Читать книгу Conspiracy of Secrets - Bobbie Neate - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

EARLY DAYS

ОглавлениеOn my last visit to see my mum she had been on great form. Nobody would ever have guessed that she was eighty-nine years old. She never needed to visit the doctor and her sharp brain had not dulled. She was still able to make her hair look as if she had just returned from the hairdressers but now she favoured a new softer less back combed style. A bouffant hairstyle had been my mother’s trademark but she had not achieved this without a great deal of effort. She never went to bed before one in the morning. Stepfather never allowed her go to bed before he did. So at midnight and often much later, I would find her sitting on her bedroom stool in front of her three-panelled mirror with the radio blaring out any kind of music. She vigorously brushed her hair to remove the hairspray. Then carefully she combed sections onto her homemade cotton wool rollers. Her backcombed hairstyle was held in position by spray for ‘hard to hold’ hair. In the days of Grand Prix racing Louis insisted she backcomb her hair to silly heights to fool people that she was tall. Over the years she increased the amount of lacquer with ‘extra firm hold’ until even a strong breeze left her hair unscathed. Stepfather forbade us children to touch her hair but if I accidentally brushed it, it felt like a rough netted bag with a squishy inside.

Shoes also helped Mum disguise her lack of height. She wore the highest shoes she could find with the most tapered heels. She could wear them all day and when she became fond of gardening she even worked on her herbaceous beds in them! The leather tip on her highest stiletto shoes might only last one or possibly two outings. Her taste in shoes allowed for some amusing family tales: frequently her stiletto was caught in a drain, or a crack in the pavement or worse still a manhole cover. She had too many narrow escapes to ever agree to stand on an escalator.

As we became older we realised that Stepfather was able to whip Mum up into an emotional state. Occasionally something would bug her and she would sound tense. Each time we discovered that Stepfather had been winding her up. It worried us but there was nothing we could do. Then Stepfather demanded we buy her more and more costly presents for her birthdays. It was a powerful tactic.

As the couple grew older we began to be anxious about what might happen in the future. However, when she became worried about the state of her finances a warning bell rang inside my head. I decided that her trusted accountant, Mr L, ought to know. As I talked privately to the man I had met many times before I surprised myself by blurting out that I had suspicions that my mother’s money might be going missing. I even surprised myself by asking this adviser if Stepfather could be the subject of blackmail. His reply bowled me over as he said, ‘I’ve learned over the years to rather like Louis.’

Why did he say this? This man was Mum’s trusted guru and was acting for her. So, rather than act on my vague suspicions, the accountant ignored my warnings.

I tried to forget about the meeting. I was powerless.

We had all individually pondered, when we were children, over Stepfather’s behaviour with our mother, but none of us had noticed how odd it was. It was our partners who appeared fascinated as to how and why our lovely mother had married such a problematical man while we had accepted the facts that no friends called on our sociable mother and she never went out on her own. Sporadically, sometimes over a glass of wine, our spouses encouraged us to conjecture what Stepfather had done in his earlier life. We had not thought him worthy of speculation.

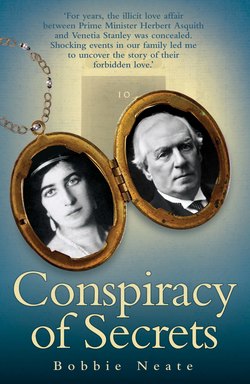

There was a memorable time when I first suggested that perhaps his father had been an MP. ‘Why do you think that?’ asked my siblings. I had no absolute answer but they accepted my justification. ‘He seems to know so many politicians and people in that field,’ I replied. My siblings agreed it was possible and even half-heartedly searched for MPs with the surname Stanley. There had been a number of ‘Stanley’ MPs, and I found a photograph of one called Arthur, but none seemed of the right age, and, as we were not particularly interested, we never continued our search. One day, much later, I had turned to a historical text and spotted a photograph of Prime Minister Asquith. It had made an immediate impact on me. But, as I had no real reason to enquire further, I left the book unread and tried to forget the unmistakable likeness.

