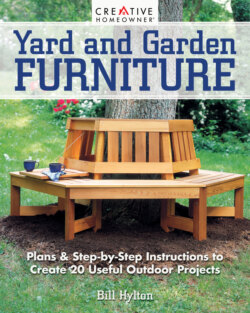

Читать книгу Yard and Garden Furniture, 2nd Edition - Bill Hylton - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Materials

ОглавлениеTables and chairs you make for your patio, deck, and yard can be just as elegant as furniture you make for your house. But outdoor furniture has to withstand exposure to the morning dew, harsh afternoon sunlight, drenching spring rains, and maybe even winter weather. For the furniture you build to survive outside, you need to use sound construction techniques and build your projects with wood, glue, and fasteners that can stand up to the weather.

WOOD

You need to work with wood that is strong, warp-free, and attractive. For these projects, the wood also has to stand up to fungi, insects, moisture, and sunlight. Some woods, such as redwood, cedar and teak, have natural characteristics that make them good candidates for outdoor furniture. But you may not be able to find them in your local lumberyard or home center, or you may find inferior grades of the wood that can make woodworking difficult.

At a typical home center, you’ll probably find that your choice of species is limited. And the wood they do have may be damp, warped, cupped, and riddled with knots. (Photo 1) You can sometimes work around knots, but the need to work exclusively with straight, flat boards is absolutely fundamental. What looked like a small bow at the lumber yard will come back to haunt you when you’re cutting joints back in the shop. Lumber that’s cupped or crooked or has any kind of twist can make a project very difficult, if not impossible to complete.

Lumber quality is a key component of any furniture project. You may be able to work around minor defects in a few boards, but it’s difficult to deal with wood with open knots, cupping, wanes, or damage along the edges.

Buy heartwood for your outdoor furniture projects. It has the more attractive color and better decay resistance. Avoid boards that are all sapwood or have a significant percentage of sapwood, like this one.

Outdoor Grades

No matter what wood you select, try to use the heartwood, which comes from the core of the tree. This wood is denser, stronger, more stable, and generally more decay-resistant than the surrounding sapwood. As its name suggests, sapwood conducts water and minerals from the roots to the leaves, so it contains a lot of moisture. Heartwood isn’t as laden with moisture, and stays remarkably stable even through large swings in humidity that affect outdoor furniture.

In the real world, many boards have both heartwood and sapwood in them, so be choosy and avoid boards that are all or mostly sapwood. (Photo 2)

If you are shopping for redwood, it’s easy to pick the heartwood because it’s specified in the redwood grading system. For example, the best grade is called Clear All Heart. It’s free of knots and is all heartwood. Clear is next best, covering boards that are free of knots but contain some sapwood.

Grading systems used for other types of lumber aren’t as forthcoming. The softwood and hardwood lumber systems use different classifications and names but grade lumber according to the volume and character of knots and blemishes. But you don’t have to pore over grading charts. Just zero in on clear stock. You’ll pay extra for a top-quality grade, but your furniture project will look better and be easier to build.

Lumber Outlets

To find the clear grades you need, you may have to call around to see who stocks, or will order premium grade lumber. This is what I did to get the lumber for the furniture projects in the book.

Several projects are made of lumber that you should be able to find locally, even in a home center. Some of the wood is stocked primarily for house framing, which means it is available in predictable thicknesses, widths, and lengths. By calling around, I found western red cedar, cypress, Douglas fir, eastern white pine, meranti, and other woods. I bought most of it from small, locally owned lumberyards that compete with the huge national chains by stocking some out-of-the-ordinary materials for decks, particularly cypress and meranti.

A committed woodworker, whether a hobbyist or a professional, might buy lumber from a specialty lumber dealer or even directly from a small local sawmill. The selection of species is likely to be broader. But you may be able to find good “outdoor ” woods such as cypress and cedar at a local outlet.

In specialty outlets, you will find native hardwoods, some of which are great outdoor woods. And you might find several imported woods, such as Honduran mahogany, teak, and ipe. This lumber will probably be drier (down to 7 or 8 percent moisture content) and more stable in your projects as a result.

You can combine different woods and finishes for striking effects.

