Читать книгу By Faith and By Love - Beverly E. Williams - Страница 11

5

ОглавлениеCrozer Theological Seminary did accept Martin as a student. The dean offered him a scholarship and a chance to work on campus. He would need both, as his small salary had not stretched to include much in the way of savings. The Depression was causing money troubles for most people, rich and poor. Martin wrote to Mabel that he was both excited about returning to graduate school and frightened at the same time:

The Burnsville bank closed today. One of the men who lent me money to go to Louisville is a stockholder. I had been hoping I could count on him for some pennies this fall. And I must see that Mama and Pop and the boys (his two younger brothers in college) are taken care of.

The train trip to Pennsylvania was Martin’s first venture out of the South. The seminary was in Chester, near Philadelphia. As much as he wanted to follow his dream, Martin was aware how far away he was from his friend Mabel. After college she had worked for a year as teenage program director (then called “Girl Reserve Secretary”) in the Mobile, Alabama, YWCA. Because the Depression had hit everywhere, as the youngest staff member she had been laid off. Mabel had gotten a new job in Miami, Florida, in a larger YWCA with even more teenage and young adult programs under her care. Martin congratulated her, knowing that she was even farther away from Pennsylvania and worrying about how long it would be until he could see her again.

Crozer, he wrote to her that fall of 1931,

is the most stimulating place I have been since the Blue Ridge conference center where we met. The teachers are a human lot. They will work you to death, but they do all they can to bring you back to life afterward. Last Friday a group of us went to nearby Pendle Hill, a Quaker study center to hear Kagawa (a well-known Japanese pastor and writer who lived among the poor in Tokyo). He is just a regular human being, in spite of the tendency to idealize him into some kind of superman. Of course he talked about love.

Martin’s letters began to share with his friend how he felt about two big issues: war and race. Both, he believed, were addressed in Jesus’ teachings to love one’s enemies and to treat everyone with respect. He was concerned that the leadership of certain Christian student groups did not address race matters. “I want to work on that.”

He did not have to look farther than his own school to “work on it.” Martin, and several of his classmates, looked around at an all-white student body and began asking questions. If this school teaches ministers how to lead people and preach from the Bible, why are there no (Negro) students? Many of the faculty and some of their fellow students answered, “They have their own schools.” But this was not reason enough to keep doors closed to anyone who wanted to study there. The same young man who had grown up poor in mill towns of South Carolina led a student delegation to talk to the president and the trustees about opening Crozer to students of all races.

The trustees had to agree; it was difficult to call themselves Christian and deny welcome to any of God’s children. The first African American student, a young man from Virginia, would become a minister, college president and a nationally known speaker who lived until 1997, Dr. Samuel Proctor. Years later, a young man who had skipped both 9th and 12th grades and had graduated from Atlanta’s Morehouse College at the age of nineteen, studied at Crozer Seminary. Later he enrolled in Boston University and earned a doctor of philosophy degree; the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

How to live peacefully in a world gearing up for war was also on Martin’s mind. Fifty years later he could vividly recall an incident from those seminary days:

A Japanese, Naguchi, and Chinese Tsong were fellow students at Crozer in 1931. Japan had invaded China. The two students asked to speak at a seminary gathering. Each told of the suffering his family had already experienced. Both stood, took each other’s hand and pledged that their loyalty to God was higher than loyalty to a government that might send them to kill each other. They pledged to work for peace between their two countries and begged their American friends to join their efforts for peace. How well they would be able to keep their pledge, none of their friends could know. But their act laid on all who watched and heard a clear burden to affirm and support them.

Martin wrote to his mother about this experience and told her of his classes and of life outside Chester. Since Julia never had the chance to attend high school, she could not understand the names of some of his classes, much less the content. But she was proud of him going before the board of trustees and told him Jasper would have been proud of him as well. Julia was surprised that her eldest son could pass difficult courses, hold a job, and still have time to be the vice-president of the Crozer Student Association and give leadership to the local and regional chapters of the Student Volunteer Movement made up of young adult groups from various churches.

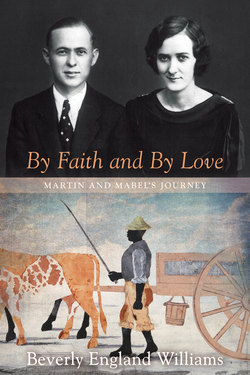

Early in December of 1931 Martin wrote to Mabel asking “for a picture if it is not too expensive, of course, to remind me every day of the girl who is coming to mean more to me than anyone else in the world. I wish that I could afford to come to see you at Christmas. Next summer is a long, long time.”

Wouldn’t it be interesting to know what Mabel wrote back? While none of her letters survive, many years later she told a friend:

When Martin and I met at the Blue Ridge conference center I realized that here was a man with visions and dreams that would take him far. He was light about it, but I could see it. As we got more serious in our friendship and our relationship he said, “Now, if you go along with me someday, no telling where we might land!”

