Читать книгу Rus Like Everyone Else - Bette Adriaanse - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe sun has gone down now and is shining on the other side of the world again, but you are still here with me. We’ve seen the windows across the water switch to dark, one by one, and you can picture the inhabitants switching their lights off, making their way through the dark bedrooms, stepping barefoot into bed.

Behind a few windows the lights remain on. The secretary’s curtains light up blue; the light is coming from her laptop, which is still on. She has joined an Internet group today for people who do not like to fall asleep alone. Now she falls asleep with a Japanese girl on the laptop screen, watching her silently. The secretary named her Katie just before she fell asleep.

On the other side of the secretary’s wall, only a meter away from her head on the pillow, Mrs. Blue is sleeping too. She dreams of Grace, lying unconscious on the floor in the soap-opera mansion. Mrs. Blue turns around on her side and shakes her head in her sleep.

Down the road, on Low Street, the windows are dark as well. But on the corner there, on the ground floor of Rus’s housing block, you see a red light blink every five seconds or so. That’s the alarm on Mr. Lucas’s bedroom window; the alarm Rus hears every Monday when he sets it off to make sure that it works. Mr. Lucas is lying in his bed by the window, his face pale, his arms clenching his pillow. A chair is shoved under the door handle and he keeps a knife tucked between his mattress and the box spring, because he is afraid in the dark. He is afraid in the light too, but you will hear about that later. First, he has to get the letter that we have here for him, the letter that will change everything.

“Dear Mr. Lucas. You are invited...” it reads, and there is even a seal on the envelope, which we put neatly back on.

Rus is the only one in our neighborhood who is not sleeping. From where you are standing, right behind me, you can see his silhouette, sitting up in bed, looking at the view from his window, just like us. He could draw this view from memory: the roofs of the houses, the antennas and chimneys, the clouds passing over, all framed by the windowpane. Over the years the image has stamped itself on his brain. Never before had he considered that it could be taken from him. He has seen it for twenty-five years, every morning and evening, and it is his, his, his.

THE DEBT COLLECTORS

“Mr. Rus,” a voice said. “I know you are in there!”

Rus startled in the bed. He’d been lying with his face in the pillow, trying to forget the letter, but it remained in the middle of his thoughts, refusing to leave. And now there was a voice.

“I am here to talk about your debts,” the voice said.

“Wait,” Rus said. He got up from the bed. “Wait a second.” He quickly put on one of the tracksuits that his mother’s boyfriend had left. “Don’t go away.”

“I don’t go away,” the voice on the other side of the door said. “I am a debt collector.”

Rus zipped up the jacket and opened the door. The debt collector was a tall man in a long black jacket. He looked over Rus’s shoulder and glanced around the apartment. Then he focused his eyes on Rus.

“Mr. Rus, not only have you neglected to pay your taxes, amounting to two thousand six hundred fifteen in total, you have also ignored delayed payment fees and administration costs. In total: two thousand nine hundred eleven, to be paid to me right here, right now.”

“Yes, yes,” Rus said, raising his shoulders when he heard the number, “please don’t shout. It is in fact good that you’re here because this is a misunderstanding and it has been making me feel very restless. You can take the letter back to the tax office and tell them I cannot pay.”

“Ha ha,” the man in the jacket said, but he did not really smile. “Do you really think, Mr. Rus, that you are an exception, that you can use the facilities in this city without paying? That is stealing.”

“Don’t say stealing,” Rus said.

“Do you know what the law says about stealing? It is a crime. You are a criminal, Mr. Rus.” When the man said “mister” he squinted his eyes and spit rained on Rus’s face.

“Don’t think I don’t know your type,” the man said. “You use the roads, you use the water, and when the bills come, you pretend you don’t have any money.”

“But I don’t have money for this!” Rus said. “I don’t want this. I want to lie in my bed and I don’t want to use any facilities!”

The man raised his eyebrows and pointed at Rus’s feet. “Didn’t you get home by a government-funded road yesterday, Mr. Rus? Isn’t that a glass of water I see on your nightstand?” The collector put his foot between the door and the jamb. “Is that a real vintage tracksuit you’re wearing, Mr. Rus? Those are valuable. Where do you keep your savings? How much do you make as a controller?”

Rus pushed the door against the man’s foot. “I am not a controller,” he cried. “I am nothing. I have nothing. I just wanted to get the calculator.”

“I see. Then do I understand you have supplied the tax office with false information?” the man said, taking notes. “Do I understand you’ve consciously done so?”

“Yes,” Rus said. “You understand! It was all false and conscious! Now leave me alone!” He stepped onto the man’s foot, which he pulled back, and quickly Rus slammed the door shut.

For a few seconds nothing happened. Then Rus heard footsteps going down the stairs and it went quiet again, only the tap still dripped. Rus opened the door a few centimeters. When he didn’t see anyone, he quickly grabbed his coat and the letter and ran down the stairs.

