Читать книгу Walking the Corbetts Vol 2 North of the Great Glen - Brian Johnson - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

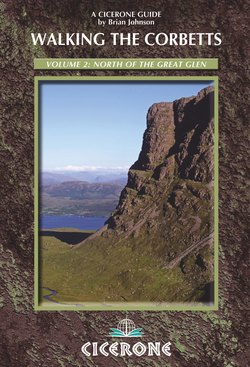

Loch Beinn Dearg, Fisherfield Forest (Route 72)

What are the Corbetts?

Scottish Peaks over 3000ft (914.4m) became known as ‘Munros’ after they were listed by Sir Hugh Munro in 1891. The Scottish Mountaineering Club (SMC) published the list and ‘Munro-bagging’ soon became a popular sport. By 2010 over 4000 people were recorded as having ‘compleated’ all the Munros, although there are many more unrecorded compleatists, too.

In 1930 John Rooke Corbett, a district valuer from Bristol, became the fourth person and first Sassenach (Englishman) to compleat the Munros, but he didn’t stop there. He went on to climb all Scotland’s hills and mountains over 2000ft (610m) and drew up a list of mountains between 2500ft (762.0m) and 3000ft (914.4m) with a drop of at least 500ft (152.4m) on all sides. When Corbett died in 1949, his sister passed his list on to the SMC, who published it alongside the Munro tables.

Corbett’s original list has been adjusted as the accuracy of maps has improved, and this has meant the addition of about 20 Corbetts and the deletion of others. Also mentioned in the route descriptions are ‘Grahams’, which are mountains between 2000 and 2499ft.

Cliffs above Allt Slochd a’ Mhogha on Sgurr Coire Choinnichean, Knoydart (Route 33)

Volume 2 covers the Corbetts north of the Great Glen, including the western seaboard and the islands of Mull, Rum, Skye and Harris. South of the Great Glen it is the Munros which attract most attention, but along the western seaboard and in the far north it is often the Corbetts or even the lowly Grahams which dominate the landscape, with isolated rocky peaks rising steeply above the sea and inland lochs, in a wilderness of heather and bog dotted with sparkling lochs and lochans. There are few Munros here, but there are spectacular Corbetts all the way from Ardgour to Cape Wrath, including those in Ardgour, Knoydart, Applecross, Torridon and Fisherfield. The far north-west provides some of the most magnificent mountain scenery in the world and it is difficult to beat the magical islands of Mull, Rum, Skye and Harris.

Is it a Corbett?

Since the lists of Munros, Corbetts or Grahams were first published there have been many revisions as more accurate OS maps have been produced. Accurate surveys, sponsored by the Munro Society, have probably settled all doubts at the boundary between Munros and Corbetts, but there are still likely to be a number of promotions or demotions between Corbett and Graham status.

The problem is highlighted in the case of a peak which appeared in the first draft of this guide but has now been excluded; Beinn Talaidh on Mull. When the OS 1:50,000 maps were first published, Beinn Talaidh was listed at 762m, the minimum height for a Corbett. Later editions listed Beinn Talaidh at 761m and it was relegated to Graham status. However, the latest OS 1:50,000 map shows Beinn Talaidh as a confusing 761(763)m. The OS seem to be doing this when the trig point is not the highest point on a summit. John Barnard and Graham Jackson in 2009, using sophisticated GPS equipment, measured the highest point as 761.7 ±0.1m and this height has now been accepted, missing the requirement for a Corbett by about 30cm (1ft). Barnard and Jackson believe the 763m may be a mistake by the OS measuring to the top of the large ‘prehistoric tumulus’ which is nearby. Incidentally, the author’s measurements gave a reading of 766m which is the same reading as he got for nearby Dun da Ghaoithe which is listed at 766m!

The OS only claim an accuracy of ±3.3m for spot heights on their maps derived from aerial photography.

Geology

An Teallach from Sail Mhor, Fisherfield Forest (Route 74)

Much of the early pioneering work in geological theory was based on investigations on the rock formations of NW Scotland. This is recognised in the UNESCO-endorsed award of Geopark status to the North-West Highlands. Geopark designation is intended to encourage geotourism, and a number of excellent visitor centres as well as roadside information boards have been developed to encourage this. This Geopark area is undoubtedly the most scenically attractive area in the UK.

