he would be. Just a little “I’m sorry I was late” would have been enough. I wanted him to tell me he missed me when he was gone all day. But he said nothing. Instead, he accepted—or at least tolerated—the situation in stoic silence.

And so it went. I felt hurt, I left, I returned for happy, passion-filled reunions, the loneliness gradually set in and the cycle started all over again. It was a pattern we couldn’t seem to break.

At the end of our long weekend, Marcus drove me to the Portland airport so I could return to L.A.; he was flying to Germany the next day. I stood there in his arms, at the curbside drop-off, on a rare rainless Pacific Northwest morning, while the engine of his rented Subaru Forester idled.

Marcus’s brown hair was flattened under a tight wool cap, making his high cheekbones look even more pronounced and his almond-shaped green eyes appear even deeper. He wore a brown fleece pullover and Diesel jeans with clogs. He was secure in himself and, being European, his range of style went miles beyond an American baseball hat and sneakers. Clogs had become his signature footwear. They suited him in that ruggedly handsome way, though he could as easily transform from rugged to pure elegance and sophistication when dressed for work in his hand-tailored wool suits.

My head rested against his broad chest and I felt his breath on my neck. I breathed in his clean scent and felt his soft lips on my skin as his arms pulled me closer. “Have a safe trip, my love,” he said, in the British-German accent that I never tired of. The way he talked was so soothing, even when speaking his mother tongue, that more than once I made him read to me from a German washing-machine manual or DVD-player instruction book just to hear his sexy voice.

“And you have a safe flight to Germany,” I replied. “Let’s Skype later.” We parted with a tender kiss, our mouths touching lightly in a sort of half French kiss, until I felt self-conscious about people in the cars behind us watching and pulled away. He stayed by the car and waved until I disappeared through the revolving door. I looked back through the glass window and watched him get into his rented Subaru.

And that’s the last time I ever saw him alive.