Читать книгу The Bleeding Edge - Bob Hughes - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

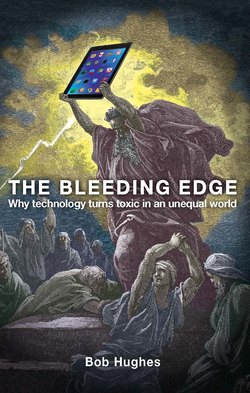

From water mills to iPhones: why technology and inequality do not mix

The middle of the 20th century saw the world move in the direction of greater equality, including the rise of the welfare state – and that produced egalitarian hopes for computing. But these were dashed by the neoliberal policies from the 1970s onwards, which saw a return to medieval levels of social inequality. Medieval history shows what happens when new technologies are introduced into very unequal societies, as with the water mill and then the gun. The precedents are not encouraging.

Computers were one of a constellation of transforming developments that broke through into the real world during the politically contested and chaotic years during and just after the Second World War, and not just in the ‘hard sciences’.

Old shibboleths about the nature and potential of human beings, how they should be treated, and about how society should be ordered, were being demolished and discredited by new currents of work in the social sciences (anthropology, psychology, neuroscience, education) and by people’s own direct experiences in the War. Understandings of how the planet itself worked were being elaborated at a breakneck rate with the brand-new sciences of cybernetics and general systems theory. Many people thought that these understandings, which had developed in lockstep with the development of computing machinery and signal processing, were much more significant for humanity’s future than the machinery itself. The world was being recognized as a whole system, and so was knowledge.

All economic and political trends seemed to be pointing toward greater and greater equality. The brief failure of ‘business as usual’ that allowed the likes of Alan Turing and Tommy Flowers to work together was one of millions of instances of a much bigger egalitarian and humanistic turn that was struggling to shape the course of events globally.

Old and entrenched doctrines of innate inequality and racial superiority, so widely held and even respectable before the war, were abruptly silenced by the defeat of the Fascist powers, and the exposure of the unambiguous horror of the Nazi ‘final solution’ to its ‘Jewish problem’. Fascism ceased to be respectable, and there was a general stampede among those who had supported it during its heyday, to higher moral ground. The concept of ‘crimes against humanity’ gained legal force for the first time, and political leaders were jailed, put on trial and sentenced for committing them.

The post-War political climate was shaped to a surprising degree by people who had wielded pathetically little military muscle during the conflict: resisters and rescuers now found themselves almost the sole uncompromised bearers of the West’s claims to moral superiority. Leftwingers and liberals, who had been pre-eminent in the resistance movements, briefly found themselves at or at least in sight of the top table. One of these was the late Stéphane Hessel, author of the 2011 bestseller Time for Outrage!1 (published in French as Indignez-vous!), which sold millions of copies worldwide, especially among supporters of the various mass protest movements that broke out after the financial crash of 2007/8.2 Hessel was a German-born, Jewish member of the French resistance who survived capture and torture, escaped, and ended the war as part of the team responsible for drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948.

While France was still under Nazi occupation, its National Resistance Council (the CNR) drafted a Charter demanding, for example,

a complete Social Security scheme aimed at guaranteeing means of subsistence for all citizens, in every case where they are unable to procure these through labor, the management of which will belong to representatives of the interested parties and the state [and] a pension that will allow old workers to end their days with dignity.

The Resistance was rudely sidelined by the incoming De Gaulle government, but even so, the extent to which its proposals were implemented is striking (especially when compared with social provisions at the beginning of the 21st century).

The Scottish writer Neal Ascherson has observed that, independently of each other, in ‘the years between, say, 1943 and 1947… resistance movements from Poland to France and southern Europe developed similar programs for revolutionary democratic renewal after the war’.3 Britain’s welfare state was part of the phenomenon, perhaps reflecting a feeling many British people had of having in a sense lived ‘under occupation’ by Winston Churchill – whom they comprehensively ejected from office when elections were resumed in 1945.

All of the victorious powers introduced some kind of basic welfare provision for their citizens: pensions, unemployment benefits, healthcare and even that essential preserve of the rentier class, housing.

Major firms and industries were nationalized with popular approval. On France’s liberation, the owner of the Renault automobile company, Louis Renault, was arrested as a collaborator and his company was confiscated. The following year the rest of the automobile industry, the whole banking sector and the coalmining industry were nationalized.

The Right was even more deeply and durably discredited in Germany, where strong social-justice measures were introduced after 1945. Trade unions were given a stronger role, including seats in German boardrooms. The French economist Thomas Piketty has argued that this has helped maintain the country’s prosperity by restraining the scope for runaway managerial incomes.

The social groundwork was set for a progressive shift towards greater and greater equality – in line with the uncontested general acceptance that all human beings were, in fact, equal.

The world was suddenly full of people who had discovered capacities for heroic and creative achievement, and interests and experiences they never would have dreamed possible a few years earlier. Women in their tens of thousands had escaped from domestic duties, done ‘men’s jobs’, including some of the most dangerous and exciting ones. There were thousands of people like Tommy Flowers who had lived and worked at the outer edge of technological and human possibility, and resented being dragged back into their allotted social niches and told to stay there.

The conditions needed for people to realize their potential became, however, a legitimate subject of research. Education was expanded massively in all the main economies, and there was a proliferation of new, more ‘liberal’ educational regimes. For the first time in centuries, it was becoming official policy that all human beings should be treated humanely, and this was backed by new international laws. There was also a widespread sense that the future would be one of greater equality within and between nations, rather than less.

It is true that much of the new work in psychology served a social-control agenda – such as harnessing propaganda and finding better ways of getting troops to follow orders – but it also included radical departures in, for example, understanding child development and mental illness.

