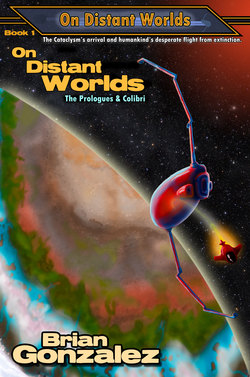

Читать книгу On Distant Worlds: The Prologues & Colibri - Brian Gonzalez - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Prologues

ОглавлениеTasaya Belocq

The Voyage of the Emissary

999 A.C.

Humanity’s motto in what were quite literally its darkest days seems to have been “Nobody Knows.” It was not in any way an official slogan. It wasn’t a popular catch phrase coined by the media, nor were people quoting a comedian or politician who famously used it in a speech. Those two words exist in the historical record any time there was a major discussion of the Cataclysm simply because they were true. The words were as true then as they still are when spoken today.

“Nobody knows what caused the Cataclysm”.

– Astronomer Hal Harris, The InterNight Show, 2056 C.E.

“Nobody knows what caused the other Cataclysm, either”.

-- Modern folk saying, used esp. in business and team sports after an unexpected and overwhelming loss

All these years later and we still don’t know what caused the Cataclysm; a thousand years of ignorance.

The obvious candidate was some sort of monstrous energy dispersal in the distant past; a titanic explosion which sent the ruined debris of dozens of star systems on a long and deadly path through space like a randomly directed shotgun blast of epic proportion. Whatever powerful forces in the ancient past precipitated the Cataclysm left no direct clues to their nature; their angry light had long since raced away and whatever ironically beautiful shell of expanding gas might have been left behind was either long attenuated and dissipated or beyond the considerable reach of humanity’s ability at the time to observe the universe around them. Nor was there even an attempt at an accurate estimate as to how long ago this event had happened; initially there was simply no clue to be had other than the fact that an enormous field of debris was rapidly approaching our area of space, moving faster than could be explained by known galactic processes.

“Nobody knows how big the Cataclysm will be, or how long post-Cataclysm effects will last.”

-- Secretary General of the United Nations, Dr. Kristina Shaw, 2051 C.E.

The limits of the rapidly approaching debris field extended beyond our ability to detect them. We wouldn’t even have known the Cataclysm was approaching had the debris field been more sparse, but along with the rocks and iceballs there was dust which was dimming the stars in a wide arc of the sky a little to the imaginary east of galactic center. It wasn’t anything dramatic like part of the sky going black; in fact, at first the dimming of those stars was not even noticeable to the naked eye. It was noticeable to computers, however, and those computers quickly calculated that the cause had to be what at first was called the Great Dust Cloud. We didn’t yet know the event would soon be renamed the Cataclysm.

The Great Dust Cloud of course became a subject of much interest in the sky-watching community, so the world’s astronomical interest was already focused in the right direction when the first occlusions occurred. It wasn’t just a dust cloud out there. There were moving solid bodies as well, large enough to measurably cut the light output from nearby stars. That meant objects the size of dwarf planets. With renewed interest the scientific community plunged into a full-scale investigation; and the results of their work, the famous Predictive Analysis of Incipient Meteoric Bombardment and Gravitational Disturbance, changed humanity forever.

The Great Dust Cloud was light-years wide and seemed to be composed of dust, gas, and solid bodies of varying composition: ice, rock, metal. It appeared to be the remnants of an entire region of space destroyed by some unknown force hundreds of millions or even billions of years ago. By cosmic cloud standards it was sparse and virtually unnoticeable; had you floated in the mathematically densest part of the cloud you probably wouldn’t have actually seen a single object or noticed any dust. Yet the objects were there, each millions of kilometers from its nearest companion, and there were an awful lot of them and they were headed our way.

But we had plenty of time to prepare. We had about eighty-five years.

This was the point at which the formerly named Great Dust Cloud became known as the Cataclysm.

“Nobody knows if we’ll get hit.”

-- United States Senator Chris W. Tomkins, explaining his “Nay” vote on the Cataclysm Act, 2061 C.E.

The odds of any individual object in the Cataclysm actually striking Earth were fairly low. In a perfect vacuum, Earth might not have been hit at all. But space is not a perfect vacuum. It includes things like planets and asteroids and comets and gravity. As the Cataclysm passed through the solar system it was inevitable there would be impacts, near-misses, and gravitational disturbances. Any object, even some of the smaller planets themselves, stood a chance of being significantly redirected. The great collection of icy bodies ensphering the outer fringe of the solar system would absolutely be disturbed, and if that disruption was severe and ongoing, then the odds of impactors on Earth went from fairly low to scary high.

Nor would this be a short-lived phenomenon. Primary disturbances such as native comets being disturbed by a passing Cataclysm body could occur at any time during the unknown number of years it would take the Cataclysm to pass through our stellar neighborhood. The gravitational changes they caused might take a very long time to fully play out; it was not at all unreasonable to expect impactors on Earth even centuries after the original disturbance. Whatever else, the regular rhythms of the solar system’s bodies, so thoroughly charted and understood over the last couple of generations of commercial expansion into space, would probably have to be largely rewritten.

Over the next decade we came to know a lot more about the Cataclysm. It appeared to contain an unnervingly large number of solid bodies, most of a size consistent with asteroids in our own system, as well as occasional larger bodies which some scientists named “Syncretic Massive Trans-systemic Asteroids” but which other, less polite scientists famously referred to as “the shattered remains of entire fucking planets.” It was the latter phrase which resonated with the public. Cataclysm dust itself registered as high in complex organic molecules, leading to some speculation that life-bearing worlds might have been destroyed in the event which precipitated the flight of this cosmic rubble through the emptiness. We had no idea how wide the Cataclysm might be; it was there for the dozens of light-years we could accurately scan, but after that it ghosted into the margin of error. So it might as well have been indefinitely wide as far as we were concerned, but after a decade of work we were able to calculate the Cataclysm’s approximate depth, and therefore the amount of time we would be subject to the effects of its passage.

Eighteen years. It would take eighteen years for the detectable majority of the Cataclysm to race through the solar system. A theoretical baby born during a theoretical first strike on Earth would experience a home planet under bombardment for his or her entire childhood and might even witness the last primary strike during a coming-of-theoretical-age party.

Then the adult that child had become could experience secondary bombardment for a lifetime.

The closer the Cataclysm drew and the closer we were able to study it, the more it became apparent that Earth was unlikely to escape unaffected.

One chilling problem was the sheer velocity of the objects. At their tremendous rate of travel even smaller objects became extremely dangerous, far more so than similarly-sized objects following long orbits in the comparatively sedate solar system. The Cataclysm bodies were essentially a curtain of incoming artillery fire cutting across the ballistic paths of the planets. It was true that we didn’t know if we’d get hit. But it was necessary to assume that we would, and hard.

And incredibly there was worse news yet to come. As the debris the Cataclysm carried drew close enough to Earth’s neighbors to be studied in relative real-time by our most distant assets, bizarre results started coming back from the ongoing observations. The dust seemed to register as existing sometimes, and other times as not being there at all. Sometimes the dust lightened the sky, and sometimes it seemed to darken it. For a while it was reported that the Cataclysm seemed to be speeding up, causing a wave of additional panic to race around the planet. Then it was reported that the Big Cat was not accelerating after all; it was an understandable miscalculation based on the fact that the approaching debris seemed to be increasing in size. That report was immediately challenged, and the two sides were still arguing when a third team reported that the Cataclysm was actually slowing down.

Then a fourth institution chimed in, reporting on their study based on mathematical analysis of changes in the distribution of energy in the observable wide-scale Cataclysm. They claimed that on average in the greater Cataclysm, the changes balanced so perfectly that in a sense the Cataclysm did not actually exist. Despite the fact that we were watching the Big Cat eat whole solar systems, nobody was ever able to find anything wrong with their math. But it would have taken observation of a much larger area of the Cataclysm than we could see to prove or disprove the set of equations.