The North-West Highlands contain rock formations which span over 3000 million years of earth history and include some of the oldest rocks in the world. Along the west coast, the oldest rock in the region, Lewisian gneiss, creates a landscape of low hills and scattered lochans. Rising from this gneiss landscape are huge masses of Torridonian sandstone, capped by quartzite, which form the distinctive mountains Cul Mor, Suilven, Canisp and Quinag within the Geopark as well as the mountains of Fisherfield, Torridon and Applecross further south-west.

Lewisian gneiss 2900–1100 million years old

Lewisian gneiss: Most of the Outer Hebrides and the North West Highlands Geopark have a bedrock formed from Lewisian gneiss. These are among the oldest rocks in the world, having been formed up to 3 billion years ago. About 2900–2700 million years ago north-west Scotland, together with parts of Greenland and North America, made up the ancient continent of Laurentia, which was being built up as igneous rock deep in the earth’s crust and then metamorphosed at very high temperatures. These rocks, with irregular light and dark layers, were intruded by later basaltic dykes and granite magma.

Torridonian sandstone 1000–750 million years old

Torridonian sandstone: Many of the most spectacular mountains in north-west Scotland are composed of Torridonian sandstone, a coarse-grained purplish-red sandstone. Sediments were laid down upon the gneiss by broad, shallow rivers, where the water flowed in many small channels separated by sand-bars. These sand grains and pebbles would have come from an eroding mountain range whose roots are now on the other side of the Atlantic. Deposition over 200 million years was followed by uplift and tilting downwards to the west. By 540 million years ago, erosion had formed a near-horizontal surface.

Moine schists: At the same time as the Torridonian sandstone was being laid down in the west, silt was being laid down in the east. The silt was pushed down into the earth’s crust and passed through a series of metamorphic processes, with the individual mineral grains in the schist being drawn out into flaky scales by heat and pressure, with the result that the schist splits easily into flakes or slabs. The gentler mountains in the north-east of Scotland are mainly composed of these Moine schists.

Basal quartzite 570–550 million years old

Basal quartzite, pipe rock, fucoid beds, Salterella grit and Durness limestone: Eventually, after a long period of erosion, the remains of the Torridonian sandstone in this part of Laurentia sank beneath a shallow sea. A thin sequence of sandstones, siltstones and limestones were formed in the coastal sand-bars, tidal flats and in the sea. Clean quartz sand was deposited on top of the Torridonian sandstone and a pure sandstone composed of rounded grains of quartz, cemented by further quartz between the grains was formed. This sandstone had completely different properties and is the rock we now know as basal quartzite, a white rock which is resistant to weathering and erosion. Life was developing in these waters and there is a layer of quartzite called ‘pipe rock’ where there are pipe-like burrows of fossil worms. As animals with shells developed, their fossilised remains resulted in the sediments becoming richer in ‘lime’ and in the formation of the Durness limestone.

The remarkable thing about these rocks is that the fossils are identical to those found in the Appalachian Mountains in the US but distinct from those of the same age in the rest of Britain. It is now clear that 500 million years ago Scotland, Scandinavia, Greenland and north-east America were one continent and that they were on the opposite sides of a now vanished Lapetus Ocean to the rest of Europe. This was the first conclusive evidence for continental drift.

About 430 million years ago there were intrusions of magma creating sills of crystalline rock parallel to the bedding plane, dykes cutting the bedding plane as well as plutons (irregular masses).

Between 430 and 420 million years ago a vast mountain range was being built up to the south-east as the Lapetus Ocean had closed and the ‘European plate’ was moving north-west and colliding with Laurentia. The most dramatic effect on Scotland was the pushing of a large slab of the old Moine schists over the younger rocks of north-west Scotland. This is known as the Moine Thrust.

Eventually, Scotland collided with England and fused to form one land mass before quiet conditions returned. There is no evidence in the rock record of any activity in north-west Scotland but this was a period of the build-up of sediment forming sandstone, coal, limestone, chalk and other sedimentary rocks in the remainder of Britain.

Around 60 million years ago the continent split apart, with Europe and Africa separating from America, as the Atlantic Ocean began to develop and there was volcanic activity along Scotland’s western edge.

Glacial moraine hummocks in Choire a’ Cheud-Chnoic, Torridon (Route 59)

During this time the climate cooled and by 2 million years ago the Ice Age began to affect the whole planet. Scotland would have been buried under ice and would have looked like Greenland today. It was during this time that today’s landscape developed, with massive glaciers carving out the U-shaped valleys which are such a feature of the Highlands today. Glaciers would also have carved out the corries and transported boulders long distances to scatter them over the landscape.