Both during and after the War governments and aid agencies were overwhelmed with traumatized people and orphans. In Britain, Wilfred Bion pioneered what became the group therapy movement for the treatment of mental distress, when the War Office found itself in charge of thousands of men who had been emotionally shattered by the ordeal of Dunkirk.4 While working with evacuee and refugee children, John Bowlby developed his theory of attachment and the damage caused by separation, which profoundly altered views about parenting and the treatment of children in the post-War years. Bowlby’s colleague Donald Winnicott developed a theory of the vital importance of play.5 These theories have subsequently done nothing but grow in their explanatory and therapeutic power.

Genocide, and the Nazi defeat, triggered a wave of research into the human capacity for cruelty. Why do apparently decent people, in some circumstances, become murderers and torturers, while others feel compelled to become rescuers and resisters, whatever the risks?

Theodor Adorno’s colleagues in New York discovered plenty of potential for complicity in brutal regimes among ordinary Americans.6 Through scores of interviews, they identified a strong link between strict, punitive parenting, and attitudes predisposing people to support fascistic regimes and authoritarianism in general. Stanley Milgram7 and others began to expose the unwelcome truths about the ease with which people can be persuaded to inflict lethal harm on others.8

THE ‘GREAT COMPRESSION’

This was, above all, the period in which income and wealth differentials began to shrink; it has been called ‘the great compression’.9 It is still not entirely clear when or how the compression began, but it certainly ended in the 1970s, when the ascendance of neoliberal economic policies threw the process into reverse, initiating what subsequent economists have called ‘the great divergence’ in incomes and wealth.10

Progressive taxation was adopted throughout the West – at far higher levels than had ever been contemplated before, and not always by left-wing governments. A proposal for a mere two-per-cent extra tax on the wealthiest had been howled down and dismissed out of hand in the France of 1914, but a rate of 50 per cent was successfully introduced as early as 1920 – by a reactionary rightwing government that sensed trouble otherwise.11 The US led the rise in top tax rates during the war until the 1970s. In 1972, the Democrat presidential candidate George McGovern even proposed raising the top rate from 77 per cent to 100 per cent, to support a guaranteed minimum income. He was defeated, however, by the incumbent, Richard Nixon.12

The Second World War obviously necessitated a great levelling simply so that warring nations could overcome the problems of supply – for example, during the U-boat war in the Atlantic. But a levelling tendency had already been visible in France in 1920, and in the US after the financial crash of 1929. Demand for large, luxury cars fell abruptly; labor historian Rob Rooke records that demand fell steadily from 150,000 sold in 1929 to only 10,000 a year by 1937. Perhaps this was because it no longer felt right to drive in luxury when people were starving, and perhaps, following rumored or actual attacks on wealthy limousine-owners, rich people suddenly felt ‘that ostentatious displays of wealth could cost them their lives’.13

This was part of a shift that prepared the moral climate for the New Deal reforms of Franklin D Roosevelt, who was elected by a landslide in 1932 while a socialist anthem, Yip Harburg’s ‘Brother, Can You Spare A Dime’, stood for months at number one in the popular music charts.

The change had an enduring effect even on hardliners like General Douglas MacArthur, who earned public vilification in early 1932 and helped turn the tide of US opinion in favor of Roosevelt when he used tanks to crush a protest in Washington by the ‘Bonus Army’ of destitute World War One veterans and their families. In 1946, MacArthur took charge of Japan’s occupation and reconstruction. This involved brutal suppression of leftwing forces but MacArthur also pushed through some surprisingly radical reforms, which have helped to maintain Japan’s relatively greater equality today: land reform; a massive unionization campaign among industrial workers (albeit preceded by suppression of radical unions); the breaking-up of financial, industrial and media monopolies; and even subsidies for minority media.

The levelling trend was also galvanized by the sheer fact of a large, powerful and widely appealing rival value system in the USSR and, after the War, a greatly expanded Communist bloc of countries. Whatever the conditions of life actually were in those countries, their vigor and resilience were unquestionable, and, however corrupt their governing systems may or may not have been, they were propelled by a cause for which people were prepared to suffer and die, and which also inspired millions of people within the capitalist world. Capitalism’s frontiers had become very close.

The Soviet ambassador to London, Ivan Maisky, described in his personal diary how, in cinemas after the Soviet victory at Stalingrad in 1943,

[Stalin’s] appearance on the screen always elicits loud cheers, much louder cheers than those given to Churchill or the king. Frank Owen [editor of the London Evening Standard] told me the other day… that Stalin is the soldiers’ idol and hope. If a soldier is dissatisfied with something, if he has been offended by the top brass, or if he resents some order or other from above, his reaction tends to be colorful and telling. Raising a menacing hand, he exclaims: ‘Just you wait till Uncle Joe gets here! We’ll get even with you then!’14

Communist combatants did not always identify so readily with Stalin, especially those who had fought in the International Brigades for the Spanish Republic and seen Stalin’s brutal and counter-productive takeover of the anti-fascist forces. Stalin’s 1938 pact with Hitler had disastrously undermined French and German communists’ struggles against fascism at a critical time.

After the War the French Resistance was sidelined and belittled by the brusque and professional-looking government of General Charles De Gaulle but it was hard to ignore the fact that the unquestioned heroes of the situation had not been the men in the impressive uniforms, but those much more ordinary people who had faced and suffered hardship, torture and death in the Resistance, or who had saved others from deportation and murder.

The name of Jean Moulin, the Resistance co-ordinator tortured to death by the Lyon Gestapo in 1943, was given to thousands of streets, squares, public parks and schools. None were dedicated to Pierre Laval, the Vichy prime minister who had assured the Nazi bureaucrats that ‘our Jews are your Jews’, and enforced targets for roundups and deportations that put many of his German opposite numbers to shame.15 Yet thousands and perhaps millions of French people still regarded Laval as a responsible politician, and many of his colleagues continued to enjoy distinguished careers. Nonetheless, by the end of the Second World War, governments almost everywhere seemed to be embroiled in a conscious competition to occupy the ‘moral high ground’.

