Читать книгу Japanese Tattoos - Brian Ashcraft - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

EXPLORING JAPAN’S TATTOOING TRADITION

THE WORLD OF JAPANESE IREZUMI

It was early spring. The weather was still too cold for the cherry blossoms to cover Japan in hues of pink and white. My coauthor Hori Benny, an American-born Osaka-based tattooist, and I took an early morning bullet train to Horiyoshi III’s Yokohama studio. Our interview with the world-famous tattooer was supposed to be only an hour, but we ended up spending the day with him, the first of several visits.

During our talks, Horiyoshi III, who was busy working on a succession of clients, generously shared his insights. One of them in particular stuck with me as I wrote this book: “In a funny way, everything in Japan is connected to irezumi,” he said, using the Japanese word that refers to tattoos. The statement couldn’t have have been truer. In irezumi you’ll find expressions of the seasons, the folklore, the religions, and many other aspects of Japanese culture.

WHAT DOES “IREZUMI” MEAN?

Irezumi isn’t simply the Japanese word for “tattoos.” Throughout the country’s history, different words have referred to tattoos, and the word irezumi itself has been written with different characters, each having a separate meaning or nuance, whether that was the irezumi (入れ墨) that was a branding mark, meted out as punishment to criminals, or the irezumi (刺青) that was done of free will. Other words have been used, such as irebokuro (入れ黒子), which dates from the 1700s. Additional old terms include mon mon (紋々), where “mon” refers to a crest; or monshin (紋身), which literally means a crest on one’s body. These are not used today. The word horimono (彫り物), however, still is; it can refer to tattoos or any other engraved thing. More recently, the term wabori (和彫り), which means “Japanese engraving,” was coined in the 20th century to refer specifically to Japanese tattoos.

AN ANCIENT TRADITION

Tattoos go back as far as Japan’s recorded history. Japanese accounts as early as the fifth century mention punitive irezumi, but tattoos had other purposes before that. For example, a third-century Chinese account mentions that Japanese people tattooed themselves to mark social class and protect themselves from harmful sea creatures. If true, this would support the theory that the patterns on the faces of the prehistoric Japanese terracotta burial figures known as haniwa are not painted, but tattooed.

There are other tattoo traditions in Japan with a long, rich history, such as that of the Ainu people in Hokkaido. Their facial and hand tattoos are from a different tradition than those found on Japan’s main island in cities like Osaka and Tokyo, and they fall outside the purview of this book.

BECOMING A HORISHI

In Japan, horishi (tattooers) study and train for years to master their craft. In the past, that meant a lengthy apprenticeship in which the apprentice, or deshi, would clean up the studio and practice drawing and tattooing himself (or, more recently, herself). This would continue until the day the master, or shisho, finally deemed the pupil good enough to work on actual clients.

Some tattooers stick close to the master’s style or continue to work from iconic designs, while others might try to add their own interpretation or go off in another direction altogether. Once a tattooer debuts, “Hori” (彫), which refers to engraving or carving, is added before their name. Calling oneself “Hori” explicitly states a mastery of craft and artisan stature. It’s the irezumi equivalent of “Dr.” or “Prof.”

Suikoden hero Roshi Ensei as depicted by influential Japanese woodblock artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

A bodysuit featuring Emma-o, the Buddhist god of hell. Emma-o metes out sentences and rules the underworld. His hat reads 王 (ou), meaning “king,” and the wheels represent the Buddhist Wheel of Law.

In this sculpture, a Japanese tattooer is using the tebori hand-poked method to tattoo a woman’s back with a dragon.

This system has created close-knit tattoo families called ichimon. Even after graduating and setting up shops of their own, former apprentices continue to have close relationships with their master and are expected to take care of their teacher should something happen. Not all of Japan’s best tattooists have gone through an apprenticeship. What they all share is a serious study of tattoo motifs and design, whether with a mentor or not.

A LIFESTYLE CHOICE

People in Japan get irezumi for a variety of reasons. Some get them to protect their bodies, or for religious reasons. Others get tattoos because they look good.

