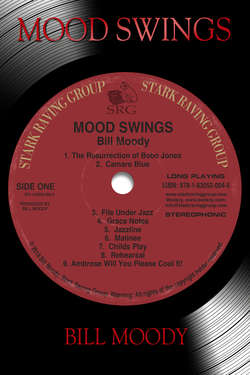

Читать книгу Mood Swings - Bill Moody - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Resurrection of Bobo Jones

ОглавлениеWhen Brew finally caught up with him, Manny Klein was inhaling spaghetti in a back booth of Chubby’s, adding to his already ample girth and plying a green-eyed blonde called Mary Ann Best with tales of his exploits as New York’s premiere talent scout. As usual, Manny was exaggerating, but probably not about Rocky King.

“The point is,” Manny said, mopping up sauce with a hunk of French bread, “this time, you’ve gone too far.” He popped the bread in his mouth, wiped his three chins with a white napkin tucked in his collar, and gazed at Brew Daniels with the incredulous stare of a small child suddenly confronted with a modern sculpture. “You’re dead, pal. Rocky’s put the word out on you. He thinks you’re crazy, and you know what? So do I.”

Mary Ann watched as Brew grinned sheepishly and shrugged. Nobody had ever called him crazy. A flake, definitely, but with jazz musicians, that comes with the territory, where eccentric behavior is a byword, the foundation of legends.

Everyone knew about Thelonious Monk keeping his piano in the kitchen and Dizzy Gillespie running for president. And who hadn’t heard about Sonny Rollins startling passersby with the wail of his mournful saxophone when he found the Williamsburg Bridge an inspiring place to play after he dropped out of the jazz wars for a couple of years.

Strange perhaps, but these things, Brew reasoned, were essentially harmless examples that merely added another layer to the jazz mystique. With Brew, however, it was another story.

Begun modestly, Brew’s escapades gradually gathered momentum and eventually exceeded even the hazy boundaries of acceptable behavior in the jazz world until they threatened to eclipse his considerable skill with a tenor saxophone. Brew had the talent. Nobody denied that. “One of jazz’s most promising newcomers,” wrote one reviewer after witnessing Brew come out on top in a duel with one of the grizzled veteran’s of the music.

It was Brew’s off stage antics – usually at the expense of his current employer – that got him in trouble, and earned him less that the customary two weeks notice, and branded him a bona fide flake. But however outlandish the prank, Brew always felt fully justified, even if his victim violently disagreed. Brew was selective, but no one, not even Brew himself, knew when or where he would be inspired to strike next. Vocalist Dana McKay, for example, never saw Brew coming until it was too late.

Miss McKay is one of those paradoxes all too common in the music business: a very big star with very little talent, although her legion of fans don’t seem to notice. Thanks to the marvels of modern recording technology, top-flight studio orchestras, and syrupy background vocals, Dana McKay sounds passable on recordings. Live is another story. She knows it, and the bands that back her up know it. When the musicians who hang out at Chubby’s heard that Brew had consented to sub for an ailing friend at the Americana Hotel, smart money said Brew wouldn’t last a week, and Dana McKay would be his latest victim. They were right on both counts.

To Brew, the music was bad enough, but what really got to him was the phony sentimentality of her act. Shaking hands with the ringsiders, telling the audience how much they meant to her exactly the same way every night — she could produce tears on cue — naturally inspired Brew.

The third night, he arrived early with a stack of McDonald’s hats and unveiled his brainstorm to the band. They didn’t need much persuading. Miss McKay had, as usual, done nothing to endear herself to the musicians. She called unnecessary rehearsals, complained to the conductor, and treated everyone as her personal slave. Except for the lady harpist, even the string section went along with Brew’s plan.

Timing was essential. On Brew’s cue, at precisely the moment Miss McKay was tugging heartstrings with a teary eyed rendition of one of her hits, the entire band donned the McDonald’s hats, stood up, arms spread majestically, and sang out, “You deserve a break today.”

Miss McKay never knew what hit her when the thunderous chorus struck. One of the straps of her gown snapped and almost exposed more of her than planned. She nearly fell off the stage. The dinner show audience howled with delight, thinking it was part of the show. It got a mention in one of the columns, but Dana McKay was not amused.

It took several minutes for the laughter to die down, and by that time, she’d regained enough composure to smile mechanically and turn to the band. “How about these guys. Aren’t they something?” Her eyes locked on Brew, grinning innocently in the middle of the sax section. She fixed him with an icy glare, and Brew was fired before the midnight show. He was never sure how she knew he was responsible, but he guessed the lady harpist had a hand in it.

Brew kept a low profile after that, basking in the glory of his most ambitious project to date. He made ends meet with a string of club dates in the Village and the occasional wedding. It wasn’t until he went on the road with Rocky King that he struck again. Everyone agreed Brew was justified this time, but for once, he picked on the wrong man.

