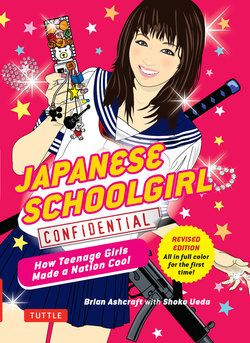

Читать книгу Japanese Schoolgirl Confidential - Brian Ashcraft - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIf clothes make the man, uniforms make the schoolgirl. Whether it’s those sailor suits with big red ribbons, blue blazers with striped neckties, or short plaid skirts and loose socks, the Japanese schoolgirl uniform is more than a wearable ID. It’s a statement. With roughly 95 percent of high schools in Japan requiring them, wearing uniforms (seifuku) is not simply the norm, but a rite of passage, representing that carefree period in a woman’s life when she makes the transition from child to adult.

It wasn’t always this way. At the Tombow Uniform Museum in Okayama, costumed mannequins are displayed in a timeline revealing the evolution of uniforms. The museum is Japan’s only academic garb repository and sits catty-corner to Tombow’s school uniform factory, where threads are fabricated for students across the country. Okayama is the uniform capital of Japan, and if you’re wearing a Japanese school uniform right now, there’s a seven out of ten chance it’s from there.

The groundwork for mandated clothing in Japan was laid in the seventh and eighth centuries, when Korean- and Chinese-influenced imperial decrees compelled the classes to wear certain types of clothes. During the Heian Period (794–1185 ad), idle aristocrats were obsessed with seemingly trivial wardrobe matters like wearing the correct colored sleeves. When your days aren’t spent toiling in a rice paddy, even the most minor fashion detail is important!

By the Edo Period (1600–1868), regular kids could study calligraphy, poetry, and Buddhism at their local temples. In a glass case at the Tombow museum, two smiling life-sized dolls are dressed in their regal study kimonos: one sits on the floor, and the other stands, grinning ear-to-ear. These “study clothes” were threads donned for learning, but not strictly enforced or even uniform per se. For something to truly be a “uniform” it needs to be exactly the same, and that wouldn’t happen to Japanese school clothes until the late nineteenth century.

Hello sailor!

FOLLOWING THE OPENING OF JAPAN in 1853 by the “Black Ships” of the US Navy, large numbers of foreign experts in a myriad of fields and industries were brought in to dispense their knowledge. Western fashion also began to be adopted, and leading the charge was the Meiji Emperor who posed for photographs in French-inspired military garb, complete with a sash, fringed epaulettes, and a breast full of medals.

COURTESY UEDA FAMILY

France and the US served as influences for the new educational code of 1872, which established a national school system and made education compulsory. By the end of the decade, male students at the newly established Gakushuin University were sporting navy-colored school uniforms called tsume-eri (high collar), or gakuran (which loosely translates into “Western uniform”). The high collar design covered the neck, making students hold their heads higher and giving the young men a stronger appearance.

The following decade at Tokyo University, tsume-eri with spiffy golden buttons instead of simple black hooks were introduced. While not a military uniform, the tsume-eri certainly had a whiff of the armed forces the Meiji government was ramping up—most notably the Navy, the service adored by the nation’s kids. According to Katsuhiko Sano, director of the Tombow Uniform Museum, the reason the Navy seemed so romantic was because sailors went overseas and had an international world view (while civilians could face the penalty of death for traveling overseas). “Boys’ school uniforms started from that desire to emulate naval heroes.”

THE ROYAL COLLECTION © 2010, HER MAJEST Y QUEEN ELIZABETH II.

At the Tombow museum hangs a copy of an iconic 1846 portrait of the then Prince of Wales, Albert Edward. The future King of England looks about four years old and is decked out in a miniaturized sailor suit that looks uncannily like what Japanese schoolgirls wear today. The painting caused a sensation in Britain at the time. In an age when blue-bloods set fashion trends, soon children across the UK were suited up in sailor outfits. By the tail end of that century they were also the de facto threads for American and European kids. The nautical theme even spread to adult attire with seaside summer holidays very much in vogue.

