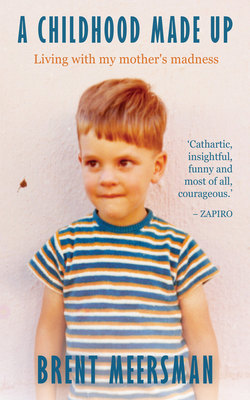

Читать книгу A Childhood Made Up - Brent Meersman - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

One

ОглавлениеSIGNS IN THE STUDIO

I REMEMBER SLEEPWALKING when I was a small boy. I was outside in the silent, dead hours, walking along the landings of the block of flats where I grew up, my body taken over by the impulse of a dream; not asleep but not awake either.

I was in my flannel pyjamas, something I would one day give up when I decided I was a grown man and allowed to sleep naked if I chose, only years later to go back to flannel pyjamas, wearing them when I wanted to let the memories come flooding back. I remember well those pyjamas with their paisley pattern, whorls within whorls, trees full of teardrops not dew.

Where was I going? Why was I out of bed?

I am back there now. My toes are ice-cold. My forearms and calves are bare for I have long since outgrown my pyjamas. I am not sure if my eyes are open, yet I can see where I’m going, as if looking through a waterfall. My arms are not stretched out in front of me, as an actress might do in the Scottish play, but hang naturally at my sides. My small, bare feet hardly make a sound on the concrete, which is so smooth it becomes lethal in the rain. My mother has slipped and fallen more than once here. I stub my big toe on a join in the concrete but feel no pain.

I climb the stairs to the second floor, then the third. I walk on the landing to the far staircase, then descend to the ground floor and return home having completed a great rectangular journey that took me three storeys up in the sky.

‘We found you at the front door last night,’ my mother tells me the next morning. ‘I heard a sound, someone fiddling with the door handle. I thought a burglar was trying to pick the lock! But I saw a small shadow through the glass; I recognised you at once.’

I don’t look up. Instead I dip my spoon into the bowl of porridge, quickly, before it forms that revolting skin.

‘… I can recognise you anywhere, my darling, even the faintest glimpse of your silhouette and I know it’s you … ’ Her gaze is inescapable.

I did clearly remember being outside that night, but I acted surprised and didn’t say anything. The rest of my somnambulistic meanderings were there but cloudy, yet I had no recollection at all of what she told me next. Like most dreams it had vanished upon waking. What happens to all those dreams we forget? Where do they go? Do dreams not form memories? Or do they wait for us, committed to some dark recess of our minds, like memories we suddenly recall?

‘I opened the door and you were standing there in a daze. I said very softly to you, “Come to bed, sweetheart.”’

I must have locked myself out; I could hardly have planned ahead for when my mind chose to set off with my body on one of its night-time adventures.

‘… I just took you gently by the hand and led you back to bed. You really were fast asleep on your feet … You do know that you must never wake someone in the middle of sleepwalking?’ She said it as if I were likely to bump into sleepwalkers on a regular basis. ‘The shock can be so terrible they never recover their minds. They can have a heart attack.’

A shiver goes through me. I glance down. I hate dirty feet and my soles are pitch black. There is the proof from being out on the landings. I want to bathe at once.

My parents caught me several times in the middle of the night fiddling with the latch and chain on my way out the front door. They also told me that I spoke in my sleep, fairly loudly, even shouting. I was afraid of what I might have said, that I might have betrayed my inner world.

‘Oh, what was I saying?’ I would ask, trying not to sound too alarmed, and I’d yawn for effect.

‘Nothing we could make out, just gibberish. Do you remember anything, dovey? Anything at all?’

I gave a little shrug. I have no idea why I didn’t want to admit to my mother that I did in fact remember walking on the landings at night. Perhaps I was afraid that if I admitted this, then she’d think I had only pretended to be asleep, in which case I had been misbehaving, wandering about alone at night, barefoot, catching cold. But if you didn’t know what you were doing because you were asleep, were you still being naughty?

Yet in my mother’s voice I sensed a deeper concern. Because I talked in my sleep and went sleepwalking and often had nightmares, did she think there was something wrong with me – the way she worried about herself?

A theory has it that one of the functions of sleep is to make emotional sense of traumatic events in our lives and neutralise them. When this fails, you are doomed to have repeated nightmares. I had night terrors and thrashed about suffocating in my sheets right into adulthood. I kicked in my sleep and could be quite dangerous to be near. I knew when I had had these night terrors – when I woke up in the morning and even my stubbornly affectionate cat had fled to the couch in another room.

But when I was sleepwalking as a child, I felt completely safe. I had no fear of the dark; no fear of the unknown; no fear of the world out there. When I was awake, I was afraid of almost everything.

I am told that sleepwalking is a sign of sleep deprivation; your body has such a deep desire for sleep that it keeps your mind in dream mode even though it has released your limbs. What kept me awake at night as a child? And why did I go outside? Was I running away or was I looking for something?

