Читать книгу The First America's Team - Bob Berghaus - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

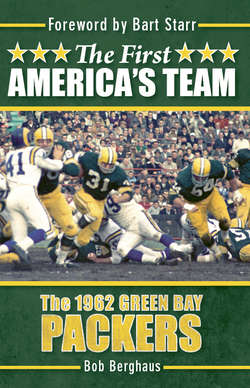

CHAPTER 1 Football as It Should Be Played

Оглавление“Football is two things. It’s blocking and tackling. You block and tackle better than the team you’re playing, you win.”

That was the mindset of Vince Lombardi, who in 1962 was the most famous football coach of what was probably the most revered professional football team in America. During that season, his Green Bay Packers blocked and tackled better than the other thirteen teams in the National Football League. They led the league in scoring with 415 points, and the 148 points given up by Green Bay’s hard-hitting defense was the fewest in the league.

Those totals, by the way, were also better than all eight teams in the rival American Football League, which was in its third year of existence. The Packers’ winning margin of 19.1 per game was more than 10 points better than all other team in the NFL.

Four years earlier, the Packers were at rock bottom following a 1–10–1 record. Ray “Scooter” McLean, a nice man who didn’t understand the meaning of discipline, quit before he would have been dismissed as coach. In the winter of 1959 the Packers hired Lombardi, who had been offensive coordinator for the New York Giants since 1954.

Lombardi was a tough-as-nails guard at Fordham, playing on the legendary “Seven Blocks of Granite” offensive line. After college he became a high school teacher and coach. He returned to Fordham to coach the freshman football team, and then moved on to West Point as an assistant to the legendary Red Blaik. With the Giants, Lombardi became known in NFL circles as a top-flight coordinator, but when head coaching jobs came up he was passed over until he finally got his chance with the Packers at age forty-five.

The Packers won their first three games under Lombardi before losing five in a row to end any hopes of a dramatic worst-to-first turnaround. Struggling at 3–5, the Packers seemed destined to have another losing season. Remarkably, they turned around during the last third of the season, winning their final four games for a 7–5 record and their first winning season in twelve years.

During those four games the Packers outscored their opponents 119–51, scoring almost as many points as the 129 totaled during the first eight games. The defense, by giving up an average of just under 13 points in those final four games, also showed remarkable improvement after allowing an average of 31.8 points per game during the losing streak.

The Packers entered 1960 with thoughts of achieving more than a winning record. They had talent up and down the roster with most of the starters in their mid-twenties. Green Bay won all five of its exhibition games and appeared to have momentum going into the season opener against the Chicago Bears.

Instead, they lost at home to the team coached by legendary George Halas, but then reeled off four straight wins, putting themselves in position to unseat the Baltimore Colts, who had won the last two NFL titles, as champions of the Western Division.

That goal wasn’t going to come easily. The Packers won just once during their next four games, falling to 5–4 following a 23–10 loss to the Lions in the traditional Thanksgiving Day game in Detroit, when the Packers looked flat on offense, totaling just 181 yards.

The fortunes of the Green Bay Packers changed dramatically when Vince Lombardi took the head-coaching job.

They were still in the title race but likely needed to sweep the final three games. Ten days after the loss to Detroit they traveled to Chicago for a rematch with the Bears and beat their archrivals by 28 points, setting up a first-place showdown with the San Francisco 49ers, who, like Green Bay, had a 6–4 record. The Colts also were 6–4, but that day they dropped a game back after losing to the Rams. In San Francisco, the Packers defense pitched a shutout, fullback Jim Taylor rushed for 161 yards, and halfback Paul Hornung provided all the scoring in a 13–0 win.

The following week the Packers closed out the season with a 35–21 win in Los Angeles against the Rams. Quarterback Bart Starr completed touchdown passes of 91 yards to Boyd Dowler and 57 yards to Max McGee. The win put the Packers in the championship game for the first time since 1944.