In those early days, golf and steeplechasing were Stepfather’s preferred interests, not Formula One cars. Mum eventually persuaded him to enjoy the motor races and when I was just six she took us children along too. So even as a very young child I visited the rarefied atmosphere of the racing paddock and became fascinated by the huge complicated engines. It is the noise of the sport that has left its legacy with me. Even now when I hear a souped up car in the distance I relish the noisy power of the engines reverberations. Every time my ears pick up the sounds I am reminded of the powerful roar of the V16 BRM and my childhood.

I am not alone. Motor racing enthusiasts still reminisce about the pitch and volume of the BRM’s 16-cylinder scream. Motor pilots of that generation recall that the engine roared its power with such ferocity its noise distracted even the most seasoned drivers as they waited for the flag to drop.

How did my mother come to be so involved in a Formula One racing car in the days when women rarely had careers?

Two enthusiastic and idealistic men called Raymond Mays and Peter Berthon wanted to emulate the might of the partially state-funded German motorcars of Auto Union and Mercedes-Benz, which had dominated racing up to 1940. So after the war the British Racing Motor Company was created. Its racing cars were to be known by the initials BRM. With great national excitement the first model, called the V16, was unveiled later in the year. Everybody agreed that it was handsome and hugely powerful. However, raising enough money in austere post-war Britain was always to prove a problem. Mays decided to contact companies involved in the motor trade. Rubery Owen, our family’s firm, was one of his targets. My two uncles took the bait alongside a large number of other motoring companies.

However, too many people, too soon, had wanted to see the car race with too little money. After much national hype, the first all-British Grand Prix car painted in patriotic Brunswick Green rolled onto the Silverstone grid for a demonstration run on 13 May 1950. The shrill V16 exhaust excited the crowds. But the world’s press wanted the car to race, so in August of that year the Daily Express funded a Silverstone race. The paper hyped up much public interest in the patriotic car. All the engines roared while the drivers waited for the flag to drop to announce the start of the first heat. All British eyes were on Raymond Sommer, perched in the cockpit of the BRM. To add to the tension, the royals looked on from the grandstand. The starter’s flag fell and the race began. The BRM lurched forward to start its great career. But calamity struck! The drive shaft broke and the huge machine failed to move further than a few metres. To the humiliation of all involved, the V16’s race was over before it had begun. The crowd in the grandstand jeered and catcalled the mechanics when they appeared from the pits to push the car back to the paddock. The British press condemned the car’s dismal failure. One paper headlined its front page with FLOP and another lined up the letters with BRM calling it a BLOOMING ROTTEN MOTOR!

I can remember Mum hiding her eyes in shame as she told me the story of the car with its chassis made by her family company, failing to leave the grid. Even though they were only part of a consortium of companies, she and her brothers had felt the nation’s shame on their shoulders.

After more outings that demonstrated that the cars were too unreliable to win races, the BRM Trust was disbanded and put up for sale. My Uncle Alfred and to a lesser degree my Uncle Ernest retained faith in the car’s potential, so the family firm, having recently expanded to be known as the Owen Organisation, bought BRM. It was a rash decision.

The modern industry of sleek, sponsor-endorsed, computer designed, semi-automatic cars, racing on pristine tracks with every possible facility, bears no resemblance to the fun loving sport of the fifties recovering from the traumas of a world war. It is now a billion dollar business for the ever-expanding racing teams and has little to do with a ‘sport’ in the original sense of the word.

In the fifties and sixties motor racing was colourful and exciting, full of dash, verve and characters. The rash youths of the day, frequently the sons of the world’s wealthiest families drove for pleasure, often recklessly and at breakneck speeds. There was little or no sponsorship with many of the cars financed on a shoestring. Mechanics from each team were friends and lent each other vital tools. In those times each part of the country had its own racing tracks; most were nothing more than old wartime airfields converted to form a circle. Safety for both drivers and spectators was rudimentary or in some cases nonexistent. Circuits used farmers’ straw bales to line the track or a tricky chicane. Their combustibility caused many unnecessary fires. Trees and telegraph poles were left to stand beside the track without a thought of their treacherous ability to kill.

Post-war cars were powerful. Even in the fifties racing motors could reach the type of speeds Formula One cars race today. But race technology was in its infancy. Engineers tried to apply lessons learned in the war from the performance of jet engines to racing cars. However the rest of the mechanical workings of the cars had not developed in line with the sheer pace of the engines.

