Читать книгу The Social and Political Thought of Archie Mafeje - Bongani Nyoka - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2 | A Totalising Critique

When I went to Langa to do fieldwork in 1961, I was armed with an essentially ahistoricist and overly functionalist question: Why and how do social groups cohere or split? Historically, it is necessary not to accuse me of inanity but simply to acknowledge the fact that I should have known that ebbs and flows are the very movements of which the dialectic of history is made, and, as such, are permanent features of collective existence.

Archie Mafeje, ‘Religion, Class and Ideology in South Africa’

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, Archie Mafeje had managed to reconcile his Marxist political convictions with his academic work.1 He had moved on from his liberal functionalist work of the 1960s to write from a Marxist perspective and also to advance a programmatic critique of the social sciences.2 Yet those who are enthusiastic about polemic tend to reduce his evaluation of the social sciences to a polemic on anthropology. Theirs is the standard or conventional view, which holds that he single-handedly demolished anthropology as a discipline, or that he single-handedly destroyed the science of anthropology. This conception of Mafeje’s work is misleading in at least three respects. First, while it is true that the discipline of anthropology underwent a crisis for at least two decades, its system of thought shaken, it is not true that it was demolished – for all its problems, anthropology is still a thriving academic discipline. Mafeje, Bernard Magubane and Francis Nyamnjoh would not, as late as the twenty-first century, have felt the need to analyse a discipline dead and buried. Second, the idea that Mafeje ‘single-handedly’ demolished anthropology is factually and historically incorrect – there were a number of other radical social scientists who dissected anthropology from the late 1960s to the 1980s. Third, the suggestion that Mafeje only criticised anthropology made him seem a reformist scholar. However, a careful reading of his analysis of the social sciences more broadly suggests that he was in fact a revolutionary scholar. Mafeje understood what other radical social scientists did not: that all the social sciences are Eurocentric and imperialist and the focus on anthropology to the exclusion of other disciplines is founded on reformism. He called for the adoption of a thoroughgoing commentary of the social sciences, which would lead to the emergence of what he called ‘non-disciplinarity’.3

Thus the excessive focus on Mafeje’s assessment of anthropology is a one-sided and partial reading of his oeuvre. Mafeje traced the development of anthropology and its impact on Africa in relation to the other social sciences. Having traced anthropology’s role in colonialism and imperialism, he acknowledged that it was bound to be plunged into deep crisis precisely because of anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist struggles. Mafeje thus advocated the importance of the study of ethnography in the social sciences in Africa.

Sociology of knowledge and the ‘totalising critique’

Mafeje’s 1975 essay ‘Religion, Class and Ideology in South Africa’ is not only a brilliant analysis of social change, but also a pioneering work in the sociology of knowledge. Together with ‘The Ideology of “Tribalism”’, it marks a significant departure from standard anthropological and sociological writings on Africa. The 1975 essay, moreover, constitutes an auto-critique of his earlier work with Monica Wilson on Langa. Evaluating some of the themes pursued in Langa, Mafeje focuses in particular on those aspects that dealt with religion; outlining his theoretical matrix, he singles out a controversial question in the epistemology of the sociology of religion. The question turns on whether it is possible to reconcile a belief in an ‘extra-societal source’ – the transcendental viewpoint – and a belief in a positivist conception of science.4 In other words, the conflict seems to be about whether belief systems are a reflection of concrete realities – experience – or an outcome of higher or divine intervention. This challenge compelled secular theorists to make a distinction between sociologists of religion and religious sociologists. For Mafeje, this reinforced the positivistic notion of value-free or non-partisan science. Just as materialists are confronted with the problem of consciousness and empirical history, positivistic idealists are similarly confronted with the problem of theodicy. As a result of the functionalist approach, South African sociology of religion was confined to narrow studies of churches and tribal rites and their function in society. Yet, ‘the preoccupation with institutions has meant a narrowing of context to a point where some of the more general ramifications of belief systems and some nascent forms of commitment are made to appear as something apart’.5 This is Mafeje insisting on taking into account history and the wider sociopolitical context – his argument is that functionalist analyses of social phenomena or ‘functionalist organicism’ interpret social change as if it only meant ‘a substitution of one set of institutions with another’ because of the tendency to study social institutions as if they were disconnected, rather than to focus on societies as a whole.6 At the descriptive level, this may well be valid, but at the substantive level it serves as what Mafeje terms an ‘ideological mystification’ of underlying societal issues. Accordingly, social change, such as is understood by functionalist and positivist sociologists, does not necessarily connote the radical historical transformation advocated by Marxists. In analysing social change, Mafeje appeals primarily to the sociology of knowledge and attempts to relate sociological phenomena to its material substratum, class and ideology.

Writing in response to Magubane’s well-known essay on the review of social change, ‘A Critical Look at Indices Used in the Study of Social Change in Colonial Africa’, Philip Mayer says: ‘The considerable interest of Magubane’s paper seems to me to lie in its contribution to the sociology of knowledge rather than to the theory of change. The author’s own “existential” situation is therefore of some relevance, especially as such single-minded onslaught of “colonial anthropology” seems almost anachronistic in 1970. He is speaking out of personal experiences which have clearly affected his perspective.’7 There is a lot riding on this quote. First, Mayer is not praising Magubane, or if that was his intention, the compliment is surely backhanded. Second, Mayer sets up a false dichotomy between the sociology of knowledge and contribution to the study of social change. In the process, he disdainfully discards the relevance of one’s existential experiences in the process of knowledge making and, in so doing, confirms both Mafeje’s and Magubane’s commentary on, respectively, the positivistic nature of social anthropology and sociology in Africa. Mayer wrote as though social scientists write neutrally and objectively, without being influenced by the sociological baggage of their socio-historical backgrounds. His argument accords with the issues raised by Lewis R. Gordon when he says that such treatment as black intellectuals get from their white counterparts, where it is not patronising, is so contemptuous that they are seen as providers of experience, rather than as knowledge makers in their own right.8 Yet taking seriously one’s lived experiences is precisely what enabled both Mafeje and Magubane to see through the colonialist and imperialist nature of the social sciences in Africa. Third, Mayer is unable to see through the colonial nature of anthropology, even as late as the 1970s – which is precisely because of his failure to acknowledge the importance of one’s own socio-historical and biographical experiences. By contrast, however, and in taking seriously the sociology of knowledge, Mafeje was able to understand the totality of South African history without getting entangled in the idealistic arguments that characterise the works of liberal functionalist and positivist sociologists and anthropologists in South Africa. This is what he calls a totalising critique.