They faced the Philadelphia Eagles, trying to win their first title since 1949. The Packers had a 13–10 lead early in the fourth quarter but a long kickoff return by Ted Dean set up a winning touchdown, and the Packers lost 17–13. After that defeat, Lombardi told his players they’d never lose another championship game.

The title game appearance in 1960 wasn’t a fluke. The next year, Green Bay cruised to the Western Conference title and hosted the Giants in the 1961 championship game at City Stadium. Lombardi was fond of the Mara family, which owned the Giants. He had attended Fordham University with Wellington, the son of Tim, who founded the Giants in 1925.

When it came time for the game on December 31, Lombardi forgot about friendship for an afternoon. After a scoreless first quarter, his Packers blocked and tackled considerably better than the big-city team, scoring 24 points in the second quarter on the way to a 37–0 victory. It could have been worse—much worse.

“I was mad at Vince,” Paul Hornung said years later. “We could have scored 70 against them but he pulled the starters out early. He liked the Maras and didn’t want to rub it in. We had a tremendous team and we played a tremendous game.” Hornung had scored 19 points in the game by himself.

Football was much different in the 1960s than it is today, when people all over the country have television access to every game that is played. With rare exceptions, there were only three NFL games televised nationally during a season: the championship game; the Thanksgiving Day game in Detroit; and the exhibition game between the reigning NFL champions and college all-stars. Nevertheless, despite the lack of TV exposure nationwide, America was getting to know the Green Bay Packers.

Lombardi was receiving mail from throughout the country from people who started Packer fan clubs. People were finding out about the team from the little town through newspaper and magazine stories.

Hornung and Taylor were piling up yards on Lombardi’s famed Power Sweep, which was making his offensive line famous, especially the guards. Center Jim Ringo, guards Fuzzy Thurston and Jerry Kramer, and tackles Forrest Gregg and Bob Skoronski, who alternated at left tackle with Norm Masters, formed a unit that was second to none. The defense was led by linemen Willie Davis and Henry Jordan. Middle linebacker Ray Nitschke was beginning to make a name for himself as were Willie Wood and Herb Adderley, who made the Packers’ secondary one to fear for opposing quarterbacks.

And of course there was Starr, a seventeenth-round draft pick out of the University of Alabama in 1956. He was in charge of Lombardi’s offense. All of the above, with the exception of Kramer, Thurston, Masters, and Skoronski, would wind up in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

“Think of the names that were playing up there,” said Tom Matte, a former halfback for the Baltimore Colts. “It was just a fantastic time for football. The Orioles were a good baseball team but Baltimore was a football town. Green Bay was a good football town, the Cleveland Browns at the time, and the New York Giants, played in good football towns.

“Look what the Baltimore Colts and the New York Giants did for football in 1958 and ’59. Then Lombardi came to Green Bay. It was a time when people were looking for a national sport. Baseball had always been that, but to be honest with you, baseball fans are just not as enthusiastic as football fans. They’re just crazy. They love the game; they love the contact.”

The Packers were loved throughout Wisconsin. They played part of their home schedule in Milwaukee, one hundred miles to the south, halfway between Chicago and Green Bay, which became known as Titletown when the Packers won the 1961 championship.

Milwaukee had the Braves, who had moved to the city from Boston before the 1953 season. While the Packers of the fifties struggled to win, the Braves were popular and set a National League attendance record, drawing 1.8 million fans. They eventually gave Wisconsin baseball fans a winner, beating the New York Yankees in seven games in the 1957 World Series. Led by the home run duo of Hank Aaron and Eddie Mathews, the Braves returned to the Fall Classic the following year but lost game seven to the Yankees in Milwaukee. The Braves and Los Angeles Dodgers tied for the National League title in 1959, but the Dodgers won a playoff and went to the World Series. The Braves started to decline in 1960, and within a few years ownership was looking to relocate the club. The team moved to Atlanta following the 1965 season, leaving Milwaukee without baseball until 1970, when a group led by Bud Selig, then owner of an automobile dealership, bought the Seattle Pilots and made them the Brewers. Years later Selig would become commissioner of Major League Baseball.

