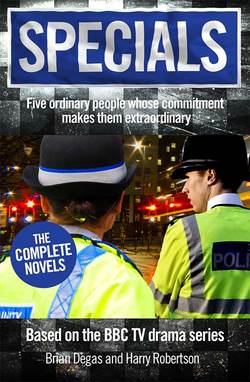

Читать книгу Specials: Based on the BBC TV Drama Series: The complete novels in one volume - Brian Degas - Страница 31

26

ОглавлениеJohn Redwood and two other Specials, another man and a woman, were clambering on board a single-decker bus to quell a burgeoning riot among twenty football supporters turned into a mob of hooligans. Brandishing beer bottles and lager cans like weapons, the heaving mass of sweaty bodies came in full battle uniform: knee-length scarves, jaunty caps and rosettes; more like a party gone wild than a mob gone berserk, each hooligan intent on showing he could laugh, shout or sing louder than the next, all showing exaggerated signs of public drunkenness.

‘Here we go, here we go, here we go,’ some of the wrestlers were singing. ‘Way the reds!’ bawled others.

Hand waving aloft to calm the situation, Redwood soon had to bring them down to protect his own midriff from two thugs brawling nearest to the door. He tried to deal with them firmly, yet quietly, and with professional courtesy.

‘All right. Can we settle down – please.’

The two thugs stopped brawling and aped his ‘please’ with raucous laughter. Another thug grabbed the woman Special and bounced her on his knee.

‘Hullo darling.’

Restoring order, Redwood tried reasoning with them. ‘Now listen, everyone. I’m sure you don’t want to miss the final.’ A few hoots and hollers came from the hecklers who were not otherwise occupied punching out somebody next to them. ‘But we have a job to do. And we need your co-operation …’

The mob gave him a sing-song reply: ‘Two, four, six, eight – why should we co-operate?’

One of the thugs snatched Redwood’s cap and hurled it like a frisbee the length of the bus. ‘A hundred and eighty!’ he boasted.

‘Come on, now,’ Redwood endeavoured to caution them. ‘Let’s be sensible …’

But the mood on board the bus was getting angrier and uglier, more disorderly by the second. Some of the mob were crowding around Redwood, surrounding him, pushing and shoving every which way.

Just when it seemed as if he might be swamped, a loud voice shouted from the back of the bus. ‘No, no, no! Hold it!’

Everyone stopped wrestling, and hostilities vanished in an instant.

The irritated voice belonged to Sergeant Crombie, who had been observing the drill from the back seat of the stationary bus at Tally-Ho, the Police Training Centre where Specials and police alike are trained. The hooligans were not supporters of the Birmingham City Football Club or the West Bromwich Albion Football Club or the Aston Villa Football Club or any other for that matter. They were simply off-duty policemen thoroughly enjoying the academic discipline of teaching new Specials the ropes.

Sergeant Crombie was a large, imposing figure whose aggressiveness seemed heightened, if possible, by the brevity of his hair. His iron stare had already singled out Redwood for a dressing-down, and the others moved away from the eye of the storm.

‘Who’s the ringleader? Him?’ Sergeant Crombie badgered Redwood, pointing to one of the pseudo-thugs. Redwood nodded, which only seemed to aggravate the tough sergeant. ‘Then collar him! Be physical! Or you’re the one to go outa here feet first. These are militant drunken louts looking for trouble. The fact that they’re off-duty policemen having a lark for your sakes is neither here nor there. You’re not here to play games. Get stuck in!’

Meanwhile, the mob surrounding them had dropped all pretence of aggression. Newspapers magically appeared, now being read by the former hooligans lolling in their seats. The woman Special had been restored to her feet. Someone tossed Redwood his cap.

Unable to ignore his education as a solicitor, however, Redwood was not entirely satisfied with the methods he was being taught, a few knotty questions still lingering in his mind.

‘Shouldn’t we first establish … uh … ascertain who’s responsible? We don’t know who’s guilty and who’s innocent.’

Sergeant Crombie did not seem overly concerned with the finer points of the law at a moment when mob violence could be imminent. ‘Ascertain? You’ve already ascertained, and you’ll get a broken bonce if you ascertain any more. Maybe I should remind you … uh …?’ He was searching for the name.

‘John Redwood.’

‘Special Constable Redwood … of what goes on in the real world.’ As Sergeant Crombie held up and counted his stubby fingers, many of the off-duty police veterans in the mob joined him in reciting the code of the west.

‘Ask ’em … tell ’em … lift ’em.’

Sergeant Crombie turned and addressed the chanting mob sweetly. ‘With your permission, gentlemen …’ Then he turned on Redwood, and the hard edge returned to his voice.

‘Now let’s get at ’em, shall we?’