“Nobody knows/If our race will survive/But our love will live on/As we look to the skies”

-- The Short-Termers, Thunk, 2110 C.E.

As it became increasingly obvious that humanity was facing what could very well be a global life extinction event, an emergency session of the Security Council of the old United Nations was held in New York. An agreement-in-principle to pool international resources for the purpose of developing a strategic survival plan emerged, along with a commitment for the funding to start the project, which became known as the CSP, or Cataclysm Survival Project. Offices were established at facilities in several nations and six months later the U.N. released its recommendations in the form of a three-point plan. Each point represented a different level of destruction caused by the Cataclysm - near-destruction of Earth, total destruction of Earth, total destruction of the habitable parts of the solar system – along with the recommended responses. The Plan contained no mention –no hope- of a future free of devastation and death. The Plan recommended that the majority of the world’s economic output be diverted for the purpose of humanity’s survival, essentially condemning what might be the last generations of humanity to largely be poor or –in the case of already struggling nations – poverty-stricken. The Plan relied heavily on theoretical advancements in nascent and unproven technologies. And the Plan flatly stated that even under the best circumstances, less than one in a hundred thousand people could expect to survive.

The CSP was explosively controversial. Assuming the total or near-destruction of the Earth as it did, it sparked a worldwide panic and angry backlash. Protests were held in almost every nation, some of which turned into riots, and a percentage of those riots went on to become insurrections or full-on civil wars. Some governments actually fell; others in order to survive withdrew from the United Nations, claiming they would handle their own preparations for the Cataclysm. Very few of those nations have much representation in the world today.

With the loss of funding from the countries which had seceded or which were embroiled in internal conflicts, along with the added expense of providing for refugees from the wars and assisting with security for the neighboring states, the Plan became economically tenuous. Cutbacks were made to each of the three sets of recommendations, and a robust Plan became a marginal one. Nonetheless, it was the only option humanity had and cooler heads managed to find a way to keep the necessary work moving forward through the opposition, the chaos, and the logistical difficulties inherent in a project so ambitious.

These latter were considerable. New technologies need to be investigated and developed on several intellectual fronts – human hibernation, nanosymbiotics, massive-scale orbital engineering –in a time of broken supply chains and frequent shortages of necessary resources. A worldwide organizational chain of production, quality control, and logistics had to be created and maintained in a political atmosphere of weak, divided national governments and an attitude among most countries of tepid support for the Plan in favor of immediate national interests. Even in some of the most advanced and liberal Western democracies, well-established research institutions crucial to the Plan sometimes found themselves fighting for mere existence against nativist forces in their own governments.

The first years of the effort were disastrous. Laboratories were opened and then shut down and sometimes reopened. Production facilities were picketed and vandalized and even bombed. A grassroots movement to stop the Plan, one of many but better organized than most, started drawing international appeal and organizing effective passive-resistance activities to perversely slow the effort dedicated to human survival. A key scientist and two major political figures were assassinated.

The next decade was not much better. Once a safe infrastructure was established, the predicted scientific advances were slow to come and when they did arrive, they proved difficult to implement in real-world conditions. Public and international support for the project continued to wane and opposition grew stronger, better organized, more effective. The last two years of this decade it seemed the Plan would collapse completely from lack of funding and physical facilities, but then the unexpected happened.

There was an economic boom.

The project itself was hiring more and more workers as it began new stages of production, each of which demanded both specialists and a generalized labor force. Each new stage also created multiple lines of subcontracted external employment to fill its specialized needs, be it the mining of rare earth minerals in the rain forests of South America or the designing of self-repairing smart metals in an office in Western Europe. Meanwhile, entrepreneurs who had bought into the Plan began founding companies to produce products and services complementary to the Plan; everything from clothing designed to last a lifetime, to underwater construction facilities, to family line DNA storage services, to the MyLifePods which sold almost fifty million units. The MyLifePods are still one of the most commonly found archaeological items today, often with the victims of their unfortunate software flaw still inside.

Twenty-five years after its inception, the project had become the largest employer in the world. Ten years after that and the majority of employment in the world was connected one way or another to the Plan; the activities of humanity revolved around it the way that for many generations the cycles of life in ancient Egypt had ebbed and flowed around the building of the Great Pyramids.

Humanity’s possible extinction was headed our way, but at the literal end of the day people still wanted to have a decent meal and a comfortable place to sleep. Better still if you could fall asleep with your favorite film playing all around you, a stacked bank account, and a hot new ride in your parking slot. As the various projects started paying for people’s lives, public opposition to the Plan began to wane. By the halfway point of the project, children were growing up into a world with actual enthusiasm for the Plan.

The departure of many moderates left the remaining opposition to the Plan much smaller, but now the zealotry and radicalism were more concentrated. They would still be heard from on a continual and sometimes spectacular basis, as we would painfully find out.

“Nobody knows if this will work.”

-- German soldier Jacob Grunner-Metz, the first human to undergo nanosymbiotic hibernation, 2069 C.E.

Point #1 of the CSP concerned itself with the partial or near-total devastation of Earth’s surface. It assumed moderate to heavy meteoric bombardment, with resultant long-term geophysical events: fallout winters, seismic and volcanic activity, disruption of the biological cycles that made life possible. And Point #1 worked.

The majority of humanity did of course die. Earth took three major hits along with hundreds of smaller ones. The planet’s population was decimated in the first three years, and halved in a decade, mostly due to starvation. It is estimated that fifteen years after the first strike, there were less than a hundred thousand people left alive on the surface of the Earth, most surviving in wave-powered floating habitats along the equator or in specially prepared caves or small artificially covered valleys in extreme Northern and Southern latitudes.

Underground, almost forty million people survived, along with hundreds of species of animals, thousands of species of plants, and the ability to – theoretically – bring back many of the species which had been lost.

A very small minority of these people survived in private shelters, dozens of types of which had been commercially available for decades before the Cataclysm arrived. Most of the individual shelters proved flimsy or poorly designed and prone to failure; those which were smart and rigorous enough to properly do the job they had been designed for tended to disgorge their survivors into a frozen ash-gray world devoid of living humans or indeed any other kind of biological support.

Those who lived in planned communities deep underground, particularly the Warrens, fared better. Cataclysm Studies was my Study of Minor Specialty in Second School so I have expertise in that area. I chose that Minor because despite the reality that living in the Warrens or presumably, the BioShip, represented hardship and deprivation, they were so cunningly designed for human needs that it was romantic in an odd sort of way. The ship and the underground communities also represented the triumph of the human spirit over the worst the universe can offer. As a young girl living under a warm sun and blue skies, eating fresh food and drinking natural water, I sometimes found myself wishing I lived in the Warrens, exploring the tunnels that linked the different underground habitats. Perhaps I would visit the farm, with its handful of live animals and actual crops under an artificial sun, or the school, or the food labs. Most exciting of all would be to take the days-long trip from the population habitats nearer the surface to the intentionally isolated and highly secured Future Bank kilometers below the rest of the Warrens, to see the square kilometers of art and technology and other cultural treasures of humanity all awaiting the future in one place.

That was a silly but frequent fantasy of mine until I turned thirteen. Then it and all other fantasies were replaced by the silly fantasy I just yesterday missed out on actually living.

Point #2 of the Plan assumed biological destruction of the Earth and the extinction of humanity on the planet. The Mars Colonies were enlarged and redesigned in an attempt to make them self-sufficient, and they included equivalents of our Future Banks. They didn’t store any art treasures or old vehicles, but they had full gene banks and, in crystalline storage, the collected writings and AV recordings of humankind. Additionally, a new class of food-producing space vessel was designed to provide a long-lived nutrition source for the isolated pockets of people living elsewhere in the Solar System – the Moon bases, the research stations on Jupiter’s satellites, and inside various large asteroids, the field HQ’s of the large trans-orbital mining corporations. Other than Mars none of these communities were expected to become permanently self-sufficient but rather just to hang on by themselves for up to fifty years as additional Future Bank insurance. In theory they would be able to communicate with each other and even provide mutual support in the form of launched supply packets, and in theory they could even repopulate Mars or Earth afterwards if humanity was extinguished on both worlds during the Cataclysm.