As in Greenland, the highest peaks would have stuck out of the ice and so wouldn’t have been smoothed by the ice, but left jagged and angular. The white cap of resistant quartzite on many of the Torridonian sandstone peaks would have helped protect them from erosion, leaving the spectacular peaks we see today. As the glaciers and icefields melted there would have been enormous flows of meltwater flowing beneath and out of the glaciers, cutting out gullies and gorges.

It wasn’t until about 11,000 years ago that the last of the glaciers finally left Scotland and peat bogs began to build up in the warmer wet conditions. Peat forms when plant material is inhibited from decaying fully by acidic and anaerobic conditions, usually in marshy areas. Peat bogs grow only at the rate of about 1mm per year.

For more information see www.scottishgeology.com or www.northwest-highlands-geopark.org.uk.

Walking the Corbetts

Walkers on the 801m subsidiary summit of Baosbheinn (Route 63)

The walks in this guide have not been designed for the peak-bagger, but primarily for the walker who wants an interesting day out on some of the less well-known but most spectacular peaks in Scotland.

Some people think the Corbetts are something to do in your declining years after you have ‘compleated’ the Munros. If you take this attitude you will miss out on many of the most spectacular and rewarding mountains in Scotland. It is true that as you get older you may appreciate the shorter walks offered by some of the Corbetts, but many of the Corbetts are very remote from road access and will still give a demanding hike. What is more, between many of the peaks listed as Munros, there is little drop, so you can often climb several in one day. By contrast, the requirement for a 500ft drop on all sides between listed Corbetts means that there are few occasions where Corbetts can be linked together. It is also surprising how few Corbetts can sensibly be combined with climbing a Munro.

This two-volume guide suggests 185 day-hikes to climb the 221 Corbetts. All the routes were walked by the author when preparing this guide. Suggestions are also made for alternative routes, but these have not always been checked by the author. This volume covers 109 Corbetts in 90 routes.

There are some areas, such as Knoydart, where the Corbetts are so remote that walking them in a day will be too much for the average walker and backpacking possibilities are considered.

When to Go

Gleann Chorainn, Bac an Eich, Strathconon (Route 49)

You will find people hiking in the Scottish Highlands throughout the year but this guidebook assumes that the Corbetts are being walked when they are free of snow. The mountains can be at their best in the winter, but weather and snow and ice conditions mean this won’t be the time for the inexperienced walker. For the experienced walker, winter in the Scottish Highlands can be magnificent. In the middle of winter there will be less than eight hours of daylight and climbing Corbetts could be a better option than climbing the Munros.

The spring in Scotland is often drier and sunnier than the summer and many consider April and May to be the best months for being in the Highlands. June, July and August are the warmest months, with the added advantage of the long daylight hours. The biggest problem with the Scottish Highlands in summer are the swarms of midges that can torment the walker, especially in the early morning and on still evenings. This is not too much of a problem for the day-hiker, but it means that this isn’t the ideal time of year for backpacking and wilderness camping.

September and October are generally relatively dry and you won’t have too much problem with midges. A combination of autumn storms and short daylight in November and December means that you are likely to be on your own in the mountains.

The Terrain

Many newcomers to Scotland underestimate the conditions they will encounter when walking in the Scottish mountains. The mountains in this guidebook may be under 1000m high, but you will usually be starting your walk from near sea level and you will spend most of the time above the tree-line, which means you will get spectacular views but will be exposed to wind, rain and sun.

Hikers from Europe and the US may be accustomed to walking on well-maintained paths and trails. Climbing the Corbetts you will frequently find the only paths are sheep or deer tracks. There are usually good tracks in the glens, maintained by the owners of the shooting estates, but higher up it is only on the most popular Corbetts that you will find well-maintained paths. Deep heather or boggy grass can make for hard walking on the approach to the mountain and steep rocky slopes protect many of the ridges. Unless there are lots of crags, the going is usually relatively easy on the ridges as a combination of wind and Arctic conditions in winter keeps the vegetation down to a minimum, although on some peaks you will have to cope with peat hags or boulderfields. Most of the peaks in the north-west are rocky and easy scrambling is required on a few of them. However, in good visibility it is possible to avoid the crags on most of the Corbetts.