Why do we dream at all? Or perhaps, the bigger question is: why must we wake up?

I wondered what my father thought of all this, but by the time my mother woke me in the morning, he’d already be at work, having left as usual with his sandwich box and thermos flask long before the rest of the family rose. My brother was already at school. It was just me and my mom in the kitchen; me and my mom alone, the way it often would be over the years.

My mother had long auburn hair in those days, which reached down to her shoulder blades, hair full of life that bounced when she walked. She was a trim woman with an angular, slightly boyish body. She dressed in slacks, never dresses; a real bluestocking, she said of herself proudly. She smelled of English Lavender, the talcum powder she used to soften her skin, and a faint aroma of fresh, soft, green moss, and of camphor, and the fragrant sharpness of pine needles. Her arms were covered in freckles; sun damage from when she was a girl growing up on a farm on the edge of the Kalahari desert. Her name was Shirley. She was born in 1925 in Vryburg.

Mommy had two round patches on her right breast, like bullet holes, but white like the flesh inside a coconut, so smooth the skin seemed brand new. When I asked her why her skin was so different there, she said they were scars from an operation. She often complained her breasts were sore and I wasn’t allowed to rest my head on them, ever. Her tummy was also sensitive, and I had to be careful if I played on top of her.

Her face wasn’t yet as harrowed as WH Auden’s (it would be when she reached her sixties), but there were plenty of creases already, because her face was always busy with her feelings, and she chain smoked. She had deep frown lines, not from frowning so much as from lifting her eyebrows when she spoke.

Mommy could only raise hers together. I trained myself in front of the mirror to lift one brow at a time – left, right, left, right. I wanted to see how high I could make my eyebrow go without moving another muscle on my face. The shape my single raised eyebrow made at its highest elevation was like the invention of a new musical note. I tried to imagine what sound it stood for; a sort of crystal ping came to mind.

My face didn’t have the faintest line or blemish then, but I could see blue veins running under my skin, which was sickly white because I almost never went outside to play. If I raised one eyebrow while pulling the other one down, I got a crease above the nose and a comical expression. Then I started on my ears. That was more difficult, especially if I wanted to keep my mouth straight. But I got it right, eventually, juggling my ears individually. I could amuse myself for quite some time isolating bits of my face. Flaring my nostrils was easy, but how many people could also make the tip of their nose waggle left, then right? I could make my upper cheek shudder and my eyelid twitch out of control as if I were having some kind of fit.

Where did I get such an idea? Or was it just a child’s irresistible compulsion to pull all kinds of faces, to make itself ugly-faced, to discover what can be said or hidden with purely a look, like the silent violence of a smile withdrawn.

Soon I was ready to impress my mother with my new talents. I wiggled my eyebrows and my ears as fast as I could. Ping, ping, ping. Mommy laughed, but in a dismissive way. ‘Don’t do that. You look daft,’ she said, and the corners of her mouth turned down.

I thought maybe I should pull out all the stops and do my lying-on-the-floor-having-a-fit routine, with my arms and legs flailing about. But something told me she wouldn’t like that either. I might have done something like that once before and she had shouted at me.

‘Children can be awfully cruel, making fun of people,’ she said. I didn’t understand. I didn’t see the connection.

She said the boy who lived in the flat next door was just such a perfect example of the cruelty of children; naughty and thoughtless, which amounted to the same thing. She had nicknamed him Turtle because he was chubby and round and had stumpy limbs. She loathed him. ‘Horrible, horrible child,’ she’d say. But I mustn’t hate Turtle, mustn’t hate anyone ever, she said. I should even be kind to critics and art dealers. But she had to admit, she simply couldn’t abide the sight of that little blighter. Turtle had done something unforgivable.

In our block, adjacent flats on the ground floor shared a rectangle of garden between their balconies. A chameleon had been living in ours for over a year. One day Turtle stamped it to death and destroyed most of our garden. ‘Just for the fun of it!’ my mom cried. A chameleon! Was there any creature more harmless in this whole world? Her hands were shaking. My father’s hands shook too, but that was for a different reason.

I used to watch that exotic being, with its swivelling, cone-shaped eyes, for what seemed like hours. It was bright yellow and radiant green with flesh-pink patches on its sides. My dream was to witness it one day catching a fly or a cricket, but before the chameleon could perform the marvel of its weaponised tongue for me, Turtle had pulverised it to death.

How could Turtle have not seen its reptile beauty? It had been living silently in the tiny garden all this time, mostly unnoticed, minding its own business. Somehow, this solitary, prehistoric-looking creature had even managed to evade our cat. I knew how unique chameleons were; my mom said they could change colour to camouflage themselves. I wondered if there were people who could change colour too.

Once, I tried picking it up, prising its sticky toes from its branch. I must have squeezed and hurt it, for its mouth opened wide, big enough to swallow half its own body, and it let out a scream. Apparently, chameleons don’t scream so maybe it hissed. But that is not what I heard; I heard a penetrating, almost human scream. I dropped it back on its tree and ran, heart pounding.

