Читать книгу Nonstop - Boris Herrmann - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

BY JOCHEN RIEKER

Оглавление“THERE ARE TWO TERRIBLE EXPERIENCES THAT A PERSON CAN MAKE: NOT FULFILLING THEIR DREAM, AND HAVING FULFILLED IT”

BERNARD MOITESSIER,

LA LONGUE ROUTE

It’s still very quiet this Saturday morning in the country house in Longeville-sur-Mer, half an hour’s drive southeast of Les Sables d’Olonne. In the remote, slightly dusty AirBnB rental with Ikea guest beds, Team Malizia has set up its headquarters for the week, far away from the hustle and bustle of the Race Village.

The fresh north-westerly wind, which will reach gale force in the Bay of Biscay in the afternoon, is pushing through the old doors and windows and moaning softly in the chimney. The heating gave up during the night, and the house is noticeably cooler this morning. Just a few hours ago, champagne corks were flying and the rooms were filled with excited chatter and laughter.

There’s a hint of a hangover feeling as Boris Herrmann comes down the creaking stairs at seven-thirty in jogging bottoms and fleece jacket, his features still a little crumpled with sleep and bearing the traces of having spent three months alone at sea. But there’s no reason to be down this morning, not at all!

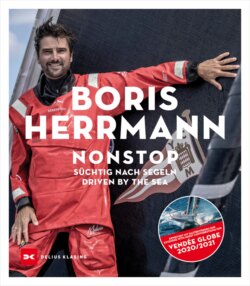

Less than two days ago, on 28 January at 11.19 am, he finished the Vendée Globe, the hardest regatta of them all: single-handed, non-stop around the world. This was the goal he had been working towards for many years, giving everything he had, including the last of his savings. A childhood dream finally fulfilled after 80 days, 14 hours, 59 minutes and 45 seconds.

Not only that: Herrmann has written sailing history.

He‘s the first German to take part in the classic ocean race in which barely more than half of the field usually makes it to the finish. He managed this on his very first attempt, hoisting the black, red and gold flag into the hazy January sky on entering the channel of Les Sables.

Taking 5th place in the tightest sprint to the finish ever seen in the Vendée Globe, the man from Hamburg is now unquestionably one of the best solo skippers in the world. This was the position he had hoped for before the start, but only made this public shortly before Cape Horn. Finishing the race was his primary goal, as he told Yacht in an interview, with the result “depending very much on fortune”.

NOW HE HAS DONE IT

Boris Herrmann, already long established as by far Germany’s most successful ocean sailor, has fulfilled and exceeded all expectations. Even the German Chancellor congratulated him on his “fantastic achievement”. In Germany, Angela Merkel let him know, “we were right there with you”. And even this is an understatement: half of the nation was electrified.

That same day, Niels Annen, Secretary of State in the Foreign Office, nominated Herrmann for the Federal Cross of Merit. Drawing comparisons with the “summer fairytale” of the 2006 World Cup in Germany, some observers have dubbed this the winter fairytale that had the country holding its breath. Newspapers, magazines, TV news, sports programmes and talk shows will be celebrating the finish like a victory for weeks to come.

Almost 20 years after the triumph of Team Illbruck in the Volvo Ocean Race, sailing has finally experienced another great moment, a Boris moment, greater than nearly all the other successes to date – perhaps also because things were not looking so good for quite a while, with this ninth Vendée Globe so punishing for its participants, and Herrmann needing a long time to move up in the race, and because the collision with a fishing trawler in the night before the finish could have dashed all hope.

His ambivalence is palpable this morning, with the orange-red plumes and phosphorous fumes from the smoke fountains and torches marking his arrival in the channel of Les Sables now only a memory. His team has been celebrating with him for two nights, even as he nodded off in his chair and took himself off to bed soon after. His abrupt landing in his new, old life must make him feel like he’s in a film that has been speeded up to an uncomfortable degree. Or like a sudden emergency brake.

LOOK BACK FORWARD

The race – his race – is over. The fight for the highest possible placing, his worries about the boat, being alone, the exhaustion from sleeping in half-hour stretches for weeks on end, interpreting mostly difficult weather conditions, and the sheer mass of all the privations that can hardly be measured – all of this now lies astern. But of course he’s feeling it all still. He has not yet sorted, evaluated, processed and settled it. It will take some time for his head, body and soul to be over all the stress and strain.

“A few weeks” Herrmann reckons. Some former participants talk in terms of months. Four years ago, Conrad Coleman needed “more than half a year”.

Ahead of Boris Herrmann now there lies a new beginning, and an in-between. Less adrenaline, few endorphins, no existential experiences at the limit. But no holiday either, no down time. For him, the professional sailor, the end of the Vendée Globe also means the end of his pay, the expiry of his sponsorship contracts, and the need to develop new prospects for himself and his co-workers.

The world had been cheering him on, up to the day before last. His popularity, increased enormously by his Atlantic crossing with Greta Thunberg, has reached a new height – this will make a lot of things easier. He’s seen as a model athlete in a sport that is still fresh to the media: smart, likeable, honest, telegenic.

However, for the moment these are only possibilities, opportunities, chances – not pay cheques he can use to cover his bills and support his family. This, too, is a reality to which Boris Herrmann has returned.

Marie Louise, known to all as simply Malou, is meanwhile crawling across the cold parquet flooring in her pink romper suit. She didn’t sleep well and was up early. Herrmann’s wife Birte has brought their eight-month-old daughter down to the living room. Seeing her Daddy, she smiles.