Fire-protective clothes had not been invented so the drivers wore ordinary cotton overalls. Their gloves might have leather palms but were often string-backed and bought off the peg. They may have worn soft-soled shoes but there was nothing to protect them from the scorching heat of the cockpit. When I look at old photographs I realise their hard-hat style helmets provided little protection. As they sat high up, almost out of the vehicle, I loved to watch them change gear and struggle with the vibrating steering wheel. If the car should turn over they had no roll bars to protect their heads and no seatbelts to hold them in on the bouncy tracks. The only way of communicating between engineer and driver was by a metal board held out by a mechanic for the driver to read a coded message as he screamed past the pit lane.

Each car represented a country and they were painted accordingly: the German cars which had dominated racing prior to the war were silver, the French cars were blue, the Dutch orange, the Italians had their red Ferrari and Maserati, and the British cars were green.

Stepfather hated being an appendage. That’s why he hated motor racing in those early days. BRM was part of my mother’s family company and it was her hobby. He didn’t want anything to do with it.

It seemed incongruous that Stepfather did not drive – especially later, when he stealthily eased himself into becoming joint managing director of the BRM racing team with my mother. We knew he could drive, but he never did.

I hardly dare recall the terror of the afternoon when we, as children, had goaded him to prove to us he could drive. I was very small and he had driven like a maniac through the villages of Cambridgeshire. It was so terrifying we dared talk about it only once and that was in earnest whispers. We never teased him again about his rejection of the driving seat – we had learned our lesson. But this did not stop him repeatedly telling us stories of his adventures in fast-moving cars. His favourite tale was about driving his Bentley through the London backstreets, racing and betting with others as to who might reach the Dorchester first. His stories never made sense. Why did he have a Bentley? If he could drive, why demand that my mother do all the driving? He was a man who always liked to show off, so why did he ask his wife to drive in prestigious situations in front of Formula One world champions? I even remember sloping around in the back of Mum’s Isis with Jack Brabham. He was beside me and leant forward over the seatbacks earnestly listening to the conversation from the front. Mum drove while Louis took the front passenger seat. He would not allow even that year’s world champion to take his seat.

Could Stepfather have been banned from driving? It all added to the dark mystery of the man. But there were so many strange things about this stepfather of mine. He had huge amounts of energy and anybody who could not keep up with him was always referred to as ‘a wimp’. Nobody was allowed to say they were tired. He had no patience for anybody who might be frail or infirm and he could change in seconds from a jolly mood to a persistently black one.

My earliest memory of motor racing was the race for the Silver City Trophy at Snetterton. It was the poor relation to the more prestigious Brands Hatch, Silverstone and Goodwood, but it was the nearest of the five big circuits to Cambridge and we supported the track whenever the BRM was entered.

The day did not start well. Our tickets did not arrive in the early-morning post, so we had to wait for the late-morning delivery, hoping for our entry passes and parking discs. Tempers were frayed before we left the house. Once again Mum would be in the driving seat. As we sat in the traffic jam outside the track we heard the menacing machines leap away from the distant grid. We had missed the start and our automatic right to enter the Paddocks. This led to a most embarrassing altercation outside the main gates. Stepfather pointed his thick fingers in a menacing manner at a group of men and demanded that we be allowed to enter. But he was not well known at that time and they refused us entry.

‘If you won’t let the car in, get your snot-ridden youngster with his acne spots to run to the BRM pits to collect the tickets for us,’ he snapped, while Mum shuffled uncomfortably in the driver’s seat, leaning over the gearstick and trying to smile at the steward but to no avail. For once there was no option but for Mum and Stepfather to split up. My mother and I were directed to park in a desolate area on the furthest side of the track.

The route back to the paddock lay along a tufted grass path running alongside viewing banks, often so high they blocked my view of the racetrack. As a group of cars roared past I scrambled up one of the hillocks to see if I could spot the familiar green bonnet of the BRM. The noise was thunderous as they first braked and then accelerated around the corners. At the next bank Mum joined me, slithering unceremoniously in her heels. I steadied her, as a tightly packed group of cars roared past. In the bunch were two BRMs tussling with a Cooper. We squeezed each other’s hand.