Unfortunately, none of these populations survived.

Mars took several hits. One colony was destroyed by debris raining back down from orbit after being launched into space by a Cataclysm strike elsewhere on the planet; Mars’s own rocks precipitating in molten form to sandwich the installation. Its remains are beneath a bronze statue and twenty meters of metamorphic basalt today. The other two colonies survived the Cataclysm itself, but enough damage was done to their infrastructure and to the environmental conditions of the planet itself that indefinite self-sufficiency became untenable. They hung on for generations, but eventually chose to stop reproducing and in 67 A.C. the famous Last Five held hands as they popped the hatch. By then most of the smaller outposts had died off; the Moon bases were ravaged by seismic tremors early on, and all the mining bases in the asteroid belt starved out except the NEOSpace facility, which was disturbed by a Cataclysm body and hideously flung off into outer space. The change in course is calculated to not have been violent enough to kill the population; what did those people do, I wonder, as they realized they were headed for interstellar space? There’s talk of sending an expedition to track the ill-fated asteroid, so perhaps someday we’ll find out.

Only the combined Jovian facilities survived for any length of time, an amazing feat given the number of gravitational and meteoric incidents in Jupiter space during the Cataclysm. The resourcefulness of a population of scientists and engineers, along with the protected positions of the installations themselves, on the far sides of their respective satellites from the giant gas planet and its potential radiation bursts, allowed the community to hang on eighty years. But they had shrunk from nine hundred people in fourteen facilities to fifty-three survivors in three damaged bases.

Fourteen of them died in the crash of the Lady Callisto in the attempt to land on Mars. The rest died out like the victims of the other space outposts; Karl Edgar Nassim wrote Last Human Standing in 88 A.C. and died in his sleep the year after. Given radio silence from Earth, from the BioShip, from Mars and from everywhere, it’s quite understandable that he really believed he was the last human being, and it’s what gives the work so much raw power. He wrote the collection of essays believing no one would ever read it.

Everyone has read it.

The third and most controversial point of the CSP assumed complete biological extinction not just in the Solar System but in nearby systems as well. If our own star system was rendered biologically inert by the Cataclysm, the reasoning went, there was no reason to assume any of the nearby and therefore reasonably well-known star systems would be spared a similar fate. To survive the worst-case Cataclysm scenario, humankind needed to become a space-based species for the indefinite amount of time it would take to find one or more hospitable worlds to sustain us.

BioShips would be designed and sent out into space, racing not directly away from the Cataclysm in futile attempt to outrun it but away and in courses perpendicular to the Cataclysm’s wavefront in order to, in great time, evade it. A sidestep maneuver.

In order to find planets which could lie hundreds of light-years away, the ships had to be self-sustaining. Even with the Plan’s projected advances in human hibernation paying dividends it would take multiple generations to reach other stars so the ships had to be generation ships, and in order to avoid creating cruel and harsh lives for those born en route and destined to play out their lives in the gaps between star systems a reasonable standard of living needed to be provided. What use preserving physical humanity if moral humanity was lost? The BioShips would be no less than discrete miniature worlds housing tens of thousands of people living in better conditions than much of humanity’s past generations and better than the impoverished citizens of their own time, many of whom objected violently to this point of the Plan.

Point #3 was audacious, forward-thinking, meticulously planned, and ruinously expensive. It would by far consume the most resources of any of the three Points, resources which otherwise might have enriched the lives of what might be the last generations of humans, the youngest of which had taken to calling themselves “The Lastest Generation” and which perhaps understandably felt a certain sense of sullen entitlement.

The opposition to the third point of the Plan was universally vicious and it was almost axed completely within a month of the Plan’s release. The Plan’s architects fought to keep the provision alive, dropping the number of BioShips from nine to six and then to just three. Their best efforts were not enough and a year later the third Point was indeed killed.

Thirty years later the shelved version was hastily revived, modified down to just two larger BioShips because there now would not be enough time or resources to complete and launch three. We were finally able to discern with acuity the actual effects of the Cataclysm wavefront solidly engaging several of our neighboring star systems simultaneously, a series of events which had occurred between five and twenty years ago. Every exoplanet we could observe was taking -- had taken – multiple hits. A couple of the systems were lighting up like a vidgame. The observed damage was far worse than models had predicted and the probability that our entire solar system might be devastated had just increased to panic levels.

In response humankind began the most ambitious project in its history; the orbital construction of two artificial worlds. When finished, the BioShips would be by far the largest artificial objects ever created, each larger than some of the smaller moons in the solar system, at least in terms of volume. Measured by mass they would be far less impressive, being composed largely of ice. But in terms of sheer size, only the world’s longest bridges and largest particle colliders would be discernible at that optical scale.

Of course only the one BioShip was actually built and launched. The second was already behind schedule when the fanatics bombed it. The ship was not destroyed but was knocked years off schedule and rather than leave the massive object (and its potential to become an incoming fireball) in near Earth orbit during the Cataclysm, they towed it into a four-month long plunge into the Sun.

We don’t know if the third point of the Plan worked. As expected, several weeks after launch the massive vehicle ignited the most powerful of its multiple propulsion systems, the radio signal-obliterating fusion drive, for a burn that was scheduled to last for months or even years if all went well. By the time they shut off the drive, if anybody on Earth was actually still receiving their signal, the record of such has not survived to our present day. Certainly the BioShip didn’t receive any signals behind that massive drive jet, but presumably at some point they would have looked back to see Earth darkened by the shroud of dust and rock and smoke and magma kicked up when Impactor One slammed into Eurasia.

Twenty very long years ago when they first announced the mission to follow the path of the BioShip and find any human colonies she might have generated, I knew immediately I was destined to fly that Jumpship. And I was in a perfect position to act on that goal: I already had my Second Degree in Cataclysm History and had already committed to Third School at the Andean Institute which had not just an excellent Jump Tech program but also a Leadership Academy and even a feeder program into the Security Forces. It was perfect, and I was convinced I was the right woman for the job.

I spent the next fifteen years of my life single-mindedly working to get into the Emissary Program.

Eight years of that was more public schooling, during which time I acquired a hard-won reputation as a top authority on the BioShip and her crew, and that got me into the Security Forces Academy with a junior commission.

Two years later I completed my flight training and performed my first Jump, the basic supply hop to Oort One. I piloted intrasystem for three years, then long-jump for two more, including twice to nearby star systems and once to deep empty space for multiple-hop testing. The Emissary mission would be the longest lasting and furthest-ranging mission yet attempted; we would be spending years out there and hopping many, many times. There was a lot of testing to be done, and I was there piloting a share of it.

I walked into the Emissary program with almost forty hops on my record, including several multiples and several long-jumps. I’d given up a lot to get there, essentially my entire youth. I hadn’t seen my parents in years, and I hadn’t been in a relationship or even had a fling in longer than that. The longest of journeys might begin with a single step, but the selection process for the journey involved a million. I’d spent every Saturday night for years studying or writing papers even long after I was no longer a student. But it had paid off. I was in the program, as I’d intended since I was so young it put a lump in my throat to think about.

I spent the next five years fighting to prove I deserved to be the pilot of the Emissary. And I failed. I didn’t even come in third in Primary Piloting. The fantasy I had worked toward for so long of being the one to pilot the Emissary on her voyage of exploration to other stars had crumbled. Others tested a bit quicker here, a little more consistently there. The Emissary program had done a good job bringing in top talent to compete, and some of that talent had kicked my ass. My dream of flying the Emissary into unknown star systems ended yesterday.