The greater equality prevailing in the Scandinavian countries and in western Europe in the post-War period has been attributed to the sobering effect on those countries’ elites of a well-armed communist country just over the border.16 World Bank researchers deduced that a similar phenomenon was at work in the countries known in the 1990s as ‘Asian Tigers’ (Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia). In a 1993 report, The East Asian Miracle, the Bank’s economists described how these countries had achieved big reductions in inequality between 1960 and 1980, and concluded that the policies had been in response to ‘crises of legitimacy’, arising from the presence nearby of communist rivals.17

EGALITARIAN HOPES FOR COMPUTING

In various places, but notably in Scandinavia, this moral shift not only affected social organization but also influenced global computer development.

In 1946 Norway’s post-liberation government introduced a full-blooded regional policy not unlike the one adopted in 1959 by a very different-looking government in Cuba after the overthrow of the Batista regime: no community, no matter how small or remote, was to be denied the full range of public services or work opportunities enjoyed by towns; rural industries were to be protected. The computer pioneer Kristen Nygaard became national spokesperson for this policy in the 1990s:

After the last world war we… decided that Norway should not deteriorate into a few densely populated areas around the large cities. Norway should exist as an interplay between vital local societies scattered all over the country. [… We] must keep our scattered settlement pattern, with an infrastructure covering and linking together all populated areas in the country. We cannot ‘turn on and off’ the local societies at will. A population returning to depopulated districts after a couple of decades will meet a deteriorated infrastructure, and will suffer from the loss of very important ‘tacit knowledge’ accumulated about the use of the land and resources during centuries of uninterrupted use and transfer of knowledge.18

For Nygaard, this was part of a radical politics that began in his childhood under Nazi occupation and which informed his approach to computerization. He and Ole-Johan Dahl invented the now-standard technique known as Object-Oriented Programming in 1965 specifically to support that kind of policy. Their computer language, SIMULA, was the starting point for most of the computer languages in use today, but it was at first regarded with suspicion as the work of ‘left extremists’.19

Nygaard and others like him (including, famously, the founder of cybernetics, Norbert Wiener) believed that computers would have to come under democratic control or they would lead to disastrous imbalances in society. He involved the Norwegian Iron and Metal Union in discussions and, in the late 1960s, they established the right of workers to share control of the way new technology entered the workplace. This became national policy under the Data Agreement between unions and employers in 1975.

A tradition of ‘participatory design’ was established throughout Scandinavia where (in principle at least) workers guided the design of new technologies. Like object-oriented programming, these initiatives did not inevitably produce egalitarian results.

For example, one of the first ‘desktop publishing’ (DTP) systems emerged from a participatory design project aimed at ‘work enrichment’, under workers’ control, at the offices of the Swedish newspaper Aftonbladet at the start of the 1980s.20 Not long afterwards, DTP was helping newspaper owners to get rid of print staff and journalists in droves. The idea of working from home, which became such a very mixed blessing, started here, with the ‘telecottage’ movement – first in Sweden and then Japan – aimed originally at keeping rural communities alive and even promoting a population shift from towns to the country.21

These and similar initiatives became by imperceptible degrees part of the post-1980 drive, and especially after the rise of the Web, to commodify the computer, gain competitive advantage and boost sales, under the rubric of ‘usability’.

THE RETURN OF MEDIEVAL ECONOMICS

The ‘great compression’ ended during the 1970s, giving way to what economist Paul Krugman has called ‘the great divergence’ of incomes and wealth within and between nations, at around the same time as computers and digital electronics began to become a major force in economic life.

By the late 1970s, there was much talk in political and journalistic circles about ‘the coming of the microchip’ – the first of a wave of similar frenzies accompanying the arrival of the internet (and especially, the World Wide Web) in the 1990s, and social media and cloud computing two decades after that.

Computers and electronics have been blamed for the Great Divergence, and are certainly implicated in it. But other, explicitly anti-egalitarian forces were also at work. These included the warlike and anti-democratic policies of Richard Nixon (US President from 1969 until 1974, when he was forced to resign), and in particular the ‘Nixon shock’ of 1971: his decision to deal with the inflation caused by the US’s war in Vietnam by allowing the dollar to ‘float’ against other currencies. This effectively demolished the post-War Bretton Woods system whereby global currencies had remained relatively stable, and plunged poorer countries into debt from which they have never recovered.

This deliberate lurch into inequality imposed its own timeless logic on the new technologies as they developed. But via them, it also had a huge impact on the world of work and consumption – as well as on the environment.

It has been argued that social inequality shapes societies according to a kind of built-in ‘grammar’, so that all unequal societies down the ages segregate people in the same kinds of ways, and develop similar social mechanisms for controlling them, with similar consequences.22

The scene today looks modern, and very different from even the recent past, if you consider only its ephemeral features (the fashions, the devices that people use, their job titles and so on). But if you look past them at the social structures underneath, and their environmental consequences, we are witnessing something very like a lurch back in time; not quite back to the Dark Ages, but certainly back to the 16th century and perhaps even to the 13th century.

Until the 17th and 18th centuries, the severest environmental impacts were confined to northwestern Europe and its immediate periphery. Today the same kinds and patterns of impact, and the oppressive social quirks that go with them, are observable globally.

Global inequality today is about the same as it was in the late Middle Ages in the first, tiny capitalist economies, in northern Italy and the Low Countries (modern Belgium and the Netherlands): around 0.7 on the Gini scale, which would award a score of zero to a society where wealth or income were distributed completely equally, and a score of 1.0 to a society where a single individual owned everything. The Gini index is a relatively blunt instrument, but many analysts of past inequality have used it, making it possible to compare a wide range of societies over time.