The finish was perfect: the cars accelerated for the line and Ron Flockhart took the chequered flag. The P25 BRM had won the Silver City Trophy. Flockhart, a dashing Scotsman, grinned from ear to ear as he struggled to undo the chinstrap of his helmet. He wiped his hands on his sweat-stained cotton overalls and there were handshakes all round. To my delight he insisted on shaking my hand. Even Stepfather clapped everybody on the back and spoke in loud tones. I remember little else of the day, but winning had been intoxicating. The joy was infectious. Other drivers, their mechanics and team managers all made their way to congratulate the BRM team. I became entranced.

For one single hour at that racetrack, Stepfather was not by my mother’s side. I was her only companion and she enveloped me in her new world. Before my eyes, my mum became the impassioned supporter of a green single-seater racing car in which daredevil men, in battered helmets, drove around circular roads with tight bends at death-defying speeds. After all the disappointments of the past years I understood that BRM could win races!

As years went by, tickets became a source of fun for Louis. He always wanted get to more prestigious places on the grid where he would normally be barred. So he brazenly forged himself a counterfeit fancy arm-badge to deceive all the foreign authorities, and, when travelling abroad, he insisted on an opulent vehicle that would impress the many gatekeepers who had previously wanted to keep him at bay. Once Louis found a German chauffeur who was willing to use his huge hired Mercedes as a battering ram through the crowds and past the lines of irate marshals in his own country, he never let him go. Later, this chauffeur was driving him down a series of Alpine hairpin bends when they met a bus full of schoolchildren. The bulky Mercedes was unable to squeeze through the gap, and both drivers refused to move. After an altercation, Louis got out of the limousine and into the bus. He took the keys out of the ignition and threw them down the ravine, leaving a bus full of children stranded on a mountainside.

Most of the major races were held in the school holidays or on bank holidays. I never tired of watching the BRMs being unloaded from their transporters and pushed around the paddock and eagerly waited for them to roar into life. The cars had to be ‘push’ started so every time a motor needed to be fired up two strong mechanics stood behind the machine and shoved with all their might for ten or twenty yards until the momentum allowed the driver to ignite the sparks. The last minute trouble-strewn hasty scrambles to overcome mechanical gremlins were all part of the fun of racing.

I remember Silverstone circuit as little more than a windswept airfield with basic facilities. The paddock and pits were located on the island of land inside the circuit and so each year the organisers had to build a temporary access bridge to provide pedestrians access to each side of the track. This was the fifties and the bridge was just made out of scaffold poles and planks. As each car roared down the home straight the ill-equipped bridge shook terrifyingly.

Being allowed into the pits never lost its thrill. It was where everything happened. They were just narrow concrete bays with no facilities but once practice started they became full of life. From my corner I watched the race mechanics carry to and fro their metal toolboxes crammed full of essential implements. In the less important races the mechanics allowed me to find the metal number tiles that were slotted into the drivers’ message boards.

I probably enjoyed the thrill of being close to complicated engines more at Oulton Park circuit than anywhere else. It was not a championship course and everybody was more relaxed, as the races were treated as experimental outings. Because the circuit was in Cheshire, we usually stayed up North, in either Chester or Liverpool, the two cities Stepfather loved. In fact, looking back, I would say he changed character when we in the vicinity of the Wirral. He was more relaxed, took control of navigation and was always trying to tell Mum some story about the history of the towns.

The Adelphi Hotel in the heart of Liverpool was no treat for youngsters. It was built of large sludge-coloured stones and had grey-coated commissionaires who attended its revolving doors with a bored disposition. The hall gave me the impression that only the staid and serious were welcome. Stepfather tried his best to be on cordial terms with the local staff and he made it quite obvious he wanted to share his knowledge of the city with them. Sometimes while we were up there I recognised a hint of a Merseyside accent appear through his plummy voice. Even though he was secretive about his childhood, once up North, he loosened up and admitted that Cheshire was his home county and he loved the city of Liverpool because he was brought up in a small seaside town, Hoylake, on the other side of the Mersey. Liverpool Football Club was his passion and at every opportunity he anxiously looked for their results on news agency’s tickertape. When we were in the area he usually wanted to stay a night at Lytham St Annes, another seaside town with a famous links golf course.