County Stadium, the home of the Braves, also was a part-time home for the Packers, who began playing at least one game a year in Milwaukee beginning in 1953. When the baseball park was built, the Packers played two games a season there through 1960. When the NFL expanded from a twelve- to a fourteen-game schedule in 1961, Milwaukee picked up another home game.

Green Bay fans didn’t like sharing their team, but by 1962, the Milwaukee stadium could pack in over 46,000 fans, 7,000 more than Green Bay’s City Stadium held. Playing in Milwaukee was good for business, and it also helped the team create a bond with the entire state.

The Packers’ success from 1961 carried over into 1962 as they swept through six exhibition games and the first ten games of the regular season. Writers from the big newspapers and magazines continued to travel to Green Bay to tell their readers about the magic that was happening in the little town of 63,000 people. Before the 1962 title game, Time magazine put Lombardi on its cover, which proclaimed football “The sport of the ’60s.” The story referred to Lombardi as “the world’s greatest football coach.” His sport was overtaking baseball as the national pastime, and Lombardi’s Packers had become the face of the NFL.

During those first ten games in 1962, Lombardi’s men scored 34 or more points in six of those contests and recorded three shutouts. Their ninth win was a 49–0 whitewash of the Philadelphia Eagles, the team that had beaten them in the 1960 NFL championship game 17–13. The Packers had 37 first downs while setting a team record with 628 yards and holding the Eagles to 3 first downs and 54 yards.

The Packers finally suffered a loss when the Detroit Lions sacked Starr eleven times during a 26–14 win in the annual Thanksgiving Day game in Detroit. But they came back and won their final three games, although they struggled on the West Coast swing. They trailed the San Francisco 49ers 21–10 at Kezar Stadium before rallying with 21 second-half points for a 31–21 win. The following week at the Los Angeles Coliseum, they were pushed to the brink by the one-win Rams before escaping with a 20–17 triumph to complete the thirteen-win regular season.

The Packers were not the only football team being talked about in Wisconsin that year. The University of Wisconsin, the state’s entry in the Big Ten Conference, also was having a special season. The Badgers won their first four games before losing to Ohio State in Columbus, 14–7. The Badgers bounced back and continued to win. In their seventh game they administered a 37–6 whipping on unbeaten and top-ranked Northwestern, which was coached by Ara Parseghian, who in two years would be coaching at Notre Dame.

The Badgers finished the regular season 8–1 and ranked No. 2 in the country behind Southern Cal. Those teams met in the Rose Bowl and put on a wild show. The Trojans led 42–14 early in the fourth quarter before the Badgers made a furious rally that fell just short, 42–37.

Pat Richter, an All-American tight end for Wisconsin who would go on to have an eight-year NFL career with the Washington Redskins, said there was a strong bond between the Packers and Badgers. Richter, who was from Madison and also played basketball and baseball for Wisconsin, got to know many of the Packers at athletic banquets during and after that season because he shared the dais with them. In that classic game against Southern California, Richter set a Rose Bowl record with 11 catches for 163 yards. The Badgers wouldn’t return to the Rose Bowl for another thirty-one years, but they did it with the help of Richter, who, as Wisconsin’s athletic director, hired Barry Alvarez, a forty-three-year-old assistant coach from Notre Dame. Alvarez would lead the Badgers to three Rose Bowl championships.

“Milt Bruin, our coach, had a good relationship with Lombardi, who reached out to the state, and Milt took it upon himself to go up there and learn as much as he could,” said Richter, who played for Lombardi in 1969 during the coach’s one season with Washington. “Milt and his staff went to Green Bay and learned their offense. We actually installed the sweep type of offense, which was fairly innovative at that time. They didn’t have a big laundry list of plays. It was simple, but what you were taught you had to do well.”