That attitude, John Redwood contemplated and remembered, personified the tone and spirit that pervaded the entire training regimen prescribed for the recruited civilians who volunteered to serve as Specials. They weren’t given any special treatment, at least in the sense of mollycoddling. Yet they were given very special treatment in being afforded the same training opportunities as the PCs: what the police constables had to do, the Specials had to do.

Redwood specifically remembered the hardships of strenuous physical conditioning. Not that he was in such bad shape, but he felt all of his 42 years after several laps around the grassy perimeter of the running track. He recalled the camaraderie among these volunteers, when one of them had faltered on the track and others had given him a helping hand and encouraging words to keep going; and when the same had nearly happened to him, as he was winded and barely ploughing along under the stress: the encouragement had been for him that time. As a private, reticent, even shy man, to whom social relations and friendship had never come easily, he was getting something more out of this experience than he had expected, and it was making a deep and lasting impression on him.

Certainly he was learning skills he had never expected to acquire or need in his profession, such as how to apprehend a hostile suspect, or how to disarm a potential attacker. For a time he had been confused about such technical issues as whether his adversary’s arm should be bent up in front of or behind the body. Once he had stepped forward to face the instructor, confidently ready to spring into action and demonstrate the manoeuvre he had been shown, only to be sent flying effortlessly by the instructor.

All this in preparing for the worst, as Sergeant Crombie constantly reminded them. ‘Just because you’ve been vetted by the police, in your homes and workplaces, doesn’t mean you’re fit to undertake the duties and responsibilities of being a Special Constable,’ he had said, simultaneously warning them about and explaining the rationale for the extensive training, mental as well as physical. ‘You’ll learn what it’s like out there on the streets. And we’ll learn whether you’re competent to wear the uniform. Because you’re there to assist the police, in the full knowledge that you’re under their command, control and discipline at all times.’

Those were the kinds of ideas Redwood could respect, and wanted to hear. At least that’s what he had thought prior to one particular afternoon when he and several other Specials were in a classroom with Sergeant Crombie. On the blackboard behind him were some of the buzz-words relating to the Specials under the heading: Duties and Responsibilities. Below that were the words Code of Practice, and under that, indented to the right, each on a separate line, such phrases as Stop and Search, Obstruction, Restraint, Intimidation. Sergeant Crombie had referred to them by pointing his thumb at the blackboard over his shoulder.

‘Okay, that’s the theory,’ he had said. ‘But out on the street nobody’s gonna make any allowances because you’re a Special. The fuzz is the fuzz … even though you don’t get paid for it.’

A cheeky-faced young woman held up her hand, and Crombie had nodded for her to proceed. ‘Sir? I thought we got a quid a year?’

Although her observation tickled the Specials in the classroom, Sergeant Crombie appeared soured by her notion. ‘I’ve always thought that too generous.’ Polite laughter greeted his rejoinder.

‘But you’d better be damned sure you know why you’ve signed up to be a Special.’ At once, Redwood had never seen him more serious (though Crombie was a teacher who never even smiled). ‘And, of course, all of you sitting there think you know.’ Before they had a chance to think about it, he pounced. ‘Hands up, the ones who want to help society … clean up the streets … save the delinquent …?’

One of every pair of hands was raised high in the air, including Redwood’s.

The singular motivation for his wanting to become a Special was a painful memory. It was over a year ago, two years after his wife, Anthea, had died of a cerebral haemorrhage at the age of 36. At the time he had thought her death – so swift, so harsh – was the worst moment of his life. But then their son Simon, their only child, just 16, had been mugged. Pursued by a gang of young thugs, trapped on a pedestrian bridge over an inner city freeway, Simon had fallen from the walkway. His back had been broken, he’d suffered severe head injuries, it was touch-and-go whether he would survive. As a father called by police to identify the shattered body in the hospital bed, his first feeling had been pure hatred, a raging fury that God had singled him out again. He would have turned his back on life had his son died that night.

Confined to a wheelchair, Simon continued to suffer from the after-effects, emotional as well as physical, of the mugging, as did his father, Yet his father was an adult, capable of taking responsibility, and taking action, and he was not held back by a wheelchair. He felt that he must use his hatred, channel and focus it on something positive, something that would demonstrate – in actions rather than words – his protest against the savages, and the savagery, guilty of crippling his son. Something had to be done, he told himself. Some good had to come from this evil, some way to right the wrongs, to stand up for justice and humanity and life itself at a time when they were being threatened. And so he had joined the Specials …

‘Liars!’ shouted Sergeant Crombie, so rudely interrupting the noble thoughts of the volunteer peacekeepers and holy crusaders sitting in the classroom before him. For once in a lifetime he smiled at them, even as their smiles disappeared, and he cheerfully bullied them in a bantering tone.