During the Meiji Period (1868–1912), as Japan suddenly found itself playing catch up with the West, it began importing loads of foreign concepts, fashions, and technology, including the latest in military firepower. The military was short hand for modernization since Japan needed a modern military to become a modern power. Along with that came new uniforms, including European style naval outfits. Pretty soon boys in Japan were required to wear school uniforms inspired by the navy look. Girls, however, still wore kimono. But the snug, form-fitting kimono, while fetching, were designed for sitting on tatami mats—not in a chair hunkered over a desk, taking notes, and listening to a teacher. A change was needed. Some educators suggested the hakama, which were pants designed for horseback riding and worn by, gasp, men. Others, more forward thinking, proposed Western-style uniforms. That pitch was nipped right in the bud when the country’s first Minister of Education—a British-educated advocate of Western clothing and culture—was assassinated in 1889. Worried that schoolgirls would be targeted for wearing Occidental outfits, a compromise was reached: young ladies would don balloon-like Japanese trousers. They looked like feminine skirts, but offered pant-like functionality.

That would change at the turn of the century when educator Akuri Inokuchi was sent abroad to research physical education at Smith College in Massachusetts. There she saw female students doing exercises in sailor-inspired “bloomers.” When she returned to Japan in 1903, Inokuchi encouraged school-girls to get off their duffs and do gymnastics, and to do them while wearing the sailor-style outfits she had seen in the US. This was less to do with fashion and more to do with practicality as the bloomers allowed women to move freely. Two years later, after students at the country’s national high school for girls began daily exercises in similar clothes, the look began to cling. Sailor outfits became synonymous with active wear, but it was not until the next generation of schoolgirls that the now iconic sailor uniform was born.

Standing beside a display in the Tombow museum, Katsuhiko Sano points to a black and white photo from 1920, showing a schoolgirl in a long naval gown. “This is the first sailor-style school uniform for girls,” he says. Sano should know. He not only tracked down that uniform, but also created the Tombow Uniform Museum to show how far uniforms have come. Thanks to Sano’s detective work, Tombow was able to pinpoint this uniform from Heian Girls’ School in Kyoto as the country’s first. Unlike other school outfits or study clothes, these sailor-style, one-piece dresses were all identical and worn in class. But the one-piece design never really caught on.

HEIAN JOGAKUIN UNIVERSITY

In 1915, the headmistress of the Fukuoka Jo Gakuin—a Christian High School for Girls—was Elizabeth Lee, an American. “Ms. Lee was very beautiful,” says Sano, “and all the students loved her fashionable sailor-style clothes and wanted to dress like her.” The kimonos the girls had weren’t exactly practical for study or physical education. A local tailor, Ota’s Western Clothing Shop, began reproducing Lee’s outfits for the spring 1922 class, complete with a ravishing beret. The Ota design made the rounds at other missionary schools, and in the pre-war era, the two-piece sailor suit became synonymous with Christian education. Best of all, the naval look of girl’s uniforms dovetailed thematically with the naval inspired boy’s uniforms. The two-piece design with a separate blouse and skirt became the blueprint for sailor uniforms and the design still used by learning institutions across Japan.

FUKUOKA JOGAKUIN JR & SR HIGH SCHOOL

Meanwhile, in Okayama, the Tombow factory was producing split-toed socks called tabi, but having a hard time staying afloat. “Fewer and fewer people were wearing traditional Japanese clothes on a daily basis,” explains Sano. The company needed another product and ended up ditching the socks to switch to school clothes. It was 1930—a time when it was common for families to have as many as five or six children—and the government was pushing education. Voila! Instant customers.

FUKUOKA JOGAKUIN JR & SR HIGH SCHOOL

In the years leading up to World War II Japanese nationalism raged. Yet schoolgirls still wore Western sailor suits. (Though, when materials became scarce during the war, schoolgirls wore uniforms fashioned out of their mothers’ old kimonos). Pants, however, replaced the skirts, with the rationale that it was easier to run from falling American bombs. Detachable padded hoods to protect against flying shrapnel were also necessary.