Various studies have found that this ‘north-European norm’ of 0.7 is without precedent in world history. No previous society had ever sustained anything like it for very long – not even ancient Rome23 or Egypt.24 But among the capitalist states that emerged in Europe from the 15th to the 19th centuries, coefficients of 0.7 or higher were common. A demographic historian, Guido Alfani, has worked out that:

in Paris at the beginning of the 14th century, the Gini index of wealth inequality was about 0.7; in London, it was 0.7 in 1292 and 0.76 in 1319. [Then, in the 15th century, in Italy, the coefficient] for the cities of Pistoia, Pisa, Arezzo, Cortona, Prato, and Volterra … was about 0.75. In Florence it was higher, reaching 0.785.25

In 1800, before European expansion had started in earnest, global inequality was insignificant. According to many historians, life was generally better for Chinese and Indian peasants than for their British counterparts.26 By 1820 (after the end of the Napoleonic wars) things were changing. The global Gini coefficient was somewhere around 0.50, and rising steadily.27 Branko Milanovic and Christopher Lakner have estimated that, by 2008, global income inequality was around 0.705, but possibly as high as 0.76, when adjusted for under-reporting of top incomes.28 One could say that Boccaccio’s Florence had taken over the world.

FOR ELECTRONICS, READ TEXTILES

The inequality embodied in something like an iPhone could not be more different from the egalitarianism that made it possible, but it is not without precedent. Whereas today’s most insecure workforces survive by assembling electronic devices, in late medieval Europe they were producing fashion textiles. Rapid obsolescence and highly atomized, precarious workforces were and are characteristic of both industries.

By the 16th century, entire populations in Europe depended for their very existence on this kind of textile production, and fashion textiles had become an ‘engine of growth’ of greater significance even than agriculture. Their production was organized for maximum profit on the ‘Verlag’ or ‘putting-out’ system: what we now call ‘outsourcing’.

All over Europe, merchant entrepreneurs were bypassing guild-based workers, who knew their trades from end to end, and employing networks of mainly rural, often largely female and/or juvenile workers, each specializing in some tiny part of the process but unable to comprehend let alone influence the course of the events on which her or his life came to depend. For the first time, there was ‘no such thing as a job for life’ for whole categories of the population. As now, livelihoods could and did vanish in a moment, with a change of fashion or of international prices, or the capitalist’s discovery of another, cheaper source of labor elsewhere. Outsourcing was already the name of the game, and so was obsolescence.

It can now sound naive to suggest that the biggest profits from any product should be found at or near the place where it is produced (the world’s richest countries might then be in Africa, for example). But that was always the case in traditional societies and the tendency is by no means passé. It still applies, very emphatically, to the work of top-echelon barristers, management consultants, surgeons, artists and financial advisers. It is still the case to some extent where labor still has strong negotiating power. But as one descends the gradients of power the reward-to-labor ratio goes into reverse and the big amounts migrate as far as they possibly can from the point of production.

The great French medievalist Fernand Braudel established that distance was ‘a constant indicator of wealth and success’ in the first capitalist economies.29 In the Venetian sugar trade of the 15th century ‘production was never the sector in which fortunes were made’.30

[A] kilo of pepper, worth one or two grammes of silver at the point of production in the Indies, would fetch 10 to 14 grammes in Alexandria, 14 to 18 in Venice, and 20 to 30 in the consumer countries of Europe. Long-distance trade… was based on the price differences between two markets very far apart, with supply and demand in complete ignorance of each other.31

For comparison, at the time of the Foxconn suicides in 2010, workers making Apple iPhones and similar products received a basic wage of $130 per month: about one 31,000th of the annual salary of Apple’s then-CEO, the late Steve Jobs (an estimated $48 million32). This was actually a relatively modest differential by electronics industry standards, because Foxconn and Apple were at least paying the minimum wage at the time, and Steve Jobs was only taking a nominal salary from Apple of one dollar a year (most of his income came from his shares in The Walt Disney Company).

In terms of where the bulk of the profit went, a Silicon Valley research company estimated in 2010 (by taking an iPhone 4 apart) that only $6.54 of its $600 retail price ended up at the point of assembly in Shenzhen: just over one per cent. The rest went to materials and components suppliers ($187.51), ‘miscellaneous’ ($45.95) and profit ($360, 60 per cent of the total).

What the latest analysis shows is that the smallest part of Apple’s costs are here in Shenzhen, where assembly-line workers snap together things like microchips from Germany and Korea, American-made chips that pull in Wi-Fi or cellphone signals, a touch-screen module from Taiwan and more than 100 other components.33

The components, whatever their nominal country of origin, are also made under a similar or harsher regime so, here too, a tiny fraction of their value ends up in the places where human labor is involved, which might be in one of the poorer regions of China, Indonesia, the Philippines or Mexico. To reiterate: this is the analysis for a relatively ethically produced product. The norm is much more extreme for other electronics products, and for other industries. An analyst of the global garment industry, Pietra Rivoli, commented to the authors of the article quoted above that ‘the value goes to where the knowledge is’: a dynamic that began with capitalism itself.

In contrast to the situation in the great empires of the East and South, the great fortunes of Europe’s late medieval and early modern period were also made ‘where the knowledge was’, and power politics ensured that it remained as far from the point of production as possible.

KNOWLEDGE-BASED WEALTH

We talk today of ‘the market economy’ as if we mean a single thing that we all understand but, in his groundbreaking work on global economic history, Braudel pointed out that the term covers two very different things.34 It refers to a market in the traditional sense, still found all over the world, where everyone can see everything that’s on offer, who’s offering it and what they want for it, and where terms, quality and sometimes even prices are regulated in a way that everyone understands. But it also refers to a capitalist market where the only people who have that information, and the means to get it, are the capitalists themselves. The name of the game is to get as much of that knowledge as possible, while keeping it from anyone else.

Our conventional fiction is that market knowledge is available, instantly, to everyone, so that we can all immediately take our custom to whoever offers the best value, driving out inferior quality and boosting high quality as we do so. Braudel’s examination of the ledger books and letters of the first great capitalists – the powerful Venetian, Florentine, German and Dutch merchants of the late Middle Ages – reveals what a fiction that has always been. These men were true entrepreneurs in the modern sense. They could be literally staking their entire wealth on the accuracy of the information they had; every scrap was valuable and guarded jealously (so these documents were kept in strongboxes, along with bullion and jewels). The biggest money was in overseas deals, where privileged knowledge could be exploited most, so merchants had good reasons for persuading the state to protect their trade and enforce compliance.

