Читать книгу National Geographic Kids Chapters: White Water - Brenna Maloney - Страница 7

Оглавление

Credit 2

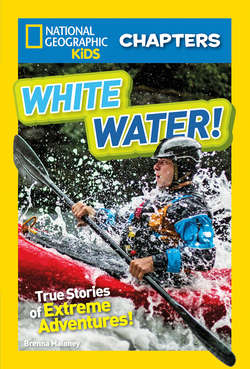

The team rests in a patch of cottongrass after scouting the first portion of the Headwaters Canyon.

Alaska, U.S.A.

Todd Wells was wide-awake. Around him, his teammates snored and mumbled in their sleep. But not Todd. As expedition leader, he had too much on his mind. He had led other expeditions before, but none like this one. Todd and his five teammates were about to try something that no one had ever done before. And it was risky.

Todd’s group was camped in the heart of the Wrangell (sounds like RANG-guhl) Mountains. Their tents were nestled in one of Alaska’s most breathtaking valleys. But they weren’t here to camp. They were here to run the Chitina (CHIT-nuh) River.

“Running” the river means traveling down it in kayaks (sounds like KY-yaks). All six team members were experienced kayakers. Yet this 130-mile (209-km)-long river is unique.

Lower parts of the Chitina River are a favorite among boaters, who take to the river in kayaks, rafts, canoes, and other small boats. But one section of the river had never been run. That’s because until recently, this section was covered in ice.

The source of the river—called the headwaters—comes from the towering Logan Glacier (sounds like GLAY-shur). This massive block of ice flows into the river from the east. The Chugach (sounds like CHOO-gach) Mountains lie to the south. The Wrangells are to the north. A deep canyon cuts between these ranges, and the Chitina runs through the canyon. The first 10 miles (16 km) of the river have always been frozen and impassable.

Over time, changes in the climate have brought about warmer temperatures. The Logan Glacier has been slowly but steadily melting. As a result, this ice has become turbulent (sounds like TUR-byuh-lent), fast-moving water. Is it passable? That’s what Todd and his team had come to discover.

For more than a year, the team had been planning this expedition. They had pored over topographic (sounds like top-uh-GRAF-ik) maps and satellite (sounds like SAT-uh-lite) images of the river. They had talked to local people who had grown up in the area and knew the river well. They talked to other kayakers and boaters who had paddled the lower sections of the river. They had done their homework. But now that they were here, Todd knew he needed to read the river with his own eyes. The best way to do that was from the sky.

After his restless night, Todd asked a local bush pilot to take him up in his small plane. The plane lifted off from a runway in McCarthy, an end-of-the-road town in the Wrangell–St. Elias National Park.

It easily carried them above the Logan Glacier and over the Headwaters Canyon. For the first time, Todd could see clearly what they had been studying. But he wasn’t ready for what he saw.

Credit 3

It wasn’t like looking at a map or a photo. This river moved. A lot. The gray, murky water churned. To Todd, it seemed like a living, breathing beast.

The scale of the river overwhelmed him. It was massive. In the photos, some features had looked small and easy. In real life, they were very different. He saw waves towering 10 feet (3 m) high or taller. There were deadly pour-overs, where shallow water moved quickly over partially submerged (sounds like suhb-MURJD) rocks. From upstream, these looked like big, rounded waves. But Todd knew that once a paddler got over one, he could get caught in the swirling water.

The pilot flew over the river several times so that Todd could make sense of what he was seeing. The sheer volume of water worried Todd. It was early August and unusually hot. All that heat was causing more glacier melt, which was raising the levels of the river. Too much melt, Todd thought. The conditions aren’t good. They aren’t safe.

The pilot flew on. There was a specific point in the river he wanted Todd to see. It was a rapid they called “the Pinch.”

Credit 4

Glaciers are huge masses of ice that “flow” like very slow rivers. They form over hundreds of years where fallen snow compresses (sounds like kuhm-PRESS-ez) and turns into ice. Glaciers form the largest reservoir (sounds like REZ-er-vwahr) of freshwater on the planet. In fact, they store 75 percent of the world’s freshwater! Warmer weather has led to faster melting of the Logan Glacier. In the past 40 years, it has shrunk by 40 percent.

Did You Know?

A rapid is a place in a river where water flows faster and turns white and frothy.

The Pinch came at the end of a 10-mile (16-km) stretch of the river. It was the biggest challenge they would face. Here, the river narrowed, and the water squeezed through a gap in the canyon walls. Todd knew there were some large, jagged rocks at the mouth of the Pinch, but from the air he couldn’t see them. The water levels were so high, and the water was moving so forcefully, that the rocks were hidden. If the kayakers couldn’t see the rocks, they would not be able to steer clear of them.

Todd had a difficult decision to make. Were the timing and conditions right for this expedition? That evening, he and the team held a meeting. Together, they decided that the risks were too great. They would have to postpone the trip until the weather cooled and the water levels dropped.

During the wait, Todd had another problem to solve. How would the team get their kayaks to the river? They couldn’t carry them. The distance was too far and the location too remote. He could think of only one way—by air.

Finally the time came. Each 9-foot (3-m)-long, 50-pound (23-kg) kayak was strapped to the bottom of the plane and flown, one by one, to the starting point.

Todd was eager to see the river again, so he went first. When he and the pilot flew over the Pinch, Todd’s stomach tightened. The water levels had not dropped. The river raged as it had before.