Читать книгу Devil's Peak - Brian Ball - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

The big Diesel engine hammered and ground away, pushing back into the cab the smell of burning oil and such a flood of warmth that Jerry groaned aloud halfway between pleasure at being alive and pain at his dead-white nose and fingers. The girl looked sullenly at him, deeply resentful. Jerry surfaced out of his delirium.

“Give him the coffee now, lass,” the driver told her. “Under the seat by you.” His eyes were on the swirling whiteness where the foglights punched yellow holes to the grey wall at the roadside. “Go on!” he said again.

She didn’t answer, but she did rummage under the seat. Jerry was aware of her hostility; it was the driver who had saved him.

“Here,” she muttered, slopping the smoking coffee into a cup. “Don’t spill it on me coat! It’s suede!”

“Brenda’s a hard-faced cow,” the driver said.

Brenda swore at him.

Jerry had met the sort before, though not one so hard so young. He was fairly sure that she would have left him to die in the snow, given a choice. The driver, whose name he didn’t know yet, had hesitated. He was a big, muscular, middle-aged man with a comfortable look about him; there’d be a family, Jerry thought. Obviously he’d weighed up Jerry’s condition against the situation in which he’d been caught. And either his basic humanity, or his fears of an investigation should Jerry be left, had won. He would know that the tanker’s presence would have been noted by someone. Jerry preferred to think that he’d done the right thing by instinct.

His fingers had almost no feeling in them, but he could hold the mug of coffee steadily enough. The trouble was that the steam was causing his nose an exquisite agony; through tear-filled eyes, he could see the girl’s hands. One was tattooed on each finger: L-O-V-E, the four fingers spelt. What was on the other? He couldn’t see. It seemed incredible to him that he was alive and warm, that the bitter snow was outside and he within. He remembered vaguely that he had tried to cuddle against her thin body: and she hadn’t liked it. The hell with the miserable bitch; and her fingers.

“What were you doing out there anyway?” asked the driver, as they swept around a series of sharp bends,

“Walking,” said Jerry. “It was fine when I set out.”

“What’s your name, then?”

“Howard. Jerry Howard.”

“I’m Bill Ainsley. You’ve met Brenda.”

“Hello,” said Jerry suffused with gratitude.

“How’re your hands?” asked Bill. “I were Army in the war. I’ve seen frost-bite. You haven’t got it.”

“My hands must have been underneath. They’re all right. My nose hurts.”

“Your nose wouldn’t get frostbitten. They never do.”

Brenda watched each man, turning from one to another like an umpire. She had a thin pink suede coat over a tiny pink skirt. Long black tights ran down to red woollen socks and heavy boots. Like all the others, she had a duffel bag stuffed to the top. And that was all.

“Wrenched your ankle too?”

“I fell over. I got stuck climbing.”

“Climbing! Climbing bloody what?” exclaimed Brenda in her pit-village voice.

“A rock face,” Jerry told her. “Toller Edge.”

“What for? You must be mad!”

“There was two killed climbing near Capel Curig when I went through last Easter,” said Bill. “Came off together, straight down a thousand feet.”

“Silly sods,” said Brenda.

She had dark, malevolent eyes that had been filled with a dreamy kind of fire when they had first focused on Jerry; now they were sharp and dark and hating. Bill grinned at her.

“You’re lucky to have time,” he told Jerry. “You a student?”

“Yes. That’s right.”

“Students!” spat Brenda. “They want stuffing, all of them!”

“She doesn’t like students,” explained Bill. “Two of them tried to go for her one night in the back of a Mini. She only likes lorry men.”

Brenda swore coarsely.

“Thought you were a student or a teacher,” Bill said. “The beard.”

Brenda swore again.

Jerry saw that she was almost beautiful. Her figure wasn’t ripe yet, but it would be. She was craning forward, her neck arching in a sweet curve.

“Aye, wheer you’re going?” Brenda shouted. “This isn’t the Manchester road!”

“No,” explained Bill. “I can’t turn the tanker till we get to the end of this one—there isn’t a place to turn for miles.”

“Then wheer are you going?”

Jerry was interested by this time; so far, he had been concerned with only the fact of his survival, the pain of sensation returning to his body, and the strange dislike of the girl.

“I could maybe get a lift back to Sheffield,” Jerry said, hearing the crunching of the massive eight tyres on drifted snow. “A bus maybe.”