The holistic historical approach is important for Mafeje because, as he says, ‘a sociology of knowledge that operates outside of particular historical contexts seems futile’.9 In acknowledging the importance of history and context, Mafeje parts ways with liberal idealists who only focused on what he terms minor contradictions and perversions of South African society. For Magubane, colonial anthropologists – in refusing to acknowledge that colonialism is an essential dimension of the present social structure – assumed that its general characteristics are already known and therefore one could conduct research without situating these characteristics in their historical context. What is essential in understanding social change, Magubane argues, is ‘a total historical analysis’.10 In accounting for changes in African urban and rural settings, colonial anthropologists spoke of ‘Europeanisation’, ‘Westernisation’ or ‘acculturation’. In so doing, Magubane says, they thought Africans were aspiring to a Western way of life and did not take into account that Africans were deprived of their being and knowledge systems. Colonial anthropologists, according to Magubane, played down the fact that the purported acculturation of Africans hinged on three stages. First, there was a period of contact between the coloniser and the colonised, in which the latter were defeated through physical force. Second, there was a period of acquiescence during which some Africans were not only alienated from their societies, but also acquired the ‘techniques and social forms of the dominant group’, such as religion and education. Third, there was a period of resistance in which Africans ‘developed a “national” consciousness that transcends “tribal” divisions and confront the colonial power with the demands of national liberation’.11

There is an overlap in these stages. But they must all be taken into account if one is to survey social change in Africa in a meaningful way. Thus, for Magubane, colonialism had at all times to be the natural starting point. Social anthropologists and sociologists tended to ignore the fact that the different stages of change in Africa were accompanied by force and coercion, and to focus on appearances and superficial issues that do not scratch beneath the surface, so that many of the conclusions reached were no more than impositions of dominant values on Africans. These studies also tended to take on micro units of analysis, such as individual behaviour, rather than society at large, whereas the study of social change requires that one examine not only the victims of oppression, but also the structure of domination itself and the methods used by the oppressor to maintain the oppressive structure.

Anthropologists have a tendency to create a dichotomy between rural and urban communities. For Mafeje, there is a dialectical link between the two settings. Based on the fieldwork he conducted in Langa township and the rural Transkei for his Master’s thesis, he argues that, sociologically, town and country are not polar opposites – the ‘Christian atmosphere’ that permeates Langa township is also to be found in the rural hinterland of All Saints, an Anglican mission station in the Engcobo District. The same can be said of cultural practices – the migrant worker who lives in Langa is the same man who goes home to perform cultural rituals during holidays or for subsistence farming in his retirement and, furthermore, the so-called pagans of the Transkei are to be found in the migrant worker barracks in Langa. Mafeje writes: ‘In South Africa after 1½–2 years I was able to interview in the Transkei, a rural area, the same men as I had interviewed in Cape Town. In Uganda before I had finished my 15-month survey some of the poorer farmers had disappeared to the city for employment or were commuting by bicycle.’12

According to Mafeje, what becomes ‘a curious logic of colonial history’ is the fact that the pagans, or amaqaba, who were once considered conservative insofar as they refused to give up their African ways of living, became latter-day militants through the sheer force of their resistance to Christianity and the Western way of life. They found allies in the urban-based militant youth who rejected Christianity and racism by appealing to an African God. Mafeje finds that the youth in Langa were not only indifferent to the church, but were also dissatisfied with it – and that was partly why they condemned Christianity as a ploy by whites to oppress and exploit black people. The grievances and feelings of the youth ‘are genuine and they explode with anger and frustration’.13 Mafeje says there may have been a difference between the two – the militant youth (who rejected Christianity and spoke of an African God) and amaqaba, the rural dwellers (who rejected Christianity and the Western way of life) – at the level of theoretical self-consciousness, but there were also affinities. The rural-urban thesis, much loved by anthropologists and sociologists of social change, was no more than a false dichotomy, for the same white supremacist ideology was found in both settings – in the church, white liberal ideology reproduced itself through missionary work and education. Mafeje is, however, too quick to find positive features in this colonial arrangement when he says: ‘While at first this represented a progressive force, by introducing the arts of writing and universalising metaphysical concepts in small pre-literate societies which relied on simple theoretical paradigms for explanation, later it became reactionary, precisely by failing to come to terms with the contradiction of its own emergence in peculiarly South African conditions.’14

Mafeje unwittingly accepts the ‘civilising mission’ of the missionaries, but fails to locate its logic in its wider sociological and historical context. The sheer enormity of pain and oppression accompanying this ‘civilisation’ simply overshadows the supposed ‘progressive force’ about which Mafeje speaks. The colonial project, suitably interpreted, was about plundering, looting and subjugating. Civilisation, if it must be so called, is a by-product and not the driving force of colonialism. Mafeje is here pandering to the social change theory of colonial social scientists. Once again, Magubane’s work is instructive in this regard. Magubane argues that because social scientists of the time were reluctant to criticise colonial governments, they chose to play it safe and did not expose the truth about colonial rule or touch on matters political, but simply focused on anodyne issues such as blacks speaking English, wearing European-style clothes or buying expensive cars. To the extent that they touched on colonialism, they depicted it as a necessary stage in history and considered how its long-term effects benefited African people. They ignored altogether the suffering, exploitation and degradation of Africans and their value systems. Thus, when the theory of social change accounts for social change in Africa, it does so in mechanistic and ethnocentric terms. When social scientists saw change, they saw tribesmen who were becoming Europeanised, mistaking appearance for reality. In this respect, they saw the fulfilment of white supremacist ideals – hence the notion that the African was being ‘civilised’.

Notwithstanding Mafeje’s claim about the progressive nature of liberal ideology, he nevertheless acknowledges that being civilised did not necessarily mean automatic acceptance of the white liberal middle-class cosmic view. Liberal theory, which has always taken for granted its own supposed progressiveness, was put under the spotlight and its hypocrisy exposed by Mafeje. It was unable to transcend itself insofar as it treated black people as perpetual subordinates in need of tutelage. The liberals sought to produce ‘black “carbon-copies” of white Christian orthodoxy in South Africa’.15 Mafeje posits that, from the point of view of the sociology of knowledge, the liberal might not be able to transcend their own ideological limitations. Following Max Weber, Mafeje reminds sociologists of knowledge that ideologies cannot be transcended because they can be both objective and subjective at the same time. The best that people can do is to endure ideologies ‘stoically’. Insofar as Weber accepted the view that ideologies cannot be transcended, Mafeje admits that Weber ‘paid the price of being radical without being revolutionary’. In invoking the sociology of knowledge, Mafeje’s attempt was to build a case against the supposed value-free or non-partisan positivist belief generally, and functionalism particularly.

