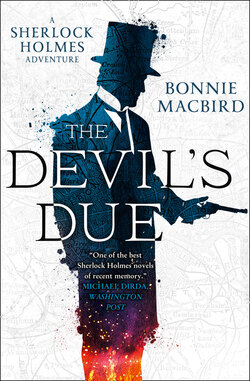

Читать книгу The Devil’s Due - Bonnie Macbird - Страница 14

CHAPTER 6 The Greater Goodwins

ОглавлениеMycroft heaved himself to his feet. ‘Welcome, gentlemen! Sherlock and Doctor Watson, I have invited this illustrious duo who have something to impart.’ Two foppish and very handsome young men spilled into the room on a cloud of cigar smoke, laughter, and the scent of expensive cologne and hair oil.

We rose as Mycroft continued. ‘May I introduce to you brothers Andrew and James Goodwin, viscounts both, and members of the House of Lords.’

‘I say, Mycroft, is this some kind of Game Day at your club?’ cried the taller of the two, garbed in an exquisitely tailored but slightly anachronistic deep blue velvet suit. ‘Everyone here seems to want everyone else to shush!’ He was a dark-haired gentleman, his long, curly locks coiffed in a Byronic style, giving a bohemian, artistic impression, contrasting with a coiled energy.

‘Yes! We were shushed five times – no six – between the entrance and this room,’ drawled the shorter of the two, whose deep green velvet attire resembled his brother’s. His appearance was differentiated by stylishly cropped hair, groomed straight back from his face and oiled to shine like patent leather.

As strange as their styles were, their suits were expertly tailored, complimenting each man’s physique. Sportsmen, too, I decided. Two odd, if very rich, ducks.

‘Silence is a policy of the club, gentlemen, except for this room,’ said Mycroft. ‘Do come in and meet my brother, Sherlock Holmes, and his friend and colleague, Dr John Watson.’

‘Sherlock Holmes! The Demon Detective!’ cried James, the man in green. ‘And his little friend, the writer!’

As if in response to my social discomfort, the taller man drawled, ‘He is an army doctor, James, not a “little friend”. Relax, gentlemen, we do not bite.’

‘Dr Watson! I say, are you a medical doctor, then? So sorry!’ cried the shorter. ‘Because I have a toe—’

‘James, not now!’ implored his brother, and they both laughed.

At Mycroft’s gesture, the brothers claimed the seats on the sofa we had just vacated, the two of them taking up its entire long length, reclining as though they were at home in their sitting-room.

Holmes and I found other seats, then waited patiently as the two young men called for coffee and cigarettes, lumps of sugar, napkins and biscuits, clean ashtrays, Scotch and Claret, causing the attendant to scurry about, bringing in item after item, only to be sent out again.

Mycroft smoked his cigarette patiently and seemed to take no notice of this odd show. Holmes, however, got up and moved once again to the window, irritated.

I studied them in more detail. Andrew, in blue, appeared to be older, and leaned back, languidly regarding Mycroft through a haze of cigarette smoke, a sardonic smile upon his smooth features. He was clearly a man used to privilege, and rarely challenged. A keen intelligence shined through his relaxed demeanour and I would warrant the man missed very little.

By contrast, his brother James, in green, was highly strung, as though an electric current animated him always, his dark brown eyes glittering in amusement and interest. He gestured with quick movements, smoothing his patent leather hair, flicking ash from his cigarette, sipping from his Claret, taking in the room and us in darting glances. He, too, seemed intelligent, with that air of entitlement possessed by the very rich.

They were a curious combination. I had heard of them, of course. Two of the youngest members of the House of Lords, they were influential and wealthy almost beyond compare. They shared an enormous house near Grosvenor Square, famous for its parties.

These frivolous and foppish first impressions were carefully cultivated, I presumed, as I had also read they had recently championed a major bill in Parliament with new protections for factory workers, against considerable opposition from their own party.

‘Shall we begin?’ said Mycroft. ‘Sherlock, do come and join us. They have news which will be of interest. Mr Goodwin, may I call you Andrew, if only to differentiate you from your brother James?’

‘Oh, indeed, do use our Christian names. Everyone does, for that very reason,’ said Andrew Goodwin.

‘Andrew, then, please advise my brother Sherlock and Dr Watson what you told me this morning.’

‘Oh, yes,’ said Andrew taking a healthy sip of his whisky. ‘Ah, very good, this. We must get some for the house. What is it?’

‘A self whisky. Glenmorangie from Tain. And now your news, please,’ said Mycroft.

‘Tell them, Andrew,’ said James.