“No chance,” Bill said. “No driver’s going to turn out tonight.”

“Wheer are we going!” Brenda spat insistently.

The caff. Castle Caff.

“That dump!”

“I can turn in their yard. Get back on to the road.”

Jerry knew this place. It served as a halting-place for the men who drove the vast lorries over the backbone of England through lanes which had been laid down for carts; the caff was useful to the walkers and campers too, though they were tolerated rather than encouraged.

“I’m not going theer!” the girl shouted.

“Then you’ll have to get out and walk, lass.”

“Oh, you sod.”

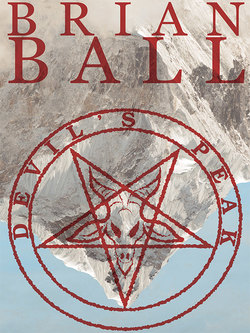

“And sod you,” said Bill equably. The huge tanker skidded for seconds on locked wheels as he took it round a steep curve. Jerry looked out and saw a glimpse of lights far below in a break in the blizzard. They were climbing now along the shoulder of the rock he had seen from the gritstone edge: they would climb further until they were halfway up the shivering, loose shale face of Devil’s Peak, right up to the curious projection of rocks that from a distance, and in the right light, had the configuration of a pair of curved horns. All the local peaks had names—Mam Tor and Chee Tor and Mam Nick—usually the ancient names of forgotten peoples. None was so appropriately named as this. It seemed strange, almost ironical, to be sitting in a tanker after almost freezing to death and then making for Devil’s Peak which had seemed to leer at him only an hour or two ago. But he wanted to go back to Sheffield. It was Friday, and Friday night was beer and darts night.

“Maybe there’ll be a lorry at the caff,” he said. “You know, Bill, going back my way.”

“Could be,” Bill agreed. “Still, you’re out of trouble, aren’t you?”

He looked worried. The unspoken question was in the air. Would Jerry make any comment on the presence of the girl? Jerry sensed the man’s discomfort.

“Why not leave me at the caff?” he said. “You go on—if I can’t get a lift, I’ll stay till morning.”

Bill grinned suddenly, his fleshy face relaxed completely, “Aye. Brenda and me’ll go on to Manchester. Sure you’ll be all right?”

Jerry checked on the condition of his fingers, nose and toes. All seemed to be functioning normally, though there was still a feeling of a tightening and painful expansion of the extremities of his body.

“Don’t worry about me.”

Brenda looked at him: “Who’s worrying?”

“Cow,” said Bill pleasantly. “Soon be at the caff. Can’t stay long, though. The drifts are getting up. There won’t be many more trucks going through after me. Not tonight.”

The girl was pressed against Jerry’s body, but there was little heat to be gained from her; it was as though she could insulate herself from him. He began to worry, for he was normally attractive to women; however partisan the lorry girls might be, this one was hostile in an unusual way. So she’d been messed about by a couple of drunk undergraduates. So what? He found himself angry in return.

“Theer,” said the girl suddenly. There were lights beside the road a few yards ahead. The tanker was moving cautiously up the narrow road so that when she spotted the caff Bill could turn in easily.

“Let me buy you a drink. A meal or something,” Jerry said, as the vast engine was quiet. “Bill. And you, Brenda.”

Brenda pushed past him contemptuously. She said nothing as she jumped into the howling night.

“A cup of tea then,” said Bill. “You all right to get out?”

Jerry remembered how he had been hauled in by the man, a limp and frozen bundle desperate for warmth.

“I’m all right,” he said.

They got down, Bill jumping lightly, Jerry lowering himself tortuously on to his sore ankle. Bill waited for him in the whipping shock of the wind and snow.

He shouted something above the wind. “She’s a cow…always on the hills… still, she’s company on the run!”

The caff was a single-storied building roofed in white-grey concrete panels that sloped away to take the edge off the prevailing wind. The rest of the building was much older—it was built massively from blocks of the local gritstone, green and weathered from exposure to years of howling gales. In be junction of two pinnacles of rock where the caff was built, the wind boiled up the snow so that it danced as if in a tornado’s grip. Snow had drifted to the side of the building nearest the inker to a depth of three feet, up to the windows. It was an odd place to find a caff, but it seemed to suit the couple who ran it. It did a fair business. Not tonight, however. There wasn’t another lorry or car in the big park.

Jerry hobbled his way to the door and pushed inside.