On positivism and functionalism in anthropology

The issues above were not unique to the social sciences in South Africa, but were characteristic of the social sciences more generally. Indeed, anthropologists and sociologists in other parts of the world had, by the 1960s, begun to question the status of anthropology as a discipline as well as the categories anthropologists used in understanding Africa and other ‘less-developed’ societies. In the essay ‘The Problem of Anthropology in Historical Perspective’, Mafeje surveys the diverse manner in which critics of anthropology in the North aired their views on the status of anthropology and found that in the American academy criticisms of anthropology were largely ideological, rather than theoretical. In Britain, on the other hand, he found the discussion less ideological, so as to give it respectability in the name of an academic dialogue.

These discussions and revisions led to what Mafeje calls ‘neopositivist conceptions’ of the French anthropologists.16 Neopositivism was to be found in Lévi-Straussian structuralism or in liberal relativism, which was couched in neo-Marxist jargon. According to Mafeje, this was an ideological tactic all of its own. Unlike in the United States and the United Kingdom, in France there was a sharp divide between Marxist and non-Marxist anthropology. Although the scholars attempted to place on the table issues that plagued anthropology as a discipline, Mafeje nevertheless felt that the problematic they grappled with was badly formulated from the start. Characteristically, the critics of anthropology in the United Kingdom lacked a totalising critique and sought to rehabilitate anthropology by suggesting that it was not always in the service of colonialism and imperialism. The ‘militantly critical anthropologists’, on the other hand, allowed their analyses to remain at the level of ideology and polemic, the upshot of which was self-contradictory appellations such as ‘radical anthropology’ or ‘socialist anthropology’. Yet, as Mafeje eloquently argues in his essay on the problems of anthropology, ‘it is as hard to fit socialist clothes on an imperialist offspring as it is to transform positivism by radicalising it’.

In short, the two sides of the divide are best understood as reflective of the complicity of opposites. They take different routes only to arrive at the same conclusion: there is a better side of anthropology, which can be rescued. Magubane, a critic of anthropology himself, was not spared Mafeje’s criticism. Mafeje reminded Magubane of the importance of the sociology of knowledge in shaping one’s ideas. Not only was Mafeje censuring Magubane, he was also conducting auto-critique, arguing that in singling out colonial anthropology as the problem, its critics were undialectical and thus created an epistemological impasse. They identified, in anthropology, functionalism and imperialism, but failed to link these to the ‘metropolitan bourgeois social sciences which are equally functionalist and imperialist’.17 They failed to advance the totalising critique about which Mafeje spoke. As far as he was concerned, the problem of anthropology was primarily theoretical (‘universal’) rather than ideological (‘colonial’), for merely to point out that anthropology was a handmaiden of colonialism was to present the argument in a partial and ideological way – that it was colonial could not have been its single diagnostic attribute. Epistemologically, its biggest crime was positivism, functionalism and alterity.

The Enlightenment, out of which anthropology and the other social sciences were born, was inherently bourgeois and sought to universalise anthropological viewpoints. This then laid the foundation for the European civilising mission of the nineteenth century – ‘the highest point of European colonialism’.18 The European civilising mission was not a noble endeavour. In the main, its rationale was ‘economic plunder, political imposition and other inhumane practices’. While these practices took extreme forms in the colonies, they had in fact started in Europe and were an expansion of European capitalism. Magubane argues that the first colony of England was Ireland, where the English first tested colonialism and put it into effect. For Fanon: ‘The well-being and the progress of Europe have been built up with the sweat and the dead bodies of Negroes, Arabs, Indians and the yellow races.’19

The European expansionism about which Mafeje speaks served as a source of inspiration for European scholars of the Enlightenment. This, then, is the substratum that served as a basis for the philosophies and ideologies of European expansionism from which metropolitan bourgeois social sciences cannot be separated and it is important at all times to connect it with anthropological writing in Africa. Having laid this foundation, Mafeje reasons that functionalism, which is a particular paradigm within the social sciences, is the natural starting point. Although functionalism had been discussed, few anthropologists had analysed its ideological status in the age of European expansionism. Those who attempted to do so fell into the trap of associating functionalism only with the discipline of anthropology and with the historical epoch of colonialism. Yet, as Mafeje says: ‘In the same way that capitalism, as a specific mode of accumulation, had to exist before imperialism could manifest itself, likewise functionalism, as a theoretical rationalisation of the epoch, had to exist in the metropolitan countries before it could be used in the colonies.’20 Moreover, ‘in its paradigmatic form functionalism is a product of nineteenth century Western European bourgeois society, and was never limited to a single discipline called “anthropology”. On the contrary, it straddled all the life sciences.’ In the nineteenth century, functionalism relied mainly on analogies derived from physical and biological sciences to account for complex social phenomena. The other version of functionalism, rationalist-utilitarian, ‘was a reflection of the logic of the industrial revolution in England and France’ and the two pioneers of modern functionalism, August Comte and Herbert Spencer, came from France and England respectively. For them, rationality, utility and functional value, order and progress were foundational to a bourgeois European society. These principles affirmed its achievements and justified its continued existence. Such theories in the works of Spencer and Comte served as an inspiration for Émile Durkheim, who synthesised them and came up with structural-functionalism. If it were not for the synthesis of Spencer and Comte in Durkheim’s work, structural-functionalism ‘would not have emerged in anthropology in quite the same way that it did’.21

The Spencer-Durkheim theoretical nexus laid the foundation for the works of British anthropologists such as Bronisław Malinowski and Alfred Radcliffe-Brown, who both owed their greatest intellectual debt to Durkheim primarily and to Spencer and Comte secondarily. For Malinowski, the premium was on the psychological and biological needs of the individual, so that social and cultural institutions were merely a response to the said needs – a Spencerian understanding of society. Radcliffe-Brown, on the other hand, following Durkheim, stressed the autonomy of social institutions and sought to understand how disparate social elements and institutions were instrumental in maintaining the social whole. But Radcliffe-Brown remained faithful to Spencer’s use of biological analogies, as did Malinowski. Malinowski’s and Radcliffe-Brown’s writings greatly influenced American functionalist sociologists such as Talcott Parsons, George Homans and Robert K. Merton.