FOX PHOTOS/HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

The war did little to stop the advance of the sailor suit as Japan got back on its feet in the post-war years, and it became part of the academic landscape. Other changes in the social fabric also had little effect on their spread. In the 1960s Japan experienced anti-war protests and leftist demonstrations much like those in the US and Europe. School uniforms were viewed as a symbol of Imperial Japan and came under fire by some on the grounds that they stripped kids of their identity and creativity. For baby-boom teenagers the in-thing was the “Ivy” look, and they dressed like characters out of a J.D. Salinger novel, prepping themselves up with chino pants, sweater vests, and button-down shirts. “Everyone thought being free was ideal during the 1960s,” says Sano. “Uniforms came to represent the oppression of freedom and were therefore looked down upon.” This stink might have caused some schools to rethink the mandated school outfits, but hardly stubbed them out.

TOMBOW UNIFORM MUSEUM

In the confining parameters of school uniforms, however, kids were figuring out their own ways to show their individuality—with scissors! In the late 1960s and early 70s, bad schoolgirls in long skirts and Converse sneakers began cutting sailor tops short, exposing bare midriffs. The look was called sukeban explains Sano—slang for “girl gang leader.” Not all sukeban chicks got in fist fights and knocked heads with baseball bats, but the delinquent look became iconic. The mere act of standing up to conformity by altering assigned clothing gave the most innocuous suburban rebel the air of danger.

Sukeban style marked the nascent stages of “uniform fashion” and soon schoolgirls everywhere were personalizing their apparel. While the first sukeban did the uniform altering themselves (or had their mothers do it), tailors soon began charging to shorten school tops. And when sukeban graduated, they’d embroider things like roses and Japanese kanji characters on the back of their sailor suits. Nothing says thorny rose like a schoolgirl who’s going to punch your face in—or at least act like she will.

Sukeban boy

YAKKUN SAKURAZUKA not only knows what it’s like to wear a schoolboy uniform, but just how comfortable a form-fitting schoolgirl uniform can be. Since getting into showbiz over ten years ago, the cross-dressing Yakkun has donned a sailor suit as part of his act. And not just any sailor suit but a hard-hitting sukeban version.

TOP COAT CO., LTD.

“I chose a sukeban style uniform,” he says, “because I didn’t want to be a weak, effeminate character, and the tough sukeban style was the farthest thing from that.” Fitting for a tough guy-girl comedian who wields a wooden kendo stick and heckles his audience with biting barbs. But he’s got a soft side too: “I love it when I’m confused for a girl, or when a woman says I’m pretty.”

In true sukeban style, Yakkun wears a long skirt and bare midriff with exposed belly button. “It’s certainly made me more self-conscious about developing love handles.” The first time he put on the sukeban sailor uniform, he was impressed how easy it was to move in the outfit. Still, the look took getting used to. “I kept stepping on my skirt when I was going up and down the stairs,” he says.

Yakkun’s collection consists of six outfits: two light summer uniforms, two heavy winter uniforms, one checked patterned uniform, and one white embroidered uniform. Some are order-made, some were presents from fans. “The best thing is that I don’t need a wardrobe stylist,” he says. “The worst thing is that the uniforms show dirt easily.”

But the biggest difference between wearing girls’ and boys’ school duds is, according to Yakkun, the protection: “The male uniform isn’t drafty during the winter.”

Yakkun Sakurazuka, whose real name was Yasuo Saito, was tragically killed after being hit by a car on October 5, 2013. May he rest in peace.

By the 1980s, baby boomers who’d grown up when uniforms were frowned upon had children of their own, and when it came time to get the kids some learning, preppy school clothes proved very popular. School dress was conservative, and the sailor-suit standard found a new rival: the blazer.