The edges of your lumber need to be square and true, and the thickness must be uniform. If you buy rough-cut boards, you’ll need to have them dressed, or do the job yourself with a jointer and thickness-planer.

Allow your lumber to acclimate to the conditions in your shop by creating a stickered stack. Use 2x4s to keep the lumber off a concrete floor, and insert strips of wood, called stickers, between the layers.

These boards are likely stockpiled in rough-sawn condition, in what is known as random widths and lengths. The thickness is pretty consistent, and will be expressed in quarter terms. For example, a 1-inch-thick board will be listed as 4/4 and called four-quarters, and a 2-inch-thick board will be listed as 8/4 and called eight-quarters. The widths and the lengths will vary. At this kind of supply house, you will probably find prices determined by the board foot. This measurement covers length, width, and thickness. For example, one board foot is a piece of lumber that is 12 inches square and 1 inch thick. To add to the possible confusion, it’s a nominal measurement, and as the stockperson tallies up your purchase, he’ll round up.

Because this wood is rough-sawn, you will have to pay either the supplier or a local shop to dress it, or have a shop yourself that is equipped with a jointer and a thickness-planer. You need these tools to put a square and uniform edge on your lumber (Photo 3) and to make all similar lumber in a project the same thickness. If you don’t true up rough-cut lumber, you have no way of making tight joints or joining several narrow boards into a tabletop.

Lumber Storage

Allow at least a few days for your lumber to adjust to the humidity level in your shop. If you buy construction grades, they should have a moisture content no higher than 19 percent. But the lumber may be wetter or dryer than your shop and need some time to reach what’s called equilibrium moisture content. You don’t want to cut tight joints only to have them open up as the wood gives off excess moisture and twists.

For best results, stack your lumber off the floor with strips of wood between each layer to maximize air circulation. (Photo 4) Even a few days in a conditioned space can make quite a difference in wood that may have been stored under a shed roof.

Generally, low-density woods, such as cedar and redwood, have less tendency to warp, check, and change dimensions than high-density domestic woods, such as white oak and southern pine. However, some remarkably dense tropical species are quite stable.

Lumber Species

To keep the project manageable, all the material used in the furniture projects were purchased already dressed to the standard sizes. Here’s a rundown about the species I used, as well as a few you might choose.

Cypress. (Photo 5) The heartwood varies in color, but typically is a warm tan with some darker streaks. If left unfinished, it will weather to a charcoal or black color with tan highlights. This relatively lightweight wood is strong, moderately hard, and straight grained. The best grades have a smooth texture and an almost waxy feel. Flatsawn grain can be flaky and separate along the annular rings when wet, so try to buy quarter-sawn stock that has straight grain. Standard, flat-sawn lumber has end grain roughly parallel with the board face, which makes the wood more likely to cup. More-expensive quarter-sawn lumber has end grain roughly perpendicular to the board, which makes it more stable. Although cypress is resinous, it glues well, sands easily, and accepts finishes without a problem.

The lumber is sawed from the bald cypress tree, which grows in damp bottomlands along the southeastern coast and up the Mississippi basin as far as southern Illinois. It may be most available in the east and midwest.

The best stock for your outdoor furniture is, of course, the heartwood of old-growth trees. But old-growth lumber of any species is scarce. A fair amount of premium cypress is being cut from lost logs that are raised from swamp- and river-bottoms.

You may hear a variety of cypress names. Most of them stem from the color of the heartwood. White cypress is pale yellow, red cypress is reddish brown, and black cypress is dark green. Pecky cypress, prized for paneling, gets its name from a tunneling fungus that sometimes attacks older trees, creating galleries in the wood.

Douglas fir. (Photo 6) A resinous member of the pine family, and a softwood, Douglas fir (also known as Doug Fir) is relatively hard and strong. It is usually considered a construction timber, but it also serves well for furniture

The wood’s clearly delineated grain pattern alternates between light areas of soft, fine-textured wood and darker streaks of more dense grain. Flatsawn boards commonly display a cathedral-shaped figure, while quarter-sawn boards, sold as VG (for vertical grain) yield a closely spaced pinstripe pattern.