Halfway down the staircase Rus was blocked by a man who was slamming stamps on a paper. The man was wearing a long black jacket.

“Mr. Rus?” The man looked up from the paper. “You’ve neglected to pay your tax bill, a total sum of three thousand two hundred sixty-one, which I am here to collect.”

“No, no.” Rus shook his head vigorously. “You just said two thousand nine hundred eleven.”

“I did not speak with you before, Mr. Rus,” the man said, placing his hand on Rus’s elbow. “That was another debt collector. You have recently indicated that you entered false information on your City Registration forms, which resulted in a three hundred fine for supplying false information, plus administration costs. This sum has been added to your debt. Now, where is your money?” The debt collector ran his eyes over Rus’s body.

“All I have is my mother’s old debit card,” Rus said, folding his arm across his chest. “But I need that for the Starbucks and groceries and the Wash-o-Matic.”

“Then you stop going to the Starbucks. Then you stop eating. Then you sell your kidneys. We don’t care about your life, Mr. Rus. We care about the boundaries of the law and what is possible for us within them.”

“But I need to eat,” Rus said. “I need the Starbucks.”

“A kidney does around fifteen hundred,” the debt collector said. He lowered his voice. “I could, perhaps, even introduce you to some people. A heart, of course, sells for much, much more.”

“But if I sell my heart, I die.”

“But you will have paid,” the man said. He smiled—a real smile, which grew wider and wider.

Rus stared at the man, who was now laughing with his mouth wide open. “Your tongue,” Rus said. “It’s black!”

The man stopped laughing. He covered his mouth with his papers. “It’s not,” the man said. “Do I understand you refuse to pay the amount you owe in taxes? We have the right to sell everything you own, you know.”

Rus didn’t answer. He stared at the man’s nostrils, which were also black on the inside. He took a few steps back up the stairs.

The debt collector moved up toward Rus, hiding his mouth in his collar. “We’ll take everything, Mr. Rus. Think about the kidneys.”

In one move Rus yanked his arm from the debt collector’s grip and jumped past him, down the stairs. Outside, Rus saw another man in a long coat coming toward him, carrying papers. Rus turned around and started running in the opposite direction, around the corner and over the bridge. He ran as fast as he could. For minutes and maybe even hours he ran without thinking, past the market square and the harbor, past the girls behind the windows, past the shops and the station, only listening to the sound of his feet getting him away from there.

When he finally came to a halt in a far end of the Eastern borough, he had made up his mind. With sweaty palms, he inserted his mother’s old debit card in the cash machine and pressed the button that said everything.

MR. LUCAS

“Dear Mr. Lucas. You are invited by the Queen...” For the tenth time, Mr. Lucas read the letter the post girl had delivered that morning. His heart started pounding again. “Easy,” he whispered to himself, “easy does it.” He brought the letter close to his eyes and continued. “... to stand alongside Her Majesty in the special Survivor Area of the War Memorial Service, taking place on Memorial Square, and attend the subsequent reception.”

It said that, it really said that. Mr. Lucas folded the letter and carefully placed it in the middle of his black plastic table. “To think that I, Mr. Lucas, who has achieved nothing but failure in my life, am invited to attend a ceremony where the Queen is present too!” Mr. Lucas whispered. “In less than a week from now I will be mingling with the most important people—politicians and people from television—all wearing formal dress.”

Mr. Lucas sighed. He imagined entering the reception: a solemn, sophisticated, atmosphere; women wearing long dresses, men in suits or uniforms. Maybe there would even be someone who would take his coat from him. He shivered with joy. “If only someone would take my coat!” he exclaimed. “That is my biggest dream! To just for once in my life have someone take my coat! It is a small dream, a modest dream, but if it could come true, then I would be the happiest man in the world!”

Mr. Lucas squeezed his eyes shut. “But,” he said, “it would not show. No, I would be like a true businessman. Someone who is used to having someone take his coat. Someone who would be surprised if there was no one to take his coat. ‘That Mr. Lucas,’ they will say, ‘is a true businessman.’” He started mumbling now, Mr. Lucas, as he did so often, about his dream, about being a true businessman, until the mumbling faded and he sat still with his fingers pressed against his eyelids.

“Unless,” he said, while slowly sitting up, “unless... I was a true gentleman. While all the others let the porter take their coats and let the poor man be buried in felt and fur while they chat and mingle, I will refuse! Yes, yes, that is my biggest dream, to keep someone from taking my coat, out of sheer goodness!” Mr. Lucas suddenly felt a rush of energy, the kind of rush you get when you have a truly good idea.

“My good man,” Mr. Lucas practiced, “dare you not take my coat.” Mr. Lucas turned to the other guests at the banquet. “Shan’t you be ashamed? For thy are drinking champagne while this good man needs to take coats and stand here like a weary cloth!”