Rocky King is arguably the most hated bandleader in America, despite his nationwide popularity. Musicians refer to him as “a legend in his own mind.” He pays only minimum scale, delights in belittling his musicians on the stand, and has been known on occasion to physically assault anyone who doesn’t measure up to his often unrealistic expectations, a man to be reckoned with. So, when the news got out, King swore a vendetta against Brew that even Manny Klein couldn’t diffuse, even though it was Manny who got Brew the gig.

“C’mon, Manny, Rocky had it coming.”

Manny shook his head. “You hear that Mary Ann? I get him the best job he’s ever had, lay my own reputation on the line, and all he can say is that Rocky had it coming. Less than a week with the band and he starts a mutiny and puts Rocky King off his own bus forty miles from Indianapolis. You know what your problem is Brew? Priorities. Your priorities are all wrong.”

Brew stifled a yawn and smiled again at Mary Ann. “Priorities?”

“Exactly. Now take Mary Ann here. Her priorities are in precisely the right place.”

Brew grinned. “They certainly are.”

Mary Ann blushed, but Brew caught a flicker of interest in her green eyes. So did Manny.

“I’m warning you, Mary Ann. This is a dangerous man, bent on self-destruction. Don’t be misled by that angelic face.” Manny took out an evil looking cigar, lit it, and puffed on it furiously until the booth was enveloped in a cloud of smoke.

“Did you really do that? Put Mr. King off his own bus?”

Brew shrugged and flicked a glance at Manny. “Not exactly the way Manny tells it. As usual, he’s left out a few minor details.” Brew leaned across the table closer to Mary Ann. “One of the trumpet players had quit, see. His wife was having a baby, and he wanted to get home in time. But kind, generous, Rocky King wouldn’t let him ride on the bus even though we had to pass right through his hometown. So, when we stopped for gas, I managed to lock Rocky in the men’s room, and told the driver that Rocky would be joining us later. It seemed like the right thing to do at the time.”

“And what has it got you?” Manny asked, emerging from the cloud of smoke, annoyed to see Mary Ann was laughing. “Nothing but your first and last check, minus of course, Rocky’s taxi fare to Indianapolis. You’re untouchable now. You’ll be lucky to get a wedding at Roseland.”

Brew shuddered. Roseland was the massive ballroom under the Musicians Union and the site of Wednesday afternoon known as cattle call. Hundreds of musicians jam the ballroom as casual contractors call for one instrument at a time. “I need a piano for Saturday night.” Fifty pianists or drummers or whatever is called for rush the stage. First one there gets the gig.

“Did the trumpet player get home in time?” Mary Ann asked.

“What? Oh, yeah. It was a boy.”

“Well, I think it was a nice thing to do.” Mary Ann leaned back and looked challengingly at Manny.

“Okay, okay,” Manny said, accepting defeat. “So, you’re the Good Samaritan, but you’re still out of work, and I…” He paused for a moment, his face creasing into a smile. “There is one thing. Naw, you wouldn’t be interested.”

“C’mon, Manny. I’m interested. Anything’s better than Roseland.”

Manny nodded. “I don’t know if it’s still going, but I hear they were looking for a tenor player at The Final Bar.”

Brew groaned and slumped back against the seat. “The Final Bar is a toilet. A lot of people don’t even know it’s still there.”

“Exactly,” said Manny. “The ideal place for you at the moment.” He blew another cloud of smoke and studied the end of his cigar. Bobo Jones is there with a trio.”

“Bobo Jones? The Bobo Jones?”

“The same, but don’t get excited. We both know Bobo hasn’t played a note worth listening to in years. A guy named Rollo runs the place. I’ll give him a call if you think you can cut it. Sorry, sport, that’s the best I can do.”

“Yeah, do that,” Brew said in a daze, but something about Manny’s smile told Brew he’d be sorry. He was vaguely aware of Mary Ann asking for directions as he made his way out of Chubby’s.

It had finally come to this. The Final Bar. He couldn’t imagine Bobo Jones there.

• • •

The winos had begun to sing.

Brew watched them from across the aisle. Two lost souls, arms draped around one another, wine dribbling down their chins as they happily crooned off key between belts from a bottle in a paper bag. Except for an immense black woman, Brew and the winos were alone as the Second Avenue subway hurtled toward the Village.

“This city ain’t fit to live in no more,” the woman shouted over the roar of the train. She had a shopping bag wedged between her knees and scowled at the winos.

Brew nodded in agreement and glanced at the ceiling where somebody had spray painted “Puerto Rico Independencia!” in jagged red letters. Priorities, Manny had said. For once, maybe he was right. Even one-nighters with Rocky King were better than the Final Bar.