The Giants didn’t start as fast as the Packers in 1962. They lost their first game in and were 3–2 and in second place in the Eastern Division before hitting their stride. Led by quarterback Y.A. Tittle, the Giants won their final nine games and finished the regular season with a 12–2 record for their fourth division title in five years. They clinched the title in the twelfth week of the season with a 26–24 win over the Chicago Bears.

Tittle directed a pass-first offense that was all about the big play. He threw for 3,224 yards and 33 touchdown passes. His favorite target was split end Del Shofner, who caught 12 touchdown strikes and finished the regular season with 53 balls for 1,133 yards, a staggering 21.4 yards per catch.

Frank Gifford, Lombardi’s left halfback when the coach was an assistant with the Giants, was now a flanker. Gifford sustained a serious head injury in 1960 after a violent collision with Eagles linebacker Chuck Bednarik, forcing him to retire for a season. Though not touching the ball nearly as much as he did when he was a ball carrier, Gifford was still productive in the regular season, catching 39 passes, including seven for touchdowns. Like Shofner, when he made a catch it was for big yards, as Gifford averaged 20.2 yards per play. The Giants could be explosive. They scored 398 points, and four times during their final eight games, they torched opposing teams for 41 or more points.

The Giants had last won an NFL title in 1956. They lost to the Colts in the 1958 game, the famous one that went to sudden death, and again to the Colts in 1959. From 1958 through 1962 they were one of the NFL’s most consistent teams with an overall record of 47–14–3, but the three bridesmaid finishes gave the team a reputation for not being able to win the truly big game. And the third of those championship losses, in 1961, was just plain embarrassing.

That game was played on a cold, relatively calm day in Green Bay. The temperature was 17 degrees, and the winds blew at ten miles per hour. Tittle struggled to throw, and the Giants squandered two early scoring opportunities before the Packers exploded for 24 points in the second quarter.

“We depended on the forward pass,” Tittle said. “We didn’t get the good weather, and it hurt us a lot.”

In 1962, the Packers were looking to repeat as champions; the Giants were looking to avenge one of the worst losses many players on the team had experienced.

The Packers had two weeks to prepare for the 1962 championship game, which was beneficial because they were a beat-up team. Among those hurting was Jim Ringo, who had a nerve problem in his right arm that caused it to go numb. Ironically, Ringo’s injury worsened in practice. In Nitschke, a biography of the Packers’ middle linebacker, Ray Nitschke said Lombardi pulled him aside leading up to the title game and instructed him to go after the Green Bay offense like it was the Giants’ offense. Lombardi was fearful his team lacked intensity leading up to the game, and he thought Nitschke could change that.

One day the middle linebacker hit Ringo so hard that it left the center with a pinched muscle in his neck. The pain ran down to his arm and became a serious problem in the days leading up to the game.

Following a workout at Yankee Stadium two days before the game, Lombardi asked Ringo how he felt. Ringo told the coach he couldn’t feel his arm and that he didn’t think he’d be able to play.

The exchange was witnessed by Dave Klein, a reporter for the Newark Star-Ledger. According to Nitschke, Lombardi lost his temper at the reporter for being there. Ringo was more diplomatic, telling Klein that if the Giants knew about his problem they’d go after his arm. He promised the reporter an exclusive interview following the game if he didn’t report on the injury. Klein agreed.

Hornung was playing, despite being mostly inactive since injuring his knee in the fifth game. Outside linebacker Dan Currie had missed three games with a bad knee, although he returned for the final game against the Rams.

The week before the game, Lombardi had a sign installed above the door leading to the Packers’ locker room: “Home of the GREEN BAY PACKERS ‘The Yankees of Football.’”

The sign served as motivation, but it may have also been a psychological move to get the Packers thinking of where the championship game was going to be played. Yankee Stadium was the sporting arena of the era. The house that Ruth built; the home of the team that had dominated major league baseball since the 1920s. Yankee Stadium also was the site of several historic college football games between Army and Notre Dame and also home to some of the biggest heavyweight title fights of all time. In 1927 Jack Dempsey came from behind to beat Jack Sharkey there. In 1936 German Max Schmeling knocked out unbeaten Joe Louis in the twelfth round at Yankee Stadium. They had a rematch two years later at the same venue, and Louis knocked out the German in the first round to win the title.