So if I had relied on only my piloting skills to get me named to the crew I would have washed out of the program right there. But I’m not unaware. I’d recognized the possibility I might not be the top Jump pilot in the world (although I admit not being top three stung a lot). So in addition to the contingency plan I had already executed, that of becoming a recognized BioShip expert, I had also put in the time and effort it took to excel in my secondary, emergency, and community skills. As much as my schedule allowed, I had attacked those other skills as though each was my Primary. While I’d come in fourth in my Primary, I’d picked up a couple of seconds in cross-training (small vehicle operation, tactical planning), had been top five in every category but one (field medical), and had earned the top overall cross-training mark. I could do over half the jobs on the mission, and nobody going knew more about the BioShip than I did.

They wanted me on the mission almost as badly as I did, and the way to accomplish that was to name me a Mission Specialist. It’s not “Lead Pilot” but it does have a certain cachet. I’m less disappointed than I might have been, because the job I actually did get has considerably more duties than the one I was trying for and I’m already getting overscheduled. Not much time for reflection or second-guessing. As my specialty I’ll be Chair of the BioShip Search Team tasked with finding the BioShip’s trail, a mystery I relish solving and which also puts me on the command deck at important times; it would have been so frustrating to be on the mission but only watching on vid below decks. I’m also on the Security team and the Damage Control team and the Colonial Contact team. I’m backup Surface Team leader. I’m backup Comm Tech. Community-wise, I’ll shift in the kitchen (all those weekend study nights cooking for myself), the Shuttle Bay, and Engineering (Maintenance), as well as helping edit the Emissary’s daily orders.

And best of all I’ll still get to fly. Perhaps an occasional Jump filling in for the regulars if I’m lucky, but more often, if all goes according to plan and we find the Colonies, getting the Surface Teams down to planetary surfaces safely. I’ll be flying the planetside shuttle. I’ll be the one who physically sets us down on distant worlds.

Davvit Tan

c. 3015 C.E.

To get the medical treatments which kept him alive, Davvit had to leave the Lobe once a month.

The pain generally came back about a week before the treatment was due. It started with a dull headache and stuffy nose. Overnight the headache would become severe and the abdominal pain would set in; these symptoms were manageable with tabs given him by his physician, Dr. Saito, and Davvit could still attend school. The last two or three cycles of that week would be lost to the pain, however. Davvit spent those days in bed; by the end of the week he was usually moaning in pain, even with nerve blockers. The abdominal pain was the worst, an unrelenting soreness throughout the trunk of his body which left him desperate to move to seek relief from the grinding ache. But if he did move, random parts of his torso would flare into full-on agony. Dr. Saito kept him well tabbed up during those times, including STM blockers so at least Davvit didn’t have to remember all the pain. To add insult to injury, by the time he returned from his treatment, he would be behind on schoolwork and would have to do double academic duty for a week when he ought to have gotten extra time off to recuperate. But school was strict that way; if you were of sound mind, you were expected to keep up. Life on the Ice-ship was tough, so school wanted you tough.

If Davvit was lucky, he got two weeks between treatments to be free of both pain and extra work.

Even as such, his life might have been tolerable but for his classmates. They hassled him constantly, not just because Davvit’s illness left him smaller and weaker than the other boys but also because he was an orphan who lost his parents in the big accident some time back. “What are you going to do,” a classmate might ask while twisting Davvit’s arm painfully behind his back, “Run home and tell your mother?”

“Your parents killed themselves to get away from you!” was another class favorite.

That was the point at which Davvit usually hit them in the nose. His punches were not meaty enough to seriously hurt anyone – a couple of the burlier boys would actually laugh at his effort -- but he suspected it kept some of his milder classmates from teasing him as often as they might have otherwise. Nor could anyone fight him back in any serious sort of way; beating up a person who had a serious illness was a sure way to land in the brig for a month or so. Davvit had more than once previously attempted to draw out a scuffle in the hopes of getting a particularly nasty classmate, Herk, arrested. But the bullies were too canny to be drawn into his trap. They struck like rumors, hitting him in dark and empty places and disappearing before raised voices or the sounds of a scuffle could attract attention.

Davvit’s long-term strategy to deal with his life was a simple one: wait for age seventeen. By age seventeen, the doctor assured him, he would outgrow his illness. Furthermore, as they graduated school the students would disperse. Some, as Davvit intended to do, would go on to college for advanced studies. Most would take ordinary jobs or join the Authority Peacekeepers. A few would struggle to find their place and end up addicted, arrested, or killed. Davvit hoped Herk would end up in this category. One way or another, after graduation it would be rare for Davvit to encounter his former classmates and that was a time he looked forward to with great anticipation.

But today he was still in ninth grade and it was time for his treatment. That meant a two-hour journey to the Medical Center in Authority Lobe 1, at the front of the Ice-ship. The first time he’d made that trip, back when he was eight, it had been new and exciting. It was rare for kids to see other parts of the Ice-Ship; even adults, unless they were Peacekeepers or involved in the running of the Ship itself, spent most of their lives in just one Lobe. Davvit had looked forward to that first visit despite his pain and in fact when the word got around some of his classmates showed actual jealousy, a situation wholly unknown and rather pleasing to an ill and undersized orphan. For a week his fellow students had pestered him about it, some asking questions about his illness and treatment, questions Davvit didn’t answer because, after all, it was none of their damn business if he had IDCS (Interstellar Disrupted Cell Syndrome). It wasn’t contagious.

The majority of his classmates saw Davvit’s condition as just an additional way to torture him. They made up stories to terrify him. Mary told him the treatment would make his testicles shrivel and drop off. Micah claimed secret knowledge that no one ever came back from the Authority Lobe after medical treatment. Sissa, whom Davvit secretly liked, claimed the path to the other Lobe was full of monsters; chupes, the escaped genetic experiments that would hunt you down and suck your blood, ice ghouls, which scream in the night before they haul you off to eat you, and shamblies, the walking dead. Herk, already well down the road to sociopathy at such a tender age, had told him the Authority was just going to put a bullet in the back of his head.

Intellectually, Davvit knew that none of those things could be true. Certainly they weren’t going to execute him; he hadn’t done anything wrong and if they were planning for no discernible reason to kill Davvit, why were they bothering to educate him? And – in the daytime, at least – he didn’t believe in chupes or ice ghouls or shamblies. Those were little-kid stories. Yet he couldn’t help feeling chilled as that first visit neared, especially in the night-time. He even asked Dr. Saito why the medical treatment couldn’t be performed in the Lobe hospital instead of travelling to the Authority Lobe.

“Controlled technology,” the doctor told him. “The tiny robots they’ll be using to help you aren’t allowed in the civilian Lobes. So we have to take you where the robots are.”

They’re nanites, not robots. But Davvit didn’t bother saying it. Dr. Saito was a good guy; he couldn’t help it if he didn’t have children of his own and was unsure which words kids would understand.

After the fearful anticipation, after the horror stories and the dread and the hope; the journey was utterly ordinary. They rode the Medical elevators up to the top level of the Module, where they waited for what seemed a very, very long time for a quarter-to-the-hour to arrive. Davvit was in a lot of pain at this point; he hunkered down in a chair and tried not to cry as the minutes passed by with literally agonizing slowness. Finally, as it did every forty-five minutes, the entire level then disengaged from the rest of the Module by retracting its accessways and the massive titanium-alloy pins which normally secured it to the rest of the Module. The magnetic induction plates which spun the Module then reversed on the top floor only, gradually slowing and then stopping the spin of the discrete level. Davvit and the doctor and nurse, along with the other waiting passengers, floated in the sudden microgravity through narrow access tunnels which slid them neatly into the waiting vehicles.

They rode the same ancient, creaky and graffiti-covered rail sleds one rode to go anywhere. The rail sleds had only one forward window which was inevitably pitted and starred and slightly hazy, so it was difficult to look through them at the walls of the transport tunnel. The tunnels ran through the interior of the infrastructure struts and building braces but there were occasional places where there were windows in the tunnels; there you could look out and see the sights of the Lobe interior: the lit buildings spinning on their braces, the distant cool glow of the ice-farms, perhaps even a work crew flitting by in a compressed air-powered work pod. Like all children Davvit loved looking out the windows at his homeland, but between the pain and the dismal condition of the window there was little joy to be had from sight-seeing on that trip.