The winos finally passed out after 42nd Street, but a wiry Latino kid in a leather jacket swaggered on to the car and instantly eyed Brew’s horn. Brew figured him for a terrorist or at least a mugger. It was going to be his horn or the black lady’s shopping bag.

Brew picked up his horn and hugged it protectively to his chest, then gave the kid his best glare. Even with his height, there was little about Brew to inspire fear. Shaggy blond curls over a choirboy face and deep set blue eyes didn’t worry the Puerto Rican kid, who Brew figured probably had an eleven-inch blade under his jacket.

They had a staring contest until 14th Street when Brew’s plan became clear. He waited until the last possible second, then shot off the train like a firing squad was at his back. He paused just long enough on the platform to smile at the kid staring at him through the doors as the pulled away.

“Faggot!” the kid yelled. Brew turned and sprinted up the steps, wondering why people thought it was so much fun to live in New York City.

Outside, he turned up his collar against the frosty air and plunged into the mass of humanity that often makes the city look like an evacuation. He elbowed his way across the street, splashing through gray piles of slush that clung to the curbs, soaked shoes, and provided cabbies with opportunities to practice their favorite winter pastime of splattering pedestrians. He turned off 7th Avenue, long legs eating up the slippery sidewalk, and tried again to envision Bobo Jones playing at the Final Bar, but it was impossible.

For as long as he could remember, Bobo Jones had been one of the legendary figures of jazz piano. Bud Powell, Thelonious Monk, Oscar Peterson — hell, Bobo was a jazz piano giant. But Bobo’s career, if brilliant, had also been stormy, laced with bizarre incidents, culminating one night at the Village Vanguard during a live recording session. Before a horrified opening night audience, Bobo had attacked and nearly killed his saxophone player.

Midway through the first set, the crazed Bobo had leapt wild-eyed from the piano, screamed something unintelligible, and pounced on the unsuspecting saxophonist, who thought he had at least two more choruses to play. Bobo wrestled him to the floor and all but strangled him with the microphone cord. The saxophonist was already gagging on his mouthpiece and in the end, suffered enough throat damage to cause him to switch to guitar. He eventually quit music altogether and went into business with his brother-in-law selling insurance in New Jersey.

Juice Wilson, Bobo’s two hundred and forty pound drummer, had never moved so fast in his life unless it was the time he’d mistakenly wandered into a Ku Klux Klan meeting in his native Alabama. Juice dove over the drums, sending one of his cymbals flying into a ringside table of Rotarians. He managed to pull Bobo off the gasping saxophonist with the help of two cops who hated jazz anyway. A waiter called the paramedics, and the saxophonist was given emergency treatment under the piano while the audience looked on in stunned disbelief.

One member of the audience was a photographer for Time Magazine showing his out-of-town girlfriend the sights of New York. He knew a scoop when he saw it, whipped out his camera, and snapped off a dozen quick ones while Juice and the cops tried to subdue Bobo. The following week’s issue ran a photo of Bobo, glassy-eyed, in a straitjacket, with the caption: “Is this the end of Jazz?” The two cops hoped so because they were in the photo too, and their watch commander wanted to know what the hell they were doing in a jazz club if they hadn’t busted any dopers.

The critics in the audience shook their heads and claimed they’d seen it coming for a long time as Bobo was taken away. Fans and friends alike mourned the passing of a great talent, but everyone was sure Bobo would recover. He never did.

Bobo spent three months in Bellevue, playing silent chords on the wall of his padded cell and confounding his doctors, who could find nothing wrong, so naturally, they diagnosed him as manic depressive and put Bobo back on the street. With all the other loonies in New York, one more wouldn’t make any difference.

Bobo disappeared for nearly a year after that. No one knew or cared how he survived. Most people assumed he was living on record royalties from the dozen or so albums he’d left as a legacy to his many fans. But then, he mysteriously reappeared. There were rumors of a comeback. Devoted fans sought him out in obscure clubs, patiently waiting for the old magic to return. But it seemed gone forever. Gradually, all but the most devout drifted away, until, if the cardboard sign in the window could be believed, Bobo Jones was condemned at last to the Final Bar.

Brew knew that much of the story. If he’d known the why of Bobo’s downfall, he would have gone straight back to the subway, looked up the Puerto Rican kid, and given him his horn. That would have been easier. Instead, he sidestepped a turned over garbage can and pushed through the door of the Final Bar.

A gust of warm air, reeking of stale smoke and warm beer washed over him. Dark, dirty, and foul smelling, the Final Bar is every Hollywood screenwriter’s idea of a Greenwich Village jazz club. To musicians, it means a tiny poorly lit bandstand, an ancient upright piano with broken keys, and never more than a half dozen customers if you count the bartender.

