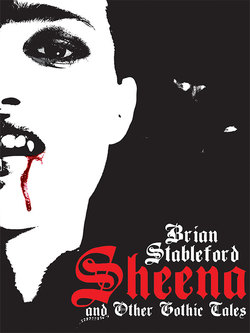

Читать книгу Sheena and Other Gothic Tales - Brian Stableford - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеROSE, CROWNED WITH THORNS

Barbara was the first on my list, because she was the source of my distress. It wasn’t all her fault, of course—how could it be?—but she had been the prime mover in every phase of the unfolding tragedy.

I didn’t have to visit her at home in order to pick up stray hairs from her bathroom; I’d always been a collector and I’d had plenty of reason, over the years, to think that I might one day have need of a little dead Barbie: hair, skin cells, even a little dried blood. I had bits of almost everyone I knew stored in my secret cabinet, along with the tallow, the pins and the needles, and all the other paraphernalia. Going to see her was a different thing; a matter of pride and balance as well as tactics. We’d been rivals and opposites so long that it wouldn’t have been right to do what I intended to do without an actual confrontation, even if it had been possible. I needed to stand face to face with her and look her in the eye, as if I were a sinister reflection lurking in the depths of a darkened mirror, staring out at my bright and gaudy doppelganger in the world of artifice.

She lived, as a Barbie would, in a red-brick house with freshly painted woodwork, on a tidy new ‘model village’ estate south of Marlow, nice and handy for the M4 and the M40. The garage door was aluminum, but it was painted the same shade of burgundy as the window frames. The front door had frosted glass panels and three locks; the burglar alarm was ostentatiously positioned above it and to the left. The door chime sounded like tubular bells.

I watched the expressions flit across her face when she opened the door and saw me there. Surprise, confusion, suspicion and anxiety all showed, briefly, before the professional smile took over and her face reverted to its plastic Barbie mask.

‘R...Rose!’ she said, swallowing her first impulse and calming the exclamation so that it implied pleasure rather than alarm. ‘Why didn’t you call?’

Nowadays, everyone says Why didn’t you call? if you turn up unexpectedly. It’s impolite, these days, to do anything without warning, although that doesn’t stop people doing things in secret.

When I moved forward she stepped reflexively aside to let me in. Inside, the carpets were royal blue and the wallpaper was cream, patterned in silver. Because I hadn’t answered her question she said, ‘You were lucky to catch me in.’ Luck had nothing to do with it; I knew that she was in, and alone—but she was right to be surprised; if I’d turned up at random the chance of finding her in that precious combination of circumstances would have been slim. Whenever her so-called job wasn’t keeping her busy, adultery was.

I went into the sitting room and sat down on a leather-clad armchair. She didn’t know what to do, but she stayed on her feet. ‘Would you like a drink?’ she said, still cruising on automatic. ‘How’s John?’

‘No thanks,’ I replied. ‘You probably know better than I do.’

It took her a moment or two to figure out that the two remarks were unrelated to one another because I’d answered both her questions, in strict chronological order. That was when she sat down, in the armchair that was twin to mine. Rumor has it that people’s faces are supposed to go pale when they find out that they’ve been rumbled by their lovers’ spouses, but Barbie’s didn’t. Plastic never loses its hue, and mischief knows no shame.

‘How long have you known?’ she asked, matter-of-factly.

I nearly said Since it began, but it wouldn’t have been true. Witch or not, I’d had to pick up the usual clues, and my first reaction had been exactly the same as anyone else’s: denial. There was a sense in which I’d known long before it began that Barbara could never be satisfied with what she originally wanted, of course; Barbie had always wanted everything, because she was the kind of person who could. When she’d given John to me—or, as she presumably saw it, had given me to him—she’d always intended to take him back as and when the whim struck her, to fit him in when she found a gap in her life, a window in her schedule. Even so, I’d been taken by surprise when the inevitable finally became manifest.

‘Long enough,’ I said, for want of any better answer.

‘Long enough for what?’ she came back, her poise recovered and her delicate sneer back on line—but I’d rehearsed and she hadn’t; for once I was quick enough to join in.

‘Long enough to decide what to do,’ I told her.

She’d known me long enough not to really see me, even when she looked at me long and hard, but the way her gaze travelled from my boots to my eyes, taking in the whole Stygian ensemble, suggested that she might be making a new appraisal. She probably contemplated making the suggestion that I was certainly dressed for a funeral, but she’d used it too many times before—and what was worse, had heard other people use it. When you always dress entirely in black, it’s the kind of comment everyone stumbles over as they search for something apposite to say; for once, though, it would almost have been appropriate.

‘And what have you decided to do?’ she asked, in a carefully neutral tone. ‘Name me as co-respondent in your divorce petition?’

‘I won’t need a divorce,’ I told her. ‘Nor will you.’

For a moment, she must have toyed with the notion that I was being civilized; I’m sure there was nothing in my tone to suggest otherwise—but she had known me too long. She knew that the last thing I could be accused of was any kind of orthodoxy.

‘Howard wouldn’t divorce me,’ she said, uneasily aware of the probable irrelevance of the remark. ‘We tolerate one another’s little adventures. I’m surprised, in a way, that you and he....’ She trailed off, too nervous to be thoroughly vicious.