Weather

Storm approaching the Bealach Bhearnais, Glen Carron (Route 53)

The main feature of the Scottish weather is its changeability and you should be prepared for anything. Sometimes it can seem as if you get all four seasons in one day. Don’t be surprised if you set out on a warm summer’s day and find it cold and windy on the summit ridge.

The north-west of Scotland has a reputation as the wettest part of Britain, with the prevailing wind bringing cloud and storms in from the Atlantic Ocean, and showery weather is common, but you may be lucky enough to get long periods of sunny weather. For instance in 2007 and 2012, when England suffered two of the wettest summers on record, north-west Scotland was largely dry and sunny and even approaching drought conditions.

There can be rain any month of the year, even in February when you may find it raining rather than snowing at 3000ft! Although there may be deep snow on the Corbetts in winter, the wind will tend blow the bulk of the snow off the peaks into the glens. Since the weather in Scotland is relatively mild for such a northerly country, the snow can melt very quickly in the glens and even on the peaks. If there is significant snow, only those with experience of winter mountaineering should attempt the steeper peaks because of the risk of cornices above the gullies and avalanche on the slopes.

It is the wind that is the most dangerous aspect of Scottish weather. If it is windy down in the glens, it could be too windy to stand up on an exposed peak. Even in summer, with the temperature well above freezing, a combination of wind and rain can lead to hypothermia unless you are properly equipped. In winter, wind can cause spindrift in the snow, creating a whiteout, even if it isn’t actually snowing. Apart from the risks of hypothermia and the difficulty of walking into a blizzard, this will also make navigation very difficult.

Mist is a feature of the weather that can cause problems for the inexperienced. If you hit a spell of cloudy weather your options can be very limited if you aren’t prepared for walking in the mist. Many of the Corbetts are rarely climbed and paths haven’t developed, so navigation in mist can be very demanding.

Access

Scotland has a system of law based as much on common law as statute law, and trespass has never been a criminal offence in Scotland. Although in the 19th century landowners were very protective of their rights of privacy, access for walkers and climbers gradually became accepted through the 20th century and free access to the mountains became enshrined in the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003. This act gives some of the best access rights in the world and the public have access to most land (including hills, woods and pastureland) for recreation, provided they act responsibly (see box).

THE SCOTTISH OUTDOOR ACCESS CODE

The Highlands are the home of Scotland’s diverse wildlife and enjoyed by the people who live and work there as well as visitors. You can exercise access rights responsibly if you:

Respect people’s privacy and peace of mind. When close to a house or garden, keep a sensible distance from the house, use a path or track if there is one and take extra care at night.

Help land managers and others to work safely and effectively. Do not hinder land-management operations and follow advice from land managers. Respect requests for reasonable limitations on when and where you can go.

Care for your environment. Do not disturb wildlife, leave the environment as you find it and follow a path or track if there is one.

Keep your dog under proper control. Do not take it through fields of calves and lambs, and dispose of dog dirt.

Deer stalking

Red deer beside Loch More

If you’re planning to walk in the Scottish hills from 1 July to 20 October, you should take reasonable steps to find out where deer stalking is taking place. As well as providing income, regular culling ensures that there is enough grazing for the herd and other animals, and that the fragile upland habitat is not damaged.

The Hillphones service provides information to enable hillwalkers and climbers to find out where red deer stalking is taking place during the stalking season, and to plan routes avoiding stalking operations. For more information go to www.snh.org.uk/hillphones.

Grouse shooting

The grouse-shooting season runs from 12 August to 10 December, with most shoots taking place during the earlier part of the season. Be alert to the possibility of shooting taking place on grouse moors and take account of advice on alternative routes. Avoid crossing land where a shoot is taking place until it is safe to do so.

Low-ground shooting

Low-ground shooting can take several forms. Pheasant and partridge shooting takes place during the autumn and winter in woods and forests, and on neighbouring land. Avoid crossing land when shooting is taking place. Avoid game bird rearing pens and keep your dog under close control or on a short lead when close to a pen.

Fishing

Access rights do not extend to fishing and the regulations are complex so you need to know the regulations before doing any fishing.

Cycling

Cyclist on the path to Glen Barisdale, Knoydart (Route 30). It’s quicker to walk!

Access rights extend to cycling. Cycling on hard surfaces, such as wide paths and tracks, causes few problems. On narrow paths, cyclists should give way to walkers and horse riders. Take care not to alarm farm animals, horses and wildlife.