Whatever the reason, irezumi is a lifestyle choice—and in Japan, a brave one at that. Even today, when tattooed people in Japan go out in public, unless it’s a specific special occasion, such as a religious festival; or a safe environment, such as a bohemian district of a big city, most cover up their ink. This is because of the widespread belief that only Japan’s gangsters, the yakuza, have irezumi, so if you are tattooed you are dangerous. Covering up one’s ink is not only a courtesy to avoid unsettling others, but is also to protect from discrimination, whether applying for a job or renting an apartment. My local bartender in suburban Osaka has had his biceps inked with Polynesian-style “tribal” designs. When I asked him why he hadn’t gone with Japanese irezumi motifs, such as flowers or Buddhist gods, he replied, “Because I don’t want to be confused with a gangster.” There are also notions in Japan that tattoos are dirty, because unclean needles spread a whole array of diseases, as well as a Confucian belief that it is disrespectful to modify the body bestowed on you by your parents.

There is, however, a long, proud tradition of firemen, blue-collar workers, and artisans getting tattooed for religious convictions, to protect their bodies from hazardous work, and simply because irezumi look damn cool.

UNDERGROUND TATTOO CULTURE

Although largely hidden, irezumi culture remains strong. If you look closely, you’ll catch glimpses. A glimpse of red under a sleeve. Some black at the edge of a pair of shorts. Flashes of yellow or blue. Irezumi are designed to be covered and worn under clothes. But because tattoos aren’t out in the open in Japan as they are in the West, when you finally do see them, they have enormous impact and power. This is what makes irezumi unique; this is their appeal. Generally speaking, irezumi are personal and private, unlike Western-style tattoos, which often seem to be for show.

In Japan, foreigners with tattoos are less likely to be judged harshly than the locals who have them. The common assumption is that Western-style tattoos are for fashion, while Japanese ones are for unsavory types. This is why inked celebrities like Johnny Depp or athletes like Brazilian soccer star Neymar Jr. can appear on television or in print ads with their tattoos on display. Meanwhile, many tattooed Japanese celebrities tend to cover their irezumi for fear of alienating fans or being misrepresented. Most people in Japan don’t see tattoos during daily life. The chances of you seeing someone’s irezumi at a PTA meeting, at a convenience store or McDonald’s, or even on the subway are very, very low.

For all of that is made of irezumi’s connection to Japanese organized crime, it’s important to remember that, during the periods in which tattooers were persecuted and could be arrested for practicing their craft, it was the yakuza who kept tattooers employed. Regardless what you think of yakuza or their activities, if you like Japanese tattoos, the fact that yakuza have kept the tradition alive should be respected.

The wooden doll (called a kokeshi) makes a striking comparison between the courtesan and the doll itself. Kokeshi can be tokens of friendship, but are sometimes compared to phalluses, underscoring the lush, sexualized themes in this tattoo.

Hannya masks (see page 112) are iconic and powerful. The back is the body’s biggest canvas for irezumi—and what better way to make a statement than with a giant Hannya?

TATTOO PROHIBITION

Today, tattooing isn’t banned in Japan, but the practice exists in a legal gray zone. In 2001, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare classified tattooing as a medical procedure, with the rationale that only a licensed health care professional can penetrate the skin with a needle and insert pigment. The government, however, does not issue tattoo licenses, and the industry continues to be unregulated. In some parts of the country, there are large, open tattoo shops right on the street with clearly marked signs. In other regions, tattooers work out of unmarked studios and rented apartments.

From the late 19th century to the end of World War II, tattooing was illegal in Japan. During the U.S. Occupation (1945–1952), the tattoo ban was finally lifted after an American officer under General Douglas MacArthur met with Horiyoshi II of Tokyo. (Note: this Horiyoshi family is different from the Yokohama Horiyoshi line.) The U.S. military might have been more accepting of the craft due to its tradition of service members getting inked.

Irezumi prohibition had been part of an effort to modernize and align Japan with Western morals. During the 19th century, officials issued various edicts against tattooing (one 1811 edict pointed out that, horrors of horrors, irezumi were fashionable among the country’s youth). These went largely ignored, but in 1872, the Tokyo government announced the Ishiki Kai ordinance, which was soon followed by a similar national decree. The Ishiki Kai ordinance banned major and minor social transgressions, including peeing in front of stores, being naked in public, mixed communal bathing, selling pornography, and tattooing. Those who violated serious infractions, such as tattooing, were fined. Those who couldn’t pay the fine were whipped. People who already had ink could avoid police trouble by paying for a permit.

The ban, however, applied only to Japanese people. The government never anticipated that some foreign visitors, including those from the upper echelons of society, would become enamored of tattoos. There was an obvious gap in how foreigners saw irezumi and how the Japanese ruling class saw them. Lord Charles Beresford, an admiral and a member of British Parliament, got tattooed in Japan, and later recalled how the country’s upper crust was astonished because they thought it was only for the “common people.”