Although Mr. Lucas wasn’t sure yet about the “weary cloth” part, the people at the banquet applauded him. Mr. Lucas smiled a trembling smile as he envisioned Her Majesty the Queen standing across the room, giving him a reserved but approving nod.

With that, Mr. Lucas opened his eyes on the couch. He nodded slowly. This single day with the Queen would form a counterweight to all the bad things that had ever happened to him.

ALL THE MONEY

Rus wiped the sweat from his forehead with the sleeve of his fur coat. He was sitting on a bench in Memorial Square in the business district, hidden behind the cranes and the machines that were there to build the new war monument, holding all the notes the cash machine gave him on his lap.

He was adding up the numbers on his calculator. “50,” he typed, “+ 10 + 10 + 20 + 10 + 5,” his fingers trembling. The notes he’d counted he placed on a neat pile next to him on the bench. He had to do it very carefully because his hands were shaking.

His mother had left him that debit card the day after his sixteenth birthday, the day she and Modu left him without saying anything, only leaving him a note and the card. He had never touched that debit card, aside from withdrawing a ten from it every morning of course, for groceries and things, but aside from that he never touched it.

Finally, Rus placed the last note on the pile. “There is probably a fortune on that card,” he mumbled. He had never really thought about how much money there was on the card; he had always just assumed it was there to take care of him. “Otherwise they wouldn’t have left me like that.” He closed his eyes and pressed the sum button on the calculator. Then he opened his eyes—and closed them again.

“No.”

He opened his eyes again.

“No, no.”

The reason Rus was saying “no, no” was because the number wasn’t right, it wasn’t right at all. He collected the notes and started recounting, faster this time, slamming the buttons on the calculator, adding the coins from his pocket this time as well.

Three hundred forty-one, the calculator said again, and forty-five cents.

Rus’s throat was dry. He stared at the number on the screen. “How can that be? How can that be?”

The machines on the square started slamming a pole into the ground. Deng.

The sound startled Rus, and the letter from the tax office fell off his lap, next to his trainers in the sand. The black words were staring accusingly up at him from the white paper, threatening to take his house and sell all his things. Rus swallowed. Three hundred forty-one and forty-five cents to pay three thousand two hundred sixty-one. Today.

Deng.

Rus started perspiring. The sweat on his forehead felt cold, very cold. He stood up, pressing the money to his chest, and it was as if he saw the whole world for the first time at that moment: he suddenly saw all those people walking down the streets, on their way to something, carrying bags and suitcases, talking on phones; the cars driving along the square, the trucks; the builders on the machines shouting instructions, the cranes lifting bricks.

THE SECRETARY AT WORK

The secretary was sitting behind her desk in the Overall Company offices in the business district. On her lap she held a plastic bag with a new dress for the office party. The office party would start at seven that day, and it was taking place in the office canteen. The dress she bought was sea green. She had bought it during the lunch break. She touched the fabric with her fingers. The lady at the shop said it looked stunning, and she did not look away while she said it, which meant it was true. She was a nice saleswoman, the secretary thought. She’d asked the woman if she liked swimming, but she hadn’t replied. The secretary pictured herself coming through the door at the office party, the heads of her colleagues all turning toward her as they whispered to one another: “Is that the secretary? It can’t be but it is, it is her.”

The phone rang. “Good afternoon Overall Company. I’ll put you through.” The secretary pressed the forward call button on the phone and opened her diary. It had a mirror on the inside. “Sorry, my datebook is completely full,” she said to her mirror-self. Her mirror-self did not answer. They looked at each other. The person in the mirror looked plainer and more distressed than the one in front of the mirror. It was three hours until the company party started.

It is strange, the secretary thought as she looked at the clock above the glass corridor, that the ticking of the clock doesn’t really have anything to do with time. The hands are pushed forward by batteries, not by time. Although, if time slowed down, the clocks would slow down too, of course, because time determines the speed at which everything goes forward. She studied her hands as she slowly moved them before her eyes. The people who were walking down the corridor were laughing and joking. The secretary pictured herself laughing and joking in her dress.

“She is great,” people would say to each other, and then someone would ask her to go to a restaurant and they would be inseparable ever after, and if this person had to pick one person to be on an island with, it would be her, without a doubt and the other way around.

“Yes,” the secretary said, “at first she did not know anyone, but after the office party, she was the one everybody talked about.”

THE SHOW IS OVER

“Young people don’t have respect anymore,” a man in a brown corduroy jacket said to Mrs. Blue as she rearranged her hair in the mirrored window of the supermarket. “All they do is talk on their phones. They don’t even know there was a war. They’re gonna yap all through the Memorial Service, I tell you.”