TOMBOW UNIFORM MUSEUM

Sport coats had been part of some school uniforms for decades, but it was in the mid-1980s that the blazer really took off. More than the “look,” the practicality of the blazer and skirt drove its appeal. Students typically only bought a couple of sets of uniforms for all of junior high or high school. So for the first couple of years these may have been too big, but when girls hit a growth spurt the outfit would look terrific. In the final years of school, however, the uniform would be bursting at the seams. A blazer layered with a white shirt and a sweater vest was much more forgiving to raging teen hormones.

The preppy single-breasted jacket became very much in vogue—Tokyo schools leading the charge with navy and caramel colored versions. Large school crests sewn onto the blazers not only appealed to parents’ preppy sensibilities, but breathed an air of nostalgia as the style was reminiscent of the jackets-with-embroidered-crests worn by the athletes of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. In the “bubble” economy of 1980s Japan, the uniform moved well beyond simply functioning as a uniform—it became brand-name fashion.

Schools noticed a sudden spike in applicants when they changed their uniform designs. As a result, institutions across the country began adopting new styles. People like illustrator Nobuyuki Mori began to take a keen interest in the sudden variety of uniforms springing up at the time. While still in high school, Mori began sketching school uniforms in his neighborhood to quiz his buddies. When he left the ’burbs to study for university entrance exams in Tokyo, the endless uniform variations blew his mind. He noticed that no two uniforms were the same. They couldn’t be, or else they’d cause confusion. So Mori set out to catalogue all this in the ultimate compendium, his 1985 book, The Illustrated Schoolgirl Uniform Guidebook, which would go on to sell two hundred thousand copies. “I was inspired,” says Mori, “by all the different and beautiful uniforms in Tokyo.”

NOBUYUKI MORI

But anyone who tried to keep up to date with uniform trends had a huge job on their hands. By the mid-1990s, preppy was out, and slutty was in. Schoolgirl skirts got short and white socks got loose. Much like the sukeban a generation earlier, girls rebelled against strict school uniforms. They wore outrageous makeup, dyed their hair, got fake tans, and rolled up their skirt’s waistband to turn long dresses into D.I.Y. micro-minis. These dangerously short skirt–wearing, golden brown tanned schoolgirls were called kogal or just gyaru.

When girls began showing skin at more conservative institutions, parents and teachers gasped, and strict schools started scrutinizing scanty hemlines with before-class spot checks. Some private academies even went so far to have teachers scattered off-campus to eyeball girls on the way to school. Japanese students all carry rule books that outline their school’s regulations, but the uniform fashion the girls were creating, says Mori, “exists in the space between those school rules and breaking them.” Not all establishments gave a hoot though, and in some cases, delinquent girls were given carte blanche to run amok. In other cases the crackdown on micro-minis only encouraged the trend, and some girls started leading a double life. During learning hours, they’d unroll their skirts to an acceptable length; after school, they’d hike their cookie-cutter uniforms up and pull on a pair of loose socks, the other essential ingredient of the kogal look. It was clear girls enjoyed wearing their uniforms out of school hours, but only on their own terms.

NOBUYUKI MORI

Off to one side of the Tombow Museum is a large meeting room where staff from academic institutions and retailers sit in red fabric chairs and plan new duds with Tombow. Headless dummies model Tombow-produced uniforms for the Japanese clothing brands Olive des Olive and Comme Ça Du Mode. The meeting room is a lab of sorts as well, to research the latest school trends. The company not only polls teachers and parents, but also investigates schoolgirl tastes by quizzing kids. “Students want something they can wear after school,” says Sano. This often means fashion that looks like a school uniform but that is, in fact, fake.

CONOMI

Diplomatically cute

IN 2008, the Japanese Foreign Ministry selected three women to be Ambassadors of Cute (Kawaii Taishi), including seifuku-wearing actress Shizuka Fujioka, who was nineteen. The Ministry hoped to capitalize on the popularity of cute Japanese things abroad and Fujioka saw her selection as a huge honor. “I think they picked me because I look good in a uniform.”

MOON THE CHILD

Fujioka had already graduated from high school, where she was disappointed by her school’s homely uniform. She now owns five sets of store-bought seifuku for her role, preferring the blazer and plaid skirt look, because, she says, “Sailor suits are way hard to coordinate!” She borrows the rest of her wardrobe from online retailer CONOMi, where she moonlights as an uniform adviser. “If you think school uniforms are cute,” she says, “you shouldn’t hesitate to wear them—even if you’ve already graduated from school!”