However, it was at Aintree trackside that we heard him brag to the BRM team, ‘Well, of course, my family is related to the Stanleys of Liverpool. Stanley Park is named after them and the Earl of Derby is a relative.’ The boast seemed very odd. Why had he chosen to tell strangers about his family and not us? So when he was in a good humour I asked, ‘So who were the Stanleys of Liverpool?’ To my utter surprise his mood changed dramatically.

‘You know nothing,’ he snapped, trying to finish the conversation.

‘Yes, but I want to learn – who were the famous Stanleys?’

‘They owned most of Cheshire.’

I felt anxious, as Mum had left the room, but my childish curiosity was too great, and once started I was not going to let go, so I continued with my questioning.

‘And the Earl of Derby, who was he?’

‘He was rich and famous, a politician, owned many racehorses and swathes of land in Liverpool.’

But that was as far as I got because Mum reappeared. I had got him exasperated and he now had a good excuse to send me away with a flea in my ear, telling my mother I deserved a good hiding. As always, I never discussed my questioning with my siblings. We were cultivated not to. But his behaviour did not stop me thinking. Why did he have no relatives other than the two women who lived in our house? If his family were so well known, why didn’t he boast about them? He never stopped crowing about knowing celebrities, so why didn’t he show off about his family? Once, I was taken out of school (he was always trying to persuade Mum to do this because my schooling limited their movements) and I joined them for the famous Aintree steeplechase. On the night before the horse race I had been allowed to stay up to dinner because I was frightened of my drab, dark hotel bedroom, and I sat and watched as Stepfather romantically took Mum off to the dance floor. When I returned to Aintree later that year it intrigued me that I had previously seen the magnificent jumpers go anticlockwise while the racing cars went clockwise on the same piece of land.

An earlier meeting at Aintree motor circuit is etched in my memory because of its ironical nature. On that day Stepfather risked all our lives, but years later he became well-known in his fight to improve motor racing safety.

Mum had dragged Stepfather along and he had bought a couple of Leica cameras with all the accompanying paraphernalia: light meters, holdalls, hundreds of rolls of fast film. He took his shooting-stick on which he precariously perched his huge frame. Over the years the metal frame had became so cluttered with sporting entrance tickets that the seat refused to close. On the first practice day he marched my siblings and myself round the course, where he stopped at various places. He sat for hours on the tiny seat, absorbed with the viewfinder of his Leica, practising moving the camera in synchronisation with the car as it flashed by.

During the afternoon practice session he would want to be at a position near the track, where there were no spectators to disturb the swing of his camera. As the cars started to appear for practice, we walked around the course and based ourselves at the end of the Sefton Straight near the Melling Road. In front of us were some rusting poles, bending in unison, when the brisk wind blew across the undulating land.

I jumped out of my skin when the first car came hurtling towards us. I tried to make my legs run for my life but the shrieking of the tyres and the engine cackling transfixed me. I closed my eyes, as the driver appeared to head straight for me and thrashed with the gearstick. After he had disappeared around the double-twisted turn, I turned to find Mum, equally terrified, pulling at Stepfather’s jacket sleeve.

‘We can’t stop here, we’re right in their path. I have to take the children to safety before another car comes.’

‘You’re my wife. You’re not going anywhere without me.’

‘I think the children are frightened and there’s nothing to stop the cars coming straight into us.’

‘Don’t be wimps,’ he shouted at us, trying to be heard above the noise of the next car approaching. ‘This is an ideal place for photographs of the cars in action.’ The noise abated and he rasped in his usual way: ‘Come on, darling, there’s nothing to fear, they’re just making a lot of noise. You’re not taking the children away. We’re watching expert drivers here. They know what they’re doing.’

Mum made more protestations, but all he said was, ‘There is this protective line of poles in front of us. Come on. You’ll soon get used to it.’ He was clearly enjoying himself. He turned to me and said, ‘This is something to tell your friends about at your primary school.’ How little he knew me! I rarely told any of my friends about my home life.