Mrs. Blue did not reply. Just because she was old didn’t mean she wanted to complain about everything. She placed her fur hat in the basket of her rolling walker and went into the store. “‘Potatoes, chocolates, lettuce, hand cream, tea, butter,’” she read out loud from her shopping list as she pushed her rolling walker through the store’s aisles.

The groceries she put in the basket, the hand cream under her fur hat.

“Nine-fifty.” The girl behind the register had a name tag that said CATHY and a gold plate on one of her teeth.

“Here you go, sweetheart,” Mrs. Blue said.

“One day there will be a virus in those mobile phones,” the man in the corduroy jacket said, standing in line behind Mrs. Blue. “It will climb into their ears and eat their brain from the inside out. Mark my words.”

“Thank you,” Mrs. Blue said. “Have a nice day.”

“We’ll see about that,” the man in the line said, and the register girl said, “Yeah,” but Mrs. Blue did not hear them, she was already rolling out of the store with her walker, back to her flat. Around the corner she took the hand cream from under the fur hat and placed it in the bag with the groceries. She pulled the hat over her ears, blocking out the noise from the kids shouting outside Hadi’s Phone Centre, and, keeping her gaze on the pavement, she pushed her rolling walker down the street to her apartment, ignoring all the traffic lights, the passersby, the drivers who shouted at her from behind the wheel when she pushed her walker in front of their cars. Mrs. Blue did not look up at anyone or anything until the doors of the elevator in her building finally closed behind her. The violin music playing in the elevator, which always seemed sad and dooming to her when she was on her way down, now sounded comforting and pleasant, like the sound of the kettle and the tune of her television show.

“I’m here, Gracie,” Mrs. Blue told the television. She had placed all the groceries in the cupboard and was now sitting on the couch, with her tea on the table and the chocolates on her lap. “You can come out.”

“Your dog needs strong bones,” the television answered. On the screen a dog was running in slow motion. It jumped through a ring. Its skeleton slowly became visible like an X-ray.

“I don’t have a dog,” Mrs. Blue said. “Thank you anyway.” She looked at the clock. Last time Rick had given Grace a horrible blow on the head. Who knew if Mario could fix his car in time to come save her.

Finally, the clock above her dining table cuckooed. Mrs. Blue sat up on the couch, humming in anticipation.

“Today we are going to talk about pregnant teenagers,” a woman on the television said. “Girls as young as twelve are having babies, some of them from men they have only met once.” People on rows of chairs in front of the woman clapped.

Mrs. Blue didn’t clap. She looked at the clock. It was three past.

“Sally is just fifteen and pregnant, but she is not sure who the father is.”

“Boo,” the people on the chairs said while Sally walked in.

“No,” Mrs. Blue said. “It’s time for Change of Hearts.”

“So what?” the pregnant girl yelled. “So what I did that?”

Mrs. Blue looked at the clock again, at the screen and back at the clock again. Then she got up to look at the bedroom clock. Three past five. “Something’s wrong,” Mrs. Blue said. “The voice is supposed to come on now and say, ‘The heart is a restless thing, where will it take us next?’” She walked up to the television and narrowed her eyes to read the channel.

“And one of the possible fathers is your mother’s ex-boyfriend!” the presenter yelled.

Mrs. Blue looked startled at the screen. A screaming woman ran onto the stage. “Beep,” she yelled.

“Oh.” Mrs. Blue took a step back and lost her balance. She tilted sideways and stumbled over the table, grabbing the tablecloth. The cup got pulled over and tea poured over the chocolates.

“You beep beep,” the woman on the TV screamed.

Mrs. Blue got hold of the remote. The tea formed a stream on the table. She switched to the other channels: cars tumbling over straw bales, someone cooking, news, news, girls in a limousine, dancing, a microscope, a building blowing up. “Grace?” Mrs. Blue asked while switching. “Grace?”

But there was no Grace. “Where is my show?” Mrs. Blue asked, but there was no one to answer her.

There was only Sally. Sally was crying. Her mascara ran down her face. She held her hand on her belly. “At least I won’t be alone anymore,” she said.

“I don’t want this.” Mrs. Blue tried to pull herself up, holding on to the table. The tea streamed from the table onto her stockings. “I want my show.”

“We’ll be right back with this double episode,” the woman said in the microphone. “Every day from five to six, instead of Change of Hearts. Don’t miss it.”

GRACE IN THE STORY

Grace was lying on the floor in the hallway of Rick’s mansion, her eyes closed, her right cheek and temple swollen and red. Rick did not hit her as hard as he could have, but hard enough for her to lose consciousness. The house was quiet, nothing moved, nothing made a sound, the clock above the front door did not even tick. There was no dust floating around in the light of the chandelier.

Then Grace’s eyelashes moved. She opened her eyes. Moaning softly, she raised her head and looked about her. She glanced at the carpet she was lying on, the walls of the hallway, the door to the stairs. Slowly she sat up against the wall and turned her face toward the dresser.