‘I think you managed to put him off, when we were all nineteen,’ I said, blandly.

‘Are you sure you don’t want a drink?’ she said, abruptly getting to her feet again. ‘If this is going to be intense, I think I need one.’

‘I’m not staying long,’ I assured her. ‘I just came round to tell you what I’m going to do, so that if it works, you’ll know that it was me. I wouldn’t like you to think that it was just some kind of virus.’

She really did want the drink, but she didn’t want to go over to the cabinet with that kind of tease unresolved.

‘Are you planning to kill us all?’ she said, sharply. ‘Or is it just me? What are you going to do—make a doll that looks like me and stick pins in it?’

‘I don’t have to make a doll that looks like you,’ I told her. ‘For your effigy, I can just buy one off the shelf. I’ll have to mould a photograph to its face, of course, and bind the other identifiers to it with sealing wax, but you’re easy. You’ve always been easy.’

She noticed the double entendre, but her mind was on other matters. ‘Rose, darling,’ she said, mustering all the vitriol she could, ‘I know that this witchcraft stuff has always been more than a pose with you, but surely even you must know that you can’t hurt someone by sticking hatpins in a doll—not even if you call to see them first, to let them know you’re going to do it. It’s all very well for witch doctors in Africa to point the bone at their credulous tribesmen and order them to lie down and die, but it certainly doesn’t work in Marlow.’

‘That,’ I said, patiently, ‘remains to be seen.’

‘Have you tried it before?’ she asked, arching a neatly painted eyebrow.

‘I never had any reason to,’ I told her, not entirely truthfully.

‘I think, darling,’ she said, ‘that you ought to give serious consideration to the possibility that you’re going mad. It’s one thing to be weird, but quite another to....’

This time she broke off because I’d stood up again. She stood too, so that she could look down at me. She was only five foot seven, and she wasn’t wearing heels, but she still had the advantage endways as well as sideways. She took a deep breath, as if to assert that no one with a conventional B-cup had any right to threaten or insult the proud wearer of a C-cup Wonderbra.

‘We’ll see, shall we?’ I said.

‘We’ll see all right,’ she assured me, as I went past her into the hallway. The silver patterns in the wallpaper glistened with obliquely reflected sunlight as I passed them by.

‘Anyhow,’ Barbie called after me, as I reached out both hands to open the security-conscious door, ‘isn’t that sort of thing supposed to rebound on the ill-wisher? You’re supposed to be a white witch, aren’t you?—although you certainly don’t look it.’

‘The question is,’ I told her, before I closed the door on her, ‘what kind of witch are you?’

I had closed the door behind me before she could formulate a reply. I had, after all, had the benefit of my rehearsals.

She was right, of course. The first thing Mrs. Cole told me, when Mum sent me to her to receive instruction in witchcraft, was that the Art should only be used to achieve good ends. ‘Beware of curses, Rose,’ she said. ‘They work, but they always rebound. You never can tell how many people will get hurt, but you’ll always be among them.’

The name on my birth certificate is Rosemary but everybody called me Rose until Barbara Schiff gave me a new nickname—and even Barbie, who was now Mrs. Fletcher, had thought better about using that when she found me on her doorstep while she was in the middle of a red hot affair with my husband.

I didn’t take Mrs. Cole seriously, about curses or anything else. How could I? I was eleven years old and it was 1989. I’d got used to Mum being a witch, having grown up with it, and I’d got used to being included, the way Keith got included in all Dad’s hobbies, but I spent seven hours a day in school and another three watching TV. I couldn’t take any of it seriously. Not that it stopped me doing it, of course. Keith played football and went fishing; I did witchcraft. It was the way things were. Keith learned ball skills and line-casting; I learned recipes and rituals. We did it because it was expected of us. Mum and Dad had divided us up almost from birth, without ever really thinking about it; they’d just taken it for granted that their son would follow in his dad’s footsteps and their daughter in her mum’s. Maybe Mum wouldn’t have been heartbroken if I hadn’t shown willing, but she’d have been disappointed, and if Keith wasn’t going to disappoint Dad then I certainly wasn’t going to disappoint Mum. We weren’t the kind of family that went around disappointing one another more than was strictly necessary.

I never told Mum that I didn’t take it seriously, of course. It was easy to keep the secret. You soon become used to keeping secrets when your mother’s a witch. Not that she was ashamed of it, of course. If anyone brought the subject up, she’d talk about it gladly, explaining with minute care that she was a worshipper of the Mother Goddess, not a Satanist, a healer, not a fortune-teller. It was different for me; most kids can’t be made to see distinctions like those, and would refuse to understand them even if they could. When other kids asked me if it was true that my mother was a witch, I’d say yes but wouldn’t elaborate; if they asked me if I was one too, I’d refuse to talk about it—and I wouldn’t yield to pressure.

When I was sixteen Mum started taking me to the Annual Conference of the Pagan Federation. It was her idea of taking note of the fact that I’d reached the age of consent. We’d sit through all manner of lectures and workshops on rituals and alternative medicine, and I’d listen to it all with saintly patience, waiting for last thing Saturday night, when there’d be a big party with a rock band—usually Inkubus Sukkubus—playing live.

I liked the music; it was the one thing that seemed to me to be worth taking seriously—that and the style that went with it. All the rest, it seemed to the awkwardly shy teenager I then was, was just so much hot air, just like any other kind of religion—including football and fishing.