The foregoing description does not, in my opinion, complete the picture. For one thing, sociologists have also been influenced by Max Weber, Durkheim’s contemporary, whose work reminds them that not all positivist sociology is functionalist. Weber rejected the use of biological or natural science analogies in explaining social phenomena. He appealed to individual subjective meanings by using ‘ideal types’ and ‘normal types’ as suitable methods of sociological analysis. Mafeje says: ‘For him, unlike Talcott Parsons, adaptive behaviour on the part of individuals was no measure of the “functionality” of the system. Rather, systems functioned because they had an internal logic, whether it was good or bad individuals – a question which Weber treated as a purely subjective matter.’22 Mafeje believed that ideas and social forms are shaped by particular nations and bourgeois classes at any particular time. Positivism and functionalism are examples of such ideas. It is not clear, therefore, whether bourgeois writers such as Spencer could espouse neutrality and ‘positive science’ and still be faithful to their class interests. For Mafeje, this was an attempt on their part to gloss over social contradictions that were manifest in Europe, where there was inequality, exploitation and unmitigated sociological individualism – the upshot of capitalism.

Having discussed the link between the Enlightenment and functionalism, I now turn to how the latter found expression in the colonies through anthropology. It should be remembered that, for Mafeje, anthropology was in the colonies what other social sciences were in the metropolitan countries – and to single out anthropology and leave out the other social sciences is a form of mystification. Moreover, functionalism was the prevailing paradigm in both the metropole and the colonies. That anthropologists lent their support to colonial governments was not Mafeje’s main contention; the issue, for him, was the ontology upon which the intellectual efforts of anthropologists are premised. Equally, it is beside the point whether any anthropologists were opposed to colonialism. In the final analysis, the contours of anthropology are as much colonially determined as they are informed by functionalism; the oppositional anthropologist and the colonial anthropologist are in unison with regard to the utility of social research institutes in Africa. Mafeje saw that it was significant that their units of analysis were the same: tribe, kinships and religious systems. On both sides of the purported divide, therefore, the anthropological enterprise was bourgeois ab initio.

For Mafeje, assessing the works of the older generation or the colonial anthropologists was not simply a reflection of a generation gap. It was a negation of negations. Just as functionalism is a negation of speculative history in the Enlightenment, it is also an affirmation of bourgeois capitalist utilitarianism that oppresses the people of the global South and reproduces itself by producing native objects of study, who would later be identical to the ‘knowing’ subjects through the process of bourgeois conversion. In this regard, Mafeje said that he, along with Magubane, were products of colonial anthropology. The crimes of colonial anthropology were not merely based on descriptive and superficial writings about modernising Africans who sought European status. The crimes lay in its ahistoricity, which failed to retrace the problems confronting African people to colonialism. Mafeje believed that he and Magubane had to be part of bourgeois functionalism in order to be its negation. Analogously, African revolutionaries had to be part of colonialism in order to experience its frustrations. To ignore these factors, said Mafeje, was to fall victim to undialectical presumptuousness. Although anthropologists were among the first social scientists to arrive in the colonies, they should not be singled out as the only functionalists and academic imperialists. Functionalism and positivism were not unique to anthropology, but characterised all the social sciences. Mafeje’s point is well taken. Yet it raises more questions than it answers. If the crime of social science lies in its being functionalist and positivistic, what would Mafeje have had to say about the social sciences that are not functionalist or positivistic in their epistemology? What would be said of the social sciences grounded in Marxist dialectical materialism – as Mafeje’s analysis clearly is? In a sense, it appears that what Mafeje criticised was bourgeois social science, rather than social sciences as such.

Against this background, Mafeje was able to criticise anthropology without turning it into the ‘black sheep’ of the social sciences. Anthropology was the first to arrive in the colonies because the bourgeois metropole needed it in order to conquer the natives, about whom they were least informed. That it coincided with colonialism is hardly surprising since anthropology provided knowledge and access to hitherto unknown societies. Thus, to fixate on anthropology to the exemption of other social sciences – which were equally bourgeois and imperialist – is to engage in petty reformism, which does not take seriously history and the totalising critique.

Mafeje therefore advocates a holistic approach that transcends disciplines. Such an alternative is to be found, he suggests, in Marxism. He argues that there could be no disciplines within Marxism, and then he goes on to query the function of disciplines in society. He says that disciplines are there to illuminate problems of fragmented social existence and, in doing this, social scientists assume that it is for the benefit of ‘uncomprehending ordinary people’. The assumption made by social scientists then leads to the bourgeois epistemology of subject-object relation. Mafeje clinches his argument by saying: ‘If the function of bourgeois social science is to increase the awareness (or false consciousness) of uncomprehending objects, then when the people have become comprehending subjects, there will be no need for social science.’23

Mafeje’s argument is not entirely convincing. This is an issue distinct from the critique of (bourgeois) social science. The non-disciplinarity that would emerge from transcending disciplines would still constitute social science. Marx was concerned with the ordering of society and social relations (the subject matter of social science) rather than biological or natural sciences. The paradox of the charge of Eurocentrism against functionalist-positivistic social science is that Marxism is itself fundamentally Eurocentric. The problematic that it sets itself is mainly Europe; speaking specifically to the European conditions – even if it could be appropriated (with considerable modifications) for the revolutionary projects in the (former) colonies.

In order to understand where Mafeje was coming from, one has to read him outside of the text. In other words, context is crucially important. In his search for alternatives, Mafeje was also limited by his background and environment. The issue is not whether Mafeje succeeded or failed in the very difficult task he set for himself. The point is to follow his line of thought and to see what insights African social scientists may garner from him in the quest for knowledge decolonisation. For a Unity Movement-trained Marxist such as he was, their internationalist outlook would have prevented him from adopting what he called an Africanist or even nationalist perspective on these issues. As far as he and the Unity Movement were concerned, to be Africanist or nationalist is to be reactionary.24 He said at one point, for example: ‘In the name of international socialism Pallo Jordan and I were trained to think that “nationalism” was narrow-minded, bourgeois, and, therefore, reactionary.’25 If the sociology of knowledge is to be taken seriously, then this biographical detail and the context in which Mafeje wrote ought to be fully appreciated and not seen as a rationalisation of his argument.