As the next car stormed towards us, I noticed the driver had difficulty controlling the rear wheels as the back of the car swayed into the chicane. I gripped Mum’s hand tightly– it was cold.

She tried one more time to lift her voice above the scream of the next car: ‘I’m sure this is far too dangerous for us all…’

‘Don’t be silly, dear, this is fine,’ Stepfather replied, not lifting his head from the viewfinder. ‘You’re getting an amazing view from here. You’ll soon get used to the cars coming straight for us.’

In the silences, I listened for the distant rumble of the next car as I searched the horizon for what appeared to be a tiny black fly that climbed the hump, before it came bearing down on us at over one hundred and eighty miles per hour. I grimaced each time, but I no longer closed my eyes, as I was fascinated by the cars, often with one or more of their wheels off the ground.

From a distance all the cars appeared to be the same colour and shape as they sped towards us, and I could only identify individual cars when they were upon us.

Mum and I felt more reassured when we recognised the BRM was out on the circuit with Harry Schell, our charismatic driver, at the wheel. Stepfather continued to concentrate on his photography as we watched our hero find the last possible braking point before drifting through the double bend.

Mum, with stopwatch in hand, predicted when the American would appear over the brow of the hill. It seemed less alarming now we had the BRM to watch. At the allotted time I scanned the horizon for his car. Then, there he was, the uneven surface jostling him from side to side as the car bounced up and down. As he approached, I anticipated the noise of the jangling gears and screaming brakes but I did not expect the gesture: Harry raised his gloved right hand and gave us a big wave!

‘Did you see that?’ I yelled over the screech of the departing brakes.

Mum was as amazed as I was. Stepfather had missed the excitement as his capacious nose was still pressed tight into the sights of his camera.

The lap time of one minute thirty seconds appeared more like one and a half hours as I waited for Schell to reach the top of the small incline again. Finally there he was, bearing down on us, this time I was ready with my hands in the air. As more cars joined the practice session the noise became continuous, so conversation was only possible during brief pauses between cars. The pungent aroma of the shredding tyres hung in the air and I could taste the spent fuel. Finally the session was over and the track was quiet. My legs were like jelly. My mother, obviously relieved, was full of chatter.

‘Oh, Harry Schell is such good fun, isn’t he?’ she chirped. We all agreed. ‘Fancy having the time, on that corner, to give us a wave!’

Back in the paddock, Harry was grinning, happy with his practice times for the day. Mum congratulated him, ‘That time is brilliant for the first day. Fancy having the time to wave at us on the Sefton chicane – the fleas [a term she liked to use for us children] really enjoyed that. You’ve made their day; they can’t stop talking about it.’

‘Oh, that’s all part of the fun,’ he replied, ‘but I was also trying to warn you. That’s a treacherous position to watch; if any of us had lost control, like a car did last year, we would have ploughed straight into you.’

Suddenly Stepfather had slunk away. Mum stuttered, ‘But there’s those iron protective railings…’

‘They’d fall like a pack of cards. That’s not any protection for cars, that’s for the horses. They wouldn’t stop a Hillman Minx at ten miles an hour.’

Two further stories concerning Aintree race track show Stepfather’s persuasive powers in the city he had loved as a little boy. There had been a last minute disaster (BRM was good at late night dramas) and the mechanics who had already worked through one night, were facing the prospect of doing so the following night. Mum felt sorry for them so asked Stepfather to do something to help. He was in home territory and was on good form so he found the local beat policeman. Then he cajoled this neighbourhood ‘Bobby’ to unceremoniously knock up the local publican and demand he provide beers for the BRM mechanics at two in the morning!

The other story was on the morning of the British Grand Prix. Unusually Stepfather had gone out on his own, visiting some of his old haunts. He was late returning and Mum fretted wondering how they were going to get to the track in time. He walked out of the Adelphi Hotel and to my mother’s utter dismay ‘hailed’ a police car. He presumptuously told the local traffic cops that he was urgently needed at the circuit. Needless to say the local coppers agreed to give my mother’s car a police escort. The persuasive powers of this most extraordinary man had worked once again.

After our experience at the end of the Melling Straight we never watched from unprotected corners again but motor racing in those days was lethal. In those days drivers died. It was a common experience for those you knew to die or be injured so horrifically they never raced again.