Brenda was already drinking. She was in the act of lighting a cigarette when they came in.

“Shut door quick!” she yelled. “It’s bloody frozen! And I’m not staying here long either!”

Raybould himself was at the counter, hidden from view by a large coffee urn except for the top of his bald head which shone damply in the white neon lighting. He emerged as he heard the door slam shut.

“Hello, Bill!” he called. “You look like Father Christmas—and you look perished,” he added to Jerry.

“I got stuck walking,” said Jerry. “I can’t get back to Sheffield—”

“That you can’t! Road’s blocked t’other side of Hathersage! Just got it from Radio Sheffield!”

“Found him near frozen,” said Bill. “He’d been up Toller Edge.”

Jerry didn’t want a discussion of his encounter with near-death. He shivered, the hot delirium he had felt in the cab returning once more.

“So have you a bed for the night?” he stuttered.

“Aye! You as well, Bill?”

“No. Brenda and me’s pushing on.”

“l wouldn’t,” Raybould said. He was glancing from Bill to Brenda with a wet excitement in his slightly bulbous blue eyes. Jerry could see his nose twitching, as if he were on a strong scent. His features were small, clustered in the middle of his face—eyes, nose, mouth, all scrunched together, alert like a stoat’s.

Brenda saw the look he gave her and snorted. She took her tea across to the big coal fire that blazed furiously into the brick chimney; she sat on a low chair beside a big brass coal-scuttle that Jerry didn’t recall seeing before. But it had been summer then, so perhaps it had been out of sight; there was no call for such a fire when the High Peak was warm and friendly. The two men, Raybould and Bill, talked about the state of the roads to Manchester; Bill was confident that his big red tanker would get through. He wouldn’t stop to put on chains, just for a cup of tea. And he wouldn’t let Jerry pay after all.

“No need for that, lad,” Bill said. “I was glad to help. Doesn’t need paying for. How’s the ankle?”

“Fall, did you?” called Raybould. “We get a lot of broken legs. Those buggers who do the climbing. You’d think they’d know what they were about, what with ropes and helmets and that. But they’re always falling off. We buried one over Christmas.”

Jerry’s heart lurched. He was back on the face momentarily, sick with the realisation that the rock jug had been knocked off and that he’d committed himself to going up. He saw Brenda’s thin smile. She had ungenerous but pretty red lips turned both up and down in an expression that was between a snarl and a look of amusement: Then she turned away and began tracing the pattern along the edge of the brass scuttle.

Jerry fought against the flood of delirium that threatened to overcome his senses. He unlaced his boots, controlling his shaking hands only with difficulty. He inspected his ankle. There was a soggy feel about the tendons on the outside of if the swelling had just started.

“I’ll be all right in a day or two,” he told Bill. Raybould noticed his condition at last.

“Best get yourself dry!” he said. “Brenda, come away from in front of the fire. Put your jacket over the chair. Come on Brenda!”

But she wasn’t listening. Jerry could see her caressing the brass fire-bucket with gentle lascivious movements. T-R-U-E he spelt out on the fingers of her left hand. The long, thin fingers were tracing hypnotic patterns in the firelight; the metal was red and brassily yellow. She stared down, quite intent on her game. Jerry saw Raybould’s face set in an expression of unequivocal lust; in the summer he tried to chat up the girl-walkers, though not when his wife was about. It was their long brown legs that fascinated him. Jerry’s senses began to swim away from him as the glittering brass and the heat and the girl’s insidious movements hypnotised him. He heard the conversation as if through a series of transparent curtains, faintly, distantly.

“Come on, Brenda,” ordered Bill Ainsley. “We’ll get off now.”

Still she didn’t look up.

“That bloody brass tub!” said Raybould. “She always sits over it! Brenda!”

“Wrap up! Get off!” she added, as something white and angry rushed towards her. “Bloody pest!”

Jerry’s eyes had begun to close. He blinked awake as he heard a faint yipping sound: Yip-yip-yip! Yap! Yip-yip! He looked at his feet and saw a white blur, red mouth open, white fragile teeth bared: it was—a chicken? A chicken! Yipping at the lorry-girl, who glowered back at it, snarling her own vicious answer. Jerry shuddered. The chicken had little curls all over its body. Yip-yip! it went. Yip-yip-yip!

“Not a barking chicken!” he said in anguish. “There isn’t such a thing.”

“A barking what!” Bill said. “Lad, you’re bad!”