Musicians play at the Final Bar in desperation, on the way up. For Bobo Jones, and now perhaps Brew Daniels as well, the Final Bar is the last stop on the downward spiral to oblivion. But there he was, one of the true legends of jazz. One glance told Brew all he needed to know. Bobo was down, way down.

He sat slumped at the piano, head bent, nearly touching the keyboard and played like a man trying to recall how he used to sound. Lost in the past, his head would occasionally jerk up in response to some dimly remembered phrase that just as quickly snuffed out. His fingers flew over the keys frantically in pursuit of lost magic. A forgotten cigarette burned on top of the piano next to an empty glass.

To Bobo’s right were bassist Deacon Hayes and drummer Juice Wilson, implacable sentinels guarding some now forgotten treasure. They brought to mind a black Laurel and Hardy. Deacon, rail thin and solemn faced, occasionally arched an eyebrow. Juice, dwarfing his drums, stared ahead blankly and languidly stroked his cymbals. They had remained loyal to the end and this was probably it.

Brew was mesmerized by the scene. He watched and listened and slowly shook his head in disbelief. A knife of fear crept into his gut. He recognized with sudden awareness the clear, unmistakable qualities of despair and failure that hovered around the bandstand like a thick fog.

Brew wanted to run. He’d seen enough. Manny’s message was clear, but now, a wave of anger swept over him, forcing him to stay. He spun around toward the bar and saw what could only be Rollo draped over a barstool. A skinny black man in a beret, chin in hand, staring vacantly at the hapless trio.

“You Rollo? I’m Brew Daniels.” Rollo’s only response was to cross his legs. “Manny Klein call you?”

Rollo moved only his eyes, inspected Brew, found him wanting, and shifted his eyes back to the bandstand. “You the tenor player?” he asked contemptuously.

“Who were you expecting, Stan Getz?” Brew shot back. He wanted to leave, just forget the whole thing. He didn’t belong here, but he had to prove it. To Manny and to himself.

“You ain’t funny, man,” Rollo said. “Check with Juice.”

Brew nodded and turned back to the bandstand. The music had stopped, but Brew had no idea what they had played. They probably didn’t know either, he thought. What difference did it make? He tugged at Juice’s left arm that dangled near the floor.

“Okay if I play a couple?”

Juice squinted at Brew suspiciously, took in his horn case, and gave a shrug that Brew took as reluctant permission. He unzipped the leather bag and took out a gleaming tenor saxophone.

He knew why Manny had sent him down here. There was no gig. This was a lesson in humility. It would be like blowing in a graveyard. He put the horn together and blew a couple of tentative phrases. “ ‘Green Dolphin Street’ okay?”

Bobo looked up from the piano and stared at Brew like he was a bug on a windshield. “Whozat?” he asked, pointing a long slim finger. His voice was a gravelly whisper, like Louis Armstrong with a cold.

“I think he’s a sax man,” Juice replied defiantly. “He’s gonna play one.” Bobo had already lost interest.

Brew glared at Juice. He was mad now, and in a hurry. Deacon’s eyebrows arched as Brew snapped his fingers for the tempo. Then Brew was off, on the run from despair.

Knees bent, chest heaving, body rocking slightly, Brew tore into the melody and ripped it apart. The horn, jutting out of his mouth like another limb, spewed fire. Harsh abrasive tones of anger and frustration that washed over the unsuspecting patrons — there were five tonight — like napalm, grabbing them by the throat and saying, “listen to this dammit.”

At the bar, Rollo gulped and nearly fell off the stool. In spite of occasional lapses in judgment, Rollo liked to think of himself as an informed jazz critic. He’d never fully recovered from his Ornette Coleman blunder. For seventeen straight nights, he’d sat sphinx-like at the Five Spot, watching the black man with the white plastic saxophone before finally declaring, “Nothin’, baby. Ornette ain’t playing nothing.” But this time, there was no mistake. In a bursting flash of recognition, Rollo knew.

Brew had taken everybody by surprise. Deacon’s eyebrows were shooting up and down like windshield wipers on high. Juice crouched behind the drums and slashed at the cymbals like a fencer. They heard it too. They knew.

Brew played like a back up quarterback in the final two minutes of the last game of the year with his team behind seventeen to nothing. He ripped off jagged chunks of sound and slung them about the Final Bar, leaving Juice and Deacon to scurry after him in desperate pursuit. During his last scorching chorus, he pointed the bell of his horn at Bobo, prodding, challenging, until he as last backed away.