The wood can be brittle and tend to splinter, which is a common problem on decking. But if you use sharp cutters, it machines well. However, drilling pilot holes for screws is essential to avoid splitting the wood. It also glues well, and finishes easily with stains and clear finishes. You might have more trouble getting paint to adhere to it.

Cypress

Douglas Fir

Western Red Cedar

Meranti Mahogany

Pressure-Treated Southern Yellow Pine

Redwood

White Oak

Teak

Honduras Mahogany

Ipé

Western red cedar. (Photo 7) Because it is highly resistant to decay and rot, western red cedar has been used traditionally by Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest for totem poles, dugout canoes, and other outdoor applications. The wood is a dull red color when first cut, but loses most of its reddishness when exposed to the air and turns a handsome brown. The sapwood is quite white, and cedar boards may contain both sapwood and heartwood. It has a distinctive spicy odor that’s quite different from the more pleasant odor of eastern red cedar. You’ll find that prolonged or heavy exposure to the dust can be irritating.

The wood is light and very soft. Though it works easily, sharp tools are essential. It is prone to split. It is rather coarse in texture, but straight grained and very stable. Cedar is rich in tannins, so it is unwise to use any hardware containing iron.

Lumberyards typically stock common grades, but clear material seems to be readily available, though at a premium price. I used cedar for several projects, including the planter bench, the recliner, and the tree bench.

Meranti mahogany. (Photo 8) This wood is closely related to lauan (best known as a constituent of inexpensive plywood) and Philippine mahogany. Although collectively known as lauan, the meranti category is separated into white, yellow, light red, red, and dark red. The heavier dark red material has greater strength and is rated as moderately decay resistant.

Applying the name mahogany to these woods is basically a marketing gimmick. The color of the best boards resembles South American (true and genuine) mahoganies, but that’s pretty much as far as it goes. The texture is fairly coarse, the color highly variable, and the stability, which I thought was pretty good, doesn’t match that of the true mahoganies.

I have mixed feelings about the wood after using it on several of the projects. The sizing was generous. The two-by boards were really 1½ inches, as opposed to 1⅜ inches with cedar and cypress. The 5/4 meranti was 11/16 inches.

The color was highly variable, from almost burgundy to a mousy tan. I don’t know if that is a result of getting a mix of species or a mix of heartwood and sapwood. Generally, the more attractive pink-red boards were all pink-red, and the mousy boards were uniformly dull.

The grain texture is relatively coarse, even after a fair amount of sanding. When I brushed on the spar varnish finish, some areas of the wood sucked it in like a blotter. It took four coats to achieve a reasonably uniform finish.

Pressure-treated southern yellow pine. (Photo 9) This pressure-treated (PT) wood is infused with wood-preserving chemicals to resist rot and insect damage. The preservatives are forced under pressure throughout the wood, which provides more protection than surface treatments. Although some pressure-treated wood can be difficult to work (and a bit shy of standard lumber dimensions) the rot-resistance makes it very popular for decks and other outdoor applications.

Some woods, such as cedar, fit into the landscape without a finish.

The main drawback is the chemical content. Although most experts say it can’t leach out, woodworkers are warned to wear a dust mask (and safety glasses, as always) to keep from inhaling the sawdust when cutting. Also, remember that you can’t burn the scraps.

If you don’t like the green tinge of PT, you can stain it or even paint it. But it’s difficult to conceal the grain of southern yellow pine, the wood most commonly treated. (You may find other treated species, including other pines, Douglas fir, western larch, Sitka spruce, western hemlock, western red cedar, northern white cedar, and white fir.)

Pressure-treated wood is good for ground contact, but it tends to twist and warp and throw big splinters. I used it on some projects—the planter boxes that actually hold damp soil for example—but concealed the green tinge and racy grain beneath paint.

Redwood. (Photo 10) Old-growth, all-heart redwood is expensive but an ideal outdoor wood. A bright red-orange when freshly cut, it darkens to a brownish red and weathers to a silvery gray. The wood is lightweight, soft and easy to work, but very stable with a smooth texture and straight grain. And it is highly resistant to insect and fungal invasion.

Just a relatively few years ago, this wonderful old-growth redwood was readily available and inexpensive. But the supply of ancient trees has dwindled dramatically, and now most old-growth redwoods are protected from logging. As a result, interest in recycled old-growth wood is booming. Entrepreneurs are dismantling old buildings and other structures that were framed with old-growth redwood and resawing the beams into lumber.