In the increased security of the Authority Lobe, there were no tunnel windows. There was also the question of dealing with sudden and unfortunate nausea. Between the pain and the meds, Davvit found himself retching as they passed through the various gravity gradients on their way to the Authority Lobe; as they transited the central core of the Ice-Ship where gravity was essentially non-existent, he actually threw up. Gravity sickness like a little baby! It was humiliating, but at least Dr. Saito and the accompanying nurse acted like it was quite ordinary, vacuuming up the floating stinky globules and applying a cool cloth to his flushed skin.

The Medical Center in the Authority Lobe looked exactly like the hospital in his own civilian Lobe, of course. That was as disappointing as the trip. Davvit didn’t know why he had expected anything different; the key structures in each Lobe were of course identical to each other.

He was there for three cycles of which he remembered very little. They sedated him for the actual treatment; he had a few vague memories of waking up and finding himself in bed and hooked up to various pieces of intimidating equipment. That was the first two cycles; the third cycle was recuperation. Davvit spent all day either lying in bed, marveling at the fact that he could actually move without pain and watching old movies on vid, or standing in front of the toilet pissing out dead nanites. That part did hurt a little but Davvit didn’t mind. It was minor compared to that of the previous week. The next cycle Dr. Saito returned them to their home Lobe; the same long boring trip in an ancient, beat-up sled, but at least Davvit didn’t have to vomit this time.

He’d made that journey dozens of times since. The journey was always the same dull, nauseating trek and the treatment was always the same vaguely recalled deep misery; only the Authority doctors who were assigned to him or the actual room he was treated in ever varied in any way.

He was sick of it. But it was time to do it again.

Davvit had no way of knowing this time would be different.

The strange thing didn’t happen until the recovery cycle of his treatment. Davvit must have awoken from sedation earlier than usual – he was in his mid-teens now, and perhaps the doctors had not adjusted his sedation doses well enough – to find himself alone in a dark recovery room. Every other time there’d been a nurse there, patiently awaiting his return to consciousness, usually reading or doing pad-work in a well-lit room. He glanced at the clock display on the biometric readings pad attached to the back of his left hand; it was the middle of the night. He still felt a bit woozy from the sedation. Light-headed but heavy-bladdered; he desperately needed to piss out some nanites.

“Lights,” he said and the room dutifully flickered on a few of its ceiling panels. The room was new to him but familiar: a small, spare room, with banks of mostly inactive medical gear on the wall behind the headboard of his bed. Opposite the gurney he occupied there were two identical doors in adjoining walls; one would lead to the hallway outside; the other was hiding the fixture Davvit’s bladder was seeking. Davvit disconnected the single lead from his biometric pad and gingerly swung his legs over the side of his gurney, but there was little pain. He stood up and swayed a little, adjusting his balance to the remaining effects of the sedatives. With no nurse to guide him to the bathroom as usual, he optimistically chose the nearer door, the left one, sliding it open and stepping through as his bladder cheered him on.

It wasn’t the bathroom; it was the hallway. The recovery rooms formed a horseshoe configuration surrounding a central nurse’s station; Davvit was standing slightly left of center of the base of the horseshoe and looking at the nurse’s station which was, for the first time in the years he had been coming here, unoccupied. He could hear urgent-sounding voices from somewhere up the hall leading off to his right. Some other patient’s recovery must not be going well. A fresh twinge from Davvit’s bladder, and he darted back toward the bathroom door.

Passing nanites was never fun but this time it was alarmingly different. His urine felt even more syrupy than it usually did after treatment and it was bright pink and foamy instead of the usual blackish-gray. And it smelled, sharp and unpleasant as bile. As his bladder relaxed with physical relief, Davvit’s mind shrieked with fear. What had gone wrong? Had they messed up his treatment? Was he in danger? Was he dying? He needed to find help. He finished and started to flush, then decided against it in case a doctor might need to see the scary mess. He hastily refastened his smock and closed the bathroom door as he left; no need for that odor to permeate his recovery room.

There was still nobody at the nurse’s station, so Davvit returned to his room to use the call button on the side of his gurney. Several fearful minutes passed without any response before he realized with chagrin that the call button was probably signaling the empty nurse’s station. He needed to go find a doctor or nurse himself. Once again he walked out to the nurse’s station, and this time headed for the raised voices up the hallway past the central station. The nightmare happened as he turned the corner into the hallway, a moment after he thought he heard a shout and a moment after he heard approaching footsteps and dared hope it was the nurse.

The figure he almost collided with was about Davvit’s height; in other words, as small as an undersized and chronically ill teenager. It was wearing a smock like Davvit’s, only this smock was stiff and crusted with biological stains; some reddish-brown which were probably dried blood, others were greenish or yellowish caked encrustations which Davvit did not care much to guess about. And that was where the tolerability of the situation ended, for the person wearing the smock was like no presumably living thing Davvit had ever seen.

The figure was hunched over, too far so for the face to be visible, but it was male if the pattern baldness meant anything. A man, then; a tiny, withered man. His skin hung loosely wrinkled on his bones and was horribly discolored, liver-spotted with large purple-black patches on the arms and face. Some of the patches appeared to be oozing fluid. Otherwise the skin was greenish or ash-gray; Davvit had no idea what color the man’s skin might have been originally. In places the skin was missing completely and Davvit could see raw, rotten-looking flesh underneath. Near the back of the head it looked as though actual skull might be showing through.

And the smell! Davvit gagged as the figure’s miasmic aura reached him; it was the smell of decay, of rot, of mold, of death, and bizarrely, of Thursday night teriyaki in the Module Citizens’ Café. Davvit was never to eat there again. His gorge rising and terror clutching at his gut, Davvit fell back even as the figure laboriously lifted its head on a thin neck mostly wattle and cancer to look at him, and the face, the face… the face was what made Davvit lose his mind. The eyes in that face, so cataracted they looked like sinew. The bare amount of rotted flesh on that face, leaving the shape of the skull intimately visible. The missing part of the face, exposing yellowed cheekbone and black veins and tooth roots and bone bubbled with tumors. The way a small part of the remaining flesh on the left side of the jaw, apparently disturbed by the creature’s effort to turn its head upward, slid slowly and haltingly off that face and fell with a greenish double splat to the deck below.

It was a shamblie. What else could it be? It was a shamblie. There was shouting from behind the thing. The shamblie. Down the hall there were people pursuing it and they were not doctors or nurse but Authority Peacekeepers in combat gear and carrying rifles. They were yelling at Davvit to get away but it was too late. The shamblie opened its ghastly mouth and issued an inarticulate cry of rage, and then lunged at Davvit with its skeletal hands. Davvit, his defensive skills honed by years of necessarily exercising anti-bullying tactics at school, parried the thrust with his forearms, and shrieked and ran. He ran as fast as he could, back around the nurse’s station and up the other hallway. But the hallway dead-ended at a locked door marked “Authorized Personnel Only”. His back to the wall, Davvit listened to approaching footfalls and raised voices while he planned his last stand. He could not see a way to quickly become Authorized and escape through the door. He would have to drop and roll, taking out the shamblie’s legs, and then run like hell toward the Peacekeepers.

The shamblie turned the corner. Spotting Davvit, it croaked out a dry scream and lurched toward him. A Peacekeeper was right behind it. Davvit watched with nascent hope as the man brought his rifle up to his shoulder, steadied himself, and aimed.

And then the Peacekeeper shot Davvit in the chest.

Everything went black.

Davvit woke up in his recovery room.

What the hell? Davvit sat up and looked around. The lights were on. A bored-looking nurse was sitting beside his gurney, jotting notes on a clipboard. Her nametag read “Marjorie June”. She sensed Davvit’s motion, looked up at him, and jerked her thumb toward the bathroom door. “You know the drill,” she said.