Bobo reacted like a man under siege. He’d begun as always, staring at the keyboard as if it were a giant puzzle he’d forgotten how to solve. But by Brew’s third chorus, he seized the lifeline offered and struggled to pull himself out of the past. Eyes closed, head thrown back, his fingers flew over the keys, producing a barrage of notes that nearly matched Brew’s.

Deacon and Juice exchanged glances. Where had they heard this before?

Rollo, off the stool now, rocked and grinned in pure joy. “Shee-it,” he yelled.

Bobo was back.

• • •

By the end of the first week, word had gotten around. Something was happening at the Final Bar, and people were dropping in to see if the rumors were true. Bobo Jones had climbed out of his shell and was not only playing again, but presenting a reasonable facsimile of his former talent, inspired apparently by a fiery young tenor saxophonist. It didn’t matter that Brew had been on the scene for some time. He was ironically being heralded as a new discovery. But even that didn’t bother Brew. He was relaxed.

The music and his life were, at least for the moment, under control. Mary Ann was a regular at the club — she hadn’t signed with Manny after all — and by the end of the month, they were sharing her tiny Westside apartment.

But gnawing around the edges were the strange looks Brew caught from Deacon and Juice. They’d look away quickly and mumble to themselves while Rollo showed Brew only the utmost respect. Bobo was the enigma, either remaining totally aloof or smothering Brew with attentive concern, following him around the club like a shadow. If Brew found it stifling or even creepy, he wisely wrote it off as the pianist’s awkward attempt at gratitude and reminded himself that Bobo had spent three months in a mental ward.

Of his playing, however, there was no doubt. For some unknown reason, Brew’s horn had unlocked Bobo’s past, unleashing the old magic that flew off Bobo’s fingers with nightly improvement. Brew himself was a big beneficiary of Bobo’s resurgence as his own playing reached new heights. His potential was at last being realized. He was loose, making it with a good gig, a good woman. Life had never been sweeter. Naturally, that’s when the trouble began.

He and Mary Ann were curled up watching a late movie when Brew heard the buzzer. Opening the door, Brew found Bobo standing in the hall, half hidden in a topcoat several sizes too big, and holding a stack of records under his arm.

“Got something for you to hear, man,” Bobo rasped, walking right past Brew to look for the stereo.

“Hey Bobo, you know what time it is?”

“Yeah, it’s twenty after four.” Bobo was crouched in front of the stereo, looking through the records.

Brew nodded and shut the door. “That’s what I thought you’d say.” He went into the bedroom. Mary Ann was sitting up in bed.

“Who is it?”

“Bobo,” Brew said, grabbing his robe. “He’s got some music he wants me to hear. I gotta humor him I guess.”

“Does he know what time it is?”

“Yeah, twenty after four.”

Mary Ann looked at him quizzically. “I’ll make some coffee,” she said, slipping out of bed.

Brew sighed and went back to the living room. Bobo had one of the records on the turntable and was kneeling with his head up against the speaker. Brew recognized it as one of his early recordings with a tenor player named Lee Evans, a name only vaguely familiar to Brew.

Brew studiously avoided the trap of listening to other tenor players, except maybe John Coltrane. No tenor player could avoid Coltrane, but Brew’s style and sound were forged largely on his own. A mixture of hard brittle fluidness on up tempos balanced by an effortless shifting of gears for lyrical ballads — a cross between Sonny Rollins and Stan Getz. Still, there was something familiar about this record, something he couldn’t quite place.

“I want to do this tune tonight,” Bobo said, turning his eyes to Brew. It was the first time Bobo had made any direct reference to the music since they’d started playing together.

Brew nodded, absorbed in the music. What was it? He focused on the tenor player and only vaguely remembered coming in with coffee. Much later, the record was still playing and Mary Ann was curled up in a ball on the couch. Early morning sun streamed in the window. Bobo was gone.

“You know it’s funny,” Brew told Mary Ann later. “I kind of sound like that tenor player Lee Evans.”

“What happened to him?”

“I don’t know. He played with Bobo quite a while, but I think he was killed in a car accident. I’ll ask Rollo. Maybe he knows.”

But if Rollo knew, he wasn’t saying. Neither were Juice or Deacon. Brew avoided asking Bobo, sensing it was somehow a taboo subject, but it was clear they all knew something he didn’t. It became an obsession for Brew to find out what.

He nearly wore out the records Bobo had left, and unconsciously, more and more of Lee Evans’ style crept into his own playing. It seemed to please Bobo and brought approving nods from Juice and Deacon. As far as Brew could remember, he had never heard of Lee Evans until the night Bobo had brought him the records. Finally, he could stand it no longer and pressed Rollo. He had to know.

“Man, why you wanna mess things up for now?” Rollo asked, avoiding Brew’s eyes. “Bobo’s playin’, the club’s busy, and you gettin’ famous.”