I never thought of myself as a truly weird kid, but I suppose I must have been, or else I’d never have got into my twenties without ever trying to curse anyone or anything, and without ever finding out that Mrs. Cole was right.

Curses rebound, and you never can tell how many people will get hurt.

I was in my upstairs room, putting the finishing touches to the last figurine, when John arrived home. I had Funeral Nation on the mini-system, playing as loud as the little speakers would allow; he would have timed it better if ‘Graveyard Eyes’ had been playing, but in fact the title track had just given way to ‘Sacred Cities’.

John was late, of course, but not that late. He’d stopped off for a double, or maybe a couple of doubles, at the Rat & Parrot or the Newt & Cucumber or one of the other ghastly newfangled pubs that had sprung up all over the town centre in the mid-90s. He’d probably gulped the booze down in ten seconds flat, with no time to spare for anything more than a nod to anyone he knew; parking and unparking the Peugeot was what had taken up the extra time.

Barbie had phoned him on his mobile, of course. ‘Better get along home, Coldheart,’ she would have told him. ‘Rag Doll’s found us out and flipped. Better calm her down before she goes over the edge.’

If the nickname Barbie had stuck on him had been apt, he wouldn’t have needed the top-up at the Rat & Parrot, or wherever, but it wasn’t warmth he was after in the whisky. I knew he hadn’t had enough—he wouldn’t have dared to have enough, even though the double or two he’d had must have pushed him over the legal limit—and I knew full well that the first thing he’d do when he came stumbling through the door was have another, and another after that.

I was right, of course. He gulped those too before he came up to my room. By the time he arrived in the doorway, aesthetic propriety had been restored; the speakers were booming out the ‘resurrected’ remix of ‘Chaos Mind’.

John had never liked Midnight Configuration; he didn’t mind the poppier goth rock, but he hated anything with guttural vocals and a real edge. ‘Chaos Mind’ wasn’t his sort of thing at all, although at that particular moment in time I couldn’t think of anything that would have suited me better. When he saw that I wasn’t going to switch it off he did it himself, with what was intended to be an angry flourish.

The fact that I’d been to see Barbara had licensed his anger, but it was still a mask for shame and guilt and terror. When he turned towards me from the mini-system he didn’t know whether to yell at me or beg forgiveness, but when he saw the figurines on the desktop the choice became more complicated.

In the end, he could only manage, ‘What the hell are those?’

‘Didn’t Barbie tell you?’ I said, picking up the Barbie doll—one of two that wasn’t entirely my own work. I knew she wouldn’t have; it would have sounded too silly, and she would have known that he’d find out as soon as he confronted me.

I watched his brow furrow, and I knew he was wondering why there were four figurines instead of only two—but all he said was: ‘Well, I can understand why you might want to stick pins in both of us—but it doesn’t mean anything, Rose. It really doesn’t. It needn’t affect you and me. We can get past this, if we can just talk it through. The thing with Barbara’s over—I give you my word.’

By my count, that was four clichés; I had to keep count because I’d promised him a needle for every cliché, starting with the thinnest one and making my way through the packet towards the thickest.

‘It means something to me,’ I said. ‘Even you must have an inkling as to just how much.’ I picked up a big hatpin and held it up alongside the Barbie doll, but it was just for show; I was keeping my real first move in reserve, because I knew it had to be timed exactly right.

‘That’s not going to help,’ he said. ‘Even if it makes you feel better, it’s not going to solve anything.’

‘It’s not supposed to solve anything,’ I told him. ‘It’s supposed to dissolve something.’ All that rehearsal-time was really paying off.

He turned the spare chair around and sat down lumpenly. His face was flushed by confusion and alcohol; he had never seemed less deserving of the nickname Barbie had foisted on him. ‘Hell, Rose,’ he said, ‘we have to be adult about this. I’m sorry it’s happened, but it’s happened. It can’t be undone. We have to get past it.’

That boosted the cliché-count to seven, with one repetition. I decided to forgive him the repetition; it was the only thing I did intend to forgive him.

‘She had no right,’ I told him. ‘It was bad enough that she gave you up, but she could at least have stuck to it. She had no right to take you back. I swore that I wouldn’t let her do that. I couldn’t stop her twisting Howard round her little finger, or throwing me to you like some kind of consolation-prize, but I swore that I wouldn’t let her take you back. I swore that I wouldn’t let her turn the gift into a curse. Curses rebound, you know. Of course you know—even Barbie knows that curses rebound on the sender. Mischief should have stopped her mischief when she wasn’t a Miss any longer—but Barbie doesn’t know how to stop, does she?’

‘It will stop,’ my errant husband said, not following the argument at all. ‘I swear that it will.’

Was that eight clichés in all, I wondered, having momentarily lost track, or seven and two forgivable repetitions? I hadn’t expected him to be quite so prolific. Carefully, I laid the Barbie doll down, on its back. I picked up one of my humble efforts, molded from candle wax.

Its arms and legs weren’t very good, but the photograph of John was neatly sealed to the front of its head. It was clipped from a wedding photograph, of course; that was one cliché I had to count against myself. Not a needle-through-the-belly sort of cliché, but a cliché nevertheless. On the other hand, I had promised myself a whole crown of scathing thorns, so I could still be reckoned to be in credit, cliché-wise.