I prayed the chameleon was all right. I feared I’d damaged its organs. I could still feel the scaly sack of its bulging body through my fingertips.

But then along came Turtle. He was no different from other boys, said Mom. Most boys liked to go out and kill things just for the thrill of it – crunching snails under their shoes, chopping earthworms in half and watching them wriggle, shooting doves with pellet guns. And doves are the symbol of peace, she said. Picasso had drawn one for the United Nations, where my exotic Aunt Sonya, my mom’s youngest sister, worked.

Mom said Turtle’s parents should have taught him better. Turtle was a normal kid; that is to say he was a proto-psychopath, which is a person without feelings for others. In time, most parents manage to sensitise and civilise their offspring. It was I who was different; I was not like the herd, like other kids; I was like her – born sensitive! The world was not kind to people of our nature, she said, ‘but may you always stay that way, my darling, for the meek will inherit the earth’.

I nodded, but something told me it wasn’t possible. At some point I’d have to defend myself, and there would be times when I would have to stop myself feeling. Already, my feelings were unbearable.

‘It’s because children are brought up in cities and buildings,’ my mom explained. ‘They are cut off from nature. Children should be raised with animals. Kids in big cities, like New York and Tokyo, they think milk comes in bottles! They don’t even know what a cow is. They think milk is made in a factory.’

She drew a picture of a cow to explain. I preferred the idea of milk coming out of factory bottles, not being squirted out of dangly cow tits.

Then she drew an exquisite illustration of my favourite nursery rhyme. For many years, when I was miserable, I’d recite it:

Hey, diddle, diddle,

The cat and the fiddle,

The cow jumped over the moon;

The little dog laughed,

To see such sport,

And the dish ran away with the spoon.

Over and over again like a mantra, that last bit – ‘the dish ran away with the spoon’ – especially comforted me. I could easily imagine a cat playing a fiddle with such gusto that even a cow could hurdle the moon, and a dish and a spoon elope to a better world where they wouldn’t be used by people.

My mom would spend hours on end painting in her studio. The walls of our flat were already covered in her oil paintings, with their beautiful, strong colours. There were jungles and deserts and oceans for me to gaze into and dozens of strange men and women gazing back at me – a blue man with a fez, who she said was a merchant from Isfahan; a Chinese lady in orange with a pigtail who had come fully sprung from my mom’s imagination; a many-headed green monster which she said was there to frighten nightmares away; and a naked Greek hero, with his arms outstretched like Jesus on the cross, plunging from the sky. The wax that had held his golden wings together had melted because he’d flown too close to the sun, she said.

We had a handful of works by other artists. In Mom’s bedroom was a small Irma Stern watercolour of the flower sellers in Adderley Street, which the famous artist had given her as a gift. I thought it fairly unimaginative and trite when set alongside my mother’s work, but my mom loved it and I remember her repeatedly saying as she stared at it, ‘If only I could paint that well … If only.’

Mostly my mom did works in pen and ink and watercolour. She filled a whole book in a week. Occasionally, she would draw in pastels and Conté crayon on large sheets of paper that were so expensive they made her nervous. Only when she could muster enough energy did she paint in oils, a medium as time-consuming, tricky and demanding as it is rewarding.

She quoted Leonardo da Vinci: ‘An artist’s strength lies in solitude.’ Yet as children we were not banished from her studio, although there wasn’t much room in that poky work space for me and my brother.

It is only recently that I had the startling realisation that up to the age of six I had absolutely no playmates my own age. This only changed when I went to primary school and at first I was terrified of the other kids. Even later, I would have very limited interaction with my school friends outside school hours.

Meanwhile, my brother, Paul-Henri, named after our father, William Paul, and our grandfather, Henri François, was already out in the world being three years older than me. He would return home with grass stains on his knees and bruises on his arms and legs, evidence that the world outside was a dangerous place. We would watch with fascination over the course of several days as his bruises changed colour – pink, ghastly blue, deep purple, mustard, occasionally bilious green. He called them medallions. He seemed to get into a lot of fights. I think he was much bullied, but he appeared undeterred.

I, on the other hand, stayed home, almost never leaving the flat in our three-storey block, which was not quite high enough to jump off by the time you were an adult. The flat was in Milnerton, Cape Town, on the ‘right’ side of the railway lines, so to speak, not on the tracks but close, on the border of Rugby, the suburb where my mom said the ‘low-class types’ lived. As a child, I sometimes wondered about living in a house over there with the common people, rather than in our childless flats where the only other children were two little thugs who lurked upstairs and the horrid Turtle next door. Some nightmarish families, always fighting, came and went over the years, but most people in our block were retired or close to it, while across the railway line there were big, noisy families with lots of children and plenty of pets. But my mom said I mustn’t go near them.