Equipment manager Dad Braisher adjusts a motivational sign in the team’s locker room in late December, 1962.

The Packers knew they would see a different Giants team than the one they faced in 1961. The Giants were looking for payback—and to prove that the 37-point loss the previous year was a fluke.

“We were concerned about the quality of team we were facing and playing on the road in ’62; that’s where the focus was,” said Bart Starr, who had his best season, completing 62.5 percent of his passes while directing the most potent offense in the game. “We had a lot of respect for the Giants, but I think the focus was more that it was a road game, in New York, where we would be facing a hostile crowd, so to speak. We also recognized the strength that the Giants had that year. They had excellent leadership, and Tittle was a very strong and talented quarterback.”

Still seething from the 37-point humiliation the year before, the Giants wanted the Packers to leave Yankee Stadium the way they had left Green Bay twelve months earlier.

“I’ve never been as anxious to play a game as this one,” Giants defensive end Andy Robustelli said at the time “We will absolutely kill the bastards. It’s the only way I’ll be able to forget about the one out there last year. It won’t be enough to just win the game. We have to destroy the Packers and Lombardi. It’s the only way we can atone for what happened to us last year.”

Lombardi knew there would be a sense of awe for many of his players to play such a prestigious game at Yankee Stadium. They had played at the cavernous facility in 1959, but it was a midseason game. This one was different: the Packers were going for their second straight title, and the entire nation would be watching.

The game had special meaning to Jerry Kramer, the Packers talented right guard. He broke his leg midway through the 1961 campaign and missed the championship game. He’d been on the sidelines in Green Bay and had celebrated with his teammates, but it was not the same. He worked hard during the offseason and had a terrific 1962 season, earning consensus All-Pro honors for the first time in his career.

The rematch with the Giants also carried added significance for Kramer because he had become the team’s kicker for extra points and field goals when Hornung injured his knee before the midway mark of the ’62 season.

“When we got to the game my main concern was not letting the team down, trying to make the field goals, trying to grab a hold of my composure,” Kramer recalled in late 2010. “We were in Yankee Stadium and I was about to wet my pants.

“Yankee Stadium was hallowed ground, and it was an awesome experience to walk into the stands, especially for me. With Hornung injured and me kicking out there, it was a pretty damn exciting time for me.”

The Packers were a running team, led by Taylor, the powerful fullback who during the season averaged 105 yards per game and scored 19 touchdowns, numbers that helped to beat out Tittle for the league’s Most Valuable Player Award. Even though the ground attack was the strength of his offense, Lombardi, after studying hours and hours of film on the Giants, was convinced Starr could beat them through the air. The game plan revolved around the pass, and many expected the championship game to be a wide-open contest between the league’s two highest-scoring teams.

The Packers led the NFL that season in eleven offensive categories, including scoring and rushing. The Giants, who scored 391 points, topped the NFL in total offense as they gained more than 5,000 net yards and had a league-leading 35 touchdown passes.

The game also featured many of the game’s greatest players, including fifteen that would land in the Hall of Fame. For the Giants: Roosevelt Brown, Frank Gifford, Sam Huff, Robustelli, and Tittle. The Canton-bound Packers were Herb Adderley, Willie Davis, Forrest Gregg, Paul Hornung, Henry Jordan, Ray Nitschke, Jim Ringo, Bart Starr, Jim Taylor, and Willie Wood. In addition, Giants’ owner Mara and Packers’ coach Lombardi would be voted into the Hall.

For all of these reasons and more, there was great national interest in this championship game. Pro football had been growing in popularity since the 1958 sudden-death championship game between Baltimore and the Giants. This rematch featuring the hard-hitting team from the NFL’s smallest market against the big city New Yorkers was going to be a treat for football fans throughout the country.