Her ambassadorial post ended in 2009, after a year of smiling and speaking at cultural events such as the Japan Expo 08 in Paris. According to Fujioka her role was to show the whole world “how cute Japanese school uniforms are.” Mission accomplished.

For girls in their mid-teens the uniform symbolizes a brief period in their life when they are free, unbound by adult matters like career, marriage, and children. There’s schoolwork, sure, but as teenagers they are cushioned from the world around them. They’re not children, and they’re not quite adults—yet they have more freedom than both. Anything is possible. So many girls yearn to wear uniforms even when their schools don’t require them. And if some girls think their own school’s outfit is dorky, they change into clothes that, to the untrained eye, look exactly like school uniforms. Whether it’s during school hours or after class and weekends, the uniform is a blossoming beacon, bluntly signaling to society: I am a schoolgirl, young and free.

CONOMI

This demand has led some boutiques to hock cute, unofficial uniforms under the guise of “fashion” in order to sidestep any run-ins with schools. Online retailer CONOMi, for example, specializes in coordinating schoolgirl looks yet says it doesn’t sell school-approved uniforms, but rather, “preppy-inspired fashion.” These faux uniforms are called nanchatte seifuku (just kidding uniforms). In 2008, CONOMi opened a store in the schoolgirl shopping paradise of Harajuku and launched an in-house clothing brand, arCONOMi, the following year. Some customers even show up in full school regalia to get advice on the fine art of matching bows, vests, and plaid skirts or what necktie goes with their school-issued blazer. “My school’s uniform was not so cute,” says a twenty-one-year-old CONOMi staffer in full uniform get up, “and I always ached to wear fashionable school clothes.”

Back in the Tombow museum, Sano is sitting at the table in the large meeting room, surrounded on all sides by mannequins in school clothes. When asked if he thinks uniforms will vanish, his reply is frank. “Not in Japan. Uniforms will always make the schoolgirl aware of what she is and her academic purpose. Japanese people take great pride in their roles in society. So, policemen should look like policemen. Nurses should look like nurses. And schoolgirls should look like schoolgirls.”

Japan’s coolest skirts

ACCORDING TO URBAN LEGEND, the shortest school skirts in Japan are found in bitterly cold Niigata Prefecture, located off the Sea of Japan. While skirts started to inch down in Tokyo at the turn of the millennium, Niigata girls kept hiking them up until they hovered around eight inches (20 cm)above the knee, compared to Tokyo’s six-inch (15 cm) average. These girls think nothing of walking through the snow with their bare thighs covered in goose bumps. The Niigata girls even accentuate their limbs by wearing short socks that show more leg.

While schoolgirls think the micro-minis are cute, the Niigata PTA doesn’t, and they kicked off a “Proper Dress” campaign in 2009. Posters dotted Niigata school halls, telling schoolgirls that shortening their outfits was prohibited, and the PTA also distributed long-skirt propaganda that implied getting good grades and wearing tasteful uniforms were somehow connected.

Manufacturers like Tombow have even devised ways to keep schoolgirls from rolling up their skirts: such as waist bands so thick they’re impossible to fold or when rolled reveal the school’s unflattering crest. In Hokkaido, Sapporo’s Municipal Minamigaoka Junior High School went as far as replacing skirts with slacks, which quickly stopped any short skirt problems. Stopped, we should say, until some girl rebel decides to take scissors to them.

Ironically the best defense against short skirts may prove to be cyclical fashion trends. In early 2009, the Japanese media noticed that girls in idyllic Nara, the country’s ancient capital, were wearing 1980s-style long skirts and were even calling short skirts “dorky.”

NIIGATA COLLEGE OF ART & DESIGN

Get loose

THE MOST NOTORIOUS ITEM in the Japanese schoolgirl wardrobe would have to be loose socks. In the mid-1990s the kogal look was defined by them and they have come to symbolize a certain type of schoolgirl—one that is sexy, rebellious, and very cool. But originally, these infamous socks were American.