This panopticon-like ‘knowledge economy’ was unknown in many of the world’s other advanced economies until much later and then introduced only through force (massive force, in India and China). The sociologist Maria Mies has described how, in Burma, markets were run by women when the British arrived in 1824. The markets were well-regulated, open affairs that couldn’t easily be manipulated. The women who ran them also had their own parallel information networks and power structures that counterbalanced those of male society. This was apparently not macho enough for Imperial tastes. Britain’s methods for bringing Burma into the modern world involved conscripting Burmese men and teaching them harsh, military virtues, and putting women in their place through a ‘housewifization’ policy.35

The ‘knowledge-based inequality’ described by Braudel only arises when a merchant elite can rely on having privileged access to market information. European merchants were the first ones who could build businesses, industries and economies this way. They, uniquely, could increasingly count on state support to enforce their positions, and this was possible because medieval European states were relatively small and weak, and therefore easily dominated by pressure groups. New technologies emerging at that time (especially firearms and ocean-going ships) allowed these hitherto insignificant states to launch themselves on the world stage.

The Belgian historian Eric Mielants argues that capitalism is precisely what happens when a merchant elite takes over a state’s judicial and military apparatus, and deploys it to protect itself against risk, at the expense of other groups. Abroad, the state’s ships could be increasingly relied on to protect and monopolize trade routes and, nearer to home, the state’s power could be used to define who had access to justice and who didn’t:

Burghers, for instance, could not be tried outside their own city and were not to be imprisoned outside city walls, nor could any non-citizen testify against a citizen.36

The city became a ‘power container’, to use Mielants’ term. ‘Up to ca 1500 the city states were the “power containers” that made this… underdevelopment possible; after 1500, the emerging nation states performed this function.’37 The local countryside became an ‘exploitable periphery’ from which surpluses were extracted up to and beyond the capacity of the people to sustain themselves, or of the land to renew itself.

This was done by direct taxes and the creation of indebtedness, as well as by monopolies and laws controlling labor. The modern parallels are striking. Another medievalist, Peter Spufford, pointed out in 1988 that this was a colonial relationship in miniature:

In the 1280s the countryside of Pistoia supported a tax burden six times as high as that paid by the city. This excessive tax burden was only part of the sucking-dry of the contado by the city at this period. In Tuscany, payments from the countryside to the city greatly exceeded payments from the city to the country. The countryside fell into a state of endemic debt to the city. Repeated and continuous loans from the city to the countryside, and the purchase of rent-charges on the countryside by city-dwellers, only made the situation worse. Contadini were compelled to concentrate on cash crops rather than their own needs, and a cycle of deprivation was set up not unlike that in parts of the Third World today.38

The high-profit industries, like textiles, were built on cheap, controllable labor, so border controls became an important part of the dynamic, initially between town and countryside. Passports of various kinds became prevalent from as early as the 12th century (in the form of confession certificates), along with distinctive clothing and badges for the least favored groups (Jews, Gypsies, the unemployed), detention, expulsion and even ‘carrier’s liability’ (fines for those ‘people traffickers’ who tried to sneak vagrants into town in the backs of wagons or on barges). Controls intensified with the adoption of paper (a ‘write-once’ medium, not easily falsified) and the development of print technology in the 16th century. Johannes Gutenberg’s early career was built on the manufacture of pilgrims’ badges, and he used his press initially to mass-produce indulgence certificates (the lucrative ‘cash alternative’ to penance, against which Martin Luther was later on to rebel, in 1517). The proceeds funded production of his Bible in 1455.39

None of these restrictions applied to elites, who could go wherever they liked. Foreign elites were welcome within the charmed circle, insofar as they were helpful – just as the elites of ex-colonial countries are today, sending their children to Western universities, their money to Switzerland and attending the same elite events as their international peers.40 This pattern was established at least by the early 12th century during the ‘Northern Crusades’ (the context of Eisenstein’s film Aleksandr Nevsky), which had the economic effect of encouraging eastern-European dependence on supplying low-priced raw materials to the West. A historian of those events, Eric Christiansen, describes a very modern-sounding relationship between rulers and foreign merchants:

[Rulers] patronized foreigners who could bring them wealth, information and military skills or entertainment, and tried to create conditions which would attract them… The Russian princes insisted that, if a Russian borrower went bankrupt, his foreign creditors were to get satisfaction first, and that rates of interest for long-term loans should be low, to suit the long-distance trader… This common pursuit of wealth was the privilege of a small class of specialists, the international trading elite.41

THE FIRST MODERN ENVIRONMENTAL CRISIS

Peripheralization led to remorseless depletion of natural resources. Two Belgian researchers, Katharina Lis and Hugo Soly, calculated that, by the beginning of the 14th century (the century of the Black Death), landowners were taking 50 per cent or more of peasants’ output but only putting 5 per cent of their incomes back into the land:

The nobility, who disposed of the necessary means to employ technological improvements, squandered the vast bulk of the extorted surplus, while the peasantry, for whom the deepening of capital was a question of life and death, could seldom accumulate sufficient reserves to take steps in that direction.42

Soil exhaustion became a general phenomenon and led to miserably low crop yields. Braudel found that:

Wherever one looks, from the 15th to the 18th century, the results were disappointing. For every grain sown, the harvest was usually no more than five and sometimes less. As the grain required for the next sowing had to be deducted, four grains were therefore produced for every one sown.43

Nothing like this happened in the world’s other economies. In the early 1900s, the deep, well-cultivated soils of China, Korea and Japan were a source of wonder to American agronomist F H King.44 In the great empires of the East, which had had huge armies, strong peasantries and sophisticated bureaucracies throughout the Middle Ages, merchants were never able to commandeer the agrarian economy as they did in Europe. Instead, general welfare sometimes acquired a major share of state resources, as demonstrated for example by the huge system of canals (which had a large famine-prevention role) constructed over many centuries in imperial China, and the ‘taccavi’ system in India, whereby rulers had a duty to help peasants financially through difficult times.