A traditional American black panther design infused with Hannya mask elements.

Irezumi have provided plenty of fodder for Japanese pulp writers.

Not all the 20th-century pulp stories were set in the modern day. This one shows a traditional horishi at work.

No Tattoos Allowed

Check Your Ink At The Door

At hot springs, public baths, swimming pools, and gyms across Japan, you’ll see signs that state the same thing: folks with tattoos cannot enter.

It wasn’t always so. In the years after World War II, when many middle- and lower-class families in towns and cities still used the local bathhouses because they didn’t have tubs at home, establishments couldn’t be picky about clientele. Everyone needed to bathe.

As the Japanese economy grew in the 1960s and 70s, and as urban homes became more luxurious, regular public bathing became less common. This also meant that tattoos were seen more rarely. Bathhouses and hot springs became more strict about who they would and would not let in.

These days, not all establishments have tattoo bans. There are hot springs and bathhouses that allow inked bathers (though they might ask you to cover your tattoo with a towel or even a special sticker). Some that technically don’t allow them might turn a blind eye, especially for international visitors. Don’t expect that, though: In 2013, for example, one Hokkaido hot springs denied entry to a New Zealand woman with traditional Maori facial tattoos. The incident made international news.

This warning sign was posted at a pachinko parlor entrance. Note that it uses the irezumi kanji (入れ墨) that refers to punishment tattoos.

Inked Royals

Blood Blue, Black Ink

During the late 19th century, tattoos became a fad among European royalty. For bluebloods, permanent ink was the ultimate souvenir of an exotic voyage.

The British king Edward VII helped to kick off this trend after getting a Crusaders’ cross tattooed on his forearm in Jerusalem. As a boy, Edward wore naval-inspired playsuits and popularized sailor clothes among the Europeans, which later spread to Japan. That Edward was quite the trendsetter!

His sons, Prince Albert Victor and the future King George V, both got dragon tattoos while visiting Japan in 1881. The last Russian Tsar, the future Nicholas II, also got a dragon tattooed on his arm while visiting Japan in 1891. During that trip, there was an attempt on his life. He survived, but didn’t make it through the Bolshevik Revolution.

Regal tattoo enthusiasts like Nicholas II were irezumi’s earliest ambassadors.

THE RISE OF ONE-POINT TATTOOS

One-point designs are popular today in Japan, especially among people who want some ink but don’t want to make the commitment that bodysuits or large back pieces require. In Japan, one-point designs traditionally have been a way to distinguish Western-style tattoos from the irezumi house style. Many tattooers in Japan are equally fluent in both, and can do big pieces surrounded by gakubori (see page 136) and isolated one-point tattoos. This flexibility ensures steady work, but it’s hardly a new phenomenon.

During the 19th century, Japanese tattooers began modifying their designs to appeal to foreign customers. Most tattoo tourists got isolated one-point tattoos depicting things like samurai or geisha. In comparison, the full bodysuits, with their intricate designs and elaborate backgrounds, must have looked like artistic marvels to foreigners. No wonder they influenced a generation of talented Western tattooers like Sutherland MacDonald and George Burchett.

Few visiting Japan, however, completely covered themselves in ink. The reason was convenience: Most simply didn’t have the time and wanted something that could be done quickly. There were exceptions, though. Over the course of several months in 1872, Charles Longfellow, son of the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, got several years’ worth of irezumi, including an image of Kannon (page 89) on his chest and a koi fish (page 73) ascending a waterfall on his back. Because so much work was jammed into a short period of time, Longfellow didn’t have the time to recoup between sessions, so he got morphine injections to make it through.

In the West, the popular 19th-century notion of tattooing was based more on stereotypes than in reality.

Japanese motifs such as this swimming goldfish also make wonderful stand-alone designs.

In traditional American tattooing, skulls and roses are often paired. Here, waves and peonies replace the roses, underscoring the life-and-death theme and giving the tattoo a decidedly Japanese feel.

During 20th century, one-point tattoos were the dominant style in the West, while large interwoven designs were the most common in Japan. But by the early 1980s, something funny was happening: a new generation of Japanese born after World War II who were into American and British culture wanted foreign-looking one-point tattoos. Around that time, American tattooer Don Ed Hardy inked Western-style designs on the members of the Black Cats, a popular Japanese rockabilly band. Just like that, a clear division between the words “tattoo” and “irezumi” was drawn. Tattoos were fun and fashionable. Irezumi were scary. This separate terminology has relaxed considerably. Some Japanese tattooers now use the words interchangeably. Others, however, still do not.