We do know that she did send a picture, and that she saved Martin’s letters. Often if he went to a conference he would include a copy of the program, as well as a long letter about what he had heard and what he was thinking. In the days before zip codes he could address the letters: “Miss Mabel Orr, YWCA, Miami, Florida.” He would end with “Sincerely, John,” the name he was sometimes called. But Martin would forget that all the extra pages needed more postage. These letters were stamped: “Postage Due. 3 Cents.” Mabel paid, and packed the letters each time she moved, to the end of her life.

Martin wrote to her about dreams for his life’s work. Could he find a job as a minister in the South, or teach in a Southern seminary? He doubted it; his views on equal treatment of Negroes (the correct term in those days) would not be popular. He had not even been able to persuade friends at Mars Hill to have an interracial conference when the college honored the memory of “old Joe,” the slave who had been put up as collateral when the new school had run out of money. And the Depression was making it difficult for young men to be hired by small churches whose members had no jobs.

What did Mabel think of pacifism? Martin knew that being against war was a difficult position. In one of his letters he admitted, it “is the most urgent problem for Christians, now before the war machine gets propaganda better organized. We have been having some interesting discussions about that lately. One in my room until two o’clock this morning.”

For Martin, the teachings of Jesus seemed to be very clear: Love your brothers and sisters, whatever race or color, and love your enemies. Love didn’t always mean even liking them, but it meant being respectful and certainly never killing them. It also meant helping the poorest and weakest of God’s children. Martin believed that those were the people of Africa. In letters he would tell Mabel about his adventurous ideals, warning her that life with him might take her far away from Alabama and Miami: “Your work, helping young women go beyond themselves to think of others, is the most important in the country today.”

Why Africa? When Martin was old, a friend asked him that question, and it brought back a long-forgotten incident:

When I was about eight years old, my mother bought a second-hand book from a neighbor. We didn’t have money for books, and my mother was not formally educated, but she always wanted us to know about the world beyond South Carolina mill towns. The book was about Africa. It had a good thick section about President Theodore Roosevelt’s hunting expeditions in Africa. But there was also a chapter about the Christian minister, explorer and anti-slavery activist David Livingstone, and that impressed me more than anything else in the book.

Money to continue graduate school and to have a career in the 1930s was a continuing worry. Most of the regular church boards didn’t have the funds to send anybody overseas. “I will have to depend on God.” During one semester break Martin went to New York to meet with officers of a church organization: “I was ready to raise the first year’s expenses, but they want me to finish seminary and start on a doctorate. Great idea, but they can’t help me with tuition.”

He was having doubts, and they all didn’t center on money.

The other day I walked through the poorest section of Philadelphia and saw kids that were dirty, ragged, and obviously hungry. A friend who has a church in the poorest section of New York asked me why I want to go to the other side of the world when there is so much need right at home.

Martin would also write to Mabel about the classes he was taking and conferences which he and other students attended. Once they went to Washington, DC, and stayed at Howard University, a famous school for African American students, founded in 1867. “They were the nicest dorms I had ever seen!” admitting that in 1931, he had imagined the college would be poor and rundown.

Visiting cities like Philadelphia, New York, and Washington was welcome relief from studying Greek and other difficult subjects. But each time he returned to Chester, Martin struggled with where he should be: “There is so much pain in the world and I seem to be doing so little about it.”

Even going to church at Easter became a problem, as he confessed to his friend Mabel:

I didn’t feel that I cared to go when the usual foolishness is put on. I mean the fashion show. Why can’t somebody start a movement to wear the new clothes to the movies on Easter Monday and keep Sunday for worship? I decided to go to a Quaker meeting. It was one of the most helpful services I have ever attended. No music. No fuss. No lilies.

That spring, among all the serious discussions in their letters, one ended: “I love you, Martin.” Would Mabel consider coming to North Carolina that summer? Administrators at Mars Hill College had asked Martin to teach in summer school. He planned to rent a house so that his parents could escape the South Carolina heat and go to the mountains. “And for the first time in twelve years, I can live away from a dormitory!”

What happened the week that Mabel came to visit? There are, of course, no letters. There are no journals. But Martin did write after she left: “Let each of us see all the way down into the heart of the other.” And it was after that reunion he began calling her the nickname he used even when they were old:

Dear Girl, I’ve just been up on Little Mountain, trying to get my bearings. No, not just East and West, but about my work next year, and lots of other things. Does my idea of going back to school next year seem foolish to you, with no job in sight?

Martin had hoped to visit Mabel in Florida at the end of the summer, but, as usual, he had no extra money. He took one last hike along what is now the Blue Ridge Parkway, and his letter reminds the reader that hikers could once drink safely from mountain streams:

I brought pen and paper to write to you. There are ranges of mountains one after another, until they are completely lost in the blue of the sky. Cold water when you are thirsty and wondering how many miles until you find a spring. The faint chug-chug of a train in the middle of the night. Stars. Birds. Sunrise. Sunset.