“C’mon, Rollo. I only asked about Lee Evans. What’s the big secret?” Brew was puzzled by the normally docile Rollo’s outburst and intrigued even more. However tenuous Bobo’s return to reality, Brew couldn’t see the connection. Not yet.

“Aw shit,” Rollo said, slamming down a bar rag. “You best see Razor.”

“Who the hell is Razor?”

“One of the players, man. Got hisself some ladies, and he’s…well, you talk to him if you want.

“I want,” Brew said, more puzzled than ever.

Mary Ann was not so sure. “You may not like what you find,” she warned. Her words were like a prophecy.

• • •

Brew found Razor off 10th Avenue.

A massive maroon Buick idled at the curb. Nearby, Razor, in an ankle length fur coat and matching hat, peered at one of his “ladies” from behind dark glasses. But what really got Brew’s attention was the dog. Sitting majestically at Razor’s heel, sinewy neck encased in a silver stud collar, was the biggest, most vicious looking Doberman Brew had ever seen. About then, Brew wanted to forget the whole thing, but he was frozen to the spot as Razor’s dog — he hoped it was Razor’s dog — bared his teeth, growled throatily, and locked his dark eyes on Brew.

Razor’s lady, in white plastic boots, miniskirt, and a pink ski jacket, cowered against a building. Tears streamed down her face, smearing garish makeup. Her eyes were riveted on the black man as he fondled a pearl-handled straight razor.

“Lookee here, mama, you makin’ ole Razor mad with all this talk about you leavin’, and you know what happens when Razor get mad, right?”

The girl nodded slowly as he opened and closed the razor several times before finally dropping it in his pocket. “All right then,” Razor said. “Git on outta here.” The girl glanced briefly at Brew and then scurried away.

“Whatcha you look at, honky?” Razor asked, turning his attention to Brew. Several people passed by them, looking straight ahead as if they didn’t exist.

Brew’s throat was dry. He could hardly get the words out. “Ah, I’m Brew Daniels. I play with Bobo at the Final Bar. Rollo said—”

Bobo? Shee-it.” Razor slapped his leg and laughed, throwing his head back. “Yeah, I hear that sucker’s playing again.” He took off his glasses and studied Brew closely. “And you the cat that jarred them old bones? Man, you don’t even look like a musician.”

The Doberman cocked his head and looked at Razor as if that might be a signal to eat Brew. “Be cool, Honey,” Razor said, stroking the big dog’s sleek head. “Well you must play, man. C’mon, it’s gettin’ cold talkin’ to these bitches out here. I know what you want.” He opened the door of the Buick. “C’mon, honey, we goin’ for a ride.”

Brew sat rigidly in he front seat trying to decide who scared him more, Razor or the dog. He could feel Honey’s warm breath on the back of his neck. “Nice dog you have, Mr. Razor.” Honey only growled. Razor didn’t speak until they pulled up near Riverside Park.

He threw open the door, and Honey scrambled out. “Go on, Honey, git one of them suckers.” Honey barked and bounded away in pursuit of a pair of unsuspecting Cocker Spaniels.

Razor took out cigarettes from a platinum case, lit two with a gold lighter, and handed one to Brew. “It was about three years ago,” Razor began. “Bobo was hot, and he had this bad-assed tenor player called Lee Evans. They was really tight. Lee was just a kid, but Bobo took care of him like he was his daddy. Anyway, they was giggin’ in Detroit or someplace, just before they was spozed to open here. But Lee, man, he had him some action that he wanted to check out on the way, so he drove on alone. He got loaded at this chick’s pad, then tried to drive all night to make the gig.” Razor took a deep drag on his cigarette. “Went to sleep. His car went right off the pike into a gas station. Boom! That was it.”

Razor fell silent. Brew swallowed as the pieces began to fall into place.

“Well, they didn’t tell Bobo what happened till an hour before the gig, and them jive-ass dumb record dudes said, seein’ how they’d already given Bobo front money, he had to do the session. They got another dude on tenor. He was bad, but he wasn’t Lee Evans. At first, Bobo was cool, like he didn’t know what was happening. Then, all of a sudden, he jumped on this cat, scared his ass good, screaming, ‘you ain’t Lee, you ain’t Lee.’ “ Razor shook his head and flipped his cigarette out the window.

Brew closed his eyes. It was so quiet in the car that Brew was sure he could hear his own heart beating as everything came together. All the pieces fell into place except one, but he had to ask. “What’s this all got to do with me?”

Razor turned to him, puzzled. “Man, you is one dumb honky. Don’t you see, man? To Bobo, you is Lee Evans all over again. Must be how you blow.”

“But I’m not,” Brew protested, feeling panic rise in him. “Somebody’s got to tell him I’m not Lee Evans.”