‘Yes. Those recent murders. Anson. Clammory. And then that poor man stabbed by his own son!’

‘Danforth. What about them?’ asked Holmes.

‘They are all Luminarians,’ added James.

‘Were, James, were!’ said Andrew.

‘Interesting,’ said Holmes returning to sit with the group.

‘What is a Luminarian?’ I asked.

All eyes swivelled to me. The Goodwin brothers shared a smile.

‘It is a very secret organization, Watson,’ said Holmes. ‘Not unlike the Freemasons, who also exist to promote good works. However, the Luminarians do not spring from the building industry. They are, to a man, a breed of wealthy do-gooders, all self-made, who use their money and influence to “bring light to the world”. Hence “Luminarians”. An organization started by the two of you, I understand. That is really all I know.’

Andrew and James stared at Holmes in surprise.

‘But you know quite a bit. How is that?’ James blurted.

‘It is my business to know London intimately,’ said Holmes.

James laughed and looked at his brother. ‘Well, if Mr Holmes begins to reveal what I did intimately in our mutual study at two o’clock early this morning, I’ll have him down for a witch.’

‘What is a male witch called, by the way?’ said Andrew.

‘A warlock,’ said Holmes, matching their good humour with an uncharacteristic smile of his own. ‘I have been called the Devil, but never a warlock. And no, I have no eyes in your study. How does one become a Luminarian? Does one apply and need a second? Do you induct new members?’

‘It is not a membership per se. There is no applying or formal induction. It’s more of a … bestowing. Kind of like the Queen’s honours,’ said James Goodwin. ‘Not quite a knighthood, but …’

‘Oh, James! Being dubbed a Luminarian is our honour, given by us, to a very lucky few,’ said Andrew.

‘And the benefits of this honour?’ asked Holmes.

‘None really. Just the satisfaction of the honour. A certificate, I suppose suitable for framing.’

Both men laughed at the thought. ‘Oh yes, and a rather nice pin,’ said James.

‘Names, please,’ said Holmes, removing a small notebook and a silver pencil from his pocket.

‘Oh, we couldn’t,’ said James.

Holmes sighed. ‘If three Luminarians have recently met untimely ends, it would be prudent if you would provide us a list of members. In case this is a … trend.’

The brothers exchanged a glance.

‘Honorees, not members. What my brother means is that we really couldn’t,’ said Andrew. ‘There is no formal list. Besides, no one knows of this group but us.’

‘My brother knew,’ said Mycroft.

‘The recipients of this “honour” know. And those who see the pins,’ said Holmes.

‘I was joking about the pins. And the certificates.’

‘What about meetings?’

‘None. It is not a society in that sense,’ said Andrew.

‘No lunches? No annual Christmas dinner?’ persisted my friend.

‘You are being facetious. No, just the honour. Mycroft is a Luminarian, by the way.’

‘You are forgetting that I declined,’ murmured Mycroft, pouring himself a Scotch.

‘How is this honour bestowed?’ asked Holmes.

‘At a private ceremony at our house,’ said James. ‘Plenty of champagne.’

‘Of course, we invite the Luminarians thereafter to our parties,’ said Andrew. ‘Usually.’ Neither Holmes brother reacted. ‘It is a rather coveted invitation,’ he added.

‘Indeed!’ I blurted out.

The group turned to look at me.

‘I, well, my wife Mary enjoys reading about your parties. In the papers. They have quite a reputation. The food. Music …’

The four men stared at me. I felt myself colouring.

‘Well then, surely you should come sometime. Dr, er … sorry, I have forgotten.’ said James.

‘Dr Watson. Make a note of that, James,’ said Andrew.

‘Please recreate the list for me, the best you can, then,’ said Holmes, beginning to lose patience.

‘Oh, I can’t think,’ said Andrew with a wave of his very white hand.

‘Neither can I,’ added James. ‘We have been up all night working on a bill we will bring to Parliament next month. Lunatic law. Inhuman as it stands. Oh, and deciding on the menu for tomorrow.’

‘And who to invite shooting in the country next week,’ added Andrew.

‘It is quite important. Please write down those you can recall.’ Holmes extended his notebook and pencil to Andrew, who hesitated, then dashed off a few names, showed the list to James, who added one more. James handed the notebook back to Holmes.

‘These are all we can think of at the moment,’ said James.

Holmes looked over the list. ‘Please try to remember more and send the rest of the list to me later today.’

‘We shall,’ said Andrew. With a few more goodbyes, the two brothers departed as chaotically as they entered.

As the door closed behind them, Holmes eyed his brother Mycroft with some amusement. ‘You turned them down, did you?’ he murmured.