THE OFFICE PARTY

It was five past seven and the annual company party had started. The invitation said, “Ladies in dresses and men in suits, but not the other way around please!”

The secretary had made the invitations and she had also invented the joke herself. She did not know whether people had thought it was funny because the invitations were sent in the mail, so she hadn’t been there when they read it. The secretary was wearing the sea-green dress. She was not wearing a feather boa. Her boss was making a speech, standing on one of the desks.

“A great team is like a lasagne,” her boss said. “Separately, the ingredients are not very impressive, but if you put them together it can be very nice. Also, if you don’t cook the pasta, you can’t eat it at all.”

The secretary looked out the window. They were putting up fences around Memorial Square.

“I always have ketchup with my lasagne,” the secretary said to a woman standing next to her by the window. “Some people don’t like it, but I do.”

The woman pointed at her phone. “Excuse me,” she said, “I’m shopping on the Internet.”

“Yes,” the secretary said to no one in particular. “I wonder who made those nice invitations.” She walked over to the drinks section and looked at the bottles.

“That’s a wine from the south of Spain,” Fokuhama said. “Allow me.”

He poured the wine in a glass and watched her as she took a sip. “It is a decent wine,” he said, “not like a Gran Reserva Rioja from 2002 or a Barolo 2003, but it has a nice aftertaste that’s reminiscent of violas.”

The secretary swallowed the wine. “Yes,” she said. Her grandfather used to have a violin that looked a lot like a viola, but it turned out it wasn’t one. She did not want to say that. She wanted to say something sensible. “Oh, wine,” she tried. “Wine, wine.” She smiled at Fokuhama. He did not smile. She readjusted her dress. Fokuhama coughed.

“I see you are wearing a suit and not a dress,” the secretary said suddenly. She decided to wink too.

Fokuhama looked at her strangely.

“Oh,” he said. “Ah! Yes, no, not wearing a dress, no.”

The secretary said, “Ha ha,” and Fokuhama looked over his shoulder. He looks nervous, the secretary thought. She took a step toward him and lowered her voice. “Do you ever feel like you are a very interesting person on the inside, but it just doesn’t come out? That interesting things sit there inside you, waiting, but they just won’t come out?”

Fokuhama raised his eyebrows. “Hmm,” he said. “Yes, no.”

He hopped from one foot to the other. He was not very tall, Fokuhama. He said, “That is an interesting question you’ve got there.” He stood on his toes and looked over his shoulder again. “Good, good question indeed. That it does not come out but just sits there. Well, the manager is asking for me, I think. So nice to see you.”

The secretary watched Fokuhama slowly back away from her, navigating his way toward the manager’s table. She squeezed her hand around the stem of her wineglass. She felt cold.

Everywhere in the room people were talking to one another animatedly. The secretary listened with deep concentration to fragments of the conversations around her, sucking in the words: “You must give me the recipe, I love fruitcakes.” “Oh, sunsets, I can’t get enough of them, really!” “Susan is wonderful, isn’t she? A remarkable person, I do say.” “A good sunrise, on the other hand, can be nice too, don’t get me wrong.” “To meet people, to really connect with them, that is just the most precious thing for me. And family, of course.” “I’m sorry, I’m just terrible with lighters. Ha ha ha.” “Meeting people, yes, indeed, it is something else, isn’t it?”

Slowly, the secretary turned around, walked out the door quietly, through the hall and the large door, and into the cloakroom where she got her coat and where the clock said ten to eight. Just as she put on her coat she heard a voice behind her.

“Please don’t tell me you’re leaving,” a man said.

RUS NEEDS HELP

“Please,” Rus said. “I need your help.”

The checkout girl at the supermarket looked up from her register and raised her eyebrows.

“Hello,” she said. “You don’t have any groceries.”

Rus was standing exasperated in front of her register, holding the letter pressed against his chest.

“I have a letter,” Rus said. “I have to pay taxes, but all my money is gone.” When Rus heard himself say it out loud like this the horror of the situation truly dawned on him. It was as if someone were holding him by the throat.

“Oh,” the girl said. “So why are you telling me this?” She waved at the customer behind Rus to give her the groceries.

“We see each other every day, Cathy,” Rus said. “Soup, bread, lemonade. That’s me. I go to your register every day.”

“Yeah,” Cathy said. “Cathy’s not my real name. I don’t want all of East knowing my name.”

“I thought we could figure this out together,” Rus said. He placed the letter on her register. “I can’t handle it alone, you see. I have never been in this situation before. I don’t feel like myself; I can’t even think clearly.”

“So call them,” Cathy said. She pushed the letter off her register and took the groceries of the next customer from the conveyor belt. “Don’t bother me.”