Mafeje championed Marxism insofar as it does not recognise disciplines. Thus, according to him, even claims to Marxist anthropology or Marxist sociology are self-contradictory. Equally, Marxism cannot be interdisciplinary without being self-contradictory. The difficult question, then, is what the role of disciplines is in the social sciences. The answer is usually that the social sciences make complex sociopolitical issues apparent to uncomprehending laypeople. This is Mafeje’s representation of it. The social sciences could well be for comprehending subjects. Most scholarly works are addressed to other scholars, in much the same way that the Grundrisse and Das Kapital are addressed to intellectuals, not the peasant or the factory worker (the complexity of scholarly writing had to be diluted in pamphlets to make it more comprehensible to the literate among the masses). According to Mafeje, the crux of the problem of the social sciences lies in their bourgeois epistemology of subject-object. Although it is said that the role of the social sciences is to increase the awareness of the unknowing objects, it is unlikely that this is so, for even when people become comprehending subjects, the social sciences still exist. In the final analysis, Mafeje argues, the role of the social sciences is politics and therefore ideological: ‘Participation in the making and execution of decisions by either “knowing subjects” (experts, advisors and consultants) or liberated objects is a political process. Then Marxist theory which advocates revolutionary politics and which denies separation between subjects and objects, between theory and practice, between value and fact, and between science and history comes [into] its own. At the most fundamental level, it is the best anthropology that there is and the best candidate for future society.’26

Thus, ‘if dialectical materialism is a theory of history, then historical materialism is its methodology’.27 Marxists are acutely aware of the distinction between theory and practice – hence the idea of praxis. The fact that practice informs theory or vice versa is no reason to suppose that Marxism denies separation between the two. Although Mafeje declares that Marxism ‘is the best anthropology that there is’, he is willing to subject it to critical scrutiny when its categories do not adequately address the concrete cases they are meant to address.

On idiographic and nomothetic inquiry

In his essay ‘On the Articulation of Modes of Production’, Mafeje is concerned with understanding at least five important issues. The first is a question: Does idiographic inquiry yield deeper insights into societal processes than nomothetic inquiry?28 He raises this issue specifically because he wants to understand whether traditional disciplines such as history and anthropology (both of which are idiographic) are the best candidates accounting for societal processes vis-à-vis Marxism, which makes nomothetic claims such as ‘the theory of modes of production’. Mafeje’s second issue is the mode of production as a unit of analysis, a worthy substitute for such concepts as tribe or nation, both of which are used by historians and anthropologists.29 The third issue is that since Marxism tends to treat culture as purely a superstructural phenomenon (which has little influence on the base that produces the necessities of life), what is the relationship between cultural relativity and meta-theory? The fourth important issue asks what (if world history and anthropological philosophies are necessarily Eurocentric and therefore inadequate and unacceptable) counter theories one can generate from the global South. Finally, Mafeje’s fifth issue, also a question, asks what – in an otherwise imperialist world – is the responsibility of the social scientist? These questions speak not only to the problem of theory, but also to the sociology of knowledge. Mafeje proposes to approach the general through the particular, and herein lies the genius of his approach. In grappling with these questions, Mafeje discusses the works of two Marxists, Harold Wolpe and Michael Morris, who wrote about South African capitalist relations and specific mechanisms of labour reproduction in the twentieth century.30 In their attempts to understand South African conditions, they deployed Marxian categories such as class, mode of production, production relations, forces of production and social formation.

Mafeje wants first to clarify what it is that the two writers meant by these concepts, and then to understand how such concepts explain the concrete conditions they are meant to explain. Although he wants to clarify, he is equally concerned to comprehend the applicability of the concepts and their usefulness in different conditions. This is so because while the concepts seem theoretically reasonably precise, substantively they need further clarification. Wolpe, following Ernesto Laclau, made a distinction between a mode of production and an economic system, of which he sought to understand the constituent elements – capitalist modes of production, the African redistributive economies and the system of labour tenancy. For Mafeje, the latter two concepts were a deviation from Marxism and empirically unreliable.

For Morris, on the other hand, a mode of production was an articulated combination/structured combination or, more precisely, a determinate structure. On this score, a mode of production is combined precisely because modes of production do not follow one another sequentially, with one replacing the other; nor is a mode of production produced by movement or changes within it. To argue as Morris did is to ignore the Marxian dictum that the struggle is the motor of history. For Mafeje, this led to a theoretical confusion because there can be no theory of articulation between modes of production. According to Morris, contradictions occur in class struggles within a given social formation, not between modes of production or within a mode of production – but an argument of that sort abandons dialectical materialism altogether. Morris’s thesis, Mafeje argues, could only be valid if class struggle (which is concrete) is used to mean the same theoretical or abstract construct (mode of production) used to explain it. In other words, a mode of production is a theoretical concept to explain the sociopolitically concrete. In Morris’s account, however, the two are used somewhat interchangeably. According to Mafeje, Morris’s thesis cannot be valid ‘unless the material conditions of class struggle are accorded the same theoretical/logical status as the mode of production to which they refer. In orthodox Marxism this is provided for in the concept of “contradiction” within a mode or between modes of production.’31

Both Morris and Wolpe agreed that ‘all modes of production exist only in the concrete economic, political and ideological conditions of social formations’.32 But it is doubtful that Wolpe agreed with Morris’s rejection of the articulation of modes of production; although Morris used the term ‘social formation’, he did not define it theoretically. Mafeje notes that in Wolpe’s schema, on the other hand, the concept refers to specific ‘mechanisms of social reproduction or the “laws” of motion of the economy’. By ‘mechanisms of social reproduction’, Wolpe meant a combination of modes of production. For Wolpe, ‘the distinction between the abstract concept of mode of production and the concept of the real-concrete social formation conceived as a combination of modes of production constitutes the explicit or implicit presupposition of all these articles’.33 Wolpe was referring here to chapters in the collection of essays he edited. To the extent that the distinction between the two concepts is either implicit or explicit in all the essays in the collection, Mafeje reasons that the authors had clearly ignored the view that the term ‘social formation’, even for Marx, can be both an empirical concept that refers to the object of concrete analysis and, as Étienne Balibar puts it, ‘an abstract concept replacing the ideological notion of “society” and designating the object of the science of history insofar as it is a totality of instances articulated on the basis of a determinate mode of production’.34 To this Mafeje adds that one ought to make a distinction between abstract concepts and the concrete referent that needs to be explained.

Having discussed these abstract concepts, Mafeje is keen to analyse the empirical issues they were meant to explain. Broadly speaking, Wolpe’s thesis was that, with regard to the dialectic between urban and rural, the pre-capitalist mode of production ensured (or otherwise maintained) the reproduction of migrant labour. For Morris, it was the labour migration from white farms that maintained the reproduction of the labour-power of migrants. Although farmworkers were allocated pieces of land by the white farmer through the so-called labour-tenancy, they still sought work either on other farms or in the cities. This argument, such as was presented by Morris, that farmworkers could hold more than one job, ‘is tantamount to [saying farmworkers supplement] wage with wage’,35 without giving a clear indication as to the supposed essential difference between the labour tenant on a white farm and his peasant counterpart in the rural areas who uses his labour power for his own subsistence.