Within the capitalist polities, subsistence seldom even registered as a possible cause for concern. During the famine and plague years of the mid-1300s, cities including Florence and Milan, in desperation, reduced the tax burden on the peasantry and even initiated half-hearted irrigation schemes, but by this time the damage was done; the peasants were deserting the land and nothing could stop them.45 Immiseration and soil exhaustion gradually turned into a full-blown demographic and ecological crisis, experienced at the time, all over Europe, as a sudden exodus of impoverished peasants from the land and into towns. A dynamic had started that required constant expansion or collapse.

The difficulties became extreme during the ‘little ice age’ – the period from the early 16th till the early 19th centuries, when global temperatures fell by two whole degrees Celsius. Indeed, this has been blamed for Europe’s crisis – but the climate challenge did not affect all areas as badly, if at all. Some places, like Japan (newly unified by the Tokugawa regime), came through it with both environment and people in very much better shape than at the beginning.46

In Europe, the demographic and environmental crisis had begun long before, and continued till long after. By the beginning of the 20th century people were abandoning Europe at a rate of nearly a million a year, making Europe’s exodus the largest mass emigration in history.

AN UNEQUAL SOCIETY IS A DANGEROUS PLACE FOR POWERFUL IDEAS

This puts a different complexion on the traditional account of ‘the rise of the West’, which used to attribute Europe’s sudden expansion to the particular mindset or social structures of Europeans, or even to their higher state of evolutionary development: a view that remained fairly dominant even within living memory.

Deborah Rogers, a Stanford University researcher and now Director of the Initiative for Equality (IfE), looked at the riddle of European expansion from a different angle: given that human societies have been so characteristically and strongly egalitarian over the long run of history, why did unequal ones (and extremely unequal ones at that) end up sweeping the field?

Her team used a computer-modelling approach, which revealed (contrary to expectation) that the takeover of egalitarian societies by unequal ones had nothing to do with superior leadership or organization. Instead, it appeared that unequal societies have a short-term competitive edge over more egalitarian ones because those who take the decisions do not have to suffer their consequences. Rogers writes: ‘unequal societies are better able to survive resource shortages by sequestering mortality in the lower classes.’47 In the longer term, however, these societies can only survive by proliferation – finding fresh populations to bear the burdens they create. She concludes:

Unequal access to resources is destabilizing, and greatly raises the chance of group extinction… which creates incentive to migrate in search of further resources… leading to conquests of the more stable, egalitarian societies – exactly what we see as we look back in history.48

This fits with archeological evidence that, in the past, unequal societies were usually ‘self-extinguishing’. If an unequal society is isolated from its neighbors by forests, mountains or seas, and lacks the technology or resources to overcome them, it exhausts its resources and collapses. But when these obstacles don’t exist, or new technology becomes available that allows them to be overcome, neighboring societies can be made to ‘share the pain’. When these also become destabilized, they can ‘spill over’ in their turn into adjacent lands, and so on.

By the 1400s, intensely unequal city-states and early nation-states in western Europe had already been ‘sequestering mortality in the lower classes’ for about four centuries (as evidenced by their skeletal remains). Large areas of Europe were on the verge of ecological and demographic collapse – but its elites were acquiring new technologies such as firearms and ocean-going ships that allowed them to reach and dominate societies that were further and further away, across mountains, seas and eventually oceans until, finally, the system became global.

Western expansion was the result of a deadly combination: intense inequality, emerging just at a time when human technologies were evolving to a stage where they could become deadly weapons in the hands of unaccountable elites.

From the 11th century onwards, new technologies arrived on the scene like kerosene deliveries to a burning building.

WATER MILLS, AND HOW NEW TECHNOLOGY CAN BE A CURSE

The scene was set for Europe’s descent into extreme inequality in the first centuries of the second millennium, and that period provides a clear example of what should have been good technology falling into the wrong hands, and becoming a curse.

Around the year 1000 there was a sudden proliferation of water mills for grinding corn, and this was examined in detail in 1935 by the historian who inspired Braudel, Marc Bloch.49 Whereas there were only perhaps 200 water mills in England at the time of Alfred the Great (849-899) there were 5,624 at the time of the Domesday Book (1086). In northern France the pattern was similar: 14 mills on one river, the Aube, in the 11th century, 62 in the 12th and over 200 by the early 13th century.50

This looks like a thoroughly enlightened development and had always been presented as such, but Bloch showed that it was quite otherwise. Far from being generous gifts from kindly aristocrats, water mills were imposed on unwilling populations and used as instruments of extraction. Peasants were required to take all the corn they grew to the lord’s water mill for grinding – so that the lord could help himself easily to whatever proportion he considered to be his just share: a much simpler arrangement than sending armed men around from household to household.

Hand mills were outlawed everywhere. Bloch found records of house-to-house searches for illicit mills in the 12th century, and at least one famous insurrection, at St Albans in 1274, which rumbled on until the Peasants’ Revolt in 1381. All the water mills of that period for which records exist were imposed under feudal or monastic auspices.51

One sees just how all those great castles and abbeys came into being. They rose almost literally from the ground as the mill-wheels turned, sucking wealth out of everything and everyone around them. It no longer seems surprising that one of France’s most palatial châteaux, Chenonceaux, on the River Loire, began its life as a water mill.

It appears that hand milling has important nutritional advantages. Modern studies have found that the greater force and heat generated by mechanized milling can destroy nutrients, and more nutrients are lost if you have to grind your grain all in one go and then store it; over 80 per cent of its vitamins can be lost within three days.52 In her book about Ladakh’s peasants, Ancient Futures, Helena Norberg-Hodge says that hand milling may have explained the Ladakhis’ excellent health, despite a diet consisting mainly of barley. Vitamin deficiencies started to appear after the introduction of petrol-powered mills.53

So perhaps the water mill’s introduction even played a part in the decline in stature of ordinary north Europeans (described in the next chapter), which started at just this time.