“But I can’t call them. I don’t have a phone. I don’t have anything. My house is made from scrap material, and I don’t know anyone.” Rus’s voice broke.

He’d spent all afternoon pacing down the streets of the neighborhood, looking at the people in the streets and on the market square, looking for one familiar face among the people who passed him by. He had to have made at least one acquaintance during the twenty-five years he’d lived in his neighborhood, he thought; there had to be one person he’d left an impression on, one person who might want to help. But there wasn’t. Sammy from the Wash-o-Matic did not recognize him, and the people who worked at the Starbucks did not remember ever even seeing Rus, or writing his name on a cup. Rus had never really paid attention to them either; his mind was usually somewhere else—on the sea, or already busy counting the customers—so he’d never really looked at the person attached to the hand that gave him the latte.

“Please,” Rus said to Cathy, “please call them for me.”

Cathy turned her chair toward Rus. She picked up the phone by her register.

“Tell them I’ll never use the road again,” Rus suggested, but Cathy only said, “Assistance, please,” and hung up again. From the back of the store a broad-chested man in a suit came toward Rus, put his arm around him, and started pushing him toward the exit.

ALONE

From the bench on the bridge Rus watched a group of men in white gowns gathering on the corner of the street. Rus hadn’t moved since he got there, not when the sun went down behind the glass apartment buildings, nor when the streetlights went on. He did not know what to do. He was scared to go to his house because the debt collectors were waiting for him there.

The men in the white gowns greeted each other with kisses. They were laughing and wrapping their arms around one another. Rus looked up longingly as they passed him on their way to the mosque. He wanted to join them, to kiss and hug and go to the mosque too, and eat from the lamb and talk and joke and laugh so hard it would resonate between the mosaic walls.

If I were part of such a group, Rus thought, then I could tell them about the letter and they would help me and fix it for me. He imagined himself placing his letter on the dinner table, his head bent. When he looked up, he would see all the men placing money on the table, until, note by note, his burden was taken from him.

Rus looked down. In reality his burden was still there, in the shape of a white envelope, held by hands that were white from the cold. For the fifth time that day, Rus took the money out of his coat pocket and started counting again. Around him fewer and fewer cars drove down the street. The wind blew in his face, making his eyes water. Three hundred forty-one and forty-five cents, the outcome did not change.

“I don’t have anyone,” Rus said with his face buried in the fur of his coat. “I am all alone.”

At that moment, Rus felt a hand touch his shoulder. It was a strong hand, and when Rus looked up he saw a tall, dark-haired man in a fluffy coat with white feathers poking out of holes in the fabric, smiling at him.

ASHRAF AND THE STAR CEILING

Ashraf was walking home from the Eid dinner at the mosque. He was walking ahead of his family. When he was younger he had really liked the Eid celebrations, but walking home from the Eid dinner was the last thing he’d done with his father and he did not want anyone to talk to him about it. It was a very clear night and there was a star ceiling above his head. Ashraf looked up at the crescent moon and the stars. The sight reminded him of primary school, when a teacher had told them about the universe for the first time, how it had no end, how the stars they looked at were the stars from the past. It had given him a horrible bellyache, this news, and at the time he could not understand how all his classmates could be playing in the schoolyard now that they had just received this information.

Ashraf thought about how it worked the other way around too; if someone at just the right distance in the universe happened to look at this street along the canal with a gigantic telescope, they would see him and his dad walking there, as they did five years ago. He could recall the image without effort: his father walking next to him, holding his shoulder, talking slowly and pressingly.

“Don’t waste your opportunities, Ashraf. See what is out there, don’t just do anything. You have to make calculated choices.”

Ashraf searched his pocket for the key to the white van he’d bought that day. He hadn’t even told his family he’d quit his job at City Statistics yet. They’ll find out later, he thought as he looked up at the skyline of the city. The cranes that were placing the monument on Memorial Square were visible all the way from where he stood on the bridge, towering over the houses. Ashraf took a deep breath. If only tomorrow went well.

IN THE DEATH CAR

It was the lawyer who’d said “please don’t tell me you’re leaving” to the secretary. He had leaned over the cloakroom counter while he said that, smiling at her. “I wore a suit especially for you, when I much, much rather would have worn a dress, so it would be very impolite of you to go without even talking to me.”

They had been the last ones to leave the office party, after eleven. The lawyer had talked to many people and told her everybody’s name. Sometimes he’d stopped talking to wink at her. He had shown her his office, how he arranged his files, and he had grabbed her breasts from behind. He had stayed by her side all evening, not once leaving her to stand alone.

Now it was late and the secretary was sitting in the lawyer’s car. There were stars in the sky and the car was parked by a gas station that was lit up against the dark blue. There was a song on the radio that was called “In the Death Car.” The secretary watched the lawyer through the window of the gas station. He was very handsome, the lawyer; everybody in the office said so. He was ordering things and made a pistol with his fingers at the man behind the counter. The man behind the counter put his hands in the air. They both laughed.