‘Go ahead,’ he said, bitterly. ‘Stick the pins in, if it’ll make you feel better. I deserve it. If there’s any justice at all, I’ll feel the pain. In fact....’

I couldn’t let him finish. There wasn’t time. I ran the hatpin into the abdomen of the doll, aiming for the stomach, just as the cramps began to hit the real thing.

I had never seen anyone look so astonished in my entire life. I hope I managed to control the grim certainty of my own expression.

‘By my count, John, dear,’ I said, ‘that’s eight clichés and two repetitions. I’ll forgive you the repetitions, but you get a needle for every one of the stupid, shabby, pathetic things you borrowed from the standard script. The hatpin’s for the sin itself.’

He clutched his belly, still unable to believe that the hatpin’s penetration was echoing inside him, unleashing sharp and horrid pain. I showed him the packet of needles, and I showed him which end of the array I intended to start from.

He was still fully occupied by amazement. For the moment, his astonishment was taking the edge off the pain and blocking the fear, but only for the moment.

I took out the thinnest of all the needles, and stuck it into the doll; this time it went in through the side, but the point was still aimed at the stomach.

‘But I don’t believe...,’ he said, and then interrupted himself with a strangled obscenity. He pressed both hands into his booze-softened belly and fell off the chair. If it had been an armchair he’d have been able to stay in it, but I’d never kept armchairs in my room. The one I was sitting on was a swiveling-chair, the kind that some office typists use.

‘It really doesn’t matter what you believe,’ I told him. ‘A witch is a witch regardless. A sin is a sin, and a needle in the eye is a needle in the eye. How do you think I felt? Do you think it would have made one little bit of difference if I hadn’t believed in marriage, or loyalty, or love, or jealousy, or common decency? Do you?’

Needle number two went in, and then needle number three, their points aimed at the small intestine. Coldheart John broke into a cold sweat, and the sweat was pure fear. If he hadn’t believed before, he certainly believed now—if not in marriage, in magic; if not in love, in hate.

‘I’m having a fucking heart attack,’ he moaned, demonstrating his complete ignorance of the relevant warning signs and symptoms as well as a perverse inclination to heed his own fears. ‘Call a fucking ambulance, will you!’

I used my right hand—the one that wasn’t holding John’s effigy—to pluck the receiver from the phone, which lay amid the litter of all my hard labor. I used the forefinger of the same hand to peck out the numbers. It must have been perfectly obvious to John, even in his distressed condition, that I wasn’t dialing 999.

Barbie picked up almost immediately. She must have been waiting by the phone—waiting to hear the news.

I held out the receiver to John, knowing that he could just about reach it if he condescended to remove one of the hands that was clutching at his terrorized stomach.

‘Tell her,’ I commanded him. ‘Tell her what a real witch can do.’

‘You’re crazy,’ he said. His voice was raw and guttural, almost tortured; for the first time in his life he could have sung ‘Graveyard Eyes’ the way it was meant to be sung.

‘I’m not crazy, I’m a witch,’ I told him. ‘And you’d better tell her that while you still can, because you and I have six needles still to go, and you might not be in any fit condition to tell her anything by the time I’ve finished.’

In spite of his agony, he reached out and he took the phone. For the first time in my life, I felt that I was in control, that I had authority. For the first time in my life, I knew that John Coulthart was truly mine. For the first time in my life I was Rosemary for remembrance, and it all seemed to be worth it, even though I knew that I’d end up as mere Rose, crowned with thorns.

‘Tell her!’ I said—and he actually screamed.

I don’t know why we had to have nicknames, or how it came about that they got assigned when they did. I suppose it was a kind of bonding—the sort of thing young people do when they’re hurled out of the family nest into a world where relationships have to be made instead of found.

Because I was a year older than Keith, I was the first to go away, although I’d never really thought about it as going until I was actually gone. Applying to university had just been the next expected step—expected even by Mum, although she knew full well that you couldn’t study witchcraft at any British university. She’d never tried to encourage me to study one subject rather than another at school, obviously figuring that the instruction from Mrs. Cole and our dutiful association with the Pagan Federation would supplement any kind of orthodox education as well as any other. If Mum was relieved that I clung hard to English Literature and refused to interest myself in science she never showed it. If she was desolate when she and Dad unloaded my stuff outside the hall of residence where I’d been allocated a room she didn’t show that either. Every week, though, she’d send me a brand new phonecard, to ease the ritual of keeping in touch.

I don’t know how exactly how it came about that I became a part of a little group of four. It wasn’t entirely a matter of chance, and it certainly wasn’t entirely a matter of convenience. I suppose, looking back, that it was because I liked Howard Fletcher that I gravitated into his orbit, and because Howard knew John Coulthart from school that he turned out to be already occupying the next orbit in—and it was probably because John thought that Barbara Schiff looked gorgeous that he tried with all his might to bring her into our combined gravitational field. Once we were together, though, that initial chain of causation gave way to a much more complicated combination of attractions and movements.