WHY JAPANESE TATTOOS CHANGED

Modern life influences the way tattoos are executed on physical and subconscious levels. There are no truly traditional Japanese tattoos because people don’t live in a traditional world. Western fashion, the internet, Japanese TV shows, and Hollywood movies all create a vastly different visual landscape. All of this impacts tattoos, reflecting contemporary visual culture. This is most evident in anime-infused geek ink.

Even if the designs hark back to an earlier era, modern tattooers can put a contemporary spin on their work with eye-popping hues. Colors like bright oranges, strong navy blues and vibrant purples are not originally part of irezumi’s color set. It wasn’t until the decades after the Second World War that a greater variety of hues like purple and orange started being used in Japanese tattooing in a big way. A whole host of new designs followed, along with a new way of thinking. Irezumi underwent one of its most significant changes ever.

ABOUT THIS BOOK

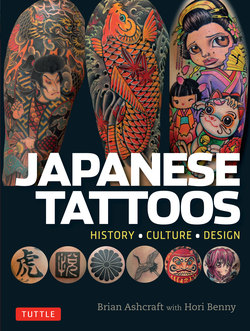

Irezumi are still an underground phenomenon in Japan; indeed, that’s part of their appeal. Because of this, irezumi are enveloped in mythos and misinformation. My coauthor Hori Benny and I have seen plenty of non-Japanese with either faux or downright awful “Japanese-style” tattoos. Over the course of researching, interviewing, and writing this book, we consulted numerous friends, colleagues, experts, and total strangers with the goal of introducing and decoding the most prevalent motifs so that English speakers can have a better understanding of their meaning and hopefully get Japanese tattoos that can be worn with pride—as they should be.

The Birth of the Tattooing Machine

The Electrical Revolution

Samuel O’Reilly patented the first tattoo machine in 1891. The New York City tattooist based his device on Thomas Edison’s motor-powered electric pen. Twenty days later, in London, Thomas Riley filed a patent for a single-coil tattoo machine, which had been created from, of all things, a modified doorbell.

TATTOOIST PROFILE

HORIYOSHI III

JAPAN’S MOST FAMOUS TATTOOIST

“Are you ready?” Horiyoshi III calls to the customer in the waiting area. The unassuming client looks to be in his late 20s and seems like a typical button-down white-collar worker. He enters, greets the tattoo master with a bow, and undresses, revealing an irezumi bodysuit. He lies down on his stomach. On his back is a depiction of Buddhist hell—Horiyoshi III’s handiwork.

With international exhibitions of his paintings, numerous publications on his tattoos and his designs, and even a clothing line named after him, Horiyoshi III is perhaps Japan’s most famous tattooist. He is also a dedicated scholar of the form. The studio, a second-story walk-up in Yokohama, is lined with books. “I have another couple thousand or so at home,” he says. “This is because I’m serious about learning.”

Horiyoshi III wasn’t always a keen student. “Growing up,” he admits, “I was a hoodlum.” Born Yoshihito Nakano in 1946, he began working as a welder in a Yokohama shipyard after finishing junior high school. “Lots of shipbuilders had tattoos,” he recalls as he pulls on a pair of latex gloves. Nakano saw his first tattoo at age 11 at a public bathhouse. “It was a culture shock, but I thought it looked pretty cool.” At 16, he began tattooing himself. This was a time when information about tattoos was still scarce and techniques were only passed down from master to apprentice. “It was all guesswork,” he says. “I tattooed my leg using needles fastened to disposable chopsticks.”

At age 25, Nakano finally secured an apprenticeship with Yoshitsugu Muramatsu (aka Horiyoshi I), a well-known tattooist in Yokohama. Nakano showed up at Muramatsu’s studio unannounced after his letters had gone unanswered. “Of course, I was nervous,” he says. “There wasn’t a sign outside the studio like there are on my shops today.” It wasn’t a place you could just pop in for a chat. “It was completely underground,” he says, recalling how the studio had the “strong scent of the outlaw.” Unlike today, the majority of the clients were yakuza. Horiyoshi I, who had already named his own son Horiyoshi II, gave Nakano the “Horiyoshi” name as well. In 1979, after a lengthy apprenticeship, Horiyoshi III was born.