Mom said teenagers were especially to be avoided. She said three teenagers had been put on trial for murdering a toddler. They’d pushed him into a sewer drain for a bit of fun, then stamped on his fingers until he fell. When asked by the judge why they did it, one of them said he had merely wanted to experience what it felt like to kill another person.

On my way to school my heart would quicken, and I’d almost break into a run when I had to pass the storm drains on the curb. I was terrified a gang of teenagers would suddenly appear, even though I couldn’t see how they could possibly fit my body down the maw of that drain.

While my mother was absorbed in painting, I calmed myself by drawing. Much as I loved being near her in the studio with its warm smell of oil paint and the cool evaporation of turpentine, I would go off to the lounge and spread myself on the carpet with a big sheet of paper and a world atlas. I liked copying maps, memorising the outlines of the continents and even the internal borders of some countries. The most difficult thing was choosing where to begin the outline so it would all fit on the paper. I usually started with Africa as it was smack bang in the centre of the world, and I loved its simple shape. I did not use tracing paper and it took me some time to master copying to scale by freehand. I am still able to sit down and draw a vaguely accurate world map purely from memory. Back then, I never dreamed that by the time I turned fifty, I would have visited more than half the countries on the coastlines of the world, including the Antarctic. Such voyages were far beyond the realm of possibility in that cramped, working-class flat beside the railway line.

I took a while to figure out map scales, eventually leading me to one of my first insights about depicting the world. I had always tried to copy the atlas as closely as possible, the intricate detail of the little inlets, the fjords, river mouths and gulfs that make up a coast – the south of Chile and the north of Norway being the most demanding. But I soon discovered that everything changed depending on the map I was copying. The smaller the scale, the more ragged and intricate the shapes would become; as the scale increased, detail disappeared.

One afternoon standing at the lagoon mouth in Milnerton, I realised that even if I were to plot a life-size map, on a scale of one to one, I would still have to make a choice. If I chose the point at which the water touched the land to be the coastline, it was only accurate for a moment, for embankments slanted into the water, and depending on the height of the tide the coastline shifted – in some places on earth it could shift by miles within a day. One would have thought no drawing could be more accurate than a map, but I had discovered that even mapmakers made choices.

The world changes too; coastlines crumble into the sea or rise with earthquakes and volcanic flows; continents drift and the march of human history shifts borders. Our family atlas was out of date and still tinted half the world with British pink. Some countries, like Nyasaland and Bechuanaland next door, had already disappeared, so my father informed me, tapping the map where I had drawn a country that no longer existed. Back then of course I had no idea what that had meant for the people who lived there. I was just frustrated. Why was our atlas wrong, so out of date?

I think it is unusual for a young child to concentrate so single-mindedly on such a task for so many hours on end. It would stand me in good stead later in life when I went to university, the first generation of my family to do so. But maybe I was simply copying my mother, for she would sit tirelessly at her desk or stand working at her easel for most of the day. Whether she was finding herself or losing herself in her art, I cannot say. No one could have known at the time that those would be her most productive years as an artist, and I could not have known then that it would be many years before my life would be as safe and as well arranged again.

It sounds fancy having a studio, but it was merely the third bedroom of a hundred-square-metre flat, and it was the reason I had to share a room with my brother. Mom’s work desk was rudimentary. To achieve the slanted drawing surface that she needed, a large piece of hardboard had been propped up at its top end with bricks. An old boyfriend of my exotic UN aunt, who was a draftsman, had given my mom an adjustable architect’s table lamp so she could have strong light to paint. To me the lamp was a terrifying contraption; its unpredictable springs would suddenly send it catapulting out of control, smashing the bulb. It was like many things in our home: unpredictable because they were broken.

When I was exhausted of drawing maps, I would go to the studio to show my mother. But she was often far away, blankly staring into space, I thought fixated on her own creations. I knew watercolours could not be easily interrupted; she had to paint before the paper dried. I knew art required a lot of concentration and the slightest interruption of the process could set the creator back hours. She said she couldn’t work like Picasso. He did most of his painting in the solitude of night, but during the day he had dogs and children chasing each other all around his easel. No, I had to wait for the right moment, which came when she put down her brush and looked about her, slightly surprised.

Once, when I was a toddler, she was jolted out of painting by a gulping sound behind her. In the precarious grip of my two little hands was the jar she used for rinsing her watercolour brushes, and I was quaffing the murky water down.

‘Some paints are highly toxic. I didn’t know what the effect would be,’ she told me when I was five. ‘I watched you closely for hours after that. The water was blue. Maybe you thought it was a cooldrink.’

Or maybe she just hadn’t noticed I was dying of thirst. We laughed about it. I wondered if the colour of my insides had changed. I imagined they now resembled a stormy sea. It is one of my earliest memories.

I have other memories of being an infant and I doubt these were implanted, as my mother had no recollection of them and she couldn’t have told me about them, nor could she even confirm these memories later, because, as you will see, she was forced to forget so much.