FIREARMS TAKE A EUROPEAN TURN

There was sharp increase in European inequality between 1500 and 1650. Peasants’ real incomes fell by as much as a half, and selective adoption of new technology played a part here as well. In a much-cited paper published in 1979, the economic historian John Pettengill demonstrated that a very large part of the decline could be explained by the widespread adoption of new, small firearms by the European nobility during these years.54 Hand guns in 1500 were cumbersome items, fired by a glowing fuse or ‘match’; useful in armies but not suitable for a casual demonstration of personal power. Leonardo da Vinci had invented a wheel-lock arrangement in the 1480s, which allowed a gun to be fired just by pressing the trigger; improved versions of this were spreading throughout Europe by the 1520s. Pistols became possible and horse riders could use them. By the mid-1600s cheaper, more efficient flintlocks were becoming common, but they were still far beyond the means of the peasantry.

The power of armed enforcers, militias, or just an individual with a gun, was multiplied with each improvement. Pettengill showed how, as these developments unfolded, rents and taxes on peasants rose by multiples; restrictions on the use of commons were introduced and enforced; peasant rebellions were crushed with greater and greater predictability.

The result in eastern Europe was a wholesale return to serfdom; in the west, the result was an increasing rate of migration from the land to towns (and in some cases, as in England, deportation of surplus population to new colonies in Ireland and then in America), and ‘proletarianization’, as merchant elites learned to harness the new, precarious population through the Verlag or ‘putting out’ system of manufacture.

Pettengill found similar increases in immiseration from Scandinavia to Italy, and from western Spain to Russia. He knew of ‘only two exceptions to this pattern: Venice and the newly industrialized areas of Holland’.

Was this bound to happen, once the principle of firearms had been invented? Things didn’t unfold in this way in other parts of the world. Firearms were well established in China by the 13th century but were not turned into personal weapons. They were adopted in the Arab, Persian and Indian empires by the 15th century, and developed there, but without the appearance of a culture of firearms like the European one. The historian Noel Perrin tells us that Japan acquired its first firearms, a pair of arquebuses, from a Portuguese trader in 1543 – the same year in which a French immigrant ironmaster gave England its first cast-iron cannon.55 Japanese gun enthusiasts improved on these two originals at a furious rate and reduced the cost of a gun from 1,000 to just 2 gold taels. By the end of the 16th century, the Japanese were able to have the kinds of battles among themselves that the Europeans could not manage until the end of the 18th (one of these, the battle of Nagashino, is the centerpiece of Akira Kurosawa’s film Kagemusha, the Shadow Warrior). They then ‘de-invented’ firearms during the long, peaceful period that followed the Tokugawa clan’s final victory in 1600 and lasted until 1868. When the US Commander Perry arrived in 1855 no guns whatsoever were to be seen.

It happens that the Tokugawa period was also a period of great equality in Japan. As the demographic historian Osamu Saito describes it, it was a case of ‘all poor but no paupers’.56 Society was rigidly hierarchical and ferociously punitive but, as Braudel puts it, it ‘bristled with “liberties” like the liberties of medieval Europe behind which one could barricade oneself’.57 Compared with Europe, the gap between rich and poor was minuscule, reflecting a much more equal balance of power. Village self-organization was a force to reckon with. The samurai class (who became government employees after the Tokugawa ascendancy) were often only a little better off than the peasants who, unlike so many ‘modernizing’ European peasants, controlled their own rural industries and paid little tax on the skilled work they produced, and which became regarded as so essentially Japanese. Other historians note that the physical quality of housing and amenities improved immeasurably and ‘when viewed through the lens of life expectancy, Japanese led surprisingly long lives’.58

The environment also recovered. In the earlier period, large parts of Japan had been stripped of timber (in large part for building castles, temples and monuments). Despite a doubling or even tripling of Japan’s population between 1600 and 1700,59 deforestation was permanently reversed from around 1670, apparently through community initiatives as well as government ones.60 Japan still has a surprising amount of forest for such a densely populated country. In 1993, 63 per cent of its land area was covered in closed forest.61

From a purely functional and environmentalist point of view, Japan seems to support a saying of the epidemiologist and equality campaigner Richard Wilkinson that, to a certain extent, ‘it doesn’t matter how you get your greater equality, as long as you get it’.62

1 Stéphane Hessel, Time for Outrage, Quartet Books, 2010.

2 InterOccupy obituary for Hessel, nin.tl/InterOccupyonHessel Accessed 11 Aug 2014.

3 Neal Ascherson, review of Ian Buruma’s Year Zero, The Guardian, 12 Oct 2013. See also Gerry Cordon, nin.tl/AschersonEurope Accessed 11 April, 2014.

4 Wilfred R Bion, Experiences in groups, and other papers, Basic Books, 1961.

5 Donald Woods Winnicott, Playing and Reality, Tavistock, 1971.

6 Theodor W Adorno, The Authoritarian Personality, Harper, 1950.

7 Stanley Milgram, Obedience to Authority: an experimental view, Harper & Row, 1974.

8 For a comprehensive update on these matters, see HM Ravven, The Self Beyond Itself, New Press, 2013.

9 Goldin & Margo, ‘The Great Compression’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107, Feb 1992, pp 1-34.

10 Timothy Noah, The great divergence, Bloomsbury, 2012.

11 Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Harvard University Press, 2014, p 499.

12 Ibid, p 505, note 33.

13 Rob Rooke, ‘A Brief Socialist History of the Automobile’, Links, 19 May 2009, links.org.au/node/423

14 G Gorodetsky, ed, The Maisky diaries: red ambassador to the Court of St James’s, 1932-1943. Yale University Press, 2015, p 475.