‘Deep down … don’t you want to tell people what to do? Be Jack-the-Lad in a uniform? Be the Last of the Vigilantes?’

To his chagrin, Redwood realized that he, too, had a hidden agenda. Not that he really saw himself as an avenging angel, but he had often thought, in his words, ‘by being out there, I might see something, hear something,’ and often wondered what would happen if he were ever to meet face-to-face the muggers who had battered Simon. At this point, only God or a Jesuit could answer that question, but he had to admit to himself that, God help him, revenge was one of his primary motives.

A voice from the back of the classroom once again disrupted his thoughts, answering Sergeant Crombie’s nasty accusations: ‘No. I’m doing it for the money, Sarge.’

Laughter returned to the faces of the Specials, just as Crombie’s visage reverted to its normally dour form. ‘Comedians is what I get!’

Redwood had laughed along with the others, and that hadn’t been the first time. He fondly recalled a few other occasions when a wisecrack during one of the humourless training sessions, at an awkwardly inopportune moment, had nearly brought tears of laughter to his eyes. Whenever was the first time with this group, though, it had probably been the first time he had laughed aloud since Anthea was alive. Of course, he didn’t tell them about that. They didn’t know him, really.

But in a very real way, he was beginning to see that they did know each other. They were all in this together, all in the same boat, and each of them, man and woman, held an oar to pull. Despite the disbelieving scorn of Sergeant Crombie, there was something all these people cared about, in addition to each other. Yet it was the addendum that was affecting him and surprising him most. After a long, self-imposed solitude, he was, little by little, finding friends.

It wasn’t just a shared laugh or cup of coffee, all play and no work. There were serious and solemn occasions that brought them closer together as well.

Like the day of the final ceremony at the parade ground. Redwood’s own iron constitution harbored a secret weakness for pomp and circumstance (as, apparently, did Sergeant Crombie). He loved the proud music blazing forth, the synchronized rows of smart uniforms marching in precision to the pulse of the police band, filing past the highest-ranking officers, the dignitaries, and the Chief Constable, his uniform encrusted in braid …

… And finally coming to a halt in front of Sergeant Crombie. In spite of the stern demeanour the short-haired goat was trying to maintain, Redwood noticed (twice in a lifetime) a smile tugging at the corner of Crombie’s mouth.

‘Right, you lot,’ he stated, looking over the lot of them, one at a time, before going on. ‘Here endeth the lesson. Just remember … We live in iffy times.’ He was surely no good at sentimentality, which, naturally, Redwood regarded as one of Crombie’s most appealing qualities.

‘Good luck … You’ll need it.’

A loftier speech would have had less of an effect on his audience, but the Specials felt the full weight and burden of what he didn’t say. Now they understood how it felt to be police.

In the magistrate’s court as the day’s business was about to begin, lined up before the bench was a neat row of Special police constables in new, knife-creased uniforms. Facing them, in front of the bench, was Sandra Gibson, Mother of all Midland Specials. On the bench, the magistrate read the ‘swearing-in’ from a card, the Specials echoing each phrase of their pledge.

‘I do solemnly and sincerely declare and affirm …’

‘I do solemnly and sincerely declare and affirm …’

‘… that I will well and truly serve …’

‘… that I will well and truly serve …’

‘… our Sovereign Lady the Queen …’

‘… our Sovereign Lady the Queen …’

‘… in the office of Special Constable …’

Mumbling the words, John Redwood looked down at the warrant card in his hands, the magistrate’s resounding tones becoming indistinct.

‘… faithfully according to law.’

It was over as suddenly as it began. For a few moments, there was an awkward silence, a time for introspection and personal reflection perhaps. No one had really been given permission to move as yet.

The magistrate broke the tension unceremoniously. ‘Well, that’s it, ladies and gentlemen. I have a court to run.’

Officially acknowledged, authorized, warranted and sanctioned, as well as dismissed, the Specials breathed a sigh of relief, warmly congratulated one another and walked from the courtroom with shiny new haloes over their heads.

In the meantime, the magistrate leaned over the bench to detain one of the Specials. ‘Oh, Mr Redwood?’

‘Sir?’ Redwood replied, turning from his departing friends to the looming magistrate.

‘I see you’ve put yourself in the curious position of being sworn in as upholder and defender of the law on the same day.’ Redwood was about to change hats and present a case before the magistrate’s court that morning. ‘This may cause you some difficulty in the days to come. Policemen need to know the law in order to act upon it. Whereas it is a well-known fact that lawyers are the only people whose ignorance of the law goes totally unnoticed.’ His wit, alas, was apparently unappreciated.

‘However, I’d be obliged if you would slip into something more appropriate for a defending counsel … since I believe your case comes before me in thirty seconds.’