Social skills, the secretary thought.

The lawyer got back in the car. He’d gotten her a Diet Coke. “I don’t like it when women drink regular Coke,” he said while he turned the ignition. “By the way, do you smoke?”

“I never really got around to it,” the secretary said. “But who knows.”

The lawyer laughed out loud. He brushed her cheek. “I can’t stand women who smoke, you see.”

AN ANGEL

The name of the man in the fluffy coat was Francisco. “I was just passing by the bridge in my car on my way to a meeting,” he told Rus, “and then I saw you sitting there, with your pile of money, looking so miserable, and I was overcome by a need to help.”

Francisco had immediately parked his expensive car around the corner and went over to him. He was a businessman and a humanitarian.

“I felt connected to you,” Francisco told Rus, “and it felt like a sting in my chest.” He pointed at his chest.

Rus looked up at his new friend. Francisco had the face of an angel. His eyes and eyebrows were like they were painted on with black charcoal. Yellow clouds were passing over above them, giving his hair a golden glow.

COMRADES

“Can you believe them?” Francisco called out, shaking his head. “Do you ever even use the roads?”

Francisco had taken Rus to Café Valentines on the corner of the canal so he could read Rus’s letter with the dedicated attention it deserved. He whistled between his teeth when he read the amount of taxes they were charging him.

Rus took a small sip of his drink. It was vodka. He’d never had that before, but it warmed his throat. He kept his eyes fixed on Francisco as he read the letter, his facial expression, his hands. He was also a kind of a tax expert, he’d told Rus: you have to be, when you are rich. There were many interesting similarities between Rus and Francisco: Francisco also despised debt collectors, and he also didn’t have any close friends in the city, until now. “We are comrades,” Francisco had said, and when Rus said his father was Russian Francisco had almost cried and kissed Rus on the forehead, because he too was Russian by origin.

“You don’t have to pay this.” Francisco folded the letter and put it back in the envelope. He downed his drink in one go.

“I don’t?”

“No,” Francisco said, slamming the glass on the table. “God, I needed that. And something to eat maybe.”

“I don’t have to pay it?” Rus stood up from the table. “Shouldn’t we call them? Or tell the collectors? What should we do?”

Francisco pulled Rus down to his chair.

“Easy,” he said. “It’s past ten. They’re closed now. Have a drink.”

He pressed the glass against Rus’s lips.

“We’ll go there tomorrow. Trust me.”

Rus swallowed a large gulp of the drink and looked at Francisco, his round face and sparkling eyes, the vodka still glistening on his lips, and he did trust him, completely. The warm feeling of trust spread through his chest. A feeling of dizziness also came over him in that moment; the paintings on the wall seemed to move away from him, falling to the right and back again to their old place.

Then Francisco was suddenly standing behind Rus, pulling him toward a stool at the bar. It seemed to Rus that time passed in waves all of a sudden, sometimes jolting forward and sometimes almost standing still. Also, he felt like telling Francisco things.

“My mother homeschooled me,” Rus told Francisco and the man pouring the drinks as he drank his second vodka by the bar. “She taught me everything I needed to know. All the wind directions, all the geography, the stars. We thought I was going to be a sailor, like my dad. He was helmsman on a cargo ship. But I never met him.” Rus took off his coat and stroked the fur. “All I have of him is this coat, he left it to my mother when he was shipped out, for when I was born, he said, for when I would grow up to be a sailor and it was cold at sea.”

Rus felt tears come up, and he pressed his hands against his eyes. He had never felt his sorrow in this way before: it felt pure and clear, like the vodka.

Francisco took the coat from Rus and stroked the fabric. “Why aren’t you a sailor then?”

“I practiced every day when I was little,” Rus said, “helm, ropes, right-of-way regulations, lighthouse signs.”

He looked away from Francisco and the man who poured the vodkas. “I was supposed to start at shipping school when I was sixteen. But I did not pass the exam.” He closed his eyes. “I had seasickness.”

Rus was scared to look up at his new friend after he told him this, afraid that there would be a silence like the one between him and his mother when she drove him home from shipping school in the van, back to the apartment on Low Street, where he lived with her and Modu, where they had planned to live just the two of them when Rus was off to shipping school.

Francisco stood up from his chair and took Rus’s face in his hands. “But that is beautiful, Rus,” he said, “beautiful! There is beauty in that story.”

The man behind the bar nodded.

“You try really hard to get something,” Francisco said to the bartender, “you spend your whole life working toward it, and then you fail. That is what life is about. There are no good things without the bad things, I always say. That is why people like me exist.”

“Like you?” Rus started, but Francisco pulled Rus from his stool and pressed him close against his chest, bringing his mouth to his ear.