“Come out, Sukie!” Raybould said, and Jerry realised that he was looking at a frightened and angry white miniature poodle, all thin bones and fluff. “Leave her alone, Sukie!”

The poodle backed off and went to the door leading to the kitchen.

“Barking chicken!” laughed Bill Ainsley. “Coming, lass?” he asked Brenda.

“You could stay,” Raybould offered.

“Oh no she couldn’t!” called a woman from the doorway at the back of the counter. “I don’t want her sort here. Sukie! Go back!” she ordered the poodle.

It was Raybould’s wife, a tall, thin woman of about fifty; she looked at her husband, daring him to repeat his invitation. Brenda stared at the woman. Jerry saw a strange expression in her eyes again, that dreamy, unfocused emptiness he had first seen when he was in a half-conscious state himself. She touched the brass bucket again with her tattooed hands, once, twice. Then she grinned at Bill as any teenager might, jumped to her feet and slouched to the door. Mrs. Raybould watched carefully. Sukie yipped twice in triumph.

“So you’re all right?” Bill asked Jerry.

“No need to worry,” Jerry said. “I’m fine. If you hadn’t got out—”

“Aye, well,” Bill said. “No harm done.”

“If you ever get to the Furnaceman’s in Sheffield—Townsend Street—I’d like to buy you a drink.”

“Aye. All right, lad.”

He called his goodnights and ushered Brenda out into the blizzard. Jerry knew he had been lucky. He sat close to the fire and saw his sweater and anorak begin to steam.

Mrs. Raybould crossed to him:

“Why, you’re wet through! You’re shaking! Sam, get him a blanket! He’ll have to dry off! How about something to eat, if you’re staying? You are, aren’t you? Well, you’ll have to. There won’t be any going back to Sheffield, not tonight. And if that A57 stays open Manchester way, it’ll be a miracle! Now, Sam!”

Raybould went for the blanket.

“Bacon and sausage?” Mrs. Raybould said. “You’ve been in here before, haven’t you?” She petted the little poodle bitch, which sniffed at Jerry.

“A few times.”

“You were with some climbers.”

“That’s right,” Jerry said. The bitch inspected his ankle. Mrs. Raybould did not object. Jerry was suddenly violently hungry. “I could do with that bacon and sausage. And some eggs.”

“Tea and bread and butter,” Mrs. Raybould decided. “You had a girl with you.”

“Yes,” said Jerry. The woman hadn’t been anything like so agreeable when he and Deborah had called in for a meal one day in August. The food was stale, warmed up probably.

“Those lorry girls,” Mrs. Raybould grumbled. “Come in and sit all night with a cup of tea. Especially her. He doesn’t mind. Sukie hates her! Hurry up, Sam!” she called. “I’ll get your meal.”

Jerry leaned forward towards the coal fire and saw what the girl had been entranced by. Around the rim of the coalscuttle was a row of figures. They seemed to dance in the yellow and red flames. Raybould came up behind him.

“Here’s a blanket—get your things off.” Jerry closed his eyes, swaying with drowsiness. He had been near death and he was drunk with heat. “You’re a teacher, aren’t you?” Raybould asked.

Jerry managed to get the soaking tee-shirt off. Then the corduroy trousers. He felt the rough army blanket on his skin.

“Just out by yourself, then?”

“That’s it.”

Jerry didn’t want questions about his escape from death; it was too close, too real. He pointed to the figures:

“I haven’t seen this before.”

“The old scuttle fell to bits, so I use this. It’s heavy to hump about.”

“The engravings are good.”

“Should be. It came from the Castle.”

Jerry blinked in the glare as a burst of blue-red flame shot up the chimney. It had been an odd sort of day, what with the blizzard coming up and the girl hating him. He was aware that he had not recovered from the effects of the climb and the gradual freezing in the drift. It was a sign of complete exhaustion when you had fantasies like thinking you were boozing at the Furnaceman’s when you were lying face down in the snow; and thinking that Sukie was a chicken because she was white and stood on her hind legs yipping at Brenda. He talked more or less to reassure himself that he was able to:

“It’s a special kind of engraving,” he said. “Look—the figures aren’t directly representational. They’re faceless—that’s special. And their lower limbs aren’t shown in detail. It’s meant to be impressionistic. You’re supposed to see the figures dancing in a fast step, blurred as if they were before you in poor light.”

“So you’re a student?” Raybould asked. “I mean, you talk like one. You from the University? You’re a bit old, like.”