I remember I would go to the fridge, take out the milk and stand there. I would wait, holding that cold neck of the bottle, with a patience far beyond my years. My mind was busy imagining all sorts of things and time could pass happily. Eventually, my parents would realise I had disappeared. ‘Where’s Brent?’ I’d hear one of them ask. They soon learned to rush to the kitchen. I would be waiting beside the open fridge door. Some of my milk teeth were missing, making the impish grin on my face look cuter but naughtier. They’d say, ‘Put it down’ or ‘Put it back’ or ‘Brent, give it to Mommy’. But the minute one of them took one step closer, I handed the bottle over to gravity. My parents never learned. It was a game I played for some time.

Children crave attention, but dropping milk bottles?

My mother called it her absentmindedness. She said it ran deep on the Morris side of her family. If she didn’t put things in a dedicated pocket or a specific place, she’d end up spending half her life looking for such nuisances as keys. She had a series of handbags for different purposes: for going to the local shop, for going with my second aunt to the city, and for going to the hospital. Then there were other handbags that never seemed to go anywhere.

Yet things still went astray. Her reading spectacles had a truant life of their own. Once they went missing for two days and she had no choice but to go shopping in town with my aunt without them. She thought maybe it was time to get her eyes tested anyway and to buy a new pair, if she could afford it. But when she went to pay her account at Garlicks department store, where she bought little luxuries she had saved up for, she opened her handbag only to find deep in its intestines a block of smelly, melting cheddar cheese. Now she knew where her glasses were. But the mystery wasn’t entirely solved, for her spectacles were at the far back of the fridge, almost iced up, where the cheese was never kept. Sherlock Holmes would not have been satisfied. Later, other things would be found in the fridge that didn’t belong there, unless you believed otherwise.

Family lore was full of such stories, and when they were related by my father to third parties, the expression on my mother’s face was not one of simple embarrassment.

My father enjoyed recounting another example of my mother’s absentmindedness, the occasion when she salted some frozen peas and couldn’t understand why they kept foaming up in the pot as they boiled. She dished them up none the less. ‘Very strange peas,’ she told everyone as we sat down to mush them. The mistake was discovered at the first bite. She had used a cleaning powder called Vim, which came in a tall white plastic container vaguely resembling that of Cerebos salt.

She’d blush slightly when my father would finish telling such stories, and then she would smile as if to laugh it off – the cheese, the Vim – saying, ‘Oh, we all do silly things.’ But I could see sharing such episodes about her was far from innocent; my father was taunting her, and my mother feared for her mind.

Occasionally, my second aunt or her husband would telephone, saying my mom had called while they were out and left a message with their housekeeper to phone back. But Mom couldn’t remember calling them at all. Then she’d wonder who had phoned them and pretended to be her; honestly, the idiotic jokes people got up to!

One way of conquering her absentmindedness was to make signs. There were handwritten signs all over the flat, some old and stained, to remember this and remember that: ‘CLOSE FRIDGE DOOR’; ‘TAKE KEYS’; ‘FETCH WASHING’; ‘PUT OUT MILK BOTTLES’; ‘TAKE TABLETS!!’

When she was in artistic mode little else mattered and the collateral wreckage of being a living organism – breathing, eating and shitting – paled into insignificance. She hated housework, the unpaid labour women are expected to do without even a thank you, an unjust, patriarchal plot to keep her from her art. She drew herself as the Hindu goddess Chandi with eighteen arms, in each hand a form of drudgery: a pot, a broom, a mop, a dustbin lid, a scrubbing brush, a vacuum cleaner pipe, a ball of knitting wool.

Lettie, our domestic worker, was her saviour, though only one day a week; one woman sacrificing her own children and home for another woman trying not to sacrifice her talent to domestic servitude.

Poor whites could afford domestic workers in those days, still can. There was Lettie, then Margaret, then Martha, surnames unknown. My mother painted an affectionate oil portrait of Margaret, which for some reason Margaret didn’t want to take home with her.

Sometimes my mother forgot the time and there would be a mild panic to get supper ready before my father came back from work. He was starving and exhausted by the time he got home, often late. He was trying to get as much overtime as possible, the only way he could earn enough to make ends meet. Unemployment is one thing, but to work nine to eleven hours a day, six days a week, and still not be able to provide for your family is in some respects worse. I remember how he came home after nine p.m. and was gone by six a.m. for weeks on end.

I helped Mom prepare supper. We peeled potatoes. The deep lines on her palms were permanently stained brown by the juice of those tubers. I did my best, but my little hands couldn’t keep pace with hers. Our dinner ration was two spuds per person per day and three for Papa. ‘Drudgery, absolute drudgery,’ my mother lamented as we peeled.

My mom didn’t do homeyness or bake cakes or cook special dinners for hubby. Meals were a perfunctory affair with almost the same seven-day schedule every week: grilled chops, red cabbage and boiled potatoes; chicken pieces and boiled potatoes; frozen hake, green beans and boiled potatoes; celery and tomato stew and boiled potatoes; mince curry and boiled potatoes; fried eggs or pork bangers and spinach mashed with boiled potatoes; tinned pilchards and … rice. But at that stage, there was food on the table every night, something I would later not take for granted.