According to a story in the Press-Gazette, players on the winning teams would receive approximately $6,000; losing players would earn $4,000. Both amounts were records. The NFL would earn $632,000 from television, radio, and film rights, a considerable difference from the $75,000 the league made in 1951, the first time a championship game was nationally televised.

Game day came and any expectations of a shootout were blown away by a strong wind that swept throughout Yankee Stadium. Gusts ranging from thirty to forty miles per hour made for horrific conditions, especially with the temperature hovering around twenty degrees.

The Packers were ready. As the bus that carried the team and media members arrived at its destination, Nitschke leaped out of his seat and yelled, “Welcome to Yankee Stadium, home of the World Champion Packers.”

Defensive end Willie Davis recalled the field feeling like a “parking lot.” The grass was gone, and the dirt was frozen. Those who took the field had never remembered conditions being so primitive. At the time it was the coldest many players had felt on a football field. Some of those same players, who five years later beat Dallas in the infamous “Ice Bowl” when the temperature was minus thirteen degrees, recalled Giants Stadium feeling just as cold because of the wind.

“Vince (Lombardi) Jr. once told me he thought it was colder or worse than the Ice Bowl,” Kramer said later. “I remember the wind blowing like a bitch. We came out at halftime and our players’ bench—it was a small bench without a back on it, just two sides and the setting surface—the wind had blown the bench back onto the playing field. It may have blown maybe ten yards out onto the field. Our capes and all kinds of shit was being strung all over hell and back. The trainers were trying to pick everything up because of that wind. I don’t know what the wind chill factor was but it was bitter cold.”

The wind was so severe that it tore the American flag that flew in the stadium. One of the cameras used for the national telecast blew over. In the baseball dugouts, photographers built little bonfires to thaw out their cameras. Before the Packers kicked off to begin the game, the ball fell off the tee three times because of heavy wind gusts.

Despite the elements, the Giants fans were ready for the Packers. Shouts of “Beat Green Bay. Beat Green Bay” filled the stadium from the more than 62,000 that attended.

Fans in a team’s home market could not watch their team’s regular season and playoff games on television because of the NFL’s blackout policy, which was in place to protect gate receipts. Because of that policy, many residents of New York City piled into cars and traveled to hotels in Connecticut, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania so they could watch the game on TV.

The primitive conditions forced Lombardi to scrap his plan on surprising the Giants with a passing attack. As usual, the Packers offense would revolve around Taylor, whose every move was being followed by Sam Huff, the Giants All-Pro linebacker. Huff had help; the Giants couldn’t wait to hit Taylor over and over.

“They beat the shit out of Taylor,” Hornung remembered almost fifty years later.

Early in the game Taylor bit his tongue when he was tackled, causing him to swallow blood for much of the game. He also suffered a cut on his arm and was stitched up by team doctors at halftime. As his teammates tried to thaw out at halftime they heard Taylor scream in agony from the trainer’s room while he was being sewn up.

Despite the pain and physical punishment he was enduring, Taylor played like a champion. Of the Packers’ forty-six running plays, Taylor was given the ball thirty-one times, finishing with 85 of the toughest yards he would ever gain in a game. During the second quarter with his team up 3–0, thanks to a 26-yard first-quarter field goal by Kramer, Taylor scored the game’s only offensive touchdown on a 7-yard run that gave his team a 10–0 lead.

Years later Huff said, “Did everything I could to that sonofabitch.”

It turned out that Taylor was playing sick; he was diagnosed with hepatitis a week later.

Davis remembers Taylor being upset because he was considered second fiddle to the great Jim Brown, the Cleveland Browns fullback who led the league in rushing every year he played during his nine-year career—except in 1962, when Taylor won the title with 1,474 yards.

“He was always mindful of Jim Brown,” Davis said. “Nothing would have pleased Jim Taylor more than having a breakout game in the championship game so he could say to Jim Brown, ‘In your face.’