Wolfgang Von Trips died before Stepfather became involved in safety – he helped fight the track authorities to make circuits safer and organised with others the provision of the first fully equipped mobile hospital for drivers – and his death made a big impact on me. This German was one of my favourite characters, because, alongside his dashing good looks, he made a point of talking with me when I was only very young. He never drove for BRM but wanted to keep his options open.

In 1961 he demonstrated that he was a top-flight driver and was leading in the championship points table. All he had to do was to win the Italian Grand Prix and he would be named as world champion. It was lucky for me that I did not attend, because disaster struck. At full stretch his sizzling red Ferrari was hit by another car. The momentum of the crash shoved his Ferrari up a steep bank and into a group of spectators. Fourteen of them were killed along with von Trips, known as the ‘uncrowned world champion’. His death was poignant for us all.

From then on my mother lost more nervous energy every time BRM raced. And, whether we had won or lost, she would exclaim, ‘Well, thank goodness the race is finally over.’ We all knew what she meant and after each new death her comment took on a new poignancy.

Years later, after I had left home, my mother experienced two traumatic deaths in one year. First there was Pedro Rodriguez, an attractive Mexican who had proved a wonderful tonic for BRM, driving superbly at a time when team morale was low. But disaster struck in 1971, when he was injured in a sports-car race in France. All contracts in the late sixties included a clause that forbade drivers to compete in races other than Formula One unless they sought permission. When we first heard of his accident we discussed why Rodriguez had risked driving in such a minor meeting without seeking authorisation, while Stepfather started to compose Pedro’s ticking-off. But a few hours later we learned he had died. From that moment my mother began to emotionally pull out of the sport. It was not just the grief but also the huge disappointment. After a lean time things had been looking up and now her hopes were dashed. She also had a difficult diplomatic time, as Pedro had a wife in one continent and a mistress in another.

My mother’s greatest fear had always been that a driver should die in a BRM. It was not long after Pedro’s death that the inevitable happened. Later that year, Jo Siffert, the moustached Swiss driver, hit a bank in a minor race at Brands Hatch. He suffered only a broken leg but his car burst into flames, demonstrating the inadequacies of the safety systems of the times. My mother was emotionally devastated and resolved to ease out of her involvement with BRM.

Stepfather was not heartless but he dealt with the deaths on the track in a very different way. He must have been affected. Talking about a death made him stern, but I never saw any sign of emotion. He was an enigma.

My mother’s role in Formula One was an odd one. Stranger still in the 1960s, she was in the macho world of motor racing. She chose to be the ambassador for her family company. In the early years, when we were all young, she was a passionate supporter of her team. She advised but she had no official role. However, as my uncle got busier and more races were held on Sundays, she and my stepfather took more control. When it was clear that Uncle Alfred would not be able to retake the reins of the company after he suffered a debilitating stroke in 1969 my cousins agreed that, as my mother knew so much about the Grand Prix circuit, she should take on the running of the team. But what were they to do with Louis Stanley? He had been causing trouble for the company for many years, so much so that my uncles employed a gatekeeper to confine his bizarre ideas for development to paper. Not only that, but he had taunted my uncle by writing libellous articles about him. However, the family took his antics on the chin. A compromise was made and it was here that my cousins made my mother and him joint managing directors of BRM. At least that way they could keep their ‘uncle’ off their backs while they dealt with the parent company.

I return to the day I first drove to Cambridge after hearing my mother had suffered a stroke. Stepfather’s short message reported she had suffered only a mild stroke, but my legs felt weak as my body responded to my brain’s commands to get out of the car. What was I going to find? It was a nasty feeling that would return, time after time, over the next two years.

The bell still jangled merrily over the blue gate but as soon as I entered the courtyard things felt different. It was gloomy. There were no powerful kitchen lamps lighting the way to the back door. There was no Mum at the butler’s sink looking out through the netted kitchen window for me. Nobody came to the back door, so I had to ring the bell. The back door was actually the front door now but it had kept its wrong nomenclature since the increased traffic made it uncomfortable to sit under the veranda and the front gate was boarded up for lack of use. This left the blue gate the only entrance to the yard and, beyond that, the house.