If you are cycling off-path, you should avoid going onto wet, boggy or soft ground, and avoid churning up the surface. Effectively when climbing the Corbetts this means that you can use your bicycle on the estate roads and tracks to access the mountain, but the paths and off-path sections are likely to be too wet to be able to cycle without causing damage.

Wild camping

Access rights extend to wild camping. This type of camping is lightweight, done in small numbers and only for two or three nights in any one place. Avoid causing problems for local people and land managers: do not camp in enclosed fields of crops or farm animals and keep well away from buildings, roads or historic structures. Take extra care to avoid disturbing deer stalking or grouse shooting. If you wish to camp close to a house or building, seek the owner’s permission.

Leave no trace by:

taking away all your litter

removing all traces of your tent pitch and of any open fire

not causing any pollution

These rights do not extend to those using motorised transport.

Lighting fires

Wherever possible, use a stove rather than an open fire. If you do wish to light an open fire, keep it small, under control and supervised. Never light an open fire during prolonged dry periods or in areas such as forests, woods, farmland or on peaty ground, or near to buildings or in cultural heritage sites where damage can be easily caused.

Human waste

If you need to urinate, do so at least 30m from open water or rivers and streams. If you need to defecate, do so as far away as possible from buildings, from open water, rivers and streams. Bury faeces in a shallow hole and replace the turf.

Dogs and dog walking

Ptarmigan on Beinn Bhan

Access rights apply to people walking dogs provided that their dog is kept under proper control.

Your main responsibilities are:

Ground-nesting birds: During the breeding season (April–July) keep your dog on a short lead or under close control in areas such as moorland, grasslands, loch shores and the seashore to avoid disturbing birds that nest on the ground.

Farm animals: Never let your dog worry or attack farm animals. Don’t take your dog into fields with young farm animals.

Public places: Keep your dog under close control and avoid causing concern to others, especially those who fear dogs.

Dog waste: Pick up and dispose of carefully.

Fuller details can be found at www.outdooraccess-scotland.com.

Roadside camping

There is no legal right to roadside camping from a car. At one time it was common practice and this led to pollution problems in popular areas such as Glen Coe. You will find people camping beside the road, particularly in remote glens, but you should realise that you have no right to do so. You should obey any prohibition signs and you must leave if requested to do so by the landowner. Take particular care not to cause any form of pollution.

Motorhomes are a good base if you are walking in Scotland and there is rarely any difficulty finding somewhere to park. Caravans are much less flexible and should use caravan sites. Many of the single-track roads with passing places that are still common in the Highlands are not really suitable for caravans.

Roadside camping is legal under the access laws if you are walking or cycling.

Mountain Bothies

The author in Kinbreack Bothy, north of Loch Arkaig (Route 22)

The Mountain Bothies Association (MBA) is a charity that maintains about 100 bothies in Scotland. These are shelters, usually old crofts, which are unlocked and available for anyone to use. Almost all of the bothies are in remote areas and are only accessible on foot or possibly by bicycle. The MBA itself does not own any of the bothies; they are usually remote buildings that the landowner allows walkers to use.

When going to a bothy, it is important to assume that there will be no facilities. No tap, no sink, no toilets, no beds, no lights, and even if there is a fireplace, perhaps nothing to burn. Bothies may have a simple sleeping platform, but if busy you might find that the only place to sleep is on a stone floor. Carry out all your rubbish, as you would do if you were camping, and aim to leave the bothy tidier than you find it.

If you intend to make regular use of bothies you should join the MBA to contribute towards the costs of running the organisation. The MBA organises working parties to maintain and tidy up the bothies and they would welcome volunteers to help with this task. For more details on using bothies, consult the MBA’s excellent website: www.mountainbothies.org.uk.

Navigation

The 1:100,000 maps in this guide are good for planning purposes and will give you a general idea of the route, but they don’t give enough detail for accurate navigation in difficult conditions. For this reason it is essential that you carry the relevant maps.

The Ordnance Survey (OS) 1:50,000 maps, available in paper form or for GPS devices, are very good and should be all you need to follow the recommended routes. In popular areas updated OS 1:25,000 maps are available but not really necessary. Probably the best maps are the Harvey maps (mainly 1:40,000) but they don’t have full coverage of the Scottish Highlands.

The contour lines on all of these maps are remarkably accurate and should be seen as your main navigational tool. Inexperienced walkers going out in good visibility should learn to relate contours to the ground so they are better prepared if they get caught out in mist.

