Читать книгу Shell-Shocked - Bonnie Honig - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

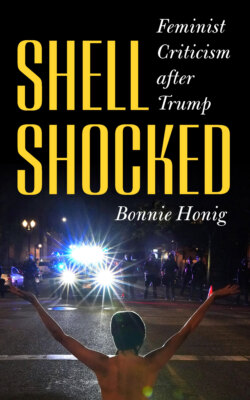

ОглавлениеPreface

Trump will be gone by the time you are reading this book, but Trumpism will still be around in one form or another. Why am I so sure? Because like many things Trump, Trumpism is just a name slapped onto things that were already out there.

Trump gave a name to a toxic flambé of misogyny, xenophobia, and racism and then lit the flame. Together with a weakness for celebrity, these are America’s “pre-existing conditions.”

When Covid-19 hit some American communities especially hard in the first wave of 2020, the virus served as a barometer of inequality. The so-called co-morbidities of asthma, diabetes, and being overweight are often the results of one’s living in toxic environments: food deserts with polluted air, poisoned water, and poor ventilation. The real pre-existing conditions here are racism and inequality, and they take their toll.

For Trump, Americans’ asymmetrical vulnerability to the virus was not a condemnation of white supremacy but a vindication of it, further evidence that white people are biologically superior to those of other races. He attributed his own quick recovery from Covid not to the exceptional (publicly funded) care he received at Walter Reed Hospital but to his superior genetic endowments. His youngest son tested positive, too, but Barron, whose name was one of Trump’s aliases in the 1980s, never got sick. Reporting on his son’s seeming immunity, Trump proudly noted that his son was tall. That seemed strange, since the virus is indifferent to height. But this was Trump’s way of celebrating genetic inheritance and taking credit for it. Why not? He had slapped his name on Barron too.

White supremacy kills. Minimizing the harms of the virus and touting white immunity to it cost hundreds of thousands of lives from every corner of American society. As one young woman put it, talking about her father who was lost to Covid, “his only pre-existing condition was believing in Donald Trump.”

During the final weeks of his 2020 campaign for reelection, Trump accused doctors of inflating the number of Covid cases to make money. Shocked to be called profiteers when they had sacrificed so much, doctors turned “Dying not lying” into a hashtag and shared memoria of health workers who had lost their lives to the virus. Many had been let down by the social contract of care and concern and were left to repurpose garbage bags for protection in the absence of proper equipment that the federal government was slow to provide.

I write in the final hours before Joe Biden is named president-elect and Kamala Harris vice-president–elect. Now it is poll workers, counting the votes in the 2020 election, who are at risk, as they tabulate the count in several states. They are at risk not only from the virus, which continues to rage through the population, but also from Trumpism, which, raging through the body politic, feverishly foments conspiracies that send armed militia members and Boogaloo Boys to the counting places. One poll worker in Georgia had to go into hiding after being falsely accused of throwing out a ballot. The Republican City Commissioner of Philadelphia reported that his office was receiving death threats for counting votes. The lives of election workers are endangered when the idea of public service is discredited. Those who think poll workers are just in it for themselves find it easy to suspect they are up to no good. Like a virus, this cynicism about public service will seem to come and go in the coming years, sometimes spreading like wildfire, then embering and fooling us into thinking it has safely disappeared—like a miracle.

Trumpism, which this volume analyzes in a series of short essays written from 2016 to 2020, will have other names in the future, just as it has in the past, but what it names will not go gently into that good night. It names a kind of male entitlement for which it feels like freedom to just be able to say what you think and grab what you want. But freedom is not impulsiveness, and it cannot take root in division.

The opposite of impulsiveness is self-restraint. Some call that dignity, which is what Joe Biden said he wanted to bring back to Washington. Real freedom lies in lifting ourselves collectively to heights that were once unattainable. It is not about being superior to others, nor is it merely a matter of personal virtue. It is about uniting because there is strength in numbers and power in union. And the affect of freedom is not rage; it is joy, which is what Kamala Harris said she wants to bring back to Washington.

The affect of the Trump presidency was not joy but shock. Shell shock was the deliberate result of the constant tweeting, daily controversies, and calls for investigations, all of which contributed to a four-year-long ambient rumble of rage, gaslighting, and resentment. Public norms and institutions, which had been tested and violated before, were now openly dismantled and commandeered to avoid accountability.

The power of shock is in its seeming implacability. Shock overwhelms a people’s senses; it breaks apart individuals, communities, and institutions; and it paralyzes us. Flooding the airwaves with lies presented as alternative facts, shock attenuates the practice of public deliberation and destroys the quiet of critical reflection. It is disorienting. Instead of walking with purpose, we find ourselves stumbling.

I argue in this collection that the kind of attention to detail practiced by feminist criticism can help us find patterns in the chaos of shock and points of orientation in the miasma. Close reading helps loosen the grip of shock or at least prevent its further tightening. It brings discernment to the disarray. Criticism brings us together to share impressions, develop collaborations, and compare perspectives. Feminist criticism tears at the fabric of America’s pre-existing conditions and loosens its binds.

Then, one day the grip of shock is broken, and joy marks the moment and helps reset our bearings. It happens not like a miracle, but like the product of years-long hard work, much of it done by Black women, union members, the Latinx community, and groups like Indivisible and others in whose names chapters were set up all over the country. For months or years, people woke up every day to register voters, empower people, fight suppression, overcome division, organize communities, encourage dance at protests, and play music outside election halls. Seeing to the details and committing to the everyday, these actions created a public united against America’s divisions. They gave life to the public option: a kind of collective insurance that commits each to all in times of hardship and leaves no one behind because of their so-called pre-existing conditions.

And then, the count is complete, and the shock that once seemed implacable is replaced by implacable procedure, the seemingly unstoppable machinery of the peaceful transfer of power. At other times in other moments, that machinery overwhelmed the will of the people. But not this time. Just now, as I continue to write, the election is called for Biden–Harris, and thousands and thousands of people everywhere have gathered spontaneously in the streets, joined in joy on an implausibly beautiful and sunny November day. We are plural, we are often disagreeable, but today, anyway, many of us are dancing in the public streets. There is still so much work to do, but no one is gassing or brutalizing the people today and the view from here is almost fine.

Bonnie Honig

Warren, VT

Nov. 7, 2020