“I’m at the University.”

“Aye?”

Raybould settled himself opposite Jerry. Both men watched the engravings.

“I’m reading for a higher degree. Historical research.”

“I like a bit of history.”

“I’m doing a study of lost villages,” Jerry said, seeing Raymould’s interest. He knew he shouldn’t describe his work, since it was a dead bore to anyone but a few historians

“Lost villages? Who lost them?” Raybould was mildly amused. His small features moved closer together, nose to mouth, eyes almost meeting in merriment.

“They got built over, or the ruins sank into the ground during the past thousand years.”

“Aye?”

“If you map their distribution, you get a picture of England as it was in that time.”

“Oh, aye?” said Raybould, now uninterested. He gestured to the thick wall behind the open fireplace. “This is old, you know. A bit of the old castle before it was bombed.”

Jerry’s professional interest was immediately engaged.

“What castle?”

“This! Castle Caff, that’s this place!”

“I know what you call it. But I didn’t know it was a castle!”

No wonder Professor Bruce de Matthieu was opposed to the study he’d been working on. The fat, smarmy-voiced old bastard had been cutting just before Christmas: “All very well writing about Lost Villages, Howard, but isn’t it about time you found one or two?” And here was a bloody castle that he hadn’t known about!

“Aye, well, a sort of castle,” said Raybould. “The Nazis blew it up in the war. Bombed it, like. Blew it to buggery!”

Jerry thought he had misheard when Raybould first referred to a bombing. Now he adjusted mentally. A castle bombed!

“What did they bomb it for?”

“Here’s your sausage, bacon and eggs!” Mrs. Raybould called. “No, stay by the fire—I’ll move this table. Sam!”

Sam obliged and the scent of the food overcame Jerry. They watched him eat for a moment and then Mrs. Raybould crossed to the window.

“You couldn’t see a hand in front of you!” she called. “Telephone lines will be down. And electric. Three days, Sam?”

“About that,” Raybould said to her. He was interested in Jerry’s reaction to his story. “I don’t know why they bombed it. But they did. Only this part were left. And the cellars.”

Jerry glanced down and saw the shifting, enigmatic figures in their eternal frozen dance. A medieval castle right under his nose and he hadn’t known it existed! He might as well get a job now and forget the research. Something simple, like truck-driving. There were perks. Hard-faced Brenda, for one. Or maybe not.

“Is it all right?” asked Mrs. Raybould.

“The best I’ve ever eaten,” said Jerry truthfully. His mouth full of fried egg, he asked Raybould: “When was the castle built?”

Raybould shrugged. “I couldn’t say.”

“It can’t be medieval!”

“Oh no?” said Mrs. Raybould, She changed the subject, “They’ll never get through,” she said. “Her and Bill’s tanker. Never! We’ll have snow for three days. Be a few caught in it on the Peak.”

She didn’t seem particularly unhappy or sympathetic about the prospect. But Jerry’s belly was full, and his mind was drowsily filled with a mild curiosity about the caff. The building could be old, but not seven or eight hundred years old like the other crumbling relics of Henry Plantagenet’s troubled reign. It was too much of an effort to ask any more questions, though. He was amazingly tired.

The door swung open, causing a huge draught that brought a surly belch of flame and smoke into the room. Jerry looked round bewildered and saw the snow-covered slight figure trying to shut the door.

“Oh no,” said Mrs. Raybould.

“Well wheer else could we come!” Brenda yelled. “He’s stuck in a sodding drift miles down the Hagthorpe road. I came on. I weren’t staying to freeze out there!”

She made for the fire and stood with the snow turning to big drops of water that fell on to Jerry’s bare feet.

“She’ll have to stay,” said Sam Raybould.

Mrs. Raybould glared and collected the dirty plates. Sam Raybould’s watery eyes were on the girl’s flushed face. There was an intent, feral look on his face.

“I’ll get off to bed, if you don’t mind, Mrs. Raybould,” Jerry said. He hated confrontations, which was why Debbie had gone. She had said as much. Often. He was an intellectual, which meant that when he had to make decisions on ordinary everyday matters like rows, marriage, money, and where to live, he got confused. Debbie didn’t admire this trait. He knew it but refused to admit it to himself; when there were difficulties, he evaded them. She was a girl who took life head on. “All right, Mrs. Raybould?”

She led the way, silently loathing the lorry-girl.