You should always carry a good compass (those produced for orienteering by Silva and Suunto are probably the best). In good visibility it should be sufficient to orientate the map using the compass, so that north on the map lines up with north on the ground. At present, magnetic north is near enough to grid north not to have to adjust for magnetic variation. Learn to take bearings from a map and follow them using the compass in clear conditions, before you find yourself having to navigate in mist.

The most difficult thing in navigation is knowing how far you have travelled, which can be important when navigating in mist on Scottish hills. In extreme conditions it may be necessary to pace-count to measure distance – practise this skill in good conditions, so that you are prepared.

Probably the most common navigational error is to head in the wrong direction when starting to descend so it is a good habit to always check your compass when leaving a mountain summit, even in clear conditions.

GPS

If you are experienced at using map and compass, a GPS unit is not essential for navigating the Corbetts. However, even experienced mountain navigators will find they can make navigation easier in mist and the less experienced might find that using a GPS unit allows them to navigate safely in poor visibility.

Safety

The most important thing is not how to deal with accidents, it’s how to prevent them. There are three main tips for reducing your chance of a mountain accident by about 90%:

Learn to navigate!

Learn to navigate better!

Learn to navigate even better!

The 90% figure is not a made-up statistic. Research done about 40 years ago suggested that poor navigation was a major contributory factor in about 90% of Mountain Rescue incidents in the Scottish Highlands.

Three more tips should account for the other 10% of accidents:

Make sure you have a good tread to your walking shoes or boots. Don’t wear shoes with a worn tread.

Use two walking poles – this greatly increases safety on steep grass slopes and during any difficult river crossings.

Always have waterproofs, hat and gloves in your pack, whatever the weather.

Finally, if you are intending to do any walking in winter you should take some training in walking in snow-covered mountains. There are excellent courses at Glenmore Lodge National Outdoor Training Centre (See Appendix B for details).

Areas in this Guide

1 Mull, Morvern, Sunart and Ardgour

SE face of Garbh Bheinn, towering over Loch Linnhe (Route 6)

The southern section of this guide contains some of the most magnificent, rugged, rocky mountains in Scotland, with the scenic value being enhanced by the fjord-like Loch Shiel, Loch Eil, Loch Linnhe and Loch Sunart that surround the area. Despite the fabulous scenery, this sparsely populated wilderness is rarely visited, possibly because there aren’t any Munros in the area. Ardgour (Ard Ghobhar) means ‘height of the goats’, and you can still see feral goats and it is an area where you are likely to see golden eagles.

The Isle of Mull has been included in this section because it can be convenient to access it across the Sound of Mull from Lochaline to Fishnish. The scenery on Mull is magnificent, but for many visitors it is the wildlife (including the spectacular white-tailed eagle) which attracts them to the island.

2 Glenfinnan and Rum

This section covers the peaks either side of the A830, the ‘Road to the Isles’, which links Fort William to Mallaig. The road and the spectacular railway attract a lot of tourists, but the mountains are rarely frequented, again possibly because of the absence of Munros. Centred round the tiny village of Glenfinnan at the head of Loch Shiel, included are the peaks of Moidart, the north of Ardgour and those just north of Glenfinnan. This is an area of magnificent rocky peaks which would be demanding for the inexperienced walker in bad weather.

The island of Rum has been included in Section 2 as it is accessed by ferry from Mallaig at the end of the ‘Road to the Isles’. Most of Rum is a National Nature Reserve managed by Scottish Natural Heritage. The walking throughout this rocky island is magnificent. The island is a haven for a variety of birds and animals. Rum is where the white-tailed eagle was first reintroduced to Scotland and the island is the breeding ground for about one third of the world’s population of Manx shearwater.

While you are at Mallaig you could also take a ferry to Inverie to climb the Corbetts in Knoydart which are featured in Sections 3 and 4 or a ferry to Skye to climb the two Corbetts on that island.

3 Glen Loy, Loch Arkaig, Glen Dessarry and South Knoydart

This section includes all the Corbetts that can be accessed from the minor road between Fort William and Loch Arkaig, including those that can be climbed from the roadhead at the western end the loch. There is a big contrast between the relatively gentle Corbetts in Glen Loy and overlooking Loch Arkaig and the remote, rough and rocky mountains in Glen Dessarry and Knoydart to the west of Loch Arkaig. There is neither accommodation nor campsites in this section so most visitors will be staying in or around Fort William.