This prompts the question as to the real difference between Wolpe’s and Morris’s theses of labour reproduction. For Morris, the difference between feudalist and capitalist relations of production lay in the difference between land rent and wage labour. Morris used the organising concept of ‘relations of real appropriation’ to understand this dynamic, but even so he oversimplified the social relations on white farms. The pre-capitalist South African case need not translate into feudalism by virtue merely of ground rent and landlordism. South African society was polyglot, unlike that of Russia. For Wolpe, the capitalist mode of production was linked to other modes of production, ‘the African redistributive economies and the system of labour-tenancy and crop-sharing on White farms’.36 Mafeje argues that this definition of a mode of production lacks rigour because ‘labour-tenancy’ and ‘crop-sharing’ connote two different things. Nor do they lend themselves to categories of ‘feudalism’ and ‘capitalism’. Thus, when the colonial government ensured that Africans could never rise to the level of capitalist or commercial producers, they fought for their existing pieces of land and grazing rights for their livestock, and they sent family members to the rural areas with the stock they would have accumulated on white farms.

Those who engage in this practice, particularly in the Eastern Cape, are referred to as amarhanuga, those who go around collecting value (in the form of livestock) specifically from white farms, whereas those farm wage labourers uprooted from white farms are called amaqheya. Mafeje asks whether livestock could be thought of as property (means of production) or merely instruments of production. In the South Africa of the time, what did it mean to speak of property with reference to black people? For both Morris and Wolpe, property referred to land in the agricultural economy. Wolpe incorrectly said that land in the rural areas was held communally. Mafeje argues that this is inaccurate because arable land was individually registered at the magistrate’s court, the head of the family accepting liability for annual rent. Strictly speaking, therefore, such land is owned by the state and not the individual. In this sense, peasant cultivators of the land are tenants of the state. The difference between peasants and tenants on white farms (amarhanuga) is that under the ‘quit-rent’ system, the former could pass down their registered plots under customary law. Registered plots could be inherited. This presented a problem for those theorists who talked about ‘communal land’. Any family that had a plot could hold on to it perpetually, as long as they paid rent annually. This surely was no model of communally owned land.

The incorrigibility of the ‘communally owned land’ thesis, as opposed to the redistribution of land through kinship units, persists unabated in spite of the fact that theorists such as Claude Meillassoux and Pierre-Philippe Rey have written persuasively about the ‘lineage mode of production’, to which the notion of prestige goods is critical to an understanding of the social reproduction of lineages.37 Mafeje contends that whether one is talking about white farms or the rural areas, cattle among South African peasants represent prestige goods, rather than property or means of production. As such, cattle are instrumental in lineage reproduction insofar as they facilitate, inter alia, issues of lobola or bride wealth. This invites questions about the role of livestock in subsistence farming and reproduction of labour.

In South Africa, the two do not necessarily coincide. Subsistence is met through cultivation of crops or wage labour. Livestock only entail means of lineage reproduction or are instruments of production. A related point is that what is usually owned communally in South Africa is grazing ground, not arable land as such.38

When Wolpe wrote about ‘a development of classes in the reserves’ he missed the fact that the possibility of such a process was thwarted by the Land Act of 1913, which was compounded when paramount chiefs, through the Bantu Authorities Act of 1951, were given farms as bribes by the state and thereafter bantustan government ministers helped themselves and their cronies to large portions of land. Still, this need not entail a growing land-owning class. Mafeje argues that ‘to conduct class analysis we do not have to invent classes’.39 The general lessons of this discussion are that a theory not adequately sensitive to concrete realities, however progressive, is likely to be as dangerous as its reactionary counterpart. Moreover, although Mafeje is advocating Marxism as the best answer to bourgeois social sciences, he is nevertheless willing to repudiate its categories if they do not accord with concrete realities. In saying this, I am not suggesting that Mafeje was an empiricist. Rather, I am saying that Mafeje took seriously ethnographic detail and the sociology of knowledge.

On the epistemological break and the lingering problem of alterity

Although anthropology has been criticised by a number of scholars located in different parts of the world, it has not yet dispensed with its problem of alterity – the ‘othering’ or the ‘epistemology of subjects-objects’ as Mafeje puts it. Reasons for this incorrigibility of alterity in anthropology go beyond questions of theory to speak to the sociology of knowledge. Knowledge making is as contested as politics. Mafeje says that epistemologies can be changed (though he does not specify the grounds under which such changes occur) and paradigms can be done away with. He is quick to point out that it is dangerous to assume that knowledge is a result of free inquiry. As far as Mafeje is concerned, new knowledge is usually won through struggle. In his discussion paper Studies in Imperialism, he writes: ‘The requirements of social reproduction predicate that every society sanctions only such activities as are consistent with its overall mode of existence. Intellectual enquiry is no exception to this rule.’40 Those who, like Mafeje, identified Eurocentrism in the social sciences have earned themselves labels such as angry, polemical or combative – once they have received these labels, they need not be taken seriously by the academic orthodoxy. Their ‘anger’ is managed by ignoring them. Social scientists who subscribe to the notion of value-free inquiry often miss the point that lived experiences play a crucial role in how one perceives the world and therefore how one constructs knowledge. Indeed, with characteristic eloquence, Mafeje argues: ‘The separation between intellectuality and sociality is a result of European prejudice which we need not share. Intellectual activity is intrinsically social both in its constitution and in its practice. It can be stated emphatically that what puts intellectual issues on the agenda is social praxis.’

Mafeje continues: ‘It would seem that intellectual systems are capable of a clean epistemological break.’41 For example, there is no necessary affinity between Marxism and positivism or idealism. This raises the question of whether intellectual systems grow by accretion or by epistemological ruptures. If the latter were true, it would be difficult to explain why and how Mafeje was evaluating anthropology as late as 2001, when he and others had already done so in the 1960s and 1970s. Mafeje’s repudiation of anthropology does not translate into its repudiation by all Africans, or even most Africans. This speaks precisely to the view that earlier analyses of anthropology do not necessarily entail a complete break with the discipline.