Eric Smith, an attorney by trade, hails from three generations of sock makers. In 1982 he started his own company, E.G. Smith, after adapting a woollen hunting sock design from his father’s company. Eric changed the material to cotton, and managed to capitalize on the 1980s Flashdance fitness craze. By the early 1990s, the New York–based Smith was looking to expand and struck a Japanese distribution deal with a textile company in Osaka called WIX.

Various stories exist to explain how the socks then became popular with Japanese schoolgirls, including one that has schoolgirls in frosty Miyagi Prefecture choosing them purely to keep warm. But Smith and WIX company president Takahiro Uehori have another story. “Originally, we launched an E.G. Smith display at a SOGO department store in Yokohama in 1993,” says Uehori. “Two high school girls bought the white boot socks and wore them to class. Before you knew it, the look had caught on at their school.” Rigid school dress codes called for white socks, and Smith’s socks were the antithesis of regulation tighty-whities. The boot socks—later dubbed “loose socks” for the way they hung—flattered short schoolgirl legs, making them appear long and slender. A fashion reporter noticed the Yokohama fad, penned a tiny blurb on the twelve-inch (30 cm) socks, and the trend spread across the country like a bad case of mono. “Loose socks weren’t your typical short-lived teen trend,” says Smith, “this one lasted ten years.” Each generation wants something to call its own, and for girls during the 1990s, loose socks were it. “The self-expression became a uniform in itself,” says Smith. “It expressed an entire generation of women.”

ERIC SMITH

Schoolgirls may have loved them, but schools didn’t. “When loose socks first caught on,” Smith says, “schools banned girls from wearing them. Which only fueled their proliferation.” Suddenly the socks weren’t just a fashion statement, they were a national obsession. “On trips to Tokyo, I’d visit Shibuya Station at three in the afternoon,” Smith says. “Schoolgirls would be changing out of school-regulation knee-high socks into loose socks to go meet their friends. I think this caused the loose socks to be fetishized by some businessmen.”

By the mid-1990s, after reports that schoolgirls were meeting older men for enjo kosai (paid dating), loose socks were no longer just associated with schoolgirls, but with sex. Enjo kosai preoccupied the tabloids and the Japanese government. And by the end of the 1990s, new regulations cracked down on underage-sex-for-money. But schoolgirl characters were already turning up in porn films wearing loose socks, and massage parlors and sex clubs had young looking women decked out in the socks. The original rebellious meaning of loose socks had been twisted by the media so that even today they carry sexual connotations.

ANDREW LEE

Stuck on you

THE SECRET behind how girls managed to keep their loose socks up? Glue.

In the early 1970s the president of chemical company Hakugen noticed his granddaughter fretting about her school socks falling down. In 1972, the company launched a roll-on glue dubbed “Sock Touch” that could be used to stick knee-socks to the skin of your calves to keep them in place. In the following decade fashion trends changed, however—skirts got longer and socks got shorter. Sock Touch lost its touch, and in 1985, Hakugen stopped producing the adhesive.

But when loose socks went supernova in 1993, the company took notice and re-introduced their Peanuts branded “Snoopy Sock Touch.” After having its production halted for almost a decade, Sock Touch was a smash. Hakugen geared up its sock-glue production, rolling out Disney-themed Sock Touch, perfume-free-sensitive-skin Mild Sock Touch and Super Sock Touch, recommended for “furious sport-like movement.”

HAKUGEN

Navy socks

BY THE YEAR 2000, even the strongest Sock Touch could not hold up the popularity of loose socks. They were no longer a cutting edge high school trend, but rather something junior high kids wore in hope of seeming grown-up. Navy-colored knee-high socks were the next big thing. But even then girls needed a way to express themselves and chose socks bearing the logos of famous brands, such as Burberry, Polo, Vivienne Westwood, and even Playboy.