Howard’s nickname must have been left over from school. John had obviously been calling him ‘Flasher’ for years, and wasn’t about to be put off just because Howard wanted to make a clean start—quite the reverse, in fact. I don’t think Howard ever retaliated in kind; it was certainly Barbara who first started calling him ‘Coldheart’, deliberately echoing the kind of transformation that he insisted on wreaking upon his friend’s name. I didn’t want to get involved—I never called Howard ‘Flasher’—but they wouldn’t leave me out of it. I even explained to them that Rose already was a nickname, because my name was actually Rosemary, but they wouldn’t be content with that.

‘We could call you Ophelia,’ John said, after I’d told him what my full name was, ‘because Rosemary’s for remembrance.’

‘She’s not Rosemary now,’ Howard pointed out. ‘She’s Rose.’

‘But she has no thorns,’ John said, still trying to be clever, ‘and a Rose by any other name would smell as sweet. If only Ophelia hadn’t gone mad....’

It was Barbara who took the next step. Like any new girl, not knowing what to expect, I’d come to university liberally equipped with notebooks and files, all neat and new and far more brightly-colored than anything I ever wore, and I’d punctiliously stenciled my name on every one of them, in formal capitals: R. EDGELL.

‘Rag doll,’ said Barbara. ‘They called her Rag Doll.’ She was quoting an old song by the Four Seasons, that must have been her mother’s or her grandmother’s vintage. She’d never even heard of Inkubus Sukkubus or Midnight Configuration or All Living Fear, or any of the bands I liked. Not many people had—which was one of the reasons I liked them so much.

Maybe she wasn’t being vicious, at least not consciously. Maybe she was just looking to apply the same methodology to my name as she’d applied to ‘Coldheart’ John’s. She certainly didn’t have any good reason to attack my clothes, which were no worse than hers. I was used to people remarking on the fact that they were uniformly black, but no one had ever criticized their quality.

Perhaps, if I’d been quick enough, I could have derailed the entire train of thought. Perhaps, if I’d only known how, I could not only have kept myself in their minds as Rose but made her Barb or Barbie in our everyday usage—but the suggestion was rejected on the grounds that the contractions were too obvious, and too commonplace to qualify as a private joke. I suppose it must have been John who took up the baton and dubbed her ‘Mischief’—on account, of course, of the fact that her surname was Schiff and she was, for the moment, single.

‘Mischief’s no good,’ I pointed out. ‘It won’t make sense after she gets married.’

‘Nor will Rag Doll,’ Barbara was quick to point out. ‘But that won’t matter. When you marry John, you can be Mrs. Coldheart.’

She only said it to make mischief, of course. She only said it because she knew full well that it was Howard I liked. It was the first inkling I’d had that she liked him too—and that she had already considered, as coolly as you please, the possibility that if John’s obvious desire for her might be deflected, I was the direction in which he ought to be encouraged to look.

Even if the nickname itself hadn’t been a kind of curse, that supplementary remark certainly was—and like all the worst curses, it unwound over time, rebounding as it went, and it kept on and on rebounding.

‘It wouldn’t be as bad as Mrs. Flasher,’ John contended, but even I could see that it all depended how flash she was to start with—and Barbie was very flash indeed. Not that beautiful, and not that rich, but certainly flash. She thought she could have everything she wanted, and she would probably have been right, if she hadn’t tangled with a witch. We were tangled already, of course, but only by common-or-garden friendship. It wasn’t until the business of the nicknames that the tangles became thorny, catching like curses. Until then, it hadn’t mattered that I was a witch, but afterwards....

I didn’t swear anything there and then, but that was when it all began in earnest. John had been right about my having no thorns. Until then, in spite of my being Rose instead of Rosemary, I’d been entirely innocent of thorns. From that moment on, though, I was fated to be crowned with them.

Howard arrived at half past eleven. If he’d only had to drive from Marlow it wouldn’t have taken him nearly as long, but he hadn’t been at home. Lately, he’d been spending a lot of time away from home, exactly as John had, and probably for much the same reason: fucking someone else’s Barbie while his own got fucked in her turn. No witchcraft involved, of course: no love potions, no real glamour. Just the everyday routines of ordinary folk, supposedly hurting no one. But a needle in the eye is a needle in the eye, and you feel what you feel, even when the needle isn’t literal, especially if you’re a witch.

Flasher Fletcher rang the doorbell in an uncommonly assertive manner, although I didn’t take more time than was warranted letting him in.

‘Hello Howard,’ I said. ‘Would you like a drink?’

‘Where’s John?’ he demanded. He was already looking up the stairs, wondering if he ought to bound up them two at a time and hurl back the door of the room I had claimed as a counterpart to John’s ‘study’: the room in which I kept my cabinet, and my recipes, and my pathetic apology for a sewing kit.

‘Why?’ I asked, innocently. ‘Do you want to beat the living daylights out of him for fucking your wife?’ My assiduous rehearsals were still paying dividends.

Howard cast one last look up the staircase, and then turned to look down at me. He looked down from a much greater elevation than Barbie, greater even than John. From way up there I must have looked very tiny indeed, and utterly harmless. I must have looked meek, too, because he relaxed perceptibly.

‘You’ll never believe this, Rose,’ he said, perhaps hoping that it might even be true, ‘but Barbara’s got some stupid idea into her head that you might have killed him. She only insisted that I came round to make sure that he was all right.’

‘Only insisted,’ I echoed. ‘That doesn’t sound like Barbie at all. She was never one to take things one at a time.’