Glen Dessarry is one of the access routes to the wild Knoydart peninsular. Ben Aden in Knoydart is too remote to contemplate as a day-hike from any access point and the suggestion is to access Knoydart along Glen Dessarry and stay at Sourlies Bothy on Loch Nevis to climb Ben Aden and Beinn Bhuidhe. This access could also be used, as an alternative to Kinloch Hourn, to access the remaining Corbetts in Knoydart, described in Section 4.

4 North Knoydart and Kinloch Hourn

This section includes the Corbetts that can be accessed from the small settlement of Kinloch Hourn at the eastern end of the long sea loch, Loch Hourn. Sections 3 and 4 cover an area known as na Garbh-Chriochan (the Rough Bounds), because of its harsh terrain and remoteness, and this is a good description of Knoydart which is sometimes referred to as ‘Britain’s last wilderness’. Fortunately it has good stalker’s paths to enable easy access through the rough terrain.

The distances from Loch Arkaig, Loch Hourn or from the village of Inverie mean that it isn’t really feasible to day-hike some of these Corbetts. Sgurr a’ Choire-bheithe is climbed from the remote Barisdale Bothy and other Corbetts from Inverie which can be accessed by ferry from Mallaig (see Section 2), by walking in from Sourlies Bothy (see Section 3) or by walking in from Barisdale Bothy as described in Section 4. Although Ben Aden and Beinn Bhuidhe have been included in Section 3 they could also be accessed from Barisdale or Inverie. The author recommends backpacking these peaks.

5 Glen Garry, Glen Shiel, Glen Elchaig and Loch Hourn

Sgurr Mhic Bharraich across Loch Duich from Sgurr an Airgid, Kintail (Route 41)

This section includes all the Corbetts that can be accessed from the A87 which links Invergarry to the Kyle of Lochalsh and Skye. This area is best known for the 16 Munros which line magnificent Glen Shiel and Loch Cluanie, including the Five Sisters which tower above Shiel Bridge. The Corbetts in Glen Shiel provide excellent viewpoints for these superb Munros. Also included are the remote peaks to the west of the massive Munro Carn Eige which would be best climbed on a backpacking trip and the isolated Corbetts above Arnisdale which provide magnificent views across Loch Hourn to the Knoydart Peninsula.

6 Glen Affric, Glen Cannich, Glen Strathfarrar and Strathconon

Glen Affric, Glen Cannich, Glen Strathfarrar and Strathconon are the four big glens which drain eastwards reaching the sea at Beauly Firth or Cromarty Firth, either side of the Black Isle. The long easy ridges bordering the glens provide excellent backpacking terrain and this would be the best way of climbing both the Munros and Corbetts in the area. The Munros tend to be concentrated at the head of these glens with the Corbetts further to the east. Many of the Munros are very remote but access to the Corbetts is easier for day-hikers.

7 Glen Carron, Glen Torridon and Loch Maree

Liathach from Beinn Dearg, Wester Ross (Route 58)

This section includes the spectacular peaks of Applecross and Torridon as well as the gentler peaks along Glen Carron and the isolated peaks in the Letterewe Forest to the north of Loch Maree.

Torridon is best known for the Munros Liathach and Beinn Eighe but the Corbetts in the area are every bit as dramatic, providing some of the best mountain scenery in Britain. The towering peaks are composed of Torridonian sandstone, often with a white quartzite cap, sitting on a base of Lewisian gneiss

Many of these peaks are steep and rocky and could be dangerous for the inexperienced walker in poor weather conditions.

8 Strath Garve, Fisherfield and Inverpolly

This is a rather mixed section with some rather uninteresting Corbetts along the A835 to the south-east, but some of the most dramatic mountains in Scotland to the north-west; the boundary being the line of the Moine Thrust, north-west of which the Torridonian sandstone peaks of Fisherfield and Inverpolly stand as ‘inselbergs’ above a heather wilderness scattered with numerous lochs and lochans. Also in this region is the majestic Munro An Teallach, but the finest mountains are possibly the Grahams, Suilven and Stac Pollaidh. Quite a lot of driving will be needed if you use Ullapool as a base for all these routes, but this is a region with very little accommodation and few official campsites. The peaks in the Fisherfield Forest are rather remote for a day-hike so the suggestion is to stay at Shenavall Bothy or to backpack these magnificent mountains.