Redwood does regenerate rapidly, but wood from second-growth trees can’t match the lumber from old-growth trees. The color is lighter, the growth rings are more widely spaced, and the wood isn’t as durable.

Nevertheless, currently available grades are still more than adequate for outdoor furniture. In fact, redwood may be your best choice for workability, good looks, and natural durability.

White oak. (Photo 11) More than 50 oak species grow in North America and are divided into two primary groups: red oak and white oak, which is stronger, harder, more durable, and better suited for outdoor furniture. White oak also is more moisture resistant than red oak.

The wood has a somewhat coarse texture to begin with. But if you plan to use spar varnish as a finish, you can smooth the texture by using wood filler, followed by a sanding sealer before varnishing. Don’t let iron hardware come in contact with white oak. Like cedar and redwood, it has a high tannin content, and iron hardware will turn the wood black.

You can find oak in some home centers nicely surfaced and sized, but only in the nominal one-by thickness. Most of the outdoor furniture projects in the book call for some 5/4 stock or some two-by stock. At a hardwoods yard, you should be able to find these other thicknesses, though in a rough-sawn state.

Teak. (Photo 12)This tropical hardwood is the ultimate in durability, stability, strength, smoothness, and ability to hold fasteners. I’ve seen rough-sawn boards at a local lumber dealer, but at $17 a board-foot, it’s out of my league. Teak is so extraordinarily expensive because unrestrained logging has made it very scarce in the wild. Fortunately, this desirable hardwood responds well to plantation management, and today most teak comes from sustainable-yield plantations in Southeast Asia and South and Central America.

Cypress makes furniture with a rich variation in the wood hues.

The heartwood, which is all that’s imported, is yellow-brown to dark brown with occasional chocolate-brown to black streaks. It is straight grained and generally easy to work. Freshly machined surfaces feel gummy because of a silica-based oil in the pores. Though the oil helps repel moisture, it can also inhibit glue adhesion, so you need to wipe joining surfaces with lacquer thinner or acetone immediately prior to applying the glue.

Honduran mahogany. (Photo 13) A fabulous wood for indoors and out, genuine mahogany has been in high demand for fine furniture since early in the eighteenth century. It is tough and highly stable, more so than any of the world’s major timbers. The grain is open, much like walnut’s, and the texture can range from fine to coarse. Its color varies: the heartwood is often yellowish when freshly cut, but soon afterward it turns reddish, pinkish, or salmon. With age, the color deepens to a rich red or brown.

Although it grows widely in the South and Central American tropics, true mahogany is becoming scarce, which is reflected in its high price. And it does seem a little frivolous to use this wonderful wood to build picnic tables. But maybe that’s just me.

Ipé. (Photo 14) This Brazilian hardwood (pronounced “ee-pay”) is another old wood that has found a new audience. Importers are promoting its use for decking, but you have little reason not to use it to make outdoor furniture. It is very similar to teak in appearance and weathering characteristics, but it is less expensive. Though heavy and extremely hard, it machines well. Like teak, it has a lot of silica in the pores, so it is hard on cutting edges.

ADHESIVES

It may be difficult to find a single type of glue that will work in every situation when building outdoor furniture. But you have a half-dozen water-resistant or waterproof glues to use. Some are packaged ready to apply, while others need to be mixed.

I used at least four types building the projects. You may opt to use exactly the same ones or choose a different type with advantages that suit your needs, such as a longer set time.

A visit to a hardware store or home center will reveal that glues rated for outdoor use are typically more expensive than general-purpose glues.

As you read labels on glue packages, you may come across water-resistance ratings of types I or II. A type I glue is rated to survive standard strength tests after repeated cycles of drying and dunking in boiling water. A type II glue is rated to resist separation after repeated wet-dry cycles in room-temperature water, but is not strength tested. Because most of the glued connections on the projects are backed up with joinery and mechanical fasteners, either type should do. Here is a brief rundown of the basic types:

Plastic resin. (Photo 15) This glue, sometimes called urea-formaldehyde glue, is highly moisture resistant and an excellent choice for outdoor projects. Open working time is a generous 20 to 30 minutes, so it’s a good choice for complex glue-up jobs. The min-imum clamping time is 12 hours. This glue produces good bond strength and good creep-resistance. In a tightly-sealed container, it also has a very long shelf life.

