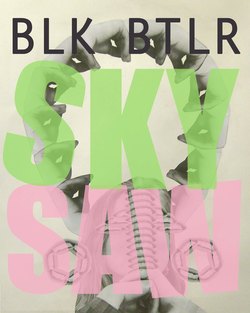

Читать книгу Sky Saw - Blake Butler - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPerson 1180 watched the baby on the table rasping and gabbing at itself. She measured the stutter of the indention in the child’s cranium, which by now should have sealed. In the slick inch-width porthole for the child’s skull, 1180 sometimes saw things crawl in or out. Sometimes she’d put her eye to the knot and peer in. She saw nothing. She’d been squirted in the face. She kissed the hole and she wished into it. The children was growing faster than he should be, she thought: this other little man. She should not be able to distinguish hour to hour how he’d changed, the shape of his infancy already leaving his skin behind for other colors.

The mother had a resume of rancid husbands since her husband’s exit, a list she kept lodged in her chest, each one that much ouched over the other, aching one another out inside the nights of screeching and endless bleeding, burned from white to orange to red to brown to black to gold inside her mind. She could not recall any of these men’s numbers, nor the specific texture of their hands, though they were in her, all compounded and compounding. Each day the list grew longer one by one or two or ten. Each one she’d shown a new part of herself that they could take away and keep and keep inside them, or perhaps hang upon some wall, or maybe eat or smudge or overpower, somehow rip unto destroyed.

The child, not yet a man himself, seemed somehow smearing in the absence of the father. His waking flesh was mostly gray. His thumbprints had the grain of gravel and against certain kinds of wood would give off sparks. The last time the mother had weighed the child the scale displayed all numerals she could not read.

The child’s veins would sometimes bloat and stiffen. He already had acquired all his teeth, more teeth than he should ever have at all, together. Every morning 1180 shaved a brand new mustache off her child’s top lip with the electric razor the father had left behind. He had taken the straight-edged other with him, perhaps a weapon—as well, he’d taken his legs and arms that 1180 had used to calm herself and spread herself and remember at all she was there, though he’d left the locking necklace he’d given her with her photo pasted inside. Sometimes now she would open up the necklace and see not herself but blackened paper, sometimes a tiny wedge of mirror, a scratch n sniff of stew.

Most evenings now 1180 slept with the child beside her in the night, along with the child’s dolls and caps and all his clothes, each of which she’d fashioned from the crap that fell into the house among its yawnings, junk blown from the remains of other houses and small polished portions of the sky—this way gathered all together there’d be sufficient mass upon the bed to bruise in the mother an illusion as if there were still someone there beside.

Someone is there, she would say aloud inside herself repeating. This child. My child. My son. Person two-thou-sand-and-thir-ty, my nearest number.

The mother felt the creaming liquid in her whorl.

The men were coming up the stairs. The men were chanting.

The men were made of meat.