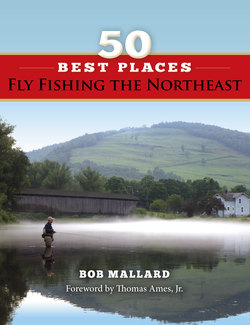

Читать книгу 50 Best Places Fly Fishing the Northeast - Bob Mallard - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеbeen subject to challenge, interpretation, and subsequent revision. Most fly fishers believe they have more legal rights in regard to access to water than they actually do.

Some water in the Northeast is public, some is not. Some water on public land is open to anglers, some is not. Some water on private land is open to anglers, some is not. Some of the fishing allowed on private land is voluntary, some is not. It is imperative that anglers understand the laws governing trespass to avoid conflicts with landowners and law enforcement.

Maine’s Great Ponds Act guarantees access to waters larger than 10 acres for the purpose of fishing. This can, however, be restricted to walk-in and fly-in. Many states have navigable water laws associated with rivers and streams. The definition of navigable varies from state to state. This allows anglers access by foot or boat, as long as they enter on public property, and stay below the high-water mark. In some states, however, if the landowner owns both banks of the stream, he or she also owns the riverbed, and you cannot wade or even drop anchor without permission.

Unfortunately, as in many other parts of the country, some quality water is not open to the public. In many cases these are nonnavigable streams or small ponds. Some private land in the Northeast is restricted to pay-to-fish or even membership in exclusive clubs. While this situation is primarily found in Pennsylvania, it is not exclusive to Pennsylvania.

Great Fisheries

All fisheries go through peaks and valleys. Events such as floods, droughts, heatwaves, and harsh winters can all affect a fishery from one year to the next. Then there are the parasites and diseases that can change a fishery for decades—or longer. Invasive plants and fish can severely impact a fishery as well.

Regulatory changes usually—but not always—impact fisheries in a positive way. Eliminating the use of bait reduces harvest, and incidental mortality, and can help stop the spread of invasive minnows. Catch-and-release, slot limits, and creel reductions all result in fewer fish being harvested.

Fisheries can be quite resilient, especially great ones. They often respond well—and faster than most expect—to changes such as stricter regulations, habitat restoration, and reclamation. They can also rebound from what might look like a hopeless situation. One need look no further than the Madison River in Montana, which, after losing 90 percent of its wild rainbow trout at the peak of the whirling disease catastrophe, has once again become a marquee fishery.

While one fishery is down, another may be up. All fisheries have good years and bad years. Some fisheries can stay down

for a decade, and then seemingly overnight rebound to the point where they were before they crashed. Some fisheries experience explosions for reasons no one quite understands. Some keep chugging along year after year, with little if any real noticeable change.

Striped bass populations are famous for peaks and valleys. After hitting rock bottom a few decades ago, the Northeast striper fishery rebounded to a point where people were coming from all over the country to enjoy it. But recent changes have some concerned again.

I suspect that all the fisheries that are currently down will eventually rebound. They are great fisheries, and great fisheries usually do come back. I also suspect some others will fall on hard times in the years to come. But they too will most likely come back. And in many cases, bad fishing on a great fishery is better than great fishing on a bad fishery.

The List

This book is about great fisheries, those that have been great for many years and will hopefully be great for years to come. I give consideration to infrastructure—lodging, food, boat launches, fly shops, guides, and so on. This makes a great fishery even better. I also give consideration to regulations, such as artificial lures only, fly fishing only, catch-and-release, and slot limits, which all help to improve the overall experience.

By far, the biggest challenge in writing this book was coming up with the list of waters. If the list was not solid, the book would suffer. There could be no glaring omissions. But there should be some surprises—regardless of whom I might upset.

I had to look at the waters in an objective and unbiased manner. This meant potentially leaving out waters I wanted to cover for professional reasons. In some cases, it meant omitting waters where friends, peers, and associates had a financial investment. In other cases, I would be directing anglers to a fishery that some people I know would rather I did not.

Each fishery had to be covered in a way that did it justice within the space available. To write about the Swift River in Massachusetts, and not write about the river below Route 9, would be a disservice at best. Conversely, trying to cover rivers as large and diverse as the Kennebec in Maine in just a few pages would present a challenge.

This book is about fly fishing. While fly fishing is often associated with trout, it is not exclusive to trout. While trout are often associated with moving water, they are not exclusive to moving water. As a result, this book is not exclusively about trout or moving water. It is, however, primarily about trout and moving water, as this is often the