The glue is packaged as a powder, and you have to mix it. Once mixed, it has a pot life of four hours at 70 degrees Fahrenheit and 1½ hours at 90 degrees. But the powder contains toxins, so you need to wear a dust mask when mixing. And the mixed glue can irritate your skin, so you ought to wear protective gloves, too. After the glue has cured, it sands easily, but the dust is toxic. Another drawback is that the glue has a high minimum application temperature of 70 degrees Fahrenheit. Plastic resin glue just won’t cure in a cold shop.

Meranti is one of many tropical hardwoods used on yard furniture.

Plastic resin glue mixes up with water.

Yellow glue cleans up easily with water.

Polyurethane glue foams into gaps.

Mix epoxy glue in small batches.

Yellow glue. (Photo 16) The polyvinyl acetates (PVAs), which include the familiar white and yellow glues, are popular because they’re strong, versatile, and cheap. No mixing is required, the bottle the glue comes in usually serves as an applicator, and required clamping times are short. It also has a reasonably long shelf life.

For outdoor projects, you want Type II yellow glue, which is highly water resistant though not completely waterproof.

Like regular yellow woodworking glue, Type II yellow glue can be used at temperatures as low as 55 degrees. It sets up fast, giving you only about 5 to 10 minutes between application and clamping.

Like other yellow glues, it tends to be very “grabby, ” too. If, for example, you have to line up multiple tenons in mortises before a complex assembly can be drawn closed, you might prefer the longer open time of polyurethane glue or plastic resin glue.

Clamp the assembly at least 1 hour. As the glue cures, the glue line becomes nearly invisible.

Clean up, before the glue cures, is with water. A glue brush can be cleaned and reused many times. A wet—not just damp, but wet—rag can be used to wipe away squeeze-out before it skins over, while a chisel or scraper can do the job after that. The dried glue sands well and won’t gum up sandpaper.

After a bottle is opened, the glue has a shelf life of at least a year. It will freeze, and freezing can degrade the product.

Polyurethane. (Photo 17) This glue is versatile, strong, and reasonably convenient to use. But it has some peculiar characteristics.

It offers an unusually long open time—as much as 40 minutes according to one maker—although you may not need it because you have to apply it to only one half of a joint. But the glue needs moisture to catalyze. So unless the wood has a high moisture content—and pressure-treated wood would be in that category—you have to moisten one of the joint surfaces with a damp cloth.

Clamping time is one to four hours, depending on the ambient temperature (minimum application temperature is a fairly high 68 degrees Fahrenheit), and the glue cures fully within 24 hours. The result is a strong, creep-resistant and waterproof bond.

Remove squeeze-out by wiping the wet glue from the wood with mineral spirits or by scraping the dried glue. If you get some on your hands and don’t remove it quickly (with rubbing alcohol) you’ll carry stains for days. Note, too, that polyurethane glue presents a health hazard to asthmatics and those who tend to be highly allergic. Even if you don’t have a problem, use it with ample ventilation.

Polyurethane glue expands as it sets up. That can fill an open seam—but can also push apart joints that aren’t properly clamped. The shelf life is only two or three months.

Epoxy. (Photo 18) Epoxy is a two-part liquid system consisting of a resin and a hardener that create a solid bond. When cured, it’s an incredibly strong, gap-filling glue that is waterproof and resists creeping. The open time and the full cure time of epoxy depend on the hardener and the temperature. A fast hardener used on a hot summer day may give you a pot life of only a couple of minutes. A slow hardener used in a cold shop may allow you to work with mixed epoxy for more than an hour.

It’s so strong that you don’t need to clamp joints. In fact, you can actually weaken a joint by applying too much pressure. You can simply hold parts steady with blocks or even tape. But squeeze-out from over-clamping or using too much glue can be a nightmare.