Mafeje argues emphatically that ‘epistemological ruptures in sciences as well as in other forms of knowledge are usually preceded by crises’.42 This is analogous to the Leninist notion of a ‘revolutionary situation’, which constitutes the necessary (though not always sufficient) condition for a revolution proper. Crises in the social sciences had long been identified by Mafeje, Magubane and others. The question was why this had not led to an epistemological rupture – particularly in Africa. Knowledge making in and about Africa was still very much centred in the West. Therefore, revolutionary crisis was a necessary but not a sufficient condition for a rupture. Revolutionary crisis in the social sciences had to be understood in the wider sociological context, which informed knowledge making – the working example being the skewed relations between the global North and the global South. Mafeje observes that ‘social crisis occurs in society when the requisite processes of social reproduction cannot be attained by normal means i.e. means which are presumed to work because they have done so before’.43

It is still not obvious, however, whether Mafeje believed that, in spite of the analyses of the 1960s and 1970s, the social sciences had reached a point of an epistemological break. And it is not clear either whether African scholars missed the opportunity to capitalise on the momentum of the said crisis. Elsewhere, Mafeje argues that although social studies in African universities continued to be organised along disciplines, the critical studies of the late 1960s ‘played havoc on disciplinary boundaries’.44 He maintains that of all the social sciences that were subject to critical analysis, anthropology never fully recovered and underwent a crisis, particularly in the post-independence period.

There is a lot to tease out and reflect on in Mafeje’s argument. First, it appears that anthropology has recovered from the crisis of the 1960s – Mafeje’s re-evaluation of anthropology in the 1990s and 2000s suggests this. Second, it could be argued that although other disciplines were assessed by radical social scientists in the 1970s, they have survived the onslaught. Indeed, scholars of the global South would not now speak of Eurocentrism and the need for epistemological and curriculum decolonisation if the situation were as severe as Mafeje presented it. If anything, analyses of anthropology reflect a particular epoch, both intellectually and sociopolitically. In the age of neoliberal complacency there is now, more than ever, a need to revisit those critiques that have been overshadowed by conservative scholarship. To be fair, Mafeje was reflecting on the state of affairs in the 1980s and much has happened since. The consolidation of conservatism, both intellectually and sociopolitically, by an academic orthodoxy the world over, implies that what radical social scientists are pursuing now is the recovering of intellectual nerve about which Jimi Adesina speaks, rather than an epistemological break proper.45 Mafeje said that one had to make a distinction between an epistemological break and the emergence of a new or alternative theory. Although methodologies can produce valid results, each methodology is limited by its underlying assumptions. According to Mafeje: ‘It is when such underlying assumptions are found not to apply to an increasing number of observable instances that a theoretical crisis occurs.’46

The nagging question was why and how an epistemological break – or even an alternative theory – was reversed so that the gains already made lost their relevance. Mafeje’s response to the question:

In the social sciences the ideological component, which earlier we referred to as intellectual prejudice, appears to be incorrigible, ultimately. For instance, irrespective of the evidence that might be brought to bear, there is no way in which social scientists in the imperialist camp could be persuaded that imperialism exists and is a major problem of development in the Third World. It is also noteworthy that it was only possible to convince the practitioners that there was colonial anthropology after colonialism had been fought and defeated.47

Formally, colonialism may have been fought and defeated but anthropology has not and, as Mafeje points out, ‘while it is true that “modernisation theories” have been discredited, to assume that they have disappeared would be dangerous complacency’.48 Although the social sciences may be deemed technical subjects, their theories do not change because of technical reasons that are inherent or internal to the social sciences. Revolutionary changes in the social scientific theories usually stem from social changes or crises. This means that the social sciences, more than the natural sciences, ‘are strongly ideologically-conditioned’.49 This notwithstanding, it is not always clear when such social crises occur or where the point is at which social problems amount to a societal crisis. Mafeje argues that social problems amount to a social crisis when they are no longer amenable to practical and theoretical rationalisations.

One way of objecting to Mafeje’s argument would be to point out that it broke the old philosophical taboo on deriving ‘ought’ from ‘is’ – that X exists, or will exist, is no sufficient justification for its moral goodness. Such an assumption commits the naturalistic fallacy. Substantively, however, such an objection may do little to dent the necessity of the societal crisis for historical changes, for it seems extraordinary that a rupture could simply come via spontaneous combustion. That notwithstanding, the moral or inherent goodness of societal crisis is still in doubt. This is so because the crisis in the social sciences in the 1970s has not necessarily led to an epistemological rupture. The incorrigibility of alterity in anthropology is a case in point. Yet it might be better to seek ruptures at meso levels instead of the level of totality of the social sciences. The works of Oyeronke Oyewumi on gender are representative of an epistemological rupture in the global discourse of gender, particularly The Invention of Women.50

Although Mafeje was critical of anthropology as a discipline, he understood very well that all of the bourgeois social sciences are deeply implicated and he attempted to show that anthropology must be understood as consistent with the growth of functionalism and colonialism more generally. Anthropology, he said, was founded on studying the ‘other’. Quite why the practice of othering persists even to this day is a question that exercised Mafeje a great deal. The lingering problem of alterity, it should be remembered, continues years after anthropology had gone through a crisis as a result of critical evaluations by Mafeje and other radical social scientists.

Three issues generally emerge from Mafeje’s investigation: (i) the self-identity and role of African anthropologists in the post-independence period; (ii) the question as to whether there can be an African anthropology (not anthropology in Africa) without African anthropologists; and (iii) the question as to whether authentic representation on the part of African anthropologists would entail a ‘demise of Anthropology as it is traditionally known’.51 The general point is that deconstruction carries little weight if it does not entail reconstruction: negation without affirmation is meaningless. But attempts at reconstruction have always been difficult since much of it was conducted in the North, with only a few exceptions from the South. Mafeje captures something of this when he says: ‘From a historical perspective, it could be said that in the main African anthropologists did not anticipate independence in their professional representations. What this would have entailed is an anticipatory deconstruction of colonial Anthropology so as to guarantee a rebirth or transformation of Anthropology.’52

In a review of Mafeje’s Anthropology and Independent Africans, Godwin Murunga notes that in making these remarks, ‘Mafeje overlooks the work of Okot P’Bitek in that the difference between [P’Bitek] and other African anthropologists is that P’Bitek declared anthropology dead in Africa and “redirected his energy into literature to the extent of championing the field of oral literature”’.53

In spite of the said deconstruction, or the so-called crisis anthropology went through, attempts at reconstructing or otherwise burying it altogether proved impossible. The lingering problem of alterity is a case in point. Elsewhere, Mafeje suggested that anthropology was on its deathbed, but not yet dead. Although Mafeje recommended in his earlier works that critical evaluations must be directed at all the imperialist social sciences, Helen Macdonald, in her article subtitled ‘Subaltern Studies in South Asia and Post-Colonial Anthropology in Africa’, has pointed out that Mafeje revised his position somewhat in the light of responses from his critics.54 The most important thing, however, is that Mafeje made a plea for non-disciplinarity, a case he had been building as far back as the 1970s with the essay ‘The Problem of Anthropology in Historical Perspective’.