‘She said that you were pretty pissed,’ Howard said, blundering on regardless. ‘I can understand that, of course. I mean, I was exceedingly pissed myself when she told me what had happened. It’s not the first time she’s got off with one of my mates, but I would have thought that John, of all people, was way out of bounds. You’re supposed to be her best friend, for Christ’s sake! And what on Earth could he be thinking of? It’s one in the eye for us both—but we do have to be adult about these things, don’t we?’

There was a tiny hint of self-congratulation in his voice, born of the tacit assertion that he wasn’t the kind of guy who would go around fucking his best friend’s wife. In all the years I’d known him, I’d never once heard Howard the Flasher say ‘There, but for the grace of God, go I.’ It was difficult to understand, at that particular moment, why I’d ever been besotted with him.

Then he smiled, and I remembered.

‘I know you better than Barbara does,’ he said, mistakenly. ‘I know you’re tougher than you look, and smarter than any of us. You wanted to throw a scare into her, didn’t you? It was something you and John cooked up together, wasn’t it?’

I smiled too. ‘I wanted to throw a scare into her all right,’ I said. ‘And you’re absolutely right—it was something I cooked up, with John in mind. Are you sure you don’t want that drink?’

‘I knew it,’ he said. ‘I knew you couldn’t really be sitting upstairs sticking pins and needles into voodoo dolls. I knew it had to be a joke—like all that awful music you like so much.’

He laughed. That was Howard all over; whenever he was in doubt, he laughed. The first time he’d found out about his wife’s little adventures he’d probably had to choke back a tear or two, but in the end, he would have decided to laugh about it. He would have pursed his lips, gritted his teeth, and matched her adventure for adventure, so that they could both laugh at life’s little ironies, and congratulate one another on how civilized they were.

I had to put a stop to that train of thought, or I’d have merited far too many thorns to fit into any mere crown. I’d already opened the door to the sitting room and I was standing there like some midget butler, trying to usher him through. ‘Drink?’ I said, again. Men are like dogs; if you reduce communication to one-word sentences and repeat them often enough they usually get the message eventually.

‘Well, OK,’ he said. ‘Just one—I’m driving. Bloody Mary, if that’s OK.’ His BMW was bigger than John’s Peugeot, but he had two more points on his license. He’d never have sunk two doubles in the Rat & Parrot or the Newt & Cucumber and then got back behind the wheel.

When he sat down on the settee, though, the Flasher looked around yet again, furtively. ‘Where is John?’ he asked.

‘Oh, he’s already gone,’ I said. ‘Barbie knew that, of course. If I had to guess, I’d say that she probably only sent you round here in the hope that I’d beg you to fuck my brains out, so that I’d lose the moral high ground in this business between John and her. I think she’d prefer me to get even in the ordinary way, rather than stick her effigy into a candle flame and watch it burn. Well, she would, wouldn’t she?’

I handed him the Bloody Mary; I knew that Howard never drank whisky, so I’d already poured the stuff in the doctored bottle down the sink. He looked at me in complete confusion, although I thought I’d detected a faint hopeful gleam in his eye when I mentioned the possibility of his fucking my brains out. Flashers are always teed up to respond to sweet nothings of that kind.

‘I always loved that dry sense of humor,’ he said. ‘It drives Barb crazy, though. I really am sorry, you know—about her and John. I can take it, but I know how cut up you must be. If I’d known...I really am sorry. She is too, you know. She just didn’t think....’

‘If you were John,’ I informed him, ‘I’d owe you half a dozen needles by now—and I only have the thicker ones left. But you’re not John, are you? You were never that cold-hearted.’

He laughed again, in a curiously dutiful fashion, even though he didn’t have a clue what the remark about the needles signified.

‘Come upstairs,’ I said to him, opening the door again. ‘There’s something I want to show you.’

The gleam came back into his eye, flashing at me as he turned his head. He honestly thought I meant the bed. He honestly thought that if I really believed that Barbara had sent him around to give me a chance to even the score, I might have given her the satisfaction of taking the bait. He didn’t know me at all, and never had.

I suppose I would have wondered again what I could ever have seen in him, if he hadn’t already been flashing his smile

I’d hung around with girls prettier than myself long before I met Barbara Schiff, of course. At school, I’d gone with better-looking acquaintances to discos—even to gigs when the rare opportunity presented itself to see one of my favourite bands outside the hallowed environs of the Pagan Federation Conference. I knew well enough how such things worked: how predatory boys hunted in pairs, eyeing up their paired targets with assumed expertise, mouthing the usual clichés like the oldest rituals in the grimoire: Don’t fancy yours much. You take the little one; I’ll handle the Wonderbra. You take the thin one—she won’t need as much oiling. In my teens, though, that sort of thing had all been safely confined to the odd evening out, after which—no matter what might develop or how far things might go—everybody went home.

With Howard and John and Barbara it was different; we already were home. We lived on the same corridor, shared the same kitchen. John and I even attended the same lectures—but Howard was a historian and Barbara, thinking herself more fashionable by far than the rest of us, was doing Media Studies.

Left to ourselves, Coldheart John and I would probably have kept our distance from one another, or collided once and moved apart, never pausing overlong thereafter as our paths criss-crossed—but we weren’t left to ourselves. We were part of something larger and more complicated. We were entangled, by Flasher’s flair and animal magnetism, by Mischief’s leadership and Machiavellian scheming.