“But…” Davvit’s mind balked at the idea of normality. “What happened with the shamblie?” he blurted out.

Marjorie June peered at him closer, seeming to actually see him for the first time. “The shamblie,” she repeated with amusement. “You had a tough time during the night, Davvit. Lots of tossing and turning, unusual for you. Lots of high-level brain activity under sedation, unusual for anyone.” She waved her clipboard at him as though somehow the up-and-down motion would transmit data about his past procedures into Davvit’s head. “I can see how nightmares about shamblies would have caused a little sleep anxiety. But that’s over now.”

“It was real,” Davvit said. “There were Peacekeepers. One of them shot me!” He clutched at his chest only to realize there was not a wound there.

The nurse smiled at him. “We don’t have Peacekeepers in the Medical Center, Davvit, and if we did, they wouldn’t be shooting our patients. We want to make you better, not dead.” Suspicious, Davvit scanned her face for dishonesty but as far as he could tell – and as a frequent target of bullying, Davvit had developed fairly good instincts about people’s intentions – Marjorie June was being completely truthful and seemed genuinely concerned about him.

Confused, Davvit took a moment to consider his situation. As Marjorie June had pointed out, he did not appear to be any kind of dead. The room, the nurse... in fact, the way he felt right now, post-treatment miserable, all seemed perfectly normal. Could it in fact have been a dream? “I have to pee,” he finally said.

Marjorie June jerked her thumb toward the bathroom door. “You know the drill.”

When he opened the bathroom door there was no sharp tang of medical waste. In the toilet bowl, only “clean” recycled non-potable graywater as always before. When he pissed the flow was its usual thick gray-black, full of dead nanite husks. Everything was normal. Could it really have been just a vivid dream? Damn Sissa and her time-release horror stories, anyway. And with the thought of Sissa came thoughts of school and thoughts of missed assignments and upcoming grade exams. With a weary sigh, Davvit washed up and thanked Marjorie June, who decorously left to allow Davvit to get dressed.

He of course talked to his own doctor about the incident during the trip back to the Civilian Lobe. As Davvit’s primary physician, Dr. Saito transported Davvit back and forth to the procedure as per often-complained-about regulations but returned to his own practice while Davvit underwent treatment. But Davvit had felt too stupid to ask Marjorie June to see a doctor there, so he would just have to get what answers he could from a doctor that he actually trusted. Could he really have had a dream that vivid during the treatment? “Oh, sure,” said the doctor. “For a lot of reasons, actually. You could be developing a tolerance to one or more of the medications. Or they might have used a different combination of medicines which might mean a previously unknown interaction; I’ll review your records. Allergies. Puberty. It could even be something you ate.” He looked at Davvit appraisingly for a moment, and then said: “You’ve proven yourself a practical and serious young man, Davvit, so I’ll be honest with you. The reason they give you short-term-memory blockers during most surgical procedures is so that later you have no memory how absolutely flipping high you got. The best explanation for what happened to you would be that the STM’s didn’t work long enough for whatever reason and you’re remembering drug-induced dreams or even full-blown hallucinations you ordinarily would have no memory of.”

Unlike the bizarre explanations he’d considered so far -- impossible reality or unbelievably real dream -- this one actually made a fair amount of sense. Davvit tested the idea for flaws as their transport sled rode its single rail through the tunnels of the Ice-Ship. The motion of the sled disguised the actual moments they were weightless, but there was no mistaking the shift in the general pull of microgravity over several minutes, up and down flipping places, like the directions themselves were orbiting you. After treatment gravity gradients were actually fun again, like they were supposed to be. Accepting Dr. Saito’s hypothesis, Davvit turned his attention toward school and what creative counter-insults he might need to arm and launch tomorrow.

And all was well until later that afternoon, after he checked out of Dr. Saito’s office and headed back home.

Davvit lived in the Crèche, which of course was where babies are born, which of course was just more ammunition for Herk and his type to taunt him. Never mind that Davvit had a small suite of his own; parented children left the Crèche but orphans or children needing constant medical care – and Davvit fit the bill on both counts – remained behind, living in age-appropriate quarters. Davvit had more space and privacy than most of his schoolmates. A Crèche Parent checked on him at least once a day and the Parents were always available when needed, which was also a lot more than he could say for some of his classmates.

In a couple of years he would be eligible for his own small quarters, a year or so ahead of the parented who had to fully finish school first; let’s see what Herk had to say then. But in the meantime the Crèche was his home and by no coincidence happened to be on the floor below Dr. Saito’s offices. The medical staff allowed him to use one of their internal access ladders; otherwise he would have to return all the way to the central spindle of the Module, wait to ride the platform just one floor, and then walk all the way back out to the Crèche’s location on the D-wedge of the Module. The ladder, on the other hand, let him out thirty meters from the Crèche.

Davvit climbed down the ladder that led to home. As he hand-over-handed down the rungs, he caught a faint but unmistakable odor every time his left wrist neared his face. He paused mid-ladder and sniffed at his left arm, frowning. Most of his arm smelled like mild antiseptic, but a tiny patch near the outside of the wrist smelled of decay and death and rot, a faded but accurate representation of the walking horror he had unquestionably experienced last night.

It was like somebody had missed a spot when they cleaned him up.

Author Unknown

“Top Ten Misconceptions about the BioShip”

Cataclysm Humor Net Locus

2101 C.E.

#10: It has weapons in case of aliens.

Sure, the BioShip is loaded with weapons. Big surface microwave lasers and whatnot. Heat beams. Missiles. But they’re not for aliens. Picture the BioShip moving through space really fast. Now picture a huge asteroid moving through space really, really fast. Now picture them slamming into each other. Get a third picture clearly? The one where the asteroid punches straight through the BioShip and keeps going? Those weapons are to protect the BioShip from regular space hazards.

But wait, you say, because you’re a doon, what about the machine guns and handguns and such? Aren’t those to repel boarders? No, you doon. Any time you have more than, say, one people in one place, there’s going to be violence. The weapons aren’t in case of aliens. They’re in case of humans.

#9: Everybody Will Be Frozen All the Time

Horseshit. There will be 2 kinds of people on the BioShip: Civilians and Authority. Only Authority personnel will ever be “frozen” (see below) and only top-level personnel at that. It’s just to make sure there are always people around who actually know how to run the BioShip. So please stop repeating those stupid fucking “space morgue” jokes. (Yes, we know we helped start the trend. We were young and naïve. Remember we’re all dead soon anyway and shut the fuck up.)

#8: People Will Be Frozen At All

For the last time, they won’t be frozen. They’ll be in a superchilled, electrically stimulated, genetically active biological gel full of heat-exchange-powered microscopic robots. Does that sound like the same thing you do to Aunt Edna’s pot pie for three and a half years before pitching it into the trash?

#7: It’s an Escape Pod for the Rich

Well, yeah, the rich are getting onto the short list in kind of disproportionate numbers. We’ll admit that. So it stands to reason they’ll get on the Civilian roster in similarly disproportionate numbers. But remember this: the BioShip won’t actually use money. So as soon as the rich board, they become as poor as you and your flapmates. They’ll get no extra privileges and in fact will have to work. Nasty, nasty work (not that we personally would know whether real work is nasty or not, but we assume it is because it sounds nasty). So it’s not an escape pod for the rich. It’s hell for the rich.

#6: The “PreFab Colonies” Are Already Built

You doons can make whatever choices you like, but we here at Cataclysm Humor would not care to ride down to the surface of an unknown alien planet on rubber O-rings that had been kept at low temperatures for, oh let’s say four hundred fucking years [BlinkLink Challenger Disaster] and we think the actual colonists will feel similarly not stupid as shit.

The shuttles and colony structures are predesigned but will be built from raw materials on the way so that they are new and trustworthy when they are used.