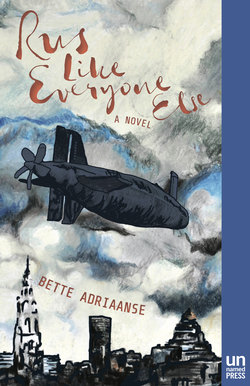

“Submarines, Rus,” he whispered. “I have an uncle in Russia who works in the navy, selling discarded submarines. They’re always looking for people to drive the submarines to the buyers. It is a job just for people like us. We will never be like everybody, Rus, no matter how hard we try, we will never fit in. We will go to Russia together. You don’t get seasick underwater, because the waves are all on the top.”

THE SECRETARY ON THE LAWYER

The secretary went home with the lawyer, who lived in West, in an apartment building with a pool. Now she was naked on top of him and held on to the edge of the headboard.

“I like to lie on my back and watch you,” he told her, “so I can see all of your bouncing beauty.” He also liked his tongue in her mouth when kissing, but not her tongue in his.

He called me a beauty, the secretary thought while sitting on top of him. She held on to her ankles and looked at her red-flushed reflection in the mirror above the bed. The lawyer had his eyes closed. With every piece of clothing he had taken off he’d looked more and more friendly to her. When finally he was sitting undressed at the foot end of the bed, his skinny body changing colors with the light of his atmosphere lamp, searching impatiently for condoms in his sock drawer, she had even found him touching.

And that is the first step of falling in love, she decided.

FRANCISCO TAKES IT ALL

Rus and Francisco stepped out of the café together. They walked under the stars in the street and Rus felt so happy; he had never felt so happy before. Francisco had taught him an old Russian song about pain and when you have it, and they had sung it over and over again in the café, with the man behind the bar as the third voice. Everything was intense and beautiful, and unfortunately Francisco had left his money in his sports car, so he paid with Rus’s money, but it was all good because he would give it back to him.

Now Rus and Francisco were on their way to Hadi’s Phone Centre to get Rus a phone, so they could call each other. The stars blinked and twinkled above them, and Rus took the letter from the tax office from his pocket and he wanted to tell Francisco how happy he was, but he did not have the words.

Suddenly they were at Hadi’s, but the lights were all off.

“Hadi,” Francisco shouted. “Hadi.”

Hadi was not there, so they banged on the door until the cleaner appeared in the window.

“I can’t sell the phones,” the cleaner said, “I’m the cleaner.” But he did let them in when Francisco explained he knew Hadi and his wife and his beautiful kids.

“Not very well though,” he explained to Rus under his breath, “not like I know you.”

Rus held on to Francisco’s shoulder as he tried to step over the threshold into the shop.

The cleaner was wearing a brown suit and white running shoes, and he showed Francisco around the store.

Rus leaned against the wall. He had never been in a mobile phone store before. It was very warm there, warm and comforting. He smiled as he watched Francisco walk around the shop, looking at the phones and trying to lift the lids off the glass boxes. His day had turned from a nightmare into a dream, and it was all because of Francisco. He raised his hand and called him, because he wanted to talk about tomorrow, about what they would do. “Francisco,” Rus said, trying to stand up from the wall, “when are we going tomorrow?” but Francisco didn’t answer, he was discussing something with the cleaner in a low voice. His voice was calming, and even though Rus couldn’t make out the words, he enjoyed listened to the cadence of it, the whispered words, and he smiled at the cleaner when he pointed at him.

Time jolted forward again, and the next moment Rus was pulled up from the wall by Francisco, who said Rus had to take off his clothes, because he’d arranged something for him.

“Why?” Rus almost fell over as he pulled the zipper of his tracksuit. “What?”

“We’ve just bought his suit,” Francisco said, pointing at the cleaner, “because it will help your case at the tax office. They don’t like tracksuits at the City Department. Lean on me.”

Leaning on Francisco with one arm, Rus stripped to his underwear in the brightly lit shop. For some reason it was hard to keep his head up, and he smiled as he looked down at Francisco helping him into the brown trousers and buttoning the brown jacket over his vest. The cleaner took Francisco’s clothes, because otherwise he’d be naked of course, Francisco explained, and Francisco took Rus’s velvet tracksuit, which was left to him by Modu when they disappeared.

“Thank you”—Rus nodded at Francisco and the cleaner as they helped him out of the shop—“thank you for everything.”

“We have to hurry a bit, Rus,” Francisco said, pushing Rus around the corner and pulling him along as they ran down the alley away from the shop. Then Rus got dizzy again, and Francisco told him to sit down for a bit.

Rus sat down and closed his eyes, and he had a very strange dream in which Francisco told him he had to leave for a bit because the plans had changed and that they would see each other in Russia by the submarines. He dreamed that Francisco folded the fur coat around him tightly, and he dreamed that he was then left alone.