15 Caroline Moorehead, Village of secrets: defying the Nazis in Vichy France, Vintage, 2015.

16 Richard Wilkinson, The Impact of Inequality, Routledge, 2005, pp 208 & 302.

17 World Bank, The East Asian miracle: economic growth and public policy, Oxford University Press, 1993.

18 Lecture by Kristen Nygaard, nin.tl/Nygaardlecture

19 Kristen Nygaard, ‘Those Were the Days’? Or ‘Heroic Times Are Here Again’?, Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 1996, aisel.aisnet.org/sjis/vol8/iss2/6

20 Robert Howard, ‘Utopia: where workers craft new technology’, in Perspectives on the Computer Revolution, ed Liam Bannon & Zenon Pylyshin, Ablex, 1989.

21 Industrial Structure Council report, quoted by T Morris-Suzuki, Beyond Computopia: Information, Automation and Democracy in Japan, Kegan Paul, 1988, p 11.

22 Jim Sidanius & Felicia Pratto, Social dominance: an intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression, Cambridge University Press, 1999.

23 Vladimir Popov, ‘Why the West Became Rich before China and Why China Has Been Catching Up with the West since 1949’, New Economic School, Moscow, 2009, nin.tl/PopovChina

24 AY Abul-Magd, ‘Wealth Distribution in an Ancient Egyptian Society’, Physical Review E, vol 66, 2002.

25 G Alfani, ‘Wealth inequalities and population dynamics in early modern northern Italy.’ Journal of Interdisciplinary History xl, no 4, Spring 2010, 513–49

26 Prasannan Parthasarathi, Why Europe grew rich and Asia did not: global economic divergence, 1600-1850, Cambridge University Press, 2011.

27 D Held & A Kaya, Global inequality: patterns and explanations, Polity, 2007, p 84.

28 Christoph Lakner, Branko Milanovic, and World Bank, Global Income Distribution From the Fall of the Berlin Wall to the Great Recession, World Bank, 2013.

29 Fernand Braudel, The Wheels of Commerce, Collins, 1979, p 190.

30 Ibid, p 192.

31 Ibid, p 405.

32 ‘Steve Jobs thrives on dividend income’, Seeking Alpha, Jan 2010, nin.tl/SteveJobsdivis

33 David Barboza, ‘Supply chain for iPhone highlights costs in China’, New York Times, 5 July 2010.

34 Fernand Braudel, Afterthoughts on Material Civilization and Capitalism, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977, p 107; see also Braudel, Wheels op cit.

35 Maria Mies, Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale, Zed, 1998.

36 Eric H Mielants, The Origins of Capitalism and the ‘Rise of the West’, Temple University Press, 2007, p 155.

37 Ibid, p 160.

38 Peter Spufford, Money and Its Use in Medieval Europe, Cambridge University Press, 1988, p 247.

39 V Groebner, M Kyburz & J Peck, Who are you?: identification, deception, and surveillance in early modern Europe, Zone Books, 2007.

40 C Freeland, Plutocrats: The New Golden Age, Doubleday Canada, 2012.

41 E Christiansen, The Northern Crusades, Penguin, 1997, p 42.

42 C Lis & H Soly, Poverty and Capitalism in Pre-Industrial Europe, Harvester Press, 1982, p 28.

43 Fernand Braudel, The Structure of Everyday Life, University of California Press, 1992, p 120.

44 FH King, Farmers of forty centuries; or, Permanent agriculture in China, Korea and Japan, Mrs FH King, Madison, Wisconsin, 1911.

45 Spufford, op cit, pp 105-106.

46 Geoffrey Parker, Global Crisis, Yale University Press, 2013, pp 484-508.

47 Deborah S Rogers, Omkar Deshpande & Marcus W Feldman, ‘The Spread of Inequality’, PloS One 6, no 9, 2011.

48 Deborah Rogers, ‘Inequality: why egalitarian societies died out’, New Scientist, 30 July 2012.

49 Marc Bloch, ‘The Advent and Triumph of The Water Mill’, in J E Anderson (ed) Land and Work in Medieval Europe: Selected Papers by Marc Bloch, New York, 1969, pp 136-68.

50 Calum Roberts, The Unnatural History of the Sea, Shearwater Books/Island Press, 2007, p 23; citing RC Hoffman, ‘Economic Development and aquatic ecosystems in mediaeval Europe’, American Historical Review, 101:630-669.

51 Stephen A Marglin, ‘What Do Bosses Do?’, The Review of Radical Political Economics 6, no 2, Summer 1974, 60–112. p 104; citing Bloch/Anderson Land and Work in Medieval Europe, op cit.

52 A website selling modern hand mills for the kitchen tells us that ‘Commercial milling removes nearly 30% of the most nutritious parts of the whole grain. Within 72 hours, whole grain flour has lost over 80% of most vitamins. Mold and bacteria also quickly combine to further reduce nutrients and taste. The wheatgerm oil quickly becomes rancid, leaving the flour tasting flat at first, and then bitter.’ skippygrainmills.com.au/faq.htm

53 Ladakh Project: localfutures.org/ladakh-project

54 John S Pettengill, ‘The Impact of Military Technology on European Income Distribution’, Journal of Interdisciplinary History 10, no 2, 1979, 201, doi:10.2307/203334.

55 N Perrin, Giving Up the Gun, Nonpareil Books/D R Godine, 1979.

56 O Saito, ‘All Poor but No Paupers’, Leverhulme Lectures, University of Cambridge, 2010.

57 Braudel, Wheels of Commerce, op cit, p 590.

58 WM Tsutsui, A Companion to Japanese History, Wiley, 2009; see also Susan Hanley, Everyday Things in Premodern Japan, University of California Press, 1999.

59 Parker, op cit, p xvi.

60 Gerald Marten, ‘Japan – How Japan Saved Its Forests’, The EcoTipping Points Project, June 2005, nin.tl/Japansilviculture

61 Marcus Colchester & Larry Lohmann, The Struggle for Land and the Fate of the Forests, World Rainforest Movement, 1993, p. 21.

62 Richard Wilkinson, various presentations including (online) ‘The Levelling Spirit’, Communities in Control Conference, Melbourne, 1 June 2010, nin.tl/Wilkinsonleveling