The tattoo machine fires up, its buzzing echoing through the studio. Horiyoshi III puts Vaseline on the customer’s back. “I used to think I’d rather quit tattooing than use a machine,” he says, as he begins shading in the Buddhist hell. Horiyoshi III also practices tebori, often called the “hand-poked method” in English. For centuries, tattooing in Japan was synonymous with tebori, while the stereotype was that the tattoo machine was for foreigners. For Horiyoshi III, that would change in 1985, when he attended a tattoo convention in Rome and saw firsthand how efficient, versatile, and easy to use the machine was. He attended with his friend American tattooist Ed Hardy, who not only used the machine, but was also better versed in irezumi than Horiyoshi III. Japanese tattooing wasn’t simply a method of inserting ink, but rather, an entire history and catalogue of iconography.

Master tattooer Horiyoshi III in his Yokohama studio.

After the Rome convention, realizing there were those outside Japan who knew more about his country than he did, Horiyoshi III arrived back in Japan with a new-found thirst for Japanese art, history, and culture. It wasn’t simply a matter of pride. It was the beginning of a lifelong pursuit of knowledge. “Mankind has made it this far by studying,” he says. “The tattoo machine, for example, was the result of someone studying.”

Horiyoshi III began spending his days in libraries and bookstores. “I had this small camera that I’d use to snap photos if there was a book with only one page I wanted,” he recalls. “The shopkeepers would get pissed at me.” He did buy countless books, and filled his home and studio with them. “When you have lots of knowledge, you get wisdom,” he says. “When you have lots of wisdom, you get an endless flow of original ideas.” The impact is clearly evident in his art.

“Personally, I don’t like the word ‘art,’” Horiyoshi III says. Admirers of his work, however, would be quick to call it just that. “You shouldn’t call what you do art—but I won’t stop others from using the term,” he adds. It’s not simply that the work should speak for itself, but also that Horiyoshi III respects the tradition of the shokunin—the craftsman. “I would call myself a shokunin, not an artist,” he explains.

A young badass Horiyoshi III poses with a tosa, a Japanese fighting dog that’s banned in many countries.

The Yokohama Tattoo Museum houses numerous important artifacts, such as these Hori Sada spring-themed sleeve designs. On the right arm, there are peonies; cherry blossoms are depicted on the other.

“In the art world, you are allowed to fudge things,” he continues, adding that artists can call “anything” art—even dog poop. “You cannot do that in the world of the shokunin.” Irezumi is a language, with its own grammar and rules. “If you don’t know the meaning of the symbols and the stories, you can’t tattoo as well. Tattooing becomes superficial. Meaningless.”

Or—just as bad—it can lead to mistakes. “Even if you see a tattoo that looks beautiful, if there’s something that’s not quite right, well, that’s a mistake,” he says. “It’s like a Bentley with the steering wheel in the back seat,” he adds, chuckling.

Horiyoshi III’s invention, a modern tebori tool that can be sterilized, rests atop the antlers. Below are traditional tattooing tools.

Horiyoshi III pauses. “This is just my opinion, but there isn’t traditional tattooing in Japan anymore,” he says. “In the old days, the needles and inks that tattooists used were closely guarded secrets. There was none of this—” he gestures toward the fluorescent lights overhead and the carpeting on the floor. “Tattoos were done on tatami mats by sunlight or candlelight, using old tools.”

“Even if I were doing this tattoo by tebori, it wouldn’t be traditional,” he adds. The heater keeping the room warm on this chilly day would need to be shut off. Inks and colors that might fade easily or cause harm would have to be used, and there wouldn’t be latex gloves and sterilization. That, explains Horiyoshi III, is how tattoos were traditionally done in Japan.

Pointing to the back covered with ink before him, he says, “Rather, I’d call this tattoo ‘traditionalist.’ That’s the word I would use. Calling it ‘traditional’ is disrespectful to the tattooist of the past who worked under the threat of being arrested.”

Horiyoshi III’s work honors the past. Yet it moves the form forward and transforms it, too, whether through his use of different techniques or his creation of brand-new designs that exist in, as he would say, a traditionalist style. All of this is the result of decades of learning—from books, from people, and from life. “I’m still studying,” Horiyoshi III says. “And I’ve been doing this for over forty years.”

The second floor of the Yokohama Tattoo Museum is filled with rare prints, old texts, and countless historical artifacts.

A statue of Horiyoshi III tattooing a phoenix on a woman’s back. In his right hand, he holds the tattooing tool; his left holds a paintbrush in place, which he can use to dab ink on the tool.