My father would on occasion cook a special meal on weekends. He concocted stews of steak and kidney with chips made in a deep fryer he’d specially brought with him from Belgium. But for my mother, cooking was a daily bore; for her, life was this constant juggling of household chores competing with her creative dreams.

This was why there were so few women artists, she maintained, and what was more, there wouldn’t have been that many successful male artists either if it hadn’t been for the women in their lives behaving like servants. And many artists, like Renoir, for example, wouldn’t have had anything to paint in the first place if there weren’t beautiful women to inspire them. And Mrs Tolstoy wrote out War and Peace by hand seven times for her husband to get the manuscript in publishable form, she said.

In an ideal world, Shirley would have painted day and night as she chose, without regard to the conventions of three meals a day and the spinning of the earth with its sunrises and sunsets. But despite the household chores and looking after us kids, she was prolific for a number of years.

She liked drawing men. Her men’s bodies were lithe and muscular, always sensual and slightly romanticised, while her women were more realistic and more diverse. Paintings of nudes were all over the house, causing white South Africans in the 1970s and 80s to stare uncomfortably at the carpet if they came inside for any reason. The carpet was old and worn and the thing that was truly embarrassing as far as my mother was concerned. But it was the nudes the South Africans would snigger at, not the carpet.

‘They have such tiny, dirty minds,’ Mom told us. ‘They don’t understand anything beautiful.’ Which was why, I supposed, we had so few guests.

The few visitors who did manage to get inside the flat, also occasionally workmen such as house painters or the plumber, were agog at the nipples and blushed at the penises. A police constable once slurped a mug of hot chocolate in the lounge, not knowing where to look. He turned beetroot. All that crime and violence hadn’t prepared him for a painting showing a modest Athenian genital. The caretaker of the flats cackled at a work called Drink and Dagga. ‘Look, that bloke’s glasses are falling off,’ he observed. Mom laughed when he had left. ‘He doesn’t understand cubism. They just haven’t got a clue, have they? They are like cats or dogs looking at a film screen.’

At first, my mother had hidden the nudes in her studio, but my brother and I kept dragging them out. I wonder why we were so insistent? Was it that we wanted to support our mother and say she had nothing to be ashamed of? Were we thumbing our noses at the neighbours for disapproving of us? Or was it that we were tired of so many things being hidden and unsaid at home?

We won in the end, but my mom did her best to make sure the neighbours didn’t see inside. She had net curtains fitted on all the windows and kept them permanently drawn. Besides the nudes, what might the neighbours have said about the weird and wonderful excrescences of monsters that also adorned our walls?

My mother didn’t care for pretty pictures, although she appreciated the skills of the Impressionists. She loathed what she called ‘picayune Sunday paintings!’ She had a horror of still-lifes, especially Flemish ones, though she said they could paint exquisitely the two most difficult things of all – glass and water. She would also never paint buildings; she thought them boring and architecture the most boring art of all, best left to people who have to use rulers to draw.

She did many paintings of her childhood in Vryburg in the 1920s, of the arid Northern Cape with herds of big horned cattle and wranglers on horses. She told us stories about growing up on the ranch, an idyllic, privileged childhood from the sound of it. Her family had been wealthy once and she was raised without having to do any household chores. These tasks were done by black servants. Tasks like beheading chickens. The man whose job this was, he who wielded the axe, was ‘Old Tom’. When she was a little girl, Tom had taken Shirley aside one day and shown her. She told me how the blood shot out like a fountain and the chicken’s body careered around the yard, headless. ‘It looked like it was running,’ she said, ‘but it wasn’t of course. It was its nerves making the body convulse.’ Little Shirley didn’t want to eat her supper that night, and when she finally confessed why to her parents, it was Old Tom’s turn to get it in the neck.

The family in Vryburg had chambermaids, a cook, and a chauffeur to drive Shirley and her sisters to school, leaving plenty of time to practise piano sonatas and draw pictures. I was not yet old enough to know that nostalgia is a form of wish fulfilment, a longing for a time and a place, a make-believe past, where in truth people were often desperately unhappy, and if those really had been the happiest years of their lives, they certainly wouldn’t have known it at the time.

I loved escaping into my mom’s childhood. Afternoons on the farm were too hot to go out and the sisters would lie on their tummies and sketch or act out stories. At her granny’s homestead someone was always playing Chopin, Liszt or Beethoven, she said. They’d clear the furniture and dance and sing Irish songs. At teatime there were cakes, tarts, scones and cucumber sandwiches. The very young and the very old were all together, four generations of family filling the house. How different life was now, with only she, her husband and her two small children – the nuclear family that has made us all neurotics in the West.