Razor’s eyes narrowed; his voice lowered menacingly. “Ain’t nobody got to tell nobody shit. Bobo was sick for a long time. If he’s playin’ again cause of you, that’s enough. You,” he pointed a finger at Brew, “jus’ be cool and blow your horn.” There was no mistake. It was an order.

“But…”

“But nothin’. If there’s anything else goin’ down, I’ll hear about it. Who do you think took care of Bobo? You know my name, man? Jones. Razor Jones.” He smiled at Brew suddenly, seeing that Brew failed to make the connection. “Bobo’s my brother.”

Razor started the car and whistled for Honey. Brew got out slowly and stood at the curb like a survivor of the holocaust. The huge Doberman galloped back obediently, sniffed at Brew, and jumped in next to Razor.

“Bye,” Razor called, flashing Brew a toothy smile. Brew could swear Honey sneered at him as the car pulled away.

• • •

The Final Bar was now the in place in the Village. Manny had seen to that, forgiving Brew for all his past sins and recognizing Bobo’s return, if artfully managed, would insure all their futures. If anything, Manny was pragmatic. He was on the phone daily, negotiating with record companies and spreading the word that a great event in jazz was about to take place.

Driven by the memory of Razor’s menacing smile, Brew played like a man possessed, astonishing musicians who came in to hear for themselves. He was getting calls from people he’d never heard of, offering record dates, road tours, even to form his own group. But of course, Brew wasn’t going anywhere. He was miserable.

“You were great, kid,” Manny said, looking around the club. It was packed every night now, and Rollo had hired extra help to handle the increase in business. “Listen, wait till you hear the deal I’ve made with Newport records. A live session, right here. The return of Bobo Jones. Of course, I insisted on top billing for you, too.” Manny was beaming. “How about that, eh?”

“I think I’ll go to Paris,” Brew said, staring vacantly.

“Paris?” Manny turned to Mary Ann. “What’s he talking about?”

Mary Ann shrugged. “He’s got this crazy idea about Bobo.

“What idea, Brew? Talk to me.”

“I mean,” Brew said evenly, “there isn’t going to be any recording session, not with me anyway.”

Manny’s face fell. “No recording? Whatta you mean? An album with Bobo will make you. At the risk of sounding like an agent, this is your big break.”

“Manny, you don’t understand. Bob thinks I’m Lee Evans. Don’t you see?”

“No, I don’t see,” Manny said glaring at Brew. “I don’t care if he thinks you’re Jesus Christ with a saxophone. We’re talking major bucks here. Big. You blow this one and you might as well sell your horn.” Manny turned back to Mary Ann. “For God’s sake, talk some sense into him.”

Mary Ann shrugged. “He’s afraid Bobo will flip out again, and he’s worried about Bobo’s brother.”

“Yeah, Manny, you would be too if you saw him. He’s got the biggest razor I’ve ever seen. And if that isn’t enough, he’s got a killer dog that would just love to tear me to pieces.”

“What did you do to him? You’re not up to your old tricks again are you?”

No, no, nothing. He just told me, ordered me, to keep playing with Bobo.

“So, what’s the problem?”

Brew sighed. “For one thing, I don’t like being a ghost. And what if Bobo attacks me like the last time. He almost killed that guy. Bobo needs to be told, but no one will do it, and I can’t do it. So, it’s Bobo, Razor, or Paris. I’ll take Paris. I heard there’s a good jazz scene there.”

Manny stared dumbly at Mary Ann. “Is he serious? C’mon, Brew, that’s ridiculous. Look, Newport wants to set this up for next Monday night, and I’m warning you, screw this up, and I will personally see that you never work again.” He laughed and slapped Brew on the back. “Trust me, Brew. It’ll be fine.”

• • •

But Brew didn’t trust anyone, and no one could convince him. Even Mary Ann couldn’t get through to him. Finally, he decided to get some expert advice. He checked with Bellevue but was told that the case couldn’t be discussed unless he was a relative. He even tracked down the saxophonist Bobo had attacked, but as soon as he mentioned Bobo’s name, the guy slammed down the phone.

In desperation, Brew remembered a guy he’d met at one of the clubs. A jazz buff, Ted Fisher was doing his internship in psychiatry at Columbia Medical School. Musicians called him Doctor Deep. Brew telephoned him, explained what he wanted, and they agreed to meet at Chubby’s

“What is this, a gay bar?” Ted Fisher asked, looking around the crowded bar.

“No, Ted, there just aren’t a lot of lady musicians. Now look I—”

“Hey, isn’t that Gerry Mulligan over there at the bar?”

“Ted, c’mon. This is serious.”

“Sorry, Brew. Well, from what you’ve told me already, as I understand it, your concern is that Bobo thinks you’re his former saxophonist, right?”