When Mischief decided that she must have Flasher she also decided that Rag Doll, whose initial attraction had been to him, must be fobbed off with Coldheart, whose initial attraction had been to her, thus neutralizing both potential inconveniences. It was probably unnecessary, and could easily have proved pointless, but that was the way she saw it. Once the precedent had been set, she returned time and time again to that same formularistic curse: ‘When you marry Coldheart’.

Never once did Barbie say, ‘When I marry Flasher’, but she never needed to. All she needed to do was to repeat her own spell over and over, until the people around her began to take it for granted. I never did, of course, but I was a witch and had been trained to know witchcraft when I saw it, even when it was being used by someone who would have laughed her socks off at the thought of the Pagan Federation’s Annual Conference. John and Howard had no idea, any more than Dad or Keith would have done. They accepted the assumption without ever realizing that they were being bound by a spell. By slow degrees, as our first year progressed, we stopped being a quartet and became two pairs.

Maybe, if I’d cast a counter spell soon enough, I could have turned the thing around—but I didn’t have Barbie’s advantages. I’d had a lifetime of knowing what to look for, but I’d never been able to take any of it seriously. She’d had a lifetime of blissful ignorance, and was able to take what she was doing very seriously indeed because she thought of it as common sense instead of magic, as everyday lust instead of demonic possession, as playing with words instead of laying curses.

If I’d been able to tell my mother, she would probably have helped me out. If Mrs. Cole hadn’t ‘passed over’, I could have consulted her, but she had gone to sleep in the bosom of the Goddess three years after I’d started secondary school. All I had to console me was my music: Corpus Delicti and All Living Fear, Ataraxia and Midnight Configuration, Faith and the Muse and Faith and Disease.

I should have fought back, but I didn’t. All I could do, then, was to swear that if Mischief ever took back what she had given, running needles into my eyes to start my bitter tears, then I would make her suffer in return—even though I knew that any curse I laid would hurt me too.

It didn’t seem appropriate to change the record, so I put ‘Funeral Nation’ on again while I showed Howard the two dolls I’d adapted and the two dolls I’d made. He tried to laugh, but ‘Subterrania’ was already pounding in his ears, and he couldn’t quite manage it.

‘Barbie wasn’t making it up,’ I told him, ‘and she wasn’t being stupid, although I’m sure you must have told her that she was. When she heard John screaming, he really was screaming—and when he left, he didn’t go to the hospital, because he was utterly and absolutely convinced, by that time, that he had to do exactly what I told him to do. He went to Barbie’s. He’s there now. By now, he must have been screaming and moaning at her for the best part of an hour, as well as vomiting all over her royal blue carpet and shitting his pants. He won’t die, of course, but he doesn’t know that—and neither does she.’

‘Sinister Sinister’ was booming from the speakers, and even Howard had the grace to be more than a little bit frightened.

‘What have you done, Rose?’ he asked me, in a tone that suggested that all thought of fucking my brains out had vanished from his fickle head.

‘Exactly what you said—I cooked something up, from one of Mummy’s old recipe books. Not exactly eye of newt and toe of frog but something not dissimilar. Natural selection has devised all manner of tasty trifles for the benefit of innocuous creatures that need a little something to discourage all the predators who might otherwise make a meal of them. Not fatal, of course—the whole point of such devices is that the predators need to learn from bitter experience. Rumor has it that mixing the brew with the alcohol increases the intensity of the spasms, but I’ve never actually experimented with it before.

Howard the Flasher looked down, horror-stricken, at the empty glass clutched in his hand. I let him stew for three or four seconds by saying: ‘I put it in John’s whisky—the vodka’s just for guests, and it’s as pure as the day it left Warrington.’

‘I don’t understand,’ he said, truthfully.

‘That’s good,’ I assured him. ‘Because this is where we move into unknown territory. By now, you see, Barbara must be just as confused as you are. She still doesn’t believe, of course, but it’s not what you believe that counts: it’s what you feel. Barbara’s heart was always a few degrees colder than John’s, but even she can’t be ice-cool right now. Not with John groaning like a sinner in hell in front of her, and with all the anxiety and shame and guilt and everything else that goes with the territory. No matter how civilized you and she may think you are, the sickness must already be creeping upon her. All it needs is one last twist.’ While I was talking I picked up the phone, hit REDIAL and handed the receiver to Howard.

He took it.

‘Now, Howard darling,’ I said, as sweet as sweet could be, ‘I want you to do exactly as I tell you to. When Barbie answers, tell her who you are and where you are—and then describe, as neatly and as accurately as you can, exactly what I’m doing.’

I picked up the Barbie doll, and I drew out the next needle from the pack. Only the thicker ones were left, but there were plenty of them.

Howard looked at me as if I were mad—but only for a second. Then he saw the logic of it.

He could have refused, of course. Barbie was, after all, his wife, and they were both civilized people, who tolerated one another’s little adventures. As I’d already told him, though, it doesn’t really matter what you believe; what matters is how you feel. He had a bitter taste in his own mouth, which hadn’t come from the Bloody Mary, and it was his royal blue carpet too.