Inside, there was no noise and the air was cold. The four forceful gas hobs that were always burning in the kitchen were turned off. The radio was silent and there were no remnant smells of cooking.

Mum was lying on her double bed, awkwardly placed on her back. How had she got there? Why was she not in hospital? She was unable to move but her glazed eyes gave me slight hope, as there was some semblance of recognition. Suddenly I realised I knew nothing about the care of stroke victims but it seemed odd that she was lying on her own bed with no medical attendance.

Stepfather kept repeating, ‘Everything will be back to normal in a few days’ time.’

His face held a grim expression and was serious but he was friendly enough.

‘What can I do to help?’ I asked.

‘Thank you, but no thank you,’ he replied. I had heard him say that many times before.

My siblings had all turned up and there was general murmuring as to the when and why of my mother’s health. It appeared she had been getting ready for bed the night before when she suffered her stroke. The faithful weekly cleaner had said she had been unusually stressed. We whispered together as to why Louis had waited until eight the following morning to call the GP. It was all very peculiar. But I told Stepfather that I would stay the night and went to bed in the narrow bedroom next to theirs. As I tossed and turned, I could hear mumbled voices through the wall. I willed myself to believe that my mother’s speech was a sign of her early recovery. But it was not long before the quiet footsteps of Louis came to rest outside my door. I wanted to pull the covers over my head. The door handle turned. I heard him ask if I could help.

The sound of his approach had reminded me of the terrifying nights of my childhood…

When Mum came into my bedroom to say goodnight I demanded to be tucked in tightly. She saw it as a game. Sometimes, when she was reading me a bedtime story, the whole room seemed to joggle up and down when Stepfather came to give me a goodnight kiss, his footfalls evident from the protesting floorboards outside my room. More undesirable were his ‘other’ visits. Mum would have gone downstairs to prepare his supper, as he eased the door softly open. The hinges creaked, but only quietly, and his footsteps made the ornaments quiver, not shake.

He found an excuse to talk and, after cocking an ear, he would reach down under my blankets. I didn’t like it. I did not know why I couldn’t confide in Mum. I just knew I couldn’t.

The abuse progressed. He started showing me his penis and how it grew to be a different shape. He never wore underpants. He demanded I touch it and I was pleased when he allowed me to escape this task by turning the other way. It all seemed very eerie and unnerving. He would grunt a little and then get his handkerchief out of his jacket pocket to clean himself up. I was desperate to keep my eyes closed because all the action seemed very close to my face.

I tried to shut down my brain, but then the nightmares began. I was possessed by a recurring dream. I had a passion for Matchbox toys. Every Saturday I looked forward to buying a new vehicle with my two-shillings-and-sixpence pocket money (12.5p in decimal money), but in the nightmare instead of dreaming of the Matchbox containing a miniature steamroller, I woke with a deep apprehension that it might have a tiny living baby inside.

The visits kept getting worse. Even though I was innocent of even the most basic facts, he started to talk about watching Mum and him doing something in their bedroom. The depth of my nightmares increased and with a heightened sense of survival I knew I had to stop him.

Then one night he said he would arrange for me to be hidden in one of the cupboards in their bedroom. This sounded petrifying and I was rigid with fear. I kept thinking and scheming: there must be a way of stopping him. My final plan was simple: I would shout as loud as I could. It was something I could do. Once I had my plan I was full of resolve and keen to put it into action. But, the next time he walked furtively across the bouncing floor, the resolve ebbed out of me. I was furious with myself for my inability to stick to my scheme.

I don’t know how many times I let myself down. Each failure created more self-doubt and frustration. When I opened my mouth all I could hear was my breathing. I decided practice was needed, so I went down to the bottom of the garden and let rip.

The next time he entered my room I screamed and screamed and screamed. He turned to leave, only to meet Mum rushing towards my room with her apron awry and her hands covered in flour. She looked aghast.

‘What on earth has happened? Are you alright? Have you had a bad dream? What’s happened to you?’

Her words came tumbling out. I sat bolt upright up in bed, looking out of the window, with the orange street light falling across my covers. I had tears in my eyes but I wasn’t crying. I had done it. Mum never asked me again why I had made so much noise. But, from that night on, the abuse stopped.