‘I have turned down any number of honours, Sherlock,’ said his brother. ‘Now get to work on that list.’

‘Why are they holding back on naming its members?’ asked Holmes. ‘Do you have a list?

‘No. And I do not think they are holding back. This is merely a hobby, not something they take seriously. Now, do apply yourself.’

‘Doing what, Mycroft? I am not equipped to provide protection for seven or eight random men in London, nor can I detect in advance of a crime.’ He glanced again at the list. ‘An M, an R, an S and a V. There is no B here. Perhaps this Luminarian connection is a coincidence. Ah, but here is an earlier letter. F. How odd. Oliver Flynn!’

‘The playwright!’ I exclaimed. ‘Mary and I loved Lord Baltimore’s Snuffbox. Brilliantly funny!’

‘Watson, please,’ Holmes said. ‘Mycroft, I have discovered that Flynn is connected to a French anarchist group here in London. I have infiltrated them and, in the guise of an artist, I have been invited to a party in three days’ time. I expect—’

‘Oliver Flynn is well-meaning, and has sympathy with the downtrodden,’ said Mycroft, ‘but he is rather misinformed about the methods he is helping to fund. Socialism is one thing, anarchy another.’

‘Oliver Flynn with the anarchists?’ I exclaimed. ‘This seems improbable! Why would a famous playwright and bon vivant fund bombers?’

‘Odd bedfellows. But yes, Watson. I shall explain later,’ said Holmes. He turned to his brother. ‘What of his connection to the Goodwins?’

‘Social, I presume. He gets about. If our alphabet theory is correct, Flynn, as an F, could be a target quite soon,’ said Holmes’s elder brother. ‘I shall use my influence to convince him to take a sudden vacation. That should keep him safe while you pursue the alphabet killings, Sherlock.’

‘Mycroft! The anarchists are my current focus. Flynn’s party is vital to my investigation.’

‘I know about the trail you follow, including that grocer in Fitzrovia. Those anarchists are terribly dangerous, Sherlock. They are inexperienced young men fooling with explosives beyond their capabilities, driven by youthful fervour and misplaced idealism. One will blow himself up accidentally, mark my words. Stay away.’

I thought that odd. In the past Mycroft Holmes had shown he was more likely to send his brother into danger than to warn him off it.

‘Your concern is touching, Mycroft. But, no.’

‘Drop it, I say.’

‘Why?’

‘The French have someone on it.’

‘Ah, here we are,’ said Holmes. ‘Tell me it is not who I think.’

‘I am afraid so,’ said Mycroft, ‘The French government adore him.’

‘Not Jean Vidocq?’ I blurted.

Mycroft’s silence was confirmation.

Vidocq was a handsome, arrogant French operative who considered himself a rival to Holmes. He had occasionally joined forced with us but had proven to be a dangerous and unreliable man. Even his name was a sham. Vidocq was no more related to Eugène Vidocq, the famous founder of the French Sûreté, than I was. He had merely adopted the name for its cachet. The man was responsible on a previous case for pushing me down a flight of stairs!

‘Jean Vidocq is a scoundrel,’ I said. ‘Not even terribly competent.’

‘He is useful, gentlemen. And you forget, he is well respected in France,’ said Mycroft.

I was unconvinced.

‘I will not drop the anarchist investigation, Mycroft,’ said Holmes. ‘I am close to cracking a group via that grocery in Fitzrovia, and I intend to connect them to Flynn.’

As we stood to leave, Mycroft pinned his brother with a look that would strike fear into most. ‘Drop it, I say, Sherlock, and attend to the Alphabet Killings. One by one, men who are creating great works of charity are being eliminated. Think of the loss to those in need. Think of the greater good.’

At that precise moment, a page came in, approached Mycroft and whispered in his ear.

‘What is it?’ asked Holmes.

‘Another bomb went off. The French. Somewhere near Leicester Square.’

‘Anyone killed?’

‘Five dead. Six wounded.’

Silence as we took this in. Finally, Holmes said, quietly, ‘The greater good, Mycroft? Really? I will choose my own cases, and investigate however I please, you and Titus Billings notwithstanding.’

We turned to depart, but Mycroft was not finished. ‘Sherlock, that Zanders fellow – remedy that. You know better than to inflame a journalist. You are losing your touch.’

‘Perhaps you lack a challenge yourself, Mycroft, and are bored? Here is one for you. Take care. If it is an alphabetical series, H follows E, F and G. The scythe draws nearer, perhaps to you, brother.’

Holmes did not pause for the answer but stormed out of the door, myself following. I was always happy to depart the Diogenes Club.