Cured epoxy won’t come off anything very easily after it has completely dried. You can clean up squeeze-out with lacquer thinner while it is wet or scrape it off while it’s still soft. Once it hardens, you can usually get under epoxy with a chisel, but you’ll take some wood with it. You generally want to avoid skin contact with uncured epoxy and to avoid breathing dust from sanding.

OUTDOOR FASTENERS

You need corrosion-resistant fasteners to make outdoor furniture, which means screws and bolts, not nails. Consider self-drilling screws (Photo 19) that are less likely to cause splits, and star drives (Photo 20) that apply force more efficiently. Here is a brief rundown of a few of the options.

Galvanized steel. Most stock exterior-grade fasteners are galvanized. Hot-dipping is the best galvanizing method for nails, but not for screws because the process can clog the threads. Mechanically plated screws are generally suitable for decks and some furniture projects. But the iron content stains redwood and cedar. Electroplated screws have been improved with polymer coatings, but the coating is thin and can wear off even as you drive the screw.

Ceramic-coated. Ceramic-coated screws are a good alternative for woods with high tannin content such as cedar or redwood. They are typically found in green or beige.

Brass. These screws look great, and brass won’t rust, streak, or react with tannic acids the way steel does. It will eventually oxidize and turn green. The one major problem is that it’s soft. Brass screws break easily. To avoid this problem, drill a pilot hole, drive a steel screw into the hole, withdraw the steel screw and replace it with a brass one.

Silicon bronze. These screws look like brass, but the alloy won’t oxidize or corrode as easily. And they’re stronger, so they won’t strip out of a hole or snap off. But they cost about twice as much as stainless steel.

Stainless steel. These screws and bolts are the strongest and most durable on the market. While they will eventually tarnish and develop a reddish cast, they won’t stain wood or react with the tannins in redwood and cedar. They cost twice as much as coated steel.

WOOD FINISHES

Moisture, sunlight, swings in temperature, and insects can ruin your projects if you leave them unprotected. That’s where the finish comes in.

Most provide some protection from moisture, the sun, and fungi, but each finish is better at some of these jobs than at others. Frequency and ease of maintenance also vary with types of finish. Here is a look at some of the options, aside from using a rot-resistant wood with no finish and watching it weather.

Paint. Paint does the best overall job of protecting wood outdoors because it has more pigment than other finishes. Of course it also conceals the wood. But while paint provides good protection on vertical surfaces like house siding, it is usually short-lived on horizontal surfaces like tables and chair seats. And once the film is ruptured, moisture, mold, and insects can penetrate.

Self-drilling screws are less likely to splinter.

Star-drive screws (left) hold bits more securely than square- or philips drive bits.

Pigmented white shellac hides knots.

Most exterior finishes simply roll on.

If you do paint, use a good latex primer and top coat with mildewcide and fungicide additives. They are easy to apply, quick drying, and easy to clean up with water. Also use a stain killer to hide knots. (Photo 21)

Solid-color stains. Heavy-bodied stains (either latex or oil based) also conceal the wood because they have much more pigment than other stains. As a result, they form a film like paint, and the oil-based stains can even peel like paint. But because the stain is thinner than paint, the surface can be recoated many more times before it needs stripping.

Varnishes. Exterior-grade varnish has blockers instead of pigments to reduce UV damage. Marine spar varnish formulated with a tung-oil phenolic resin is made to protect boats, so it is more than adequate for furniture. But it does darken the wood.

The newer version, polyurethane spar varnish, has the flexibility and light resistance needed for exterior use, and it’s considerably less yellow than the old marine spar varnish.

Semitransparent stains. These moderately pigmented stains let some wood grain show through and still retard UV damage. They do not form a film like paint, but penetrate the surface, which keeps them from peeling.

Penetrating stains are oil-based or alkyd-based. Latex stains also are available, but they do not penetrate the wood surfaces as do the oil-based stains. Although a penetrating stain will last only a couple of years, it is easy to reapply using a roller. (Photo 22)

Water repellents. These finishes contain a small amount of wax, a resin or drying oil, a solvent, and a fungicide. Because this is only a surface treatment, the fungicide will not prevent rot, only surface mildew and fungi. The first application may be short lived.

When a discoloration appears, clean it with liquid household bleach and detergent solution; then reapply the finish. After the wood has weathered, the treatments are more enduring.