‘Barbara,’ he said, ‘it’s me. I’m in Rose’s upstairs room. She has a Barbie doll in her left hand, which has a photograph of you mounted on its face, and a needle in her right hand. Now she’s resting the point of the needle on the doll’s stomach, and....’

He had the tone of voice exactly right, but he wasn’t entitled to any credit for that. For the moment, just like his effigy, he was all my own work.

When Howard had finished I took the receiver back and replaced it in its cradle. I didn’t bother to listen to the strangled sounds that were coming from the other end. I knew that the power of suggestion had done its work, and done it well.

I picked up the figurine that had Howard’s face and passed it over to him; he took it meekly.

‘It’s up to you to keep it safe, Howard,’ I told him. ‘For as long as it exists, it’s the only image of you that has any power. If you look after it, no witch will ever be able to do you harm—but if you break it, or allow it to become distressed, you’ll suffer. Whether you believe in it or not, you’ll suffer. Do you understand that?’

He nodded, like a child confronted with the earnest admonition of a trusted parent. Later, no doubt, he’d tell himself that he’d been foolish, and that of course the makeshift doll had no power to harm him—but he’d keep it safe anyway. He wouldn’t dare to test the proposition by running a needle through the effigy’s waxen flesh, or breaking it in two, because he’d figure that it was best to be on the safe side.

Howard was the kind of man who always figured that it was best to be on the safe side. He’d married Barbara Schiff instead of somebody capable of loving him, but even that, in its way, was a matter of being on the safe side.

‘You’d better go now,’ I told him. ‘They might need an ambulance, and they might not have the guts to call for one themselves.’

I wasn’t absolutely sure, at that particular moment, whether the suggestion I’d planted might even be powerful enough to destroy them. I’d demonstrated to Barbie that Marlow wasn’t quite as far from the dark heart of Africa as she had assumed, and even I couldn’t be sure how much margin there really was.

Howard got up to go, carrying the figurine as if it were the most precious thing he owned.

If only I’d had such confidence in my art at nineteen, I thought, the whole farce might have been unnecessary. If only I’d had the courage and the imagination, I might have spoiled Barbie’s spell and claimed Howard for myself. As I heard the front door close behind him, though, I wondered whether the situation might not have reproduced itself anyway, with Flasher Fletcher as the errant husband of poor Rag Doll and Coldheart Coulthart as the hapless Mister Mischief.

Reflexively, I reached out to hit the PLAY button on the mini-system, starting Funeral Nation yet again. It was playing far too loudly for that hour of the night, but I needed the oppressive rhythm and the dark sentiment of the words. I had no rhymes of my own to serve as incantations, so I had to borrow some.

I picked up the last of the four dolls: the rag doll to which I’d attached my own photograph, about whose neck I’d placed a noose woven from my own black-dyed hairs. Then I opened a little plastic box of dressmaker’s pins: the kind that have little colored spheres in place of flat no-nonsense heads.

I began to take pins from the box, one by one; I pushed them into the head of the doll, so that the colored spheres marked out the arc of a halo. As I pushed them in I exerted every atom of my will to the magical task in hand. I commanded the points of those pins to delve into the depths of my own tortured mind, to kill the terrible thoughts and cauterize the horrid feelings, and give me the strength not to care.

I wouldn’t have minded paying a price for what I wanted, in ordinary pain. Any pure and simple headache would have been preferable to the kind of hurt I actually felt: the hurt compounded out of raging jealousy, the sense of my betrayal and the awful awareness of my own implicit worthlessness. I was perfectly prepared to wear a crown of thorns, and to endure its pricking, provided that I could be free of ire and guilt and dreadful self-pity.

But it didn’t work.

Witchcraft had worked on John, with a little help from one of Mum’s grimoires, and it had worked on Barbara, with a little help from John’s awful example, and it had worked on Howard, with a little help from my own dark intensity, but it still wouldn’t work on me.

I just couldn’t take it seriously.

In spite of my newfound power, my proven authority, I simply couldn’t take it seriously.

That was the manner in which my curse rebounded on me—or, at least, the manner in which it began its rebounding. I don’t believe that the crown of thorns actually intensified or prolonged my misery, but that’s not the point. The point was that hurting John and Barbara—and showing them that I had the power to hurt them—didn’t make me feel the least bit better. It simply didn’t help

John was discharged from hospital two days later, having made a complete recovery. He didn’t tell the doctors there the truth about what had happened to him; he just kept on assuring them that it must have been something he ate. Barbara was released the following day, having steadfastly made the same assurances. If the doctors knew or thought differently, they made no public declaration of the fact; all that mattered to them, it seemed, was that their patients had got better.

John came home to pack his things, and then left again. Barbara went home with Howard, and they resumed their lives, sensibly putting the incident behind them. I stayed where I was, alone.

And so the curse unwound, and kept on unwinding.

I threw the effigies of John and Barbara away, with all the needles sticking in them. They were only dolls, and only needles. The last needles I’d inserted—the ones I’d stuck into the dolls’ eyes—had only deprived Coldheart and Mischief of the ability to see clearly enough to repent what they had done. I hung on to my own doll, as Howard presumably hung on to his, but I couldn’t keep it safe.

I still look at it occasionally, and reflect on the foolishness that inspired its ridiculous crown of thorns. Sometimes, I’m a little rough with it. I just can’t seem to help myself.

Unlike Barbies, rag dolls come apart at the seams.