“The Giants really took it to him that game. He was literally beat up by the end of the game and even into the next week when they discovered he had a sickness. Still he played a tough game and he didn’t get one free yard.”

Following the game, while talking to reporters, Huff paid the ultimate compliment to the Green Bay fullback.

“Taylor isn’t human. No human being could have taken the punishment he got today,” Huff said. “Every time he was tackled it was like crashing him down on a cement sidewalk because the ground was as hard as pavement. But he kept bouncing up, snarling at us, and asking for more.”

Taylor told reporters that the Giant players taunted him throughout, calling him over-rated.

“I never took a worse beating on a football field,” Taylor said. “The Giants hit me hard, and then I hit the ground hard. I got it both ways. I just rammed it right back at them, letting my running do the talking. They couldn’t rattle me.”

Meanwhile, the Giants offense couldn’t get into the end zone. Tittle kept trying to go long, but the gusting winds sometimes pushed the ball several yards back. The Giants had success with short passes but 3 turnovers—1 interception and 2 fumbles—were devastating.

“The ball was like a diving duck,” Tittle said after the game. “I threw one pass and it almost came back to me. The short ones worked, but the long ball broke up. We needed the long one.”

After the Packers took a 3–0 lead Tittle used short passes to drive to the Packers 15-yard line. Tittle had tight end Joe Walton open on the goal line when he delivered a pass. But Nitschke got his hand on it, tipping it in the air. The ball was intercepted by Dan Currie, who made a long return but staggered as he fell to the ground because his knee gave out. He looked like a punch-drunk fighter trying to stay on his feet before hitting the canvas.

“I go about 30 or 40 yards and it starts to waver and wobble,” Currie said after the game. “It’s not that strong yet.”

The Giants’ lone score came in the third quarter, and it was without any help from the offense. Packer flanker Boyd Dowler, who also was the team’s punter, had a bad leg, which kept him from punting. That chore fell to Max McGee, who before Dowler arrived had been the punter. He took a snap while standing in his end zone, and Giants defensive back Erich Barnes swooped in untouched and blocked the kick. Giants special team player Jim Collier fell on the ball in the end zone for a touchdown that cut the Packers lead to 10–7.

The crowd at Yankee Stadium was re-energized, and shouts of “Beat Green Bay” rose louder than ever. But Tittle just couldn’t deal with the wind. He needed 41 attempts to complete 18 passes for 197 yards. Shofner had 5 receptions for 69 yards but never could get past cornerback Jesse Whittenton, who played much of the game with limited mobility after suffering a jarring hit to the ribs delivered by Giants fullback Phil King. Had it not been so windy, Shofner may have been able to get downfield for an opportunity for a long play.

“I busted up my ribs in the first quarter,” Whittenton said after the game. “King had the ball on a sweep or a screen—I don’t remember which—and I came up and got it in the side. I had figured to play Del tight, but after that I had to drop off him because I couldn’t move around as good as usual. I had to give him the short one, and I’m glad they couldn’t throw the long one.”

The Packers secondary suffered another loss when safety Willie Wood was ejected in the third quarter after he unintentionally knocked down back judge Tom Kelleher. Wood had tipped a pass directed at Shofner and Kelleher called it interference. Wood approached the official and began to protest when he slipped and hit Kelleher, causing him to fall down. Wood was replaced for the remainder of the game by one-time starter Johnny Symank.

“I was covering Shofner on a crossing pattern,” Wood said after the game. “I went for the ball and suddenly I saw the white handkerchief go down. I jumped up to protest and my hand must have hit him in the chest.”

Said Kelleher, “In my opinion, Wood committed an overt act in striking me and that called for disqualification. If I had bumped into him it would have been a different matter.”

The rest of the scoring was done by Kramer, who during the regular season had made 38 of 39 extra-point attempts and was good on 9 of 11 field-goal tries. He booted a 30-yarder with four minutes left in the third quarter for a 13–7 lead.