The issue turns on transcendence of disciplinarity as against the unification of disciplines. Adesina takes issue with Mafeje’s rejection of disciplinarity and epistemology. He argues that not only did Mafeje mistake issues of pedagogy for those of research, but he also mistook epistemology for dogmatism. Adesina advances a well-considered, albeit brief argument against Mafeje, but it needs to be said that Adesina wrongly imputes to Mafeje the concepts of interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity.55 Adesina’s claim is that scholarship is interdisciplinary ab initio. No societal problems are purely social or purely economic. In terms of research, societal problems require one to tap into other disciplines. In Adesina’s view, Mafeje’s argument appeared misdirected. As regards pedagogy, Adesina argues, the danger with interdisciplinarity is that it leads to training students who have no methodological grounding in any discipline. This is a valid argument. But there is something to be said about Mafeje’s advocacy of non-disciplinarity rather than inter- or transdisciplinarity. Mafeje’s proposal has far-reaching consequences for both teaching and research.

The non-disciplinary approach makes proposals or has implications not only for transcendence of Euro-American epistemology and methodology, but necessarily holds true for teaching purposes as well. It has to be so, for the simple reason that if disciplinarity, such as is conventionally known, is to be transcended or otherwise dismantled for the purposes of knowledge production/research, the same must be true for teaching purposes. Thus Mafeje’s new social science ought to entail new teaching or training methods as well. Mafeje did not use the concepts of interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity affirmatively. In recent articles Dani Nabudere and Helmi Sharawy both feel that Mafeje did not transcend the Western knowledge archive;56 indeed, Mafeje ‘does not uphold the idea of the End of Anthropology in order to liquidate an epistemological order, but rather to put in its place a more appropriate alternative to the concept, which, in his opinion, leads to anthropological theorising of another kind’.57 Again, here the question seems to turn on whether Mafeje succeeded or failed, and not on his attempt to liquidate an epistemological order, which is clear – the search for an epistemological rupture is a case in point. Mafeje’s interlocutors are correct in claiming that he did not transcend the Western knowledge archive, but their reasoning is faulty. For example, they say he advocated interdisciplinarity. That is incorrect. A much more suitable example of Mafeje’s failure to transcend the Western knowledge archive is his appeal to Marxism as the best anthropology there is. In this regard, Sharawy and Nabudere are onto something. But this is a position Mafeje modified in his later commentary on the social sciences, since he no longer appealed to Marxism per se. For example, in Anthropology and Independent Africans, Mafeje maintains that ‘of interest to us in the present context is that all what is said above was not anthropological … Nor was it interdisciplinary … It was non-disciplinary.’58 In his response to his critics, ‘Conversations and Confrontations with My Reviewers’, he argues that ‘interdisciplinarity leads to theoretical hiatus. It will require a major epistemological breakthrough as good as positivism which instigated the rise of the disciplines and led to the fragmentation of social theory to achieve any coalescence.’59 Earlier he had argued that ‘the attack on Anthropology was heartfelt and justified in the immediate anti-colonial revulsion. But it was ultimately subjective because the so-called modernising social sciences were not any less imperialist and actually became rationalisations for neocolonialism in Africa, as we know now. However, the important lesson to be drawn from the experience of the African anthropologists is that Anthropology is premised on an immediate subject/object relation.’60

This is consistent with Mafeje’s stance on the social sciences generally and on anthropology in particular. In the light of criticisms, however, Mafeje slightly revised his position. On the racist nature of anthropology he was consistent, but on the question of Eurocentrism in other disciplines he backtracked – an inconvenient afterthought that could have easily cost him the debate. Mafeje’s belated concession that the other social sciences are less Eurocentric is a blunder that nevertheless does not diminish the overall substance of his assessment of the social sciences. Perhaps Mafeje might have been justified in making such a concession when one considers some of the pioneering works of African social scientists – Oyewumi’s work in social science, for example, is hardly Eurocentric and Akinsola Akiwowo’s sociology is just as far from Eurocentric.61 Similarly, Ifi Amadiume’s works fall within the social sciences but she rejects anthropology in favour of social history.62 Nor are Cheikh Anta Diop’s works in historical sociology Eurocentric. The point is that Mafeje was making a distinction between bourgeois Eurocentric social science and social science as such. His argument is that it is difficult to conceive of anthropology without racism (epistemology of alterity) whereas one can think of sociology or economics without being, ipso facto, racist. The anthropological inquiry is premised on the researcher as ontologically distinct from the subject of their inquiry, whereas Western sociologists study the subjects of their inquiry as ontologically similar to themselves.

Still, this does not explain why social scientists from the global South still speak today of epistemological decolonisation or curriculum transformation. That there exists less Eurocentric social science from African scholars is no reason to suppose that the social sciences are not overwhelmingly Eurocentric. To assume that the social sciences cannot be transcended, in the manner of Mafeje’s non-disciplinarity, is to assume that the social sciences, as they are currently known, are transhistorical – they have been there since the beginning of time. That is not the case. Anthropology, for example, is the child of colonialism and imperialism. Mafeje’s later position on anthropology centred on the lingering problem of alterity, years after the discipline underwent its epistemological crisis. In critically evaluating anthropology, and the social sciences generally, Mafeje was in search of an epistemological rupture and therefore new paradigms. Regardless of whether Mafeje backtracked in reviewing all of the social sciences, the substance of his analysis remains. He was not assessing anthropology (and other social sciences) for its own sake; he sought to replace it with something else. Hence ‘deconstruction’ and ‘reconstruction’.63 He saw such an undertaking as being accomplished through sound research and deep familiarity with one’s ethnography and he says, for example: ‘As our study on the interlacustrine shows, without a serious return to the study of African ethnography, it is not likely that any important breakthroughs will be made in African social science.’64 What exists currently is anthropology in Africa as opposed to African anthropology. Mafeje uses the term ‘ethnography’ in two senses. First, ethnography as he conceives of it has sociocultural connotations – it is in fact his preferred substitute term for the nebulous concept of culture. Second, by using ‘ethnography’ he is referring to ‘non-disciplinarity’ and it became a substitute for the social sciences as they are conventionally known.

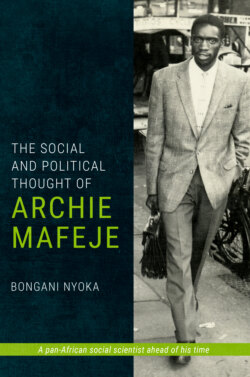

Figure 3.1. Map of interlacustrine kingdoms. Drawn by Patrick Mlangeni