Читать книгу Disposable Futures - Brad Evans - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

THE DROWNING

Writing one of the most important personal testimonies on the extreme horrors of the twentieth centry, Primo Levi observes: “Logic and morality made it impossible to accept an illogical and immoral reality; they engendered a rejection of reality which as a rule led the cultivated man rapidly to despair.” Indeed, the tragedy of ideological fascism for Levi is both the forced complicity of victims into systems of brutal slaughter, and the seductions of violence made desirable by those interned to render them accomplices in their own destruction. As he further states, “the harsher the oppression, the more widespread among the oppressed is the willingness, with all its infinite nuances and motivations, to collaborate: terror, ideological seduction, servile imitation of the victor, myopic desire for any power whatsoever.” Central to Levi’s analysis here is the way in which the spectacle of violence becomes a substitute for human empowerment—a last refuge if you will—for those who are already condemned by the system.

Levi exposes us to the depths of human depravity and the dehumanization of our worldly fellows. He also warns us about the dangers of reducing the human condition to questions of pure survival, such that a truly dystopian condition accentuates the logic of violence by seducing the oppressed to desire their own oppression or to imagine a world in which the only condition of agency is survival. Eventually, as Levi points out, the spectacle of violence becomes so ingrained that everybody is infected, to the extent that clear lines concerning morality, ethics, and political affinities blur into what he termed “the gray zone.” If the system strips some lives of all sense of humanity and dignity—the killing of the subject while the person is still alive—so they come to embody what he named “the drowned,” those who remain are forever burdened by the guilt of surviving, the shame of being “saved” from a wretchedness that destroys the very notion of humanity.

Levi’s notion of disposability was rooted in a brutalism in which genocide became a policy and the slaughter of millions the means to an end. What Levi couldn’t have foreseen given the extreme dystopian historical circumstances of his time, however, was that disposability or the notion of intolerable violence and suffering in the twenty-first century would be recast by the very regimes that claimed to defeat ideological fascism. We are not in any way suggesting a uniform history here. The spectacle of violence is neither a universal nor a transcendental force haunting social relations. It emerges in different forms under distinct social formations, and signals in different ways how cultural politics works necessarily as a pedagogical force. The spectacle of violence takes on a kind of doubling, both in the production of subjects willing to serve the political and economic power represented by the spectacle and increasingly in the production of political and economic power willing to serve the spectacle itself. In this instance, the spectacle of violence exceeds its own pedagogical aims by bypassing even the minimalist democratic gesture of gaining consent from the subjects whose interests are supposed to be served by state power.

It was against twentieth-century forms of human disposability that we began to appreciate the political potency of the arts as a mode of resistance, as dystopian literatures, cinema, music, and poetry, along with the visual and performing arts, challenged conventional ways of interpreting catastrophe. We only need to be reminded here of George Orwell’s Animal Farm, Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima Mon Amour, Bretolt Brecht’s The In- terrogation of the Good, Max Ernst’s Europe After the Rain, and Gorecki’s Symphony No. 3 to reveal the political value of more poetic interventions and creative responses to conditions we elect to term “the intolerable.” Indeed, if the reduction of life to some scientific variable, capable of being manipulated and prodded into action as if it were some expendable lab rat, became the hallmark of violence in the name of progress, it was precisely the strategic confluence between the arts and politics that enabled us to challenge the dominant paradigms of twentieth-century thought. Hence, in theory at least, the idea that we needed to connect with the world in a more cultured and meaningful way appeared to be on the side of the practice of freedom and breathed new life into politics.

And yet, despite the horrors of the Century of Violence, our ways of thinking about politics not only have remained tied to the types of scientific reductions that history warns to be integral to the dehumanization of the subject, but such thinking has also made it difficult to define the very conditions that make a new politics possible. At the same time accelerating evolution of digital communications radicalizes the very contours of the human condition such that we are now truly “image conscious,” so too is life increasingly defined and altered by the visual gaze and a screen culture whose omniscient presence offers new spaces for thinking dangerously. This hasn’t led, however, to the harnessing of the power of imagination when dealing with the most pressing political issues. With neoliberal power having entered into the global space of flows while our politics remains wedded to out dated ways of thinking and acting, even the leaders of the strongest nations now preach the inevitability of catastrophe, forcing us to partake in a world they declare to be “insecure by design.”

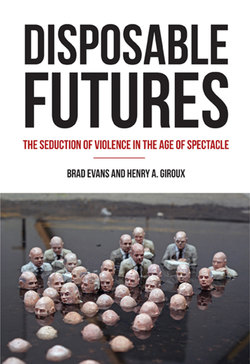

Isaac Cordal’s Follow the Leaders, which appears on the cover of this book, captures this horrifying predicament of our contemporary neoliberal state of decline. While Cordal’s work is commonly interpreted as providing commentary on the failures of our political leaders to prevent climate change, we prefer to connect it more broadly to the normalization of dystopian narratives in a way that forces us to address the fundamental questions of memory, political agency, responsibility, and bearing witness to the coming catastrophes that seemingly offer no possibility for escape. Indeed, while the logics of contemporary violence are undoubtedly different from those witnessed by Levi in the extermination camps of Nazi Germany, Cordal’s work nevertheless points to emergence of a new kind of terror haunting possibilities of a radical democracy, threatening to drown us all beneath the contaminated waters of a system that pays little regard to the human condition. To quote the contemporary artist Gottfried Helnwein:

Mussolini once said: “Fascism should rightly be called Corporatism, as it is the merger of corporate and government power.” Well, look around—does it look like there is a growing influence of bankers and big corporations on our governments and our lives? The new Fascists will not come as grim-looking brutes in daemonic black uniforms and boots, they will wear slick suits and ties, and they will be smiling.1

With this in mind, our decision to write this book was driven by a fundamental need to rethink the concept of the political itself. Just as neoliberalism has made a bonfire of the sovereign principle of the social contract, so too has it exhausted its claims to progress and reduced politics to a blind science in ways that eviscerate those irreducible qualities that distinguish humans from other predatory animals—namely love, cooperation, community, solidarity, creative wonderment, and the drive to imagine and explore more just and egalitarian worlds than the one we have created for ourselves. Neoliberalism is violence against the cultural conditions and civic agency that make democracy possible. Its relentless mechanisms of privatization, commodification, deregulation, and militarization cannot acknowledge or tolerate a formative culture and social order in which non-market values as solidarity, civic education, community building, equality, and justice are prioritized.

This is a problem we unfortunately find evident in dominating strands of leftist thought which continue to try to resurrect the language, dogmatism, and scientific idealism of yesteryear. Rather than being mined for its insights and lessons for the present, history has become frozen for too many on the left for whom crippling orthodoxies and time-capsuled ideologies serve to disable rather than enable both the radical imagination and an emancipatory politics. There can be no twentieth-century solutions to twenty-first-century problems, what is needed is a new radical imagination that is able to mobilize alternative forms of social agency. It is therefore hoped that the book will both serve as a warning against the already present production of our disposable futures, and provide a modest contribution to the much needed conversation for more radically poetic and politically liberating alternatives.