Then, with 1:50 remaining in the game, Kramer capped the scoring with a field goal from 29 yards for a 16–7 lead, which on this brutal day was enough to secure a second championship for the team that resided in the NFL’s smallest city. As he left the field, Kramer was swamped by his joyous teammates. He had been forced to watch the 37–0 win the previous year because of a broken leg, and now he was a championship game hero.

“If I made that kick, that pretty much meant the game,” Kramer said. “So in those situations you try to focus on keeping your head down. That was my focus at that time, keeping my head down and following through. Don’t look up prematurely; make sure you hit the ball squarely. I believe I aimed the ball outside the right goal post. The wind was whipping into the post, just circling in the stadium going round and round. When the thing went through I was afraid I was going to miss it, afraid I was going to be the goat, so it was great relief more than anything else.

Jerry Kramer, who took over kicking duties for the team after the injury to Paul Hornung, practices his technique during a workout.

“All the guys were jumping on me. I was feeling like a wide receiver or a running back for a moment. I never had that kind of reaction before.”

Dowler recalled how the big offensive guard swung his foot into the football.

“He jabbed at the ball,” Dowler said. He hit it pretty square, pretty solid, and they went through. It was a pretty good accomplishment when your right guard kicks three field goals in the championship game.”

On most days Kramer’s point production might have been good enough for him to be selected as the game’s MVP by media covering the game. That honor instead went to Nitschke, the bald, ferocious middle linebacker who had tipped the touchdown-bound pass and also had recovered two fumbles.

“The players voted me the game ball, which is an example of what life is like for a lineman in that business,” Kramer recalled. “The writers voted Nitschke the game’s MVP, and he got the Corvette. I got the game ball, which is a lot more than what most offensive linemen get.”

In newspaper accounts of the game, Nitschke seemed genuinely touched to be named MVP.

“It’s a great big thrill,” said Nitschke, who died in 1998. “It’s like a dream. You dream of a thing like that happening to you.”

Later that night the menacing linebacker, wearing dark-rimmed glasses and a suit, appeared on What’s My Line, the prime-time game show that ran every Sunday night on CBS. A group of panelists would ask questions of a guest, trying to figure out his or her occupation.

Dorothy Kilgallen, one of the regulars on the show, asked Nitschke if he was a member of the government.

Arlene Francis, another panelist, said, “He’s very quiet and reserved, which would lead one to believe he is with the Giants, but I believe he’s with the Green Bay Packers.”

Following the game, players talked about the hitting that occurred on Yankee Stadium’s frozen field.

“That was the toughest game I ever played in,” Hornung said.

Packers left guard Fuzzy Thurston added, “You could really feel it when they hit you out there today, you could feel it in your bones. The Giants were the best today I’ve ever seen ’em. I thought we were a lot better today too than we have been.”

McGee, the team clown said, “That was the hardest-hitting game I ever saw, and I watched most of it. I didn’t know a human body could get that cold. And still survive.”

The Giants felt the disappointment of coming up short in another championship game, although their performance was significantly better than the one a year earlier.

“We knew it was going to be a hard-hitting game and that’s what football was,” cornerback Dick Lynch said. “It was a great game just as far as making tackles and just whacking guys. I’m sorry we lost. It was horrible.”

“It was a great game,” the Giants’ Gifford said. “We’re still the better team.”

That statement was hard for Gifford to defend. The weather had affected both teams, and regardless of the conditions, the Giants had failed to score a touchdown in two championship games against the Packers, who, including the postseason, concluded a two-year stretch with a 26–4 record. In fact, going back to a midseason game in 1961 won by the Packers, 20–17, the Giants offense had not scored in ten quarters against the Green Bay team that truly now was the face of the NFL. The 1962 championship-game victory made Lombardi and his players that much more recognizable throughout the country.

In the end the only words that mattered were spoken by the coach of the winning team.

“I think it was about as fine a football game as I’ve ever seen,” Lombardi said. “I think we saw football as it should be played.”