She told me about the day the sky turned black and blotted out the sun, not with clouds but with a mile-long swarm of locusts. Everyone was sent to the fields, frantically beating pans and pot lids ‘like a Chinese opera’. She had always been terrified of those hideous insects with beating wings and spiky legs that kicked. Now there were billions of them landing on every surface and gorging themselves on the fields. The farm workers filled sacks writhing with locusts and ate them.

There were other vast clouds that swept across the land, but of sand – the great dust storms that blew in from the Kalahari desert like something out of the Bible. In the heat there were also whirlwinds. You’d hear a swoosh and then an explosion as the tiny tornado suddenly detonated into existence out of thin air. Then these dust devils would dance across the desert, causing havoc wherever they went, strong enough to knock a young girl off her feet.

Rain clouds seldom materialised. Sometimes white marbled clouds would build in the blue sky for a few hours and tease her father before evaporating into thin air. But when it did rain, the whole world changed. Giant drops drummed onto the parched soil. Horses cantered about skittishly; even the cows would liven up. The rain was frequently torrential, flooding the fields and filling dongas. Roads became impassable. There were flash floods in the ravines, sweeping away whole trees and unsuspecting people who were walking along in what a second before had been a dry river bed. Overnight, green shoots would emerge and the whole world was renewed with the smell of wet earth. Shirley missed the farm, so she painted and drew many pictures of it.

Even shopping – another pastime she hated – was peaceful back in those days, she said. One would chat to the shop assistant, who was not a stranger, and one could do so without someone waiting impatiently behind you for you to finish, curiously peering at what you had bought and silently criticising your choices.

The city was a shock to her at first, and Cape Town in the 1950s was only barely a city. She said the thing that struck her most when she arrived was the number of poor people.

‘Picasso used to go hungry when he first moved to Paris,’ she told us. ‘He had to live on the smell of his oil rags.’ Picasso was her hero because he observed the laws but broke all the rules. His genius gave her the permission she sought: ‘To paint what is in myself, not what is expected of me.’

‘I don’t want to be taught and I don’t want to imitate,’ she explained. ‘I am a savage – raw, genuine, untutored!’

I nodded. Would she now help me tie my shoelaces?

‘Paint anything you like and how you like on anything you like!’ This was a mantra she’d picked up from a Belgian artist and friend of the family, Herman van Nazareth. ‘He burns his paintings if he doesn’t like them,’ Mom said with frightening relish.

When a picture was driving her nuts, I was always afraid she’d destroy it. I thought all her pictures were beautiful and I couldn’t understand what she was complaining about. But she’d lament: ‘It’s all wrong, all wrong!’

The South African painter Leon de Bliquy told her that painting wasn’t her strongest suit, but her ‘line’ was exceptional. She was an Expressionist at heart, he said. She had ‘angst’. She should devote herself to lithographs and wood and linocuts. He offered to teach her, but nothing came of it; it would have involved too much equipment and been too costly.

Of all Picasso’s oeuvre, she was most fond of his Blue Period – the fallen women and the pale, penniless artists. There was a print of La Vie on the big cork board in her studio and next to it Guernica. She also loved the pathos of Picasso’s Rose Period; his paintings of bony acrobats, forlorn harlequins, delinquent garçons, and itinerant saltimbanques.

Night Fishing at Antibes was my favourite Picasso. It was colourful and funny. At first glance it looked like something I might have been able to paint, except, copying it, one soon discovered it was the work of a genius.

My mom often depicted the labouring masses: roadside workers wielding picks in the sweltering heat; municipal workers bent and sweeping streets; a servant on her knees scrubbing floors; fishermen hauling in their teeming nets; women labourers in the vineyards staggering under the weight of baskets of grapes – the toil behind the Dionysian feasts she also painted. These pictures instilled in me at an early age an awareness, even a sensitivity for the downtrodden, which was unusual for whites back then in apartheid South Africa. She liked the down-and-outs – the beggars, the homeless, the waste pickers at the dustbins, the destitute people she saw, and the marginalised ones she imagined – gypsies, circus artists and street performers.

When Picasso died on 8 April 1973, I was five, but I remember how a pall settled on our home, as if an old and dear friend had passed away. The critical biographies of him that were published later my mom considered meretricious and scurrilous. Two of the main women in Picasso’s life, Marie-Thérèse and Jacqueline, as well as his grandson, Pablito, committed suicide in the years following his death. Had they found that they could not live without him, or were their suicides because they had been so indelibly damaged by him when he was still alive? Later, I would ask the same question about my mother and me.

We had a handful of books on classical Greek and Roman art, a few monographs of various sizes on Picasso, one on Leonardo da Vinci and one on Käthe Kollwitz. This last book was filled with the great Expressionist’s despair at war, even though the victims were German, a nation permanently tainted in the eyes of my parents because of World War II – ‘the bloody war’. Much later in life, my mother was slightly appalled that many of my closest friends were young Germans.

