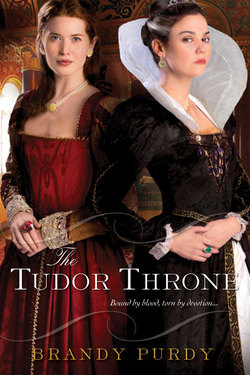

Читать книгу The Tudor Throne - Brandy Purdy - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE

The End of an Era

January 28, 1547

Whitehall Palace

Wonderful, dangerous, cruel, and wise, after thirty-eight years of ruling England, King Henry VIII lay dying. It was the end of an era. Many of his subjects had known no other king and feared the uncertainty that lay ahead when his nine-year-old son inherited the throne.

A cantankerous mountain of rotting flesh, already stinking of the grave, and looking far older than his fifty-five years, it was hard to believe the portrait on the wall, always praised as one of Master Holbein’s finest and a magnificent, vivid and vibrant likeness, that this reeking wreck had once been the handsomest prince in Christendom, standing with hands on hips and legs apart as if he meant to straddle the world.

The great gold-embroidered bed, reinforced to support his weight, creaked like a ship being tossed on angry waves, as if the royal bed itself would also protest the coming of Death and God’s divine judgment.

The faded blue eyes started in a panic from amidst the fat pink folds of bloodshot flesh. As his head tossed upon the embroidered silken pillows a stream of muted, incoherent gibberish flowed along with a silvery ribbon of drool into his ginger-white beard, and a shaking hand rose and made a feeble attempt to point, jabbing adamantly, insistently, here and there at the empty spaces around the carved and gilded posts, as thick and sturdy as sentries standing at attention, supporting the gold-fringed crimson canopy.

There was a rustle of clothing and muted whispers as those who watched discreetly from the shadows—the courtiers, servants, statesmen, and clergy—shook their heads and shrugged their shoulders, knowing they could do nothing but watch and wonder if it were angels or demons that tormented their dying sovereign.

The Grim Reaper’s approach had rendered Henry mute, so he could tell no one about the phantoms that clustered around his bed, which only he, on the threshold of death, could see.

Six wronged women, four dead and two living: a saintly Spaniard, a dark-eyed witch—or “bitch” as some would think it more apt to call her—a shy plain Jane, a plump rosy-cheeked German hausfrau absently munching marzipan, and a wanton jade-eyed auburn-haired nymph seeping sex from every pore. And, kneeling at the foot of the massive bed, in an attitude of prayer, the current queen, Katherine Parr, kind, capable Kate who always made everything all right, murmuring soothing words and reaching out a ruby-ringed white hand, like a snowy angel’s wing, to rub his ruined rotting legs, scarred by leeches and lancets, and putrid with a seeping stink that stained the bandages and bedclothes an ugly urine-yellow.

Against the far wall, opposite the bed, on a velvet-padded bench positioned beneath Holbein’s robust life-sized portrait of the pompous golden monarch in his prime and glory, sat the lion’s cubs, his living legacy, the heirs he would leave behind; all motherless, and soon to be fatherless, orphans fated to be caught up in the storm that was certain to rage around the throne when the magnificent Henry Tudor breathed his last. Although he had taken steps to protect them by reinstating his disgraced and bastardized daughters in the succession and appointing coolly efficient Edward Seymour to head a Regency Council comprised of sixteen men who would govern during the boy-king’s minority, Henry was shrewd enough to know that that would not stop those about them from forming factions and fighting, jockeying for position and power, for he who is puppetmaster to a prince also holds the reins of power.

There was the good sheep: meek and mild, already graying, old maid Mary, a disapproving, thin-lipped pious prude, already a year past thirty, the only surviving child of Katherine of Aragon, the golden-haired Spanish girl who was supposed to be as fertile as the pomegranate she took as her personal emblem.

The black sheep: thirteen-year-old flame-haired Elizabeth, the dark enchantress Anne Boleyn’s daughter, whose dark eyes, just like her mother’s, flashed like black diamonds, brilliant, canny, and hard, as fast and furious as lightning; a clever minx this princess who should have been a prince. Oh what a waste! It was enough to make Henry weep, and tears of a disappointment that had never truly healed trickled down his cheeks. Oh what a king Elizabeth would have been! But no petticoat, no queen, could ever hold England and steer the ship of state with the firm hand and conviction, the will, strength, might, and robust majesty of a king. Politics, statecraft, and warfare were a man’s domain. Women were too delicate and weak, too feeble and fragile of body and spirit, to bear the weight of a crown; queens were meant to be ornaments to decorate their husband’s court and bear sons to ensure the succession so the chain of English kings remained unbroken and the crown did not become a token to be won in a civil war that turned the nation into one big bloody battlefield as feuding factions risked all to win the glittering prize.

“Oh, Bess, you should have been a boy! What a waste!” Henry tossed his head and wept, though none could decipher his garbled words or divine the source of his distress. “Why, God, why? She would have held England like a lover gripped hard between her thighs and never let go! Of the three of them, she’s the only one who could!”

And last, but certainly not least—in fact, the most important of all—the frightened sheep, the little lost sheep, the weak and bland little runt of the flock: nine-year-old Edward. So soon to be the sixth king to bear that name, he would be caught at the center of the brewing storm until he reached an age to take the scepter in hand and wield power himself. He sat there now with his eyes downcast, the once snow-fair hair he had inherited from the King’s beloved “Gentle Jane” darkening to a ruddy brown more like that of his uncles, the battling Seymour brothers—fish-frigid but oh so clever Edward and jolly, good-time Tom—than the flaxen locks of his pallid mother or the fiery Tudor-red tresses of his famous sire. His fingers absently shredded the curly white plume that adorned his round black velvet cap, letting the pieces waft like snowflakes onto the exotic whirls and swirls of the luxurious carpet from faraway Turkey. He then abandoned the denuded shaft to pluck the luminous, shimmering Orient pearls from the brim, letting them fall as carelessly as if they were nothing more than pebbles to be picked up, pocketed, and no doubt sold by the servants. Like casting pearls before swine!

“Oh, Edward!” Henry wept and raged against the Fates. “The son I always wanted but not the king England needs!”

Katherine Parr rose from where she knelt at the foot of the bed and took a jewel-encrusted goblet from the table nearby and filled it from a pitcher of cold water. Gently cupping the back of her husband’s balding head, as if he were an infant grown to gigantic proportions, and lifting it from the pillows, she held the cup to his lips, thinking to cool his fever and thus remedy his distress. But not all the cool, sweet waters in the world could soothe Henry Tudor’s troubled spirit.

The black-velvet-clad sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, the rich silver and golden threads on their black damask kirtles and under-sleeves glimmering in the candlelight like metallic fish darting through muddy water, sat on either side of their little brother, leaning in protectively. But as they comforted him with kind, reassuring words and loving arms about his frail shoulders—the left a tad higher than the right due to the clumsy, frantic fingers of a nervous midwife and the difficulty of wresting him from his mother’s womb—their minds were far away, roving in the tumultuous past, turning the gilt-bordered, blood-spattered, angst-filled pages of the book of memory. . . .