#5: It’ll be Like Working in a Submarine Your Whole Life

We’d love to see the submarine that includes schools, concert halls, zoos, low-gravity swimming pools and gyms, parks, wingflight facilities, sports arenas, hospitals, an artificial mountain to climb, and the ability to make its own smaller submarines. We’d love to see that submarine so much we’re going to go out and look for it right now. And when we find it we’re going to kill the people who have it and take it for ourselves. Then we will quit working at Cataclysm Humor.

#4: It Will Be a Police State

Everything is a police state. That stipulated, the civilians will govern and police themselves. Authority cop/soldiers (or as we like to call them, Pigtroops) will only have jurisdiction in civilian areas insofar as the safety of the BioShip itself is concerned. Say you tried to set off an incendiary bomb in a civilian area. A civilian cop or an Authority Pigtroop could arrest you. But say you stripped yourself naked, slathered hot sauce on your member, violated a copyright, put laxatives in the water supply and then performed a human sacrifice in front of a squad of Pigtroops in a civilian area. The Pigtroops could not arrest you. They could conceivably squeal and wallow in their own filth and perhaps even throw excrement at you. But they could not arrest you.

#3: It’s Made Out of Ice

It’s a starship. It’s made out of metal and plastic and ceramics.

The hull of the BioShip is the part you could chisel at to chill down your Pomegranetini. Theoretically. But you wouldn’t really want to do it because it’s not just ice. It’s ice blended with the raw materials the ship will need in the future. Metals, minerals, chemicals; lots of stuff and some of it pretty poisonous.

But – stay with us here – if you were to tunnel down through dozens or even hundreds of meters of ice (depending on location) and managed to get to the inner layer of the outer hull… that part actually is pure ice. They don’t want the ice-resources blend next to the Habitation Lobes. The pure ice layer prevents cadmium poisoning or whatnot. In fact they plan to farm the ice. So if you took some for your Santa Margarita you would be arrested, possibly by cops, or more likely by angrily snorting Pigtroops.

#2: It’s Code-Named the Ice-Ship

It just sounds like “Ice-Ship”. It’s actually “I-Ship”. “I” as in “interstellar”. “I” as in “incredibly stupid mistake”. “I” as in “Interestingly, I am filling up with generalized rage”. “I” as in “I just want you to shut the fuck up now”.

#1: It Won’t Work

Of course it’ll work. Lots of smart, well-trained people with all the resources and energy they could possibly need will be running this. The most brilliant minds of the last two generations planned it. Why wouldn’t it work? Of course it’ll work. The question is: how long will it work? Will it work long enough to sidestep the Cataclysm and find us new homes, traveling light-years away over hundreds of years? Or will it work only long enough to kill all the passengers in slow misery? Nobody knows. But one way or another, when they hit the switch, something will happen.

Next time: What if the Cataclysm advertised? (Reader Contest Results)

And remember, we’re all dead soon so shut the fuck up.

Jennifer Antonov

c. 2181 C.E.

Today was the third day in a row they had been forced to break camp before 0500 hours.

The first Enemy hoots had sounded less than an hour ago and already the humans were hundreds of meters away from last night’s camp, hacking new trail through a gentle downslope of spiraled yellowish grasses and dark purple frond-plants with meter-wide stellate leaves and tough, woody stalks as thick as her thigh. It was tough going and Jennifer would have given anything for a fully powered cutter. A flick of the switch, a tang of ozone, and ugly foliage would have parted before her like she was the extraterrestrial female Moses. But cutters belonged to the past. Like Saturday night dances and access to the Net. There were only three energy cells left and they would be needed in the future. Machetes and the blisters that went along with them were all the rage these days. The technology has to match the times.

They had broken camp in about twenty minutes today, but she wasn’t sure whether that was because forcefully imposed practice was making them more efficient or whether the losses they had taken in the last week made the camp that much simpler to break down. They were down to twenty-two people now, and three of those injured badly enough they couldn’t blaze trail or patrol. But you couldn’t fight a moving siege through unknown terrain without casualties. The Last Standers were dwindling fast.

Under ordinary conditions it would have been easy to outpace the poorly organized Enemy pursuit. But the specific nature of their mission made that impossible.

Half a klick behind them, a short, flat report sounded, followed by cheers and fist-pumps from some of her fellow Last Standers. The Enemy had set off one of the booby traps left behind at the camp. A minute later there was another blast, but then no more. They had left behind a half-dozen of the irreplaceable jury-rigged mining caps. Less than a half-case left now.

At yesterday afternoon’s planning meeting, the War Council had agreed to try to pick up the pace a bit today in the hopes of giving most of the party a good long sleep period on the other side. That optimistic plan was to fall to pieces less than an hour after the booby traps detonated. The advance scouts, Tony and Jessie, suddenly appeared at the head of the trail, looking grim. “Living gully,” Tony said disgustedly.

It was one of the largest and healthiest living gullies Jennifer had ever seen. Its biological control zone, the area where the local plant life was excluded by the thick carpet of toxic tendrils, was fully nine meters across on each side of the spine-line, about twenty meters across in total, and disappeared into the foliage in both directions. The crack which housed the spine-line of the colony was only a half-meter wide, a zigzagging volcanic crack which would be deep and twisted and would afford excellent protection to the communal nerve-sheath and the colonial thropes it had budded. The thropes might number in the hundreds or more, to judge by the size and length of the tendril mat. This gully might be centuries old. Just from where she stood, Jennifer could see at least a dozen mat-lumps in various stages of decomposition; the remains of foolish animals who had ventured onto the tendril mat in search of food or mates. They had died there, alive for days or weeks as the tendril mat digested them from the outside in.

“To the north it runs up into a sheer rock face,” Tony said. “To the south it cuts back the way we came.”

“Well, shit on a stick.” Captain Anders took off his helmet and used it to shade his face as he peered more closely at the gully. “Too wide to bridge and no way to circumnavigate. We’re going to have to burn through. That’ll cost us our lead.”

“It’ll take two, three hours to burn through that,” said Aram Lewitt. A field research biologist before the fall of City, he’d had to deal with living gullies before.

The Captain came to a decision. He took Aram by the arm and led him a few meters away where they spoke in low tones, each of them occasionally gesturing at the gully. The gully itself seemed to have sensed activity in the area; some areas of the tendril mat were starting to twitch. Jennifer took a drink from her water bag and squinted up at the sky. Thin strips of cirrus cloud were visible to the east; the same formation they had been following for days but now much higher on the horizon. If the Last Standers had not run into this gully it would have been only another day or two of travel to crest the Southwest Ridge.

Everything would change when they crested the Ridge, and favorably so. They would be moving constantly downhill instead of struggling with the variegated terrain they had been crossing the last two weeks. The temperature would start dropping and humidity would increase, more so with every day of travel until they hit the precipitation zone. Once they reached the permanent rains, the Enemy would be completely out of their element, struggling to keep themselves warm and fed. Reach the rains, and there was every reason to believe the Last Standers would take over the terms of the engagement and successfully fight their way onto the ice.

But there was still the gully to deal with before Jennifer and the others would get to see the thunderheads of the precipitation zone. The meeting was over between Aram and the Captain; the former researcher started unloading tools from one of the carry bags attached to the two-person yokes the team had been using since their last cart went down. The former policeman returned to explain what their strategy would be. “One way or another the Enemy is going to reach us before we finish burning across this gully, so there’s going to be a firefight. But if we just burn through and run, the Enemy’s going to be right on our asses the rest of the way and that is not an acceptable situation. Aram and I have worked out an idea that might preserve some of our head start. But it means we’ll be here for quite some hours so we’re going to go ahead and establish a defensive perimeter 200 meters down our trail and engage the Enemy there. ‘A’ Squad, let’s get that started. ‘B’ Squad, establish nutrition and rest stations, then report to Mr. Lewitt for gully-burn instructions.”