9 Strathcarron and north-west Scotland

North-west Scotland provides some of the most stunning scenery in the world with Torridonian sandstone peaks rising starkly out of a wild moorland dotted with innumerable lochs and lochans finished off with views of a magnificent wild and scenic coastline. In an area with few Munros, it’s the Corbetts which dominate the landscape. There is no obvious base for this widespread section with most of the tiny population being scattered among small coastal villages whose economy is now based mainly around tourism. The magnificent scenery makes this prime backpacking terrain.

Also included in this section are the two Corbetts in Strathcarron at the head of the Dornoch Firth. These don’t fit naturally into any section but might be climbed on the drive north to the other peaks.

10 Skye and Harris

Skye is best known to walkers for the ‘Black Cuillin’ which provide some of the most dramatic and challenging mountain terrain in Scotland. Neither of the Corbetts in Skye is in the Black Cuillin, but Garbh-bheinn with some easy scrambling gives a taster of the delights of the Cuillin ridge. In complete contrast is Glamaig in the ‘Red Cuillin’, whose rounded hills are composed of granite with many long screes slopes on their flanks.

Harris (from the old Norse meaning ‘high land’) is the southern and more mountainous end of Lewis and Harris, the largest of the islands in the Outer Hebrides. Lewis has an incredibly diverse landscape, ranging from the dramatic, rocky landscape of the east coast and west coast with miles of golden sandy beaches with a backdrop of the mountains in the interior. While visiting Harris you should climb the three magnificent Grahams as well as the lone Corbett, An Cliseam.

Using this Guide

Road bridge below Sgurr nan Eugallt (Route 29)

Walking the Corbetts is divided into two volumes:

Volume 1 covers the Corbetts south of the Great Glen (which runs from Fort William to Inverness) and includes the islands of Arran and Jura.

Volume 2 covers the Corbetts north of the Great Glen and includes the islands of Mull, Rum, Skye and Harris.

Other guides number and organise the Corbetts as they appear in the SMC lists. This organisation was actually designed for the Munros and is illogical for the Corbetts. There are Corbetts in many areas where there are no Munros, and in other areas adjacent Corbetts are listed in different sections of the tables. For instance, Beinn Chuirn, Beinn Bhreac-liath and Beinn Odhar are all within 5km of Tyndrum but appear in three different sections of the SMC lists.

In this guide the Corbetts have been divided into 21 sections, 11 in Volume 1 and 10 in Volume 2. Each section could be climbed in a 1–2 week holiday. Corbetts have been arranged based on road access, so that it could be possible to climb the Corbetts in each section on a single trip.

Maps to take

The 1:100,000 maps in this guide should be sufficient to give you a feel for the route, but they are not intended for detailed navigation, particularly in bad weather. You should always carry the relevant OS Landranger (1:50,000) maps suggested for the route, either as a paper copy or loaded onto a GPS device. The Harvey maps at 1:40,000 are excellent alternatives to the OS maps, but they don’t cover all of Scotland.

Route descriptions

For each Corbett a single ascent is described. Information about distance, amount of ascent, route difficulty, time needed to complete the route, summits reached, maps required and access to the start of the route is given in the information box at the start of each description. In some cases alternative routes are also suggested, and these are marked on the route maps with a dashed orange line. The route maps are at 1:100,000 scale and based on Ordnance Survey data. Information about bases and local facilities is given in the introduction to each section.

Distances and ascents

Distances and the amount of climb are quoted to the nearest kilometre (or mile) and 10m (or 100ft) of ascent.

Timings

All timings are those measured by the author’s GPS device as he checked the routes. This device stops recording walking time whenever the walker stops, even for a few seconds, so the total time required to complete a walk will be considerably longer than that given in the guide. You should make an allowance for refreshments stops, taking photos and your own pace and fitness.

Grid references

All grid references are 10-figure references taken from the author’s GPS device, but rounded up or down to the nearest 10m. A full grid reference with the letters indicating the grid square is given in the information box at the start, but letters are only used in the grid references in the route description if the route crosses into a different grid square.

Heights

Summit cairn on Meall Dubh (Route 36)

Where spot heights are given on the route maps these figures are used in the route description. All other heights were measurements from the author’s GPS device quoted to the nearest 5m. GPS does not measure height as accurately as it does horizontal position and it is possible that some of these readings are as much as 10m out. For Corbetts (but not for other summits) the height is also given in feet; note that this is not the conversion of the metric height, but is the height given on the OS 1 inch: 1 mile map, most of which are derived from surveys in the 1950s.