By 2013, however, some schoolgirls began wearing navy socks under baggy loose socks in a convergence of both trends.

CONOMI

Honey, I shrunk the uniform

WHAT BETTER WAY to remember your schoolgirl days than with your uniform... miniaturized? Tokyo wedding-dress company Petite Leda does just that. Mini blazers, tiny skirts, small sailor suits—you name it.

Petite Leda began crafting one-of-a-kind pint-sized school uniforms after blushing brides wanted a way to memorialize their student years. Former schoolgirls can have the company make the mini clothes from the original fabric—even using their uniform’s actual buttons. For those unwilling to part ways with their precious schoolgirl threads, Petite Leda will find matching fabric. They’ll even sew the former schoolgal’s name on the miniature uniform’s inside, just like the real deal.

According to Petite Leda, the 15-inch (38 cm) high get-ups are extremely tricky to make, with the uniform collars and the sleeves being the most difficult. Since each is different, there isn’t a set pattern per se, meaning that Petite Leda’s expert seamstresses must try to capture the essence of the original uniform as a small-scale replica. Quality craftsmanship like this ain’t cheap: the pint-sized replicas cost 31,500 yen (US$320). The mini clothes are available as stand-alones or versions fitted to small teddy bears.

PETITE LEDA

Middle-Aged Sailor-Suit Dude

DURING THE WEEK, fifty-year-old Hideaki Kobayashi is a computer engineer, working on algorithms to solve image processing problems. On weekends, he’s a Japanese schoolgirl.

How does a mild-mannered computer engineer turn into a schoolgirl? First, Kobayashi got interested in taking cosplay (costume play) photographs of manga, anime, and video-game fans dressing up as their favorite characters. When exhibiting his photography at a design event in 2010, and hearing that a well-known cross-dresser would be checking out his pics, Kobayashi decided to dress up as a schoolgirl. He was surprised at the positive reactions his outfit garnered at the event. But it wasn’t until the following summer that he wore the outfit out among the general population when a ramen restaurant in Kanagawa offered a free bowl of noodles to anyone over thirty years old who came dressed in a sailor-type uniform.

“Nobody took up the ramen shop’s offer in the first month,” Kobayashi recalls. “A friend of mine recommended I go. I was the first one to get a free bowl of ramen.” After that, Kobayashi was hooked and began wearing the outfit in Tokyo. Online, people began buzzing about a bearded man in a sailor suit. The gray-haired man in the cute schoolgirl uniform and the braided beard cut a striking figure. Middle-Aged Sailor-Suit Dude was born!

“The sailor suit is a symbol of cuteness,” says Kobayashi. “I think it makes middle-aged guys feel nostalgic for when they were in school and had a secret crush on a female classmate. Well, that’s what I imagine, because actually, I went to an all-boys school.” Kobayashi wasn’t a fan of the boys’ school uniform, saying it made him feel “tied up.”

Now that Kobayashi is an internet celebrity with his own website (growhair-jk.com), he’s been able to parlay that into television appearances. He’s even involved with a sugary sweet pop group called “Chaos de Japon,” populated with actual junior high schoolgirls, not just as the group’s photographer and one of its producers—he’s also a fully fledged member. “Now, I have to follow the rule imposed on members: I’m prohibited from falling in love with someone,” Kobayashi says. “If I were found violating the rule, I would have to shave my beard off.”

PHOTOS TAKEN BY HITOSHI IWAKIRI

Kobayashi isn’t being serious. Then again, maybe he is. There’s a certain playfulness about his sailor-suit schtick. It’s unusual, sure. But it’s also fun and oddly cute to see a middle-aged man in a schoolgirl uniform riding the Tokyo subway or flipping through a magazine in a bookstore. In a way, it breaks up the monotony of urban life. Here is someone doing what they want, instead of being constrained. For Kobayashi, the schoolgirl uniform is liberating.

“People are surprised when they see me in person, because they’ve seen me on the internet or on TV,” Kobayashi says. “They rush up to me and ask to shake my hand or take a picture. That makes me feel good, and I feel like I’m doing something good in society too.”