Jennifer was ‘A’ Squad, so she along with Anders and four others, including the scouts, headed down-trail with weapons and bags of equipment. Two hundred meters back the way they came Jennifer saw why the Lieutenant had chosen this spot; there were rock outcroppings for cover and to the west the ground fell away slightly, minimizing the cover the twisted grasses would offer the approaching Enemy. As they started laying wire and checking weapons, an Enemy hoot sounded, and it was not terribly far away.

Twenty minutes passed before the Enemy arrived, twenty minutes during which smoke started rising above the foliage to their rear flank, thin and gray at first but soon enough thick and dark and acrid. The smoke naturally blew directly across ‘A’ Squad’s position but there was no avoiding that. The wind blew the only way it could: inwards from the atmospheric vortices beyond the precipitation zone. It had been that way for millions of years. It would always be that way.

The first Enemy to arrive were usually aggressive first-year males instinctively seeking to establish their own troops and this time was no exception. They appeared in ones and twos where the Last Standers’ trail faded over a rise about forty meters away. There, catching sight of the human defensive emplacement, they faded into the grasses and chattered and shrieked ferociously. They were waiting, not so much for numbers as for the emotional pitch of the group to reach the boiling point that led to a charge. This would happen when they had numbers. Two of the Enemy carried sticks – whether spears or clubs Jennifer did not have time to see. Another may have had a knife. And one had definitely been carrying a rifle.

“Did you catch that?” Jennifer whispered to Captain Anders.

Anders nodded. “If he’s had it any length of time, it’ll be discharged. But we have to assume he just acquired it.”

They waited. Behind them the smoke from the gully burn thickened. It was still blowing toward their position but at least it was to their backs; the Enemy would have the smoke in their faces. ‘A’ Squad drank water and tried to stay calm. The Enemy gathered. Above them all the huge red sun clung to its one spot in the sky.

The attack began with a single Enemy shrieking and charging up the trail at them, fangs bared and waving a stick. Not one of the smarter ones. Tony dropped him with a single shot. But the sound of the gunshot, as well as the sight of one of their number dropping dead in the middle of the trail, galvanized the rest of the troop to action. With a group chatter, they charged. Maybe a dozen of them. Some came straight up the trail but others advanced parallel to the trail in the grass where they were a lot harder to see.

The Last Standers opened fire. The handful of Enemy who had chosen the trail were cut down immediately, small furry bodies cut in half by semiautomatic weapons fire or sent flying backwards the way they had come, internal organs liquefied to jelly by the single remaining pulse rifle.

There was a responding gunshot, answering the question of how long ago the armed Enemy had found or stolen the rifle. The round smacked wetly into the thick stalk of a frond-plant at the edge of their perimeter, not that far from Tony, who flinched away. Not only was the rifle active but apparently the Enemy male had some idea how to use it. As if to confirm this point, the rifle spoke again and this time the shot winged directly over the center of the emplacement, missing everything completely but in truth much better-aimed than the first.

“Take him out,” yelled Captain Anders and everyone opened fire on the rifle’s position except the two people anchoring the ends of the line; they were raking the grass with automatic fire, keeping the flanking Enemy pinned down.

The patch of grass from concealing the enemy gun flattened from a pulse gun blast to reveal a surprised-looking Enemy male, caught halfway through pumping another shell into the chamber. Ignoring the bullets ripping past him, the Enemy snarled at them, his little black eyes glittering, his sharp teeth snapping twice, and completed his reload. The rifle was of course too large for him and as he was struggling to bring it to bear a well-placed shot caught him in the hip. The Enemy spun violently and went down; the rifle went flying into the grass. Several more shots hit the prone Enemy, stitching holes along the small furry body and punching it down-trail. Sniper down. The center of the line stopped firing and over the course of the next minute so did the anchors; the first attack had been driven back.

After waiting a minute to make sure there were no late charges, Captain Anders said, “We have to retrieve that weapon.”

“It’s just one gun,” Tony pointed out.

“One gun we could use,” the Captain said. “Go get it, Tony. Take Jennifer. We’ll cover you.”

Jennifer took a moment to unclip her equipment belt; she didn’t want her water bag and spare ammo impeding her if she had to move fast. She slid a fresh clip of ammunition into her rifle and handed her half-spent clip to one of the others; it would be refilled and recycled. She met Tony at the center of the line and they moved out quickly. It would take only minutes for the surviving Enemy to regroup, and by now the slower Enemy, the older males and the stronger of the females, would be catching up to the energetic young males. The next attack would be more formidable.

Tony took point while Jennifer covered him from the standard distance; an Enemy-leap plus one meter. They moved cautiously but quickly, covering the forty meters in less than half a minute. They passed right by the body of the Enemy who had first attacked; in death, the meter-tall black and gray creatures looked small and inoffensive, just harmless animals. Jennifer averted her eyes. When they reached the area they thought the rifle had ended up they had to move off the trail and into the waist high twist-grass, any clump of which could be harboring an Enemy.

Her eyes were beginning to sting. Risking a quick glance up-trail, Jennifer saw that there were now several columns of smoke rising from the head of the trail, merging to become a thick black column drifting ominously overhead. It seemed Aram was taking no chances with the living gully.

Tony used his boots to feel around in the grass without taking his eyes off his surroundings. “Got it,” he said, and reached down into the grass. All around them but far enough away that the pair of Last Standers could not make visual contact, Enemy were starting to hoot. Tony pulled the rifle out of the foliage and gave it a quick examination. “The clip’s almost empty, but the stock’s full!” he said with satisfaction. The stock of the gun could hold three replacement clips, each packing fourteen rounds. If the Enemy had not died before exhausting the clip, he probably would have thrown the rifle away as useless afterwards, or used it as a club. The sudden discovery of usable ammunition was a welcome gift from a time when resource production had actually been adequate for their needs.

“Let’s go,” hissed Tony. Jennifer turned to make her way back to the trail, and as she passed by the last frond-plant on the edge of the border between trail and scrub, that’s when she came face-to-face with the Enemy.

It had climbed the frond-plant and was hiding in the hollow where the plant began unfurling its hawser-like stalk into huge star-shaped leaves. It was a juvenile, too small to be a first arriver; it had to be a recent hatchling out on its own. It was curled up in a ball and shaking, terrified by the gunfire and bloodshed. It was black and gray, and had a series of dark spots on its shoulders and a black diamond on the back of its head. Jennifer froze; that diamond shape was intimately familiar to her. She knew that marking well. The Enemy saw Jennifer and tried to hiss at her, but it was a terrified half-effort; no real sound came out.

“Kill it,” said Tony, arriving behind her and catching sight of the animal.

“It’s a diamond,” Jennifer said. “It’s probably not a threat to us.”

“It could breed,” said Tony. He placed the muzzle of his rifle into the hollow and with a single ear-shattering blast reduced the terrified Enemy hatchling to biological samples.

Jennifer fought the bile that rose suddenly in her throat. Jennifer fought the tears which sprang hotly to her eyes. Tony didn’t notice or if he noticed, didn’t care. They made their way back to the defensive emplacement in silence.

There were two larger attacks and several skirmishes over the next several hours, but the Last Standers were never in serious danger. Several weeks of flight had strung their pursuers out over several kilometers, so the Enemy, not patient enough to wait for reinforcements, kept attacking in small and manageable numbers. No more Enemy showed up with rifles, though one showed up with a discharged handgun and stood in the trail clicking it repeatedly at them until Jessie cut him down.

It was almost 1600 hours when Aram Lewitt came hustling down the trail. “About time,” said Anders as the biologist, red-faced and breathing hard, knelt beside him behind a boulder. “Are we ready to move out?”

Aram nodded. “I think it worked. We’re as ready as we’ll get.”

Jennifer wondered what that might mean but then Captain Anders called for suppression fire and retreat. The Last Standers spent half a minute pumping rounds and sound blasts into the foliage down-trail, temporarily scattering the latest grouping of Enemy, then double-timed it back to the head of the trail, with Tony and Jessie rear-guarding their retreat and firing occasional single shots into the bushes.

When Jennifer saw what Aram had done, it made her smile.