Brew looked desperate. “I don’t think it, I know it. Look, Bobo attacked the substitute horn player. What I want to know is what happens if the same conditions are repeated. Bobo is convinced I’m Lee Evans now, but what if the live recording session triggers his memory and brings it all back and he suddenly realizes I’m not? Could he flip out again and go for me?” Brew sat back and rubbed his throat.

“Hummm,” Ted murmured and gazed at the ceiling. “No, I wouldn’t think so. Bobo’s fixation, brought about by the loss of a close friend, whom he’d actually, though inadvertently, assumed a father figure role for, is understandable and quite plausible. As for a repeated occurrence, even in simulated identical circumstances, well-delayed shock would account for the first instance, but no, I don’t think it’s within the realm of possibility.” Ted smiled at Brew reassuringly and lit his pipe.

“Could you put that in a little plainer terms?”

“No, I don’t think it would happen again.”

“You’re sure?” Brew was already feeling better.

“Yes, absolutely. Unless…”

Brew’s head snapped up. “Unless what?”

“Unless this Bobo fellow suddenly decided he…he didn’t like the way you played. Brew? You okay? You look a little pale.”

Brew leaned forward on the table and covered his face with his hands. “Thanks, Ted,” he whispered.

Ted smiled. “Anytime, Brew. Don’t mention it. Hey, do you think Gerry Mulligan would mind if I asked him for his autograph?”

• • •

In the end, Brew finally decided to do the session. It wasn’t Manny’s threats or insistence. They had paled in comparison to Razor. It wasn’t even Mary Ann’s reasoning. She was convinced Bobo was totally insane. No, in the end, it was the dreams that did it. Always the dreams.

A giant Doberman, wearing sunglasses and carrying a straight razor in its mouth was chasing Brew through Central Park. In the distance, Razor stood holding Brew’s horn and laughing. Brew had little choice.

On one point, however, Brew stood firm. The Newport Record executives had taken one look at the Final Bar and almost cancelled the whole deal. They wanted to move the session to the Village Vanguard, but Brew figured that was tempting fate too much. Through Mary Ann, Bobo had deferred the final decision to Brew, and as far as he was concerned, it was the Final Bar or nothing. The Newport people eventually conceded and set about refurbishing the broken down club. Brew had to admit, they had really spent some money. The club was completely transformed, with repainting, new tables and chairs, blow up photos of jazz greats on the walls, and the sawdust floors replaced with new carpeting.

When Brew and Mary Ann arrived, Rollo, nattily attired in a tuxedo, collecting hefty admission charges and looking as smart as any midtown maitre d’, greeted them at the door.

“My man, Brew,” he smiled, slapping Brew’s palm. “Tonight’s the night.”

“Yeah, tonight’s the night,” Brew mumbled as they pushed through the crowd of fans, reporters, and photographers. Manny waved to them from the bar where he was huddled with the Newport people. A Steinway grand had replaced the battered upright piano, and a tuner was making final adjustments as engineers scurried about running cables and testing microphones.

Brew suddenly felt a tug at his sleeve. He turned to see Razor, resplendent in a yellow velvet suit, sitting with a matching pair of leggy blond girls. Honey hovered nearby. Razor flashed a smile at Mary Ann and nodded to Brew. “I see you been keepin’ cool. This your lady?”

Brew stepped around Honey, wondering if it were true that dogs can smell fear. “Yeah. Mary Ann, this is Razor.”

Razor stood and bowed deeply and kissed Mary Ann’s hand, then stepped back. “Say hello to Sandra and Shana.”

“Hi,” the girls chorused in unison.

“What are you doing here?” Brew asked Razor.

“What am I doin’ here? Man, this is my club. Didn’t you know that?” He flashed Brew another big grin. “You play good now.”

In a daze, Brew found Mary Ann a seat near the bandstand. As the piano tuner finished, a tall man in glasses and a three-piece suit walked to the microphone and introduced himself as Vice President of Newport Records. He called for quiet, perhaps the first time it had ever been necessary at the Final Bar.

“Ladies and Gentlemen, as you all know, we are recording live here tonight, so we’d appreciate you cooperation. Right now though, let’s give a great big welcome to truly one of the giants of jazz, Mr. Bobo Jones and his quartet.”

The applause was warm and real as the four musicians took the stand. Bobo, Deacon, and Juice were immaculate in matching tuxes. Brew dressed likewise but at the last minute, elected to opt for a white turtleneck sweater. Bobo bowed shyly as the crowd settled down in anticipation.

Brew busied himself with changing the reed on his horn and tried to blot out the image of Bobo leaping from the piano, but there was nowhere to go. He rubbed his throat and tried to smile at Mary Ann as the sound check was completed. It was time.