My mother drew caricatures of the Nazis – Hitler as a phallus, Göring as a beast with horns, Goebbels as a harp with a fork-tongue (I think she got the idea from Jack and the Beanstalk). She also tried her hand at sardonic anti-capitalist cartoons, drawing monstrous factories that looked like giant skulls, belching smoke, chewing up workers and pouring black sludge into rivers filled with litter and dead fish.

‘This is the hell your father has to go to every single day,’ she told me.

She did an ink sketch of a worker with his arm chopped off standing next to his wife and child. I could plainly see these were my parents. My father is begging with the hand he still possesses stretched out. The boss replies: ‘Sorry about your arm, old chap. Here’s your pay – 24 cents.’

I picked up the theme. I filled a whole drawing book with factories eating workers. ‘Dirty, capitalist, Nazi-pigs,’ I chanted. I was ten.

My mother painted about a hundred portraits, many of them self-portraits with double and triple profiles. One series was set to themes – praying woman, grieving woman, contemplating woman – but all were recognisable as her, even if she had three eyes and two mouths in some of them.

My mother’s maiden name was Morris, but she signed her pictures backwards: Sirrom. Apparently, Da Vinci also wrote backwards. Sirrom was her real self, she said, not Shirley Meersman and not Shirley Morris either. But which one was my mother?

‘You are all the encouragement, the only audience I really need,’ she told us. ‘And your father encourages me more than anyone on earth.’ She dedicated her paintings to us, writing our names in chalk on the back of the boards – ‘for Pauli’, ‘for Brent’.

Her pictures were the most precious things in the house to me. Her wild horses were my favourites, perhaps because I remembered a rocking-horse I had as an infant, but this might have been a memory planted by a photo my father took when I turned one.

She did many unflattering, cubist pictures of Papa; a few watery, sad, idealised ones of us kids, almost elegiac. She painted me in golden yellow watercolours, like an angel. But when I looked at it, it felt as if it was a painting one might have done for a child who had died. Besides, I was no longer that innocent boy. She had painted what had already passed by the time I was six.

There was one group of paintings she never displayed. She kept them behind a chest of drawers, stacked facing the wall. These were the ones she called ‘weird’. She said she didn’t wish to be reminded of them. But I couldn’t resist. When she was having a lie-down, I’d go and look. The boards were covered in paint – a wild, messy, churning palette of colours, muddied here and there – and she had etched into it with the back of a sharp object chimerical monsters, trees and rocks with unnerving faces, drowning wraith-like figures with their arms outstretched sinking to the depths of thick, green oceans. I was mesmerised by them. I could not understand why she hid them any more than I could fathom why she became angry with a beautiful picture.

‘What’s wrong with them?’ I asked. ‘They’re beautiful.’

She didn’t reply. She had a strange look – both wary and weary.

She shared her talent with us. She used the cardboard backs of her used-up drawing books and watercolour blocks to make colourful drawings of cowboys. She’d cut them out as paper dolls for us, each standing about a foot tall. The dolls argued and spoke to one another and had adventures together. I wasn’t making up voices for them but trying to impersonate the voices I imagined they already possessed. For me, her paintings had truly come to life. I tried my best to preserve the figures, but at some point, Billy the Kid, Wild Bill Hickok and Davy Crockett would inevitably get bent or torn during their wild adventures. I’d beg her to do some more. It could take a while before she could bend herself to oblige. I had to nag.

‘You can’t tell an artist what to draw,’ she’d say indignantly. ‘I’m not an illustrator! Commercial artists and fine artists are poles apart!’

But some years later, when I was nine, she did illustrate the stories I was then writing. I thought her pictures just as good if not better than the ones in the Biggles books I borrowed every fortnight from the library. She’d resist for a while. She’d say it was a question of inspiration, which was why she could never become a commercial artist. Art had to come from within; otherwise the figures came out all stiff and awkward.

‘I don’t paint fashionable, conventional stuff, or paint for money or to please people,’ she said. ‘You have to be fearless to be original.’

Everything she drew was gold to me. I’d be beside myself when she crossed out or tore up illustration after illustration which I wanted for my book. When she eventually gave me one, she would pronounce it: ‘Technically fine but devoid of life.’

I typed my stories on her ageing Olivetti. I had to sit on a box on the dining-room chair to get my little fingers above the typewriter keys. I wrote adventure stories based on what I was reading – Willard Price’s animal adventures; the horse stories of Mary Elwyn Patchett and Mary O’Hara; the exploits of Squadron Leader Bigglesworth by Captain WE Johns.

My mom had written a novel too. ‘A silly romance,’ she said. ‘Unpublishable rubbish.’ But relatives who had read Shirley’s book said the story was rather good. No one will ever know. On the ocean liner to Belgium in 1971, when I was four years old and we thought the family was emigrating, she flung the typed manuscript, the only existing copy, into the Atlantic. My father was furious.

Belgium, Papa’s birthplace – and Antwerp in particular – precipitated what for ever after was referred to as ‘the Belgian